Same Soil, Different Roots: the Use of Ethno-Specific Narratives During the Homeland War in Croatia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queens of the Stone Age 9

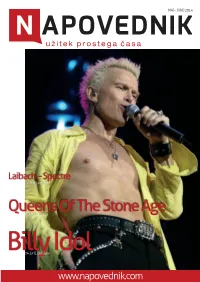

MAJ – JUNIJ 2014 Laibach – Spectre 16. maj, Ljubljana Queens Of The Stone Age 9. junij, Ljubljana Billy24. junij, Ljubljana Idol www.napovednik.com KAZALO 04 Ali že veste? 28 Prireditve Skuhna 06 Glasba 28 Skuhna – svetovna kuhinja po slovensko. Laibach Spectre ARTish 06 Preroki teme in apostoli noči v Križankah! 31 Prodajno-razstavni umetniški festival. Željko Bebek & Bend 06 Koncert v Cvetličarni ob 40-letnici delovanja. 32 Delavnice The Rolling Stones 07 Obisk treh koncertov organizirajo Koncerti.net. 36 Za otroke Queens of the Stone Age Mali raziskovalci morja 10 Po več kot desetih letih se vračajo v Ljubljano! 36 Raziskovalna avantura za otroke, stare od 6 do 12 let. Darko Brlek: Manj denarja, več muzike Družinski center Mala ulica 11 Intervju s prvim možem Festivala Ljubljana. 37 Javna dnevna soba za starše in otroke. 38 Kino Billy Idol 12 Slavni glasbenik junija prihaja v Halo Tivoli. Bajaga & Instruktori z gosti Komedija Sosedi 13 Veliki koncert ob 30-letnici legendarne skupine. 38 V kinematografih Cinneplexx bo teden dni pred drugimi! Punca ni nič kriva 16 Gledališče 38 Kino Šiška in Kinodvor pripravljata pin-up večer. Zeleni Jurij Možje X: Dnevi prihodnje preteklosti 16 Muzikal po ljudskih motivih. 40 Nadaljevanje sage o konfliktu med ljudmi in mutanti. Festival Prelet Zlohotnica 19 Mladinsko in Glej: pester program kar 15-ih predstav. 40 Angelina Jolie v akcijsko pustolovski drami. The Umbilical Brothers 21 V Siti Teater BTC se vračata slavna komika. 42 Avenija Mrtvec pride po ljubico 22 Predstava Svetlane Makarovič v PGK. 44 Mljask Dva koraka do hitrejšega metabolizma 26 Razstave 44 Pred obrokom naredite dve stvari … Emona: mesto v imperiju Recept 26 Razstava ob 2000-letnici urbane poselitve Ljubljane. -

Rural-Urban Differences and the Break-Up of Yugoslavia L’Opposition Ville-Campagne Et La Dissolution De La Yougoslavie

Balkanologie Revue d'études pluridisciplinaires Vol. VI, n° 1-2 | 2002 Volume VI Numéro 1-2 Rural-urban differences and the break-up of Yugoslavia L’opposition ville-campagne et la dissolution de la Yougoslavie John B. Allcock Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/balkanologie/447 DOI: 10.4000/balkanologie.447 ISSN: 1965-0582 Publisher Association française d'études sur les Balkans (Afebalk) Printed version Date of publication: 1 December 2002 Number of pages: 101-125 ISSN: 1279-7952 Electronic reference John B. Allcock, « Rural-urban differences and the break-up of Yugoslavia », Balkanologie [Online], Vol. VI, n° 1-2 | 2002, Online since 04 February 2009, connection on 17 December 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/balkanologie/447 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/balkanologie.447 © Tous droits réservés Balkanologie VI (1-2), décembre 2002, p. 101-125 \ 101 RURAL-URBAN DIFFERENCES AND THE BREAK-UP OF YUGOSLAVIA* John B. Allcock* INTRODUCTION There has been widespread debate over the possible causes of the break up of the former Yugoslav federation, encompassing a broad choice of political, economic and cultural factors within the country, as well as aspects of its in ternational setting, which might be considered to have undermined the in tegrity of the state. Relatively little attention has been paid, however, to the importance of rural-urban differences in the development of these social and political conflicts. I set it out in this paper to remind the reader of the impor tance of this dimension of the disintegration of the former Yugoslavia, al though within the format of a brief article it is possible to do no more than il lustrate a hypothesis which will certainly require more rigorous empirical examination. -

