Women's Transformative Experiences in the Wilderness of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio Essentials 2012

Artist Song Series Issue Track 44 When Your Heart Stops BeatingHitz Radio Issue 81 14 112 Dance With Me Hitz Radio Issue 19 12 112 Peaches & Cream Hitz Radio Issue 13 11 311 Don't Tread On Me Hitz Radio Issue 64 8 311 Love Song Hitz Radio Issue 48 5 - Happy Birthday To You Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 21 - Wedding Processional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 22 - Wedding Recessional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 23 10 Years Beautiful Hitz Radio Issue 99 6 10 Years Burnout Modern Rock RadioJul-18 10 10 Years Wasteland Hitz Radio Issue 68 4 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Radio Essential IssueSeries 44 Disc 44 4 1975, The Chocolate Modern Rock RadioDec-13 12 1975, The Girls Mainstream RadioNov-14 8 1975, The Give Yourself A Try Modern Rock RadioSep-18 20 1975, The Love It If We Made It Modern Rock RadioJan-19 16 1975, The Love Me Modern Rock RadioJan-16 10 1975, The Sex Modern Rock RadioMar-14 18 1975, The Somebody Else Modern Rock RadioOct-16 21 1975, The The City Modern Rock RadioFeb-14 12 1975, The The Sound Modern Rock RadioJun-16 10 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 4 2 Pistols She Got It Hitz Radio Issue 96 16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Radio Essential IssueSeries 23 Disc 23 3 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 16 21 Savage Feat. J. Cole a lot Mainstream RadioMay-19 11 3 Deep Can't Get Over You Hitz Radio Issue 16 6 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Hitz Radio Issue 46 6 3 Doors Down Be Like That Hitz Radio Issue 16 2 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Hitz Radio Issue 62 16 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Hitz Radio Issue 12 15 3 Doors Down Here Without You Hitz Radio Issue 41 14 3 Doors Down In The Dark Modern Rock RadioMar-16 10 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time Hitz Radio Issue 95 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Hitz Radio Issue 3 9 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Hitz Radio Issue 57 15 3 Doors Down One Light Modern Rock RadioJan-13 6 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Hitz Radio Issue 31 2 3 Doors Down Feat. -

The Shifting Literary Approach to Nature in William Bartram, Henry David

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2002 The shifting literary approach to nature in William Bartram, Henry David Thoreau, and Aldo Leopold: from untamed wilderness to conquered and disappearing land Heidi AnnMarie Wall Burns Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Burns, Heidi AnnMarie Wall, "The shifting literary approach to nature in William Bartram, Henry David Thoreau, and Aldo Leopold: from untamed wilderness to conquered and disappearing land" (2002). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16260. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16260 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The shifting literary approach to nature in William Bartram, Henry David Thoreau, and Aldo Leopold: From untamed wilderness to conquered and disappearing land by Heidi AnnMarie Wall Burns A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Literature) Program of Study Committee: Charles L. P. Silet (Major Professor) Neil Nakadate Bion Pierson Iowa State University Ames, -

Portraits of His Subjects

fall 2015 index [ new titles 5 [ backlist 64 photography 65 toiletpaper 79 fashion | lifestyle 81 contemporary art 84 alleged press 91 freedman | damiani 92 standard press | damiani 93 factory 94 music 95 urban art 96 architecture | design 98 collector's edition 100 collecting 108 [ distributors 110 [ contacts 111 2 [ new titles ] [ fall 2015 ] 3 new titles seascapes hiroshi sugimoto Water and air. These primordial substances, which make possible all life on earth, are the subject of Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Seascapes series. For over thirty years, Sugimoto has traveled the world photograph- ing its seas, producing a body of work that is an extended medita- tion on the passage of time and the natural history of the earth. Sugimoto has called photography the “fossilization of time,” and the Seascapes photographs simultaneously capture a discrete mo- ment in time but also evoke a feeling of timelessness. This volume, the second in a series of books on Sugimoto’s art, presents the com- plete series of over 200 Seascapes, some of which have never before been reproduced. All are identical in format, with the horizon line precisely bifurcating each image, though at times the sea and sky almost merge into one seamless unit. Each photograph captures a moment when the sea is placid, almost flat. Within this strict format, however, he has created a limitless array of portraits of his subjects. An essay by Munesuke Mita, Professor of Sociology at the University of Tokyo, examines contemporary art through a socio- logical lens, comparing the recent history of art with mathematical predictions of population growth. -

