Skirtboarder Net-A-Narratives: a Socio-Cultural Analysis of a Women's Skateboarding Blog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

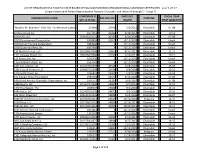

(BOE) Organizational Clearance Certificates- As of 1-27-17

LIST OF ORGANIZATIONS HOLDING STATE BOARD OF EQUALIZATION (BOE) ORGANIZATIONAL CLEARANCE CERTIFICATES - as of 1-27-17 (Organizations with Names Beginning with Numeric Characters and Letters A through C - Group 1) CORPORATE D DATE OCC FISCAL YEAR ORGANIZATION NAME BOE OCC NO. PURPOSE OR LLC ID NO. ISSUED FIRST QUALIFIED "Stephen M. Brammer" Post 705 The American Legion 233960 22442 3/2/2012 Charitable 07-08 10 Acre Ranch,Inc. 1977055 22209 4/30/2012 Charitable 10-11 1010 CAV, LLC 200615210122 20333 6/30/2008 Charitable 07-08 1010 Development Corporation 1800904 16010 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl 1010 Senior Housing Corporation 1854046 3 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl 1010 South Van Ness, Inc. 1897980 4 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl 110 North D Street, LLC 201034810048 22857 9/15/2011 Charitable 11-12 1111 Chapala Street, LLC 200916810080 22240 2/24/2011 Charitable 10-11 112 Alves Lane, Inc. 1895430 5 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl 1150 Webster Street, Inc. 1967344 6 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl 11th and Jackson, LLC 201107610196 26318 12/8/2016 Charitable 15-16 12010 South Vermont LLC 200902710209 21434 9/9/2009 Charitable 10-11 1210 Scott Street, Inc. 2566810 19065 4/5/2006 Charitable 03-04 131 Steuart Street Foundation 2759782 20377 6/13/2008 Charitable 07-08 1420 Third Avenue Charitable Organization, Inc. 1950751 19787 10/3/2007 Charitable 07-08 1440 DevCo, LLC 201407210249 24869 9/1/2016 Charitable 15-16 1440 Foundation, The 2009237 24868 9/1/2016 Charitable 14-15 1440 OpCo, LLC 201405510392 24870 9/1/2016 Charitable 15-16 145 Ninth Street LLC -

Brand Management Strategy for Korean Professional Football Teams

Brand Management Strategy for Korean Professional Football Teams : A Model for Understanding the Relationships between Team Brand Identity, Fans’ Identification with Football Teams, and Team Brand Loyalty A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ja Joon Koo School of Engineering and Design Brunel University March 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank many individuals without whom the completion of this dissertation would not have been possible. In particular, I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my supervisor Dr. Ray Holland who has supported my research with valuable advice and assistance. I also wish to extend express thankfulness for my college Gwang Jin Na. His valuable comments were much appreciated to conduct LISREL. In addition, my special thanks go to all respondents who completed my survey. Finally, but definitely not least, I would like to give my special appreciation to my family. To my parent, thank you for their endless love and support. I thank my brother, Ja Eun for his patience and encouragement throughout this process. Especially, my lovely wife, Mee Sun and son, Bon Ho born during my project have encouraged me to complete this dissertation not to give up. I am eternally grateful to all of you. i ABSTRACT This research recommends a new approach to brand strategy for Korean professional football teams, focusing on the relationships between team brand identity as the basic element of sports team branding, team brand loyalty as the most desirable goal, and identification between fans and teams as the mediator between identity and loyalty. Nowadays, professional football teams are no longer merely sporting organisations, but organisational brands with multi-million pound revenues. -