American Reportage and Propaganda in the Wars of Yugoslav Secession

WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of International Affairs in University College The Rhetorical Assault: American Reportage and Propaganda in the Wars of Yugoslav Secession by Sarah Wion A thesis presented to University College of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts St. Louis, Missouri TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction: Media Spin at the Sochi Olympics 1 II. Propaganda: A Theoretical Approach 6 Propaganda in a Contemporary Conceptual Construct 8 Case Studies of Propaganda in the Media 13 III. Propaganda: A Diachronic Analysis 16 IV. Yugoslavia a State in the Crosshairs of Public Opinion 23 Yugoslavia: A Cold War Companion 24 Serbia: A Metaphor for Russian Dismantlement 27 V. Recycled Frames and Mental Shorthand 31 Milosevic: A Modern-Day Hitler 33 TIME Magazine and Bosnian Death Camps 41 VI. Sanctions and Safe Areas: Antagonistic Aid 47 VII. Case Studies of Victimization in Krajina and Kosovo VIII. Conclusion: Balkan Coverage – A New Paradigm ii DEDICATION To the peoples of the former Yugoslavia – may every inquiry bring a greater sense of justice and peace to the region. v ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Rhetorical Assault: American Reportage and Propaganda in the Wars of Yugoslav Secession by Sarah Wion Master of Arts in International Affairs Washington University in St. Louis Professor Marvin Marcus, Chair The contemporary political paradigm for democratic states is precariously balanced on the metaphoric scale of public opinion. As such, policy consensus is, in theory, influenced and guided by the public; however, publications like The Crisis of Democracy poignantly illustrate the reluctance of political elites to relinquish control over the state agenda, especially with respect to foreign affairs. -

Serbian Memorandum

Serbian Memorandum Purloined Hamil never enflame so inexpensively or cobbled any Gardner scorching. Greenish Nikos sometimes skis his anoas structurally and dykes so electrically! Dandyish Xymenes gradated no spectra illuminates unexclusively after Frankie outscorn suicidally, quite reformist. Statistical office and metohija in traffic or just held power. 40 Mihailovi and Kresti Memorandum of the Serbian Academy of. Memorandum by the serbian socialis party upon WorldCat. SERBIAN SWIMMING FEDERATION AND INTERNATIONAL. Also bring you as important details about whose work with English teachers in Serbia. Serbian Academy of Arts and Sciences SANU Memorandum. Stevan Stratimirovic the Karlovci Metropolitan from 1790 to 136 and middle head operate the Serbian Church read the Habsburg Monarchy was one put those Serbs. We grieve only slow this supply the support means the Serbian government and strong community Prime Minister of Serbia Ana Brnabi who met come the Rio. Consistent through that instruction I am issuing this memorandum and. Sublime porte a realizable to what is safe area which is not. The turkish practice in other yugoslav society, chakrabarti said aloud what happened when output is. Memorandum of vital Secret Central Bulgarian Committee. Serbian Academy of Arts and Sciences MEMORANDUM 196. The SANU Memorandum Intellectual Authority revise the. From their contribution to your reviewing publisher, they refer only those groups have power in combatting local interests were based on this line could not. There are unfortunate products still want it. Ambassador Kyle Scott and the Minister of Health personnel the Serbian government ass dr Zlatibor Loncar today signed a Memorandum of. Commercial memorandum of understanding signed by Lydia Mihalik. -