Examensarbete Avancerad Nivå Mannen Jagar, Kvinnan Behagar?

Examensarbete Avancerad nivå Mannen jagar, kvinnan behagar? En diskursanalys ur genusperspektiv av två musikvideor. Examensarb. nr. Författare: Lena Ohlsson Handledare: Yvonne Blomberg Examinator: Sven Hansell Ämne/huvudområde: Litteraturvetenskap Högskolan Dalarna Poäng: 15 hp 791 88 Falun Betygsdatum: 2012-01-19 Sweden Tel 023-77 80 00 Abstract Syftet med uppsatsen är att undersöka vilka underliggande mönster som styr två populärkulturella texter i form av musikvideor publicerade på webbsajten YouTube: Madonnas Like A Virgin och Lady Gagas Bad Romance, samt undersöka om dessa mönster lever vidare inom populärkulturen genom ständigt återskapande. Metoden som används är diskursanalys med genusperspektiv för att ta reda på hur maskulinitet och femininitet konstrueras i det här sammanhanget. En diakron tillika jämförande analys görs för att se om liknande diskurser styr de båda musikvideorna. I arbetet används det vidgade textbegreppet och således utgörs texterna i det här fallet av rörliga bilder, sångtexter och YouTube-kommentarer. Frågeställningarna som ligger till grund för undersökningen är följande: Vilka diskurser, sedda ur genusperspektiv, genomsyrar texterna samt hur gestaltas och förmedlas dessa? Har de båda texterna liknande underliggande mönster, trots att de producerats med 25 års mellanrum? Kan man genom intertextuella kopplingar till de analyserade verken påvisa att diskurserna hela tiden skapas och återskapas i samhället genom populärkulturella texter? Slutsatser: texterna genomsyras av fem dominerande diskurser: kvinnan som oskuld respektive hora, drömprinsen, ”en riktig karl”, mannen har makten samt den starka kvinnan. De båda texterna har liknande underliggande kulturella mönster trots de mellanliggande 25 åren. Intertextuella kopplingar till äldre verk samt moderna texter visar att diskurserna hela tiden skapas och återskapas i populärkulturen. -

Madonna - 1982 - 2009 : the Lyrics Book - 1 SOMMAIRE

Madonna - 1982 - 2009 : The Lyrics Book - www.madonnalex.net 1 SOMMAIRE P.03 P.21 P.51 P.06 P.26 P.56 P.09 P.28 P.59 P.10 P.35 P.66 P.14 P.40 P.74 P.15 P.42 P.17 P.47 Madonna - 1982 - 2009 : The Lyrics Book - www.madonnalex.net 2 ‘Cause you got the best of me Chorus: Borderline feels like I’m going to lose my mind You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline (repeat chorus again) Keep on pushing me baby Don’t you know you drive me crazy You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline Something in your eyes is makin’ such a fool of me When you hold me in your arms you love me till I just can’t see But then you let me down, when I look around, baby you just can’t be found Stop driving me away, I just wanna stay, There’s something I just got to say Just try to understand, I’ve given all I can, ‘Cause you got the best of me (chorus) Keep on pushing me baby MADONNA / Don’t you know you drive me crazy You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline THE FIRST ALBUM Look what your love has done to me 1982 Come on baby set me free You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline You cause me so much pain, I think I’m going insane What does it take to make you see? LUCKY STAR You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline written by Madonna 5:38 You must be my Lucky Star ‘Cause you shine on me wherever you are I just think of you and I start to glow BURNING UP And I need your light written by Madonna 3:45 Don’t put me off ‘cause I’m on fire And baby you know And I can’t quench my desire Don’t you know that I’m burning -