Chico State in the Ncaa Championship Tournament

2008 WOMEN’S SOCCER SCHEDULE Day Date Opponent Time Place Fri. Aug. 15 Sacramento State (exhibition) 7:00 CHICO Sun. Aug. 17 UC Davis (exhibition) 11:00 CHICO Thur. Aug. 28 Notre Dame de Namur 7:00 CHICO Sat. Aug. 30 NDNU vs. NW Nazarene (neutral site) 4:30 CHICO Sat. Aug. 30 Academy of Art University 7:00 CHICO Mon. Sep. 1 Northwest Nazarene 11:00 CHICO Thur. Sep. 4 St. Martin's University 1:00 Olympia, WA Sat. Sep. 6 Seattle Pacific University 12:00 Seattle, WA Wed. Sep. 10 Western Washington University 7:00 CHICO Sun. Sep. 14 Humboldt State* 11:30 CHICO Fri. Sep. 19 Cal Poly Pomona* 4:30 CHICO Sun. Sep. 21 Cal State San Bernardino* 11:30 CHICO Fri. Sep. 26 San Francisco State* 4:00 San Francisco Sun. Sep. 28 CSU Monterey Bay 11:30 Seaside Wed. Oct. 1 Cal State Stanislaus* 7:00 CHICO Fri. Oct. 3 Cal State L.A.* 4:00 Los Angeles Fri. Oct. 10 Cal State Dominguez Hills* 7:00 CHICO Sun. Oct. 12 UC San Diego* 11:30 CHICO Fri. Oct. 17 CSU Monterey Bay* 4:30 CHICO Sun. Oct. 19 San Francisco State* 11:30 CHICO Sun. Oct. 26 Cal State Stanislaus* 11:30 Turlock Fri. Oct. 31 Humboldt State* 7:00 Arcata Sun. Nov. 2 Sonoma State* 2:00 Rohnert Park Fri.-Sun. Nov. 7-9 CCAA Championship Tournament TBA Thur.-Sun. Nov. 13-16 NCAA Far West Regional TBA Fri.-Sun. Nov. 21-23 Far West Championship & Quarterfinals TBA Fri.-Sun. Dec. 5-7 NCAA Final Four Tampa, FL *CCAA match Cover Photography by Skip Reager 2008 CHICO STATE WOMEN’S SOCCER WILDCATS SOCCER WHAT'S INSIDE.. -

05FB Guide P187-208.Pmd

CAL TRADITIONS erhaps nowhere else in America is the color and pageantry of college football better captured on autumn Saturdays than at the University of CALIFORNIA VICTORY CANNON California and Memorial Stadium, which was judged to have the best P The California Victory Cannon was presented to the Rally Committee in view of any college stadium in the country by Sports Illustrated. The rich time for the 1963 Big Game by the class of 1964. It is shot off at the history of the Golden Bears on the gridiron has borne some of the most beginning of each game, after each score and after each Cal victory. Only colorful and time-honored traditions in the sport today. once, against Pacific on Sept. 7, 1991, did the Bears score too many times, racking up 12 touchdowns before the cannon ran out of ammunition. The BLUE AND GOLD cannon, which was originally kept on the sidelines, has been mounted on Tightwad Hill above Memorial Stadium since 1971. Official colors of the University of California were established at Berkeley in 1868. The colors were chosen by the University’s founders, who were mostly Yale men who had come West. They selected gold as a color repre- TIGHTWAD HILL senting the “Golden State” of California. The blue was selected from Yale For decades, enterprising blue. Cal teams have donned the blue and gold since the beginning of intercol- Golden Bear fans have hiked legiate athletic competition in 1882. to Tightwad Hill high above the northeast corner of Me- GOLDEN BEARS morial Stadium. Not only does the perch provide a free In 1895, the University of California track & field team was the dominant look at the action on the power on the West Coast and decided to challenge several of the top teams in field, but it also offers a spec- the Midwest and East on an eight-meet tour that is now credited by many tacular view of San Francisco historians as putting Cal athletics onto the national scene. -