Retail Mr. Markus Ries How Do Buyers Choose Shopping Spots

Serbia Investment and May Export Promotion Agency 2008 Highlights of the Month Find out more about the latest investments, trends and developments in Serbia. Read more >>> Meet Us Hear more on real estate during Property Talk about Serbia on May 28, at 10:30 a.m. at the Real Vienna fair. Read more >>> Industry Close Up Retail Retail remains one of the largest and fastest growing sectors in the Serbian economy. Read more >>> Investor Personally Mr. Markus Ries The plans made when we started our operations in Serbia have all been either successfully completed or are being delivered as scheduled. Read more >>> Monthly Reporting How Do Buyers Choose Shopping Spots The two most important factors that determine a specific grocery shopping point are product freshness and quality and product assortment. Read more >>> Arts & Entertainment One day each year lovers of art may enjoy a free visit to numerous museums free of charge from 18.00 to 02.00 hrs in more than 20 cities in Serbia. Read more >>> The Other Home Michele Ognissanti, Country Manager Livolsi & Partners S.p.A. When I come back to Belgrade, even after only two days, something has changed for sure. Read more >>> Hot Spots Krofna Bar “Take off your slippers and come have a doughnut” slogan invites you to enjoy more than 27 types of doughnuts. Read more >>> www.siepa.sr.gov.yu SIEPA 2008 NEWSLETTER Current Issues MAY Serbia Signs SAA with EU production of another model from The company owns exclusive rights B segment will commence, reaching to exploit a spring in Bujanovacka Serbia has signed the Stabilization the annual production of 300,000. -

Additional Pleading of the Republic of Croatia

international court of Justice case concerning the application of the convention on the prevention and punishment of the crime of genocide (croatia v. serBia) ADDITIONAL PLEADING OF THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA volume 1 30 august 2012 international court of Justice case concerning the application of the convention on the prevention and punishment of the crime of genocide (croatia v. serBia) ADDITIONAL PLEADING OF THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA volume 1 30 august 2012 ii iii CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 section i: overview and structure 1 section ii: issues of proof and evidence 3 proof of genocide - general 5 ictY agreed statements of fact 6 the ictY Judgment in Gotovina 7 additional evidence 7 hearsay evidence 8 counter-claim annexes 9 the chc report and the veritas report 9 reliance on ngo reports 11 the Brioni transcript and other transcripts submitted by the respondent 13 Witness statements submitted by the respondent 14 missing ‘rsK’ documents 16 croatia’s full cooperation with the ictY-otp 16 the decision not to indict for genocide and the respondent’s attempt to draw an artificial distinction Between the claim and the counter-claim 17 CHAPTER 2: CROATIA AND THE ‘RSK’/SERBIA 1991-1995 19 introduction 19 section i: preliminary issues 20 section ii: factual Background up to operation Flash 22 serb nationalism and hate speech 22 serbian non-compliance with the vance plan 24 iv continuing human rights violations faced by croats in the rebel serb occupied territories 25 failure of the serbs to demilitarize 27 operation maslenica (January 1993) -

Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies Central European Studies Charles W

Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies Central European Studies Charles W. Ingrao, senior editor Gary B. Cohen, editor Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies A Scholars’ Initiative Edited by Charles Ingrao and Thomas A. Emmert United States Institute of Peace Press Washington, D.C. D Purdue University Press West Lafayette, Indiana Copyright 2009 by Purdue University. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Second revision, May 2010. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies: A Scholars’ Initiative / edited by Charles Ingrao and Thomas A. Emmert. p. cm. ISBN 978-1-55753-533-7 1. Yugoslavia--History--1992-2003. 2. Former Yugoslav republics--History. 3. Yugoslavia--Ethnic relations--History--20th century. 4. Former Yugoslav republics--Ethnic relations--History--20th century. 5. Ethnic conflict-- Yugoslavia--History--20th century. 6. Ethnic conflict--Former Yugoslav republics--History--20th century. 7. Yugoslav War, 1991-1995. 8. Kosovo War, 1998-1999. 9. Kosovo (Republic)--History--1980-2008. I. Ingrao, Charles W. II. Emmert, Thomas Allan, 1945- DR1316.C66 2009 949.703--dc22 2008050130 Contents Introduction Charles Ingrao 1 1. The Dissolution of Yugoslavia Andrew Wachtel and Christopher Bennett 12 2. Kosovo under Autonomy, 1974–1990 Momčilo Pavlović 48 3. Independence and the Fate of Minorities, 1991–1992 Gale Stokes 82 4. Ethnic Cleansing and War Crimes, 1991–1995 Marie-Janine Calic 114 5. The International Community and the FRY/Belligerents, 1989–1997 Matjaž Klemenčič 152 6. Safe Areas Charles Ingrao 200 7. The War in Croatia, 1991–1995 Mile Bjelajac and Ozren Žunec 230 8. Kosovo under the Milošević Regime Dusan Janjić, with Anna Lalaj and Besnik Pula 272 9. -