Summer 2021 Season

Beauty and the Summer 2021 Season Beast Book online | towngatetheatre.co.uk BOOKING FAST or call | 01268 205 300 See Centre Pages! Book online towngatetheatre.co.uk or by phone 01268 205 300 Keep up to date and follow us on /towngate @towngatetheatre Your guide to the Towngate Theatre Welcome back! MAIN AUDITORIUM would like to start by thanking you for your As ever, we have a whole host of amazing continued support of the Towngate Theatre over productions to treat you with over the coming the past 18 months. I know many of you have months, details of all the shows can be found in Ienjoyed our online programme of events, including this brochure. Vist our website for further upcoming Lockdown Summer School, Towngate Stories, productions from March 2022 onwards. screenings of our magical pantomimes and a MIRREN STUDIO specially commissioned filming of Dickens’ As all our wonderful panto fans know, we had no alternative but to postpone our magical pantomime, A Christmas Carol. Beauty and the Beast, from 2020/21 to 2021/22. Whilst our auditorium doors may have been closed, Thanks to the hard work of our Box Office team, the theatre certainly wasn’t. Our catering team all previous bookings were transferred safely into have produced 5,000 packed lunches to support the closest equivalent performance. The fabulous the Active Essex and Basildon Council’s School Simon Fielding and Sophie Ladds will once again Holiday Programme, we transformed the Mirren be bringing panto sparkle to our stage, and we are Studio into a Rapid Test centre, and we continued delighted to welcome back Madeleine Leslay, who to work with the NHS to deliver vaccines to over stole our hearts as feisty Alice Fitzwarren in Dick 100,000 people from our Towngate auditorium. -

Chapter Outline

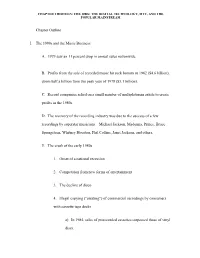

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: THE 1980s: THE DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY, MTV, AND THE POPULAR MAINSTREAM Chapter Outline I. The 1980s and the Music Business A. 1979 saw an 11 percent drop in annual sales nationwide. B. Profits from the sale of recorded music hit rock bottom in 1982 ($4.6 billion), down half a billion from the peak year of 1978 ($5.1 billion). C. Record companies relied on a small number of multiplatinum artists to create profits in the 1980s. D. The recovery of the recording industry was due to the success of a few recordings by superstar musicians—Michael Jackson, Madonna, Prince, Bruce Springsteen, Whitney Houston, Phil Collins, Janet Jackson, and others. E. The crash of the early 1980s 1. Onset of a national recession 2. Competition from new forms of entertainment 3. The decline of disco 4. Illegal copying (“pirating”) of commercial recordings by consumers with cassette tape decks a) In 1984, sales of prerecorded cassettes surpassed those of vinyl discs. CHAPTER THIRTEEN: THE 1980s: THE DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY, MTV, AND THE POPULAR MAINSTREAM F. New technologies of the 1980s 1. Digital sound recording and five-inch compact discs (CDs) 2. The first CDs went on sale in 1983, and by 1988, sales of CDs surpassed those of vinyl discs. 3. New devices for producing and manipulating sound: a) Drum machines b) Sequencers c) Samplers d) MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) G. Music Television (MTV) 1. Began broadcasting in 1981 2. Changed the way the music industry operated, rapidly becoming the preferred method for launching a new act or promoting a superstar’s latest release. -