Numbers Game Game, Which Breaks Don Maynard’S NFL Record

This Day In Sports 1995 — Jerry Rice has 181 yards receiving in San Francisco’s 27-24 loss to Detroit. It’s his 51st 100-yard Numbers Game game, which breaks Don Maynard’s NFL record. C4 Antelope Valley Press, Wednesday, September 25, 2019 Morning rush Pac-12: Cal, yes Cal, is lone undefeated Valley Press news services By ANNE M. PETERSON solid, especially on defense, with Silfverberg, Gibson lead Ducks past Associated Press STILL one of the best secondaries in the Sharks, 4-1 Following California’s victory PERFECT league. And Weaver is a force. ANAHEIM — Jakob Silfverberg had a goal over Mississippi, coach Justin California Weaver had a career-high 22 tackles against Ole Miss, break- and an assist, John Gibson made 31 saves, and the Wilcox said: “We find a way to quarterback ing his high of 18 set in the game Ducks beat the San Jose Sharks 4-1. make it interesting.” Chase Garbers Brendan Guhle also had a goal and an assist, at Washington. He’s had at least Yes, they certainly do. (7) releases a and Andreas Martinen and Derek Grant also The Golden Bears not only 10 tackles in 11 straight games. scored for the Ducks. Jonny Brodzinski scored for pass during the For the second time in the past emerged with a dramatic 28-20 first half against San Jose, and Aaron Dell made 33 saves. victory over Ole Miss last week- three weeks he was named the Mississippi end but the win also left them as Pac-12’s Defensive Player of the in Oxford, Mystics top Aces 94-90, advance to the lone undefeated team in the Week. -

Musical Segregation in American College Football

Journal of the Society for American Music (2020), Volume 14, Number 3, pp. 337–363 © The Society for American Music 2020 doi:10.1017/S175219632000022X “This Is Ghetto Row”: Musical Segregation in American College Football JOHN MICHAEL MCCLUSKEY Abstract A historical overview of college football’s participants exemplifies the diversification of main- stream American culture from the late nineteenth century to the twenty-first. The same can- not be said for the sport’s audience, which remains largely white American. Gerald Gems maintains that football culture reinforces the construction of American identity as “an aggres- sive, commercial, white, Protestant, male society.” Ken McLeod echoes this perspective in his description of college football’s musical soundscape, “white-dominated hard rock, heavy metal, and country music—in addition to marching bands.” This article examines musical segregation in college football, drawing from case studies and interviews conducted in 2013 with university music coordinators from the five largest collegiate athletic conferences in the United States. These case studies reveal several trends in which music is used as a tool to manipulate and divide college football fans and players along racial lines, including special sections for music associated with blackness, musical selections targeted at recruits, and the continued position of the marching band—a European military ensemble—as the musical representative of the sport. These areas reinforce college football culture as a bastion of white strength despite the diversity among player demographics. College football is one of the many public stages on which mainstream American culture diversified between the late nineteenth and the twenty-first centuries. -

Radio/TV Roster

Radio/TV Roster 0 Alex Padilla 1 Earl Edwards Jr. 2 Javan Torre 3 Michael Amick 4 Grady Howe 5 Aaron Simmons Gk • 6-1/160 • RSo. Gk • 6-3/205 • RJr. D • 6-2/175 • So. D • 6-0/165 • Fr. Mf/D • 5-10/155 • So. D • 6-0/166 • Jr. 6 Jordan Vale 7 Felix Vobejda 8 Victor Chavez 9 Willie Raygoza 10 Leo Stolz 11 Victor Munoz Mf • 5-11/169 • So. F • 5-8/145 • Fr. F • 5-11/170 • Sr. Mf • 5-8/140 • Fr. Mf • 5-11/170 • Jr. D • 5-7/160 • Sr. 12 Gage Zerboni 13 Nico Gonzalez 14 Nathan Smith 15 Cole Nagy 16 Ryan Lee 17 Nati Schnitman F/Mf • 5-10/160 • Fr. Mf • 5-9/137 • So. D • 5-10/150 • Fr. Mf /D • 5-8/160 • RFr. Mf • 6-1/175 • RSr. Mf/D • 6-0/165 • RSo. 18 Brian Iloski 19 Jake Tenzer 20 Andrew Tusaazemajja 21 Juan Cervantes 22 Munny Manak 23 Kevin De La Torre Mf • 5-7/140 • Fr. Gk • 6-0/170 • RSo. F • 5-7/165 • RJr. Gk • 5-11/180 • So. F • 6-0/163 • RFr. F • 5-9/150 • Fr. 24 Reed Williams 25 Max Estrada 26 Michael Griswold 27 Joe Sofi a 28 Gregory Antognoli 29 Patrick Matchett F • 6-2/175 • Sr. F • 5-8/150 • Sr. D/Mf • 6-3/185 • Fr. D • 6-2/180 • Sr. F • 6-0/170 • Fr. D • 6-1/180 • Sr. 30 Edgar Contreras Head Coach Assistant Coach Assistant Coach Assistant Coach D • 6-0/185 • Jr. -