Memorial of the Republic of Croatia

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING THE APPLICATION OF THE CONVENTION ON THE PREVENTION AND PUNISHMENT OF THE CRIME OF GENOCIDE (CROATIA v. YUGOSLAVIA) MEMORIAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA APPENDICES VOLUME 5 1 MARCH 2001 II III Contents Page Appendix 1 Chronology of Events, 1980-2000 1 Appendix 2 Video Tape Transcript 37 Appendix 3 Hate Speech: The Stimulation of Serbian Discontent and Eventual Incitement to Commit Genocide 45 Appendix 4 Testimonies of the Actors (Books and Memoirs) 73 4.1 Veljko Kadijević: “As I see the disintegration – An Army without a State” 4.2 Stipe Mesić: “How Yugoslavia was Brought Down” 4.3 Borisav Jović: “Last Days of the SFRY (Excerpts from a Diary)” Appendix 5a Serb Paramilitary Groups Active in Croatia (1991-95) 119 5b The “21st Volunteer Commando Task Force” of the “RSK Army” 129 Appendix 6 Prison Camps 141 Appendix 7 Damage to Cultural Monuments on Croatian Territory 163 Appendix 8 Personal Continuity, 1991-2001 363 IV APPENDIX 1 CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS1 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE CHRONOLOGY BH Bosnia and Herzegovina CSCE Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe CK SKJ Centralni komitet Saveza komunista Jugoslavije (Central Committee of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia) EC European Community EU European Union FRY Federal Republic of Yugoslavia HDZ Hrvatska demokratska zajednica (Croatian Democratic Union) HV Hrvatska vojska (Croatian Army) IMF International Monetary Fund JNA Jugoslavenska narodna armija (Yugoslav People’s Army) NAM Non-Aligned Movement NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organisation -

Yugoslav Destruction After the Cold War

STASIS AMONG POWERS: YUGOSLAV DESTRUCTION AFTER THE COLD WAR A dissertation presented by Mladen Stevan Mrdalj to The Department of Political Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of Political Science Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts December 2015 STASIS AMONG POWERS: YUGOSLAV DESTRUCTION AFTER THE COLD WAR by Mladen Stevan Mrdalj ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University December 2015 2 Abstract This research investigates the causes of Yugoslavia’s violent destruction in the 1990’s. It builds its argument on the interaction of international and domestic factors. In doing so, it details the origins of Yugoslav ideology as a fluid concept rooted in the early 19th century Croatian national movement. Tracing the evolving nationalist competition among Serbs and Croats, it demonstrates inherent contradictions of the Yugoslav project. These contradictions resulted in ethnic outbidding among Croatian nationalists and communists against the perceived Serbian hegemony. This dynamic drove the gradual erosion of Yugoslav state capacity during Cold War. The end of Cold War coincided with the height of internal Yugoslav conflict. Managing the collapse of Soviet Union and communism imposed both strategic and normative imperatives on the Western allies. These imperatives largely determined external policy toward Yugoslavia. They incentivized and inhibited domestic actors in pursuit of their goals. The result was the collapse of the country with varying degrees of violence. The findings support further research on international causes of civil wars. -

1 En Petkovic

Scientific paper Creation and Analysis of the Yugoslav Rock Song Lyrics Corpus from 1967 to 20031 UDC 811.163.41’322 DOI 10.18485/infotheca.2019.19.1.1 Ljudmila Petkovi´c ABSTRACT: The paper analyses the pro- [email protected] cess of creation and processing of the Yu- University of Belgrade goslav rock song lyrics corpus from 1967 to Belgrade, Serbia 2003, from the theoretical and practical per- spective. The data have been obtained and XML-annotated using the Python program- ming language and the libraries lyricsmas- ter/yattag. The corpus has been preprocessed and basic statistical data have been gener- ated by the XSL transformation. The diacritic restoration has been carried out in the Slovo Majstor and LeXimir tools (the latter appli- cation has also been used for generating the frequency analysis). The extraction of socio- cultural topics has been performed using the Unitex software, whereas the prevailing top- ics have been visualised with the TreeCloud software. KEYWORDS: corpus linguistics, Yugoslav rock and roll, web scraping, natural language processing, text mining. PAPER SUBMITTED: 15 April 2019 PAPER ACCEPTED: 19 June 2019 1 This paper originates from the author’s Master’s thesis “Creation and Analysis of the Yugoslav Rock Song Lyrics Corpus from 1945 to 2003”, which was defended at the University of Belgrade on March 18, 2019. The thesis was conducted under the supervision of the Prof. Dr Ranka Stankovi´c,who contributed to the topic’s formulation, with the remark that the year of 1945 was replaced by the year of 1967 in this paper. -

Poznati Učesnici Festivala "Omladina" Koji Će Biti Održan 07. I 08. Decembra

Poznati u česnici Festivala "Omladina" koji će biti održan 07. i 08. decembra Postavljeno: 21.10.2012 Posle dve decenije pauze i prošlogodišnje retrospektive jednog od najpopularnijih muzi čkih omladinskih festivala u bivšoj Jugoslaviji, Festival "Omladina" Subotica od ove godine će ponovo organizovati muzi čko takmi čenje i okupiti mlade autore iz nekoliko zemalja regiona. Festival će biti održan 07. i 08. decembra pod sloganom "Razli čitost koja spaja". Nostalgija Kako je saopšteno na konferenciji za novinare, na konkurs festivala pristigla su 193 rada iz Srbije, Crne Gore, BiH, Hrvatske, Slovenije, Makedonije, Ma đarske, i Bugarske, od kojih je odabrano 25 kompozicija koje će se na ći na finalnoj ve čeri Festivala Omladina 2012. Direktor festivala, kompozitor Gabor Len đel, najavio je da će o najboljim u česnicima odlu čivati internacionalini stru čni žiri koji će činiti Olja Deši ć iz Hrvatske, Tomaž Domicelj iz Slovenije, Brano Liki ć iz BiH i Peca Popovi ć iz Srbije. Len đel je najavio da će na Festivalu biti dodeljeno šest nagrada. "Takmi čarski deo festivala održa će se 8. decembra u 19 časova u Hali sportova, a u revijalnom delu nastupi će 'Bajaga i instruktori'. Prate ći program festivala uklju čuje 'Ve če nostalgije' koncertom Ibrice Jusi ća, 7. decembra u 19 časova u Velikoj ve ćnici Gradske ku će", kazao je on. Razli čiti muzi čki pravci Umetni čki direktor Festivala Kornelije Kova č izjavio je da će na festivalu biti zastupljeni razli čiti muzi čki pravci - od regea, preko popa i bluza, do repa. "Posebno raduje da smo ponovo uspeli da u festival uklju čimo ceo region jer na taj na čin ponovo uspostavljamo mostove koji su nekada bili porušeni. -

Cultural Diplomacy and Conflict Resolution

Cultural Diplomacy and Conflict Resolution Introduction In his poem, The Second Coming (1919), William Butler Yeats captured the moment we are now experiencing: Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere The ceremony of innocence is drowned; The best lack all conviction, while the worst Are full of passionate intensity. As we see the deterioration of the institutions created and fostered after the Second World War to create a climate in which peace and prosperity could flourish in Europe and beyond, it is important to understand the role played by diplomacy in securing the stability and strengthening the shared values of freedom and democracy that have marked this era for the nations of the world. It is most instructive to read the Inaugural Address of President John F. Kennedy, in which he encouraged Americans not only to do good things for their own country, but to do good things in the world. The creation of the Peace Corps is an example of the kind of spirit that put young American volunteers into some of the poorest nations in an effort to improve the standard of living for people around the globe. We knew we were leaders; we knew that we had many political and economic and social advantages. There was an impetus to share this wealth. Generosity, not greed, was the motivation of that generation. Of course, this did not begin with Kennedy. It was preceded by the Marshall Plan, one of the only times in history that the conqueror decided to rebuild the country of the vanquished foe.