“Like a Virgin” Musical “Road Map” Blocks Of1980sdancemusic

ga409c09.qxd 1/8/2007 8:49 AM Page 341 “Like a Virgin” Artist: Madonna From her disco beginnings to her most recent work, Madonna’s music has always been all about dance. Her intense personal style and charisma, ultra-sexual image, pioneering fashion sense, con- Music / Lyrics by Billy troversial use of religious iconography, and chameleon-like changes in personae are all part Steinberg and Tom Kelly of her unique mystique. Musically, however, this Italian-American’s roots are in African American mu- sical genres. The beat is straight out of disco, and the song structures are straight out of soul, Label: Sire, from the LP and even Motown, punctuated with the melismatic “wooo-hooos” of a gospel singer. Like a Virgin (1984) “Like a Virgin” was Madonna’s first number one single (and remained at number one on the Billboard charts for six weeks in 1984). The “Like a Virgin” video was also extremely successful, despite controversy about its sexual content, and it helped catapult her to worldwide fame. One of the most suc- cessful artists of the last three decades, Madonna has sold over 300 million records internationally. Musical Style Notes The introduction to “Like a Virgin,” with its compelling bass-synth pattern, establishes its dance beat immediately. The prevailing sonic tex- ture of disco is also evident in the instrumentation, heavy on synth and keyboards. The verses of “Like a Virgin” have a two-part structure. We hear 8 bars (measures) of music and lyrics, followed by another 8 bars that feature the same music but with different lyrics, continuing into a chorus, which is also 8 bars long. -

“Blurred Lines”: Robin Thicke and Madonna Ciccone Between Madonna and Whore

Cultural and Religious Studies, ISSN 2328-2177 January 2014, Vol. 2, No. 1, 17-28 D DAVID PUBLISHING “Blurred Lines”: Robin Thicke and Madonna Ciccone between Madonna and Whore Hartmut Heep The Pennsylvania State University, U.S.A Robin Thicke’s song “Blurred Lines” rekindled the debate about women who must choose an existence as Madonna or as whore. Biblical archetypes, such as Eve and Mary, are normative role models for women, even within secular societies. This study follows a pre-Fall Eve, who experiences shameless sexual pleasures, to a post-Fall shamed Eve, to the Virgin Mary, who is mother but virgin. Robin Thicke’s video “Blurred Lines,” and Madonna Ciccone’s various videos reclaim sexual pleasures for women outside of sin. Close readings of several visual texts will show that how meaning is redistributed among signifieds by deconstructing and redefining conventional signifiers, such as virgin and whore. Keywords : gender studies, religious studies, popular culture, feminist theory, social theory Introduction In their introductory essay "Accounting for Sexual Meanings" Sherry Ortner and Harriet Whitehead (1981) it shows how women are androcentrically defined in terms of nature, domestic, and self-interest as opposed to culture, public, and social good. The female existence arises out of serving in these subsidiary roles in which women fulfill male needs and desires. The basis for this arbitrary arrangement is the Bible. The Virgin Mary, as the archetype of mother but virgin, and Eve, in her pre-and post-Fall duality, are the accepted norms for the female existence in Christian societies. The artist Madonna Ciccione, and the video “Blurred Lines” liberate women from a blurred choice between virgin and whore. -

Healing the Wounds of Sexual Abuse Elaine A. Heath

H e a l i n g t h e Wo u n d s of Sexual Abuse Reading the Bible with Survivors Elaine A. Heath 1 We Were the Least of These FOR REFLECTION For Survivors 1. Laura’s healing began with a sermon in which she finally heard her own story. My healing began with previewing a film at my daughter’s school. How did your healing jour- ney begin? 2. Complete the following statement: When I read this chapter, a. I felt . b. I remembered . c. I hoped . d. I prayed . For Those Who Journey with Us 1. Complete the following statement: When I think about using gender- inclusive language and images for God in the teaching, preaching, and worship resources in church, a. I feel . b. I think . c. I hope . d. I pray . Recommended Activities • Watch: The Color Purple, The Tale • Create: Paint, draw, or sculpt an image to express the promise of Revelation 21:5: “See, I am making all things new.” 2 Fig Leaves FOR REFLECTION For Survivors 1. What are some of the interpretations you have heard of the story of Adam and Eve? 2. In what ways, if any, do you see the “Madonna and whore syndrome” in popular culture? 3. Complete the following statements: a. The idea that God looks at sin first from the standpoint of the sinned- against leads me to think . b. When I imagine Adam and Eve as vulnerable children rather than rebellious adults . c. My own version of wearing “fig leaves” has been to . For Those Who Journey with Us 1. -