UCLA's National Team Connection

UCLA’s National Team Connection Sasha Victorine were key contributors on the U.S. team that fi nished a best-ever fourth at the 2000 UCLA World Cup Players 2010 ............ Carlos Bocanegra Games in Sydney. In 1996, former Bruins Hejduk .....................Jonathan Bornstein and Chris Snitko competed for the United States ...........................Benny Feilhaber in Atlanta, and the 1992 Olympic team included six 2006 ............ Carlos Bocanegra former Bruins — Friedel, Henderson, Jones, Lapper, ..............................Jimmy Conrad Moore and Zak Ibsen — on its roster, the most from .................................. Eddie Lewis any collegiate institution. Other UCLA Olympians ...................Frankie Hejduk (inj.) 2002 .......................Brad Friedel include Caligiuri, Krumpe and Vanole (1988) and Jeff ............................Frankie Hejduk Hooker (1984). ....................................Cobi Jones Several Bruins were instrumental to the United .................................. Eddie Lewis ........................... Joe-Max Moore States’ gold medal win at the 1991 Pan American 1998 .......................Brad Friedel Games. Friedel tended goal for the U.S., while Moore ............................Frankie Hejduk nailed the game-winning goal in overtime in the gold- ....................................Cobi Jones medal match against Mexico. Jones scored one goal ........................... Joe-Max Moore and an assist against Canada. A Bruin-dominated U.S. 1994 .....................Paul Caligiuri team won a bronze -

FORUM Sports Digest Describe Life Watch Race for Lt

Community AAUW speakers FORUM sports digest describe life Watch race for Lt. Gov. .........Page A-6 in Japan ...................................Page A-4 ...........Page A-3 INSIDE Mendocino County’s World briefly The Ukiah local newspaper ..........Page 2 Tomorrow: Partly sunny 7 58551 69301 0 FRIDAY Feb. 24, 2006 50 cents tax included DAILY JOURNAL ukiahdailyjournal.com 40 pages, Volume 147 Number 321 email: [email protected] Chamber drops Fourth of July celebration; can’t afford it By K.C. MEADOWS play will be upwards of $35,000 this first three main sponsors they were which has done the fireworks show to make this happen,” she said. “I am The Daily Journal year. That includes $20,000 for the unable to put it into their budget this for the Chamber in Ukiah in the past so willing to help somebody else do The Ukiah Chamber of fireworks alone, $5,000 for the state year,” Blower explained. and which says it’s raising its fees by it, I feel bad that this may not hap- Commerce says it will not be able to Fire Marshal’s sign off (because the In 2005 the chamber collected 30 percent in 2006. pen. I was born and raised here, I afford to put on the Fourth of July event is held at the fairgrounds, state $13,000 in admissions at what many Blower said she’s just sick about remember parking on State Street officials are required to give the show and fireworks this summer. considered a steep ticket cost of $10 the Chamber having to make the and watching the fireworks.” Chamber CEO Cherie Blower OK); and thousands more in insur- for adults and $6 for children. -

President's Message New Website Launches

PRESIDENT’SUPDATE COVERING JUNE 2014 IN THIS ISSUE President’s Message While the weather gets warmer and many are taking a much-needed break, President’s Message Rio Hondo College is still busy this summer as we offer summer session classes and gear up for the fall semester. Summer classes kicked off June by offering five different sessions: two five- New Website Launches weeks, one six-week, one eight-week and one 10-week. The last summer session ends Aug. 15. There are nearly 500 courses from which to choose this summer, including Counseling 105: Orientation and Education, which is designed to assist Board Update students in creating their own educational goals, which is perfect for first-time college students. Another exciting summertime development at Rio Hondo College is the launch Nursing Students Volunteer at of the College's new website. Designed to be aesthetically pleasing and more Health Screening organized, the user-friendly site allows visitors to easily navigate classes, calendars, financial aid information, announcements and more. Teresa Dreyfuss Officials at the College have also been hard at work outlining the College’s goals and open-access to those in Online, Evening Classes Offered the College district, which includes: nine cities, in whole or part, four distinct unincorporated communities, During Summer Session and a portion of one other unincorporated community of Los Angeles County. The cities include El Monte, South El Monte, Pico Rivera, Santa Fe Springs, and Whittier. The District also encompasses portions of Norwalk, Downey, La Mirada, and City of Industry. The unincorporated Students Stand Out at communities within our District include Los Nietos, East Whittier, South Whittier, West Whittier, and a Soroptomist Awards portion of Avocado Heights. -

2007 Golden Bear Soccer

CALIFORNIA Golden Bears 2007 GOLDEN BEAR SOCCER BEAR FACTS TABLE OF Location: Berkeley, CA Enrollment: 33,000 CONTENTS Founded: 1868 Team Roster ................................. IFC Nickname: Golden Bears 2007 Season Outlook ....................... 2 Colors: Blue (282) and Gold (116) Head Coach Kevin Grimes ............... 3 Conference: Pacific-10 Stadium (cap.): Edwards Stadium (22,000) Assistant Coaches ........................... 4 Field (surface): Goldman Field (natural grass) Endowments ..................................... 5 Director of Athletics: Sandy Barbour 2007 Athlete Profiles ................... 6-10 Deputy Director of Athletics/SWA: Teresa Kuehn Gould 2006 Season in Review .................. 11 Head Coach (Alma Mater): Kevin Grimes (SMU, 1990) 2006 Results & Stats ...................... 12 Record at Cal/Career: 81-51-13/same 2006 Pac-10 Standings Assistant Coach: Pieter Lehrer (UCLA, 1990) Goalkeeper Coach: Henry Foulk (California, 1984) and Awards ..................................... 13 Soccer Office Phone: (510) 642-5916 2007 Opponents ............................. 14 Soccer Office Fax: (510) 643-2536 Series Records ............................... 15 Coach Grimes’ Email: [email protected] All-Time Results ........................ 16-17 2006 Overall Record: 13-6-1 All-Time Records ............................ 18 Pac-10 Record/Finish: 7-3-0/1st All-Time Awards and Honors.......... 19 Last NCAA Appearance: 2006 – Round of 16 Lettermen Returning/Lost: 17/6 Cal Players in the Pros ............. 20-21 Starters Returning/Lost: -

Dev K. Mishra, MD Curriculum Vitae

Dev K. Mishra, MD Curriculum Vitae Citizenship: USA Professional: 1. Clinical Assistant Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery & Sports Medicine, Stanford University September 2013 – Present Team Physician staff, Stanford University Team Physician staff, United States Soccer Federation Team Physician, International Champions Cup international soccer tournament Orthopedic Consultant: Sacred Heart Prep School, Crystal Springs Uplands School—all sports Former Team Physician, Cal Berkeley Intercollegiate Athletics Teams—all sports Former Team Physician