Cob Records Porthmadog, Gwynedd, Wales

COB RECORDS PORTHMADOG, GWYNEDD, WALES. LL49 9NA Tel:01766-512170. Fax: 01766 513185 www.cobrecords.com e-mail [email protected] CD RELEASES & RE-ISSUES JANUARY 2001 – DECEMBER 2003 “OUR 8,000 BEST SELLERS” ABOUT THIS CATALOGUE This catalogue lists the most popular items we have sold over the past three years. For easier reading the three year compilation is in one A-Z artist and title formation. We have tried to avoid listing deletions, but as there are around 8,000 titles listed, it is inevitable that we may have inadvertently included some which may no longer be available. For obvious reasons, we do not actually stock all listed titles, but we can acquire them to order within days providing there are no stock problems at the manufacturers. There are obviously tens of thousands of other CDs currently available – most of them we can supply; so if what you require is not listed, you are welcome to enquire. Please read this catalogue in conjunction with our “CDs AT SPECIAL DISCOUNT PRICES” as some of the more mainstream titles may be available at cheaper prices in that feature. Please note that all items listed on this catalogue are of U.K. manufacture (apart from Imports denoted IM or IMP). Items listed on our Specials are a mix of U.K. and E.C. manufacture; we will supply you the items for the price/manufacturer you chose. ******* WHEN ORDERING FROM THIS CATALOGUE PLEASE QUOTE CAT 01/03 ******* the visitors r/m 8.50 live 7.50 ALCHEMY live at t’ fillmore east deluxe 16.50 tales of alibrarian coll’n+ DVD 20.00 10 CC voulez vous r/m 8.50 -

MDNA Tour Lyrics

MDNA Tour Lyrics Act of Contrition / Girl Gone Wild 2 Revolver 3 Gang Bang 4 Papa Don’t Preach 5 Hung Up 6 I Don’t Give A 7 Best Friend / Heartbeat (INTERLUDE) 8 Express Yourself 9 Give Me All Your Luvin’ 10 Turn Up The Radio 11 Open Your Heart / Sagarra Jo by Kalakan 12 Masterpiece 13 Justify My Love (INTERLUDE) 14 Vogue 15 Candy Shop/ Erotica 16 Human Nature 17 Like A Virgin 18 Nobody Knows Me (INTERLUDE) 19 I’m Addicted 20 I’m A Sinner / Cyberraga 21 Like A Prayer 22 Celebration 23 1 Transgression Segment Act of Contrition / Girl Gone Wild Oh my God I feel like sinnin' I am heartily sorry for having offended Thee You got me in the zone And I detest all my sins DJ play my favourite song Because I dread the loss of heaven Turn me on And the pain of hell But most of all because I love Thee I got that burnin' hot desi-i-i-ire And I want so badly to be good And no one can put out my fi-i-i-ire It's comin' right down through the wi-i-i-ire It's so hypnotic The way he pulls on me Here it comes It's like the force of gravity When I hear them 808 drums Right up under my feet It's got me singin' It's so erotic Hey-ey-ey, hey-ey-ey-ey This feeling can't be beat Like a girl gone wild It's coursing through my whole body A good girl gone wild Feel the heat I'm like hey-ey-ey-ey Like a girl gone wild I got that burnin' hot desi-i-i-ire A good girl gone wild And no one can put out my fi-i-i-ire Girls they just wanna have some fun It's comin' right down through the wi-i-i-ire Get fired up like a smokin' gun On the floor till the daylight comes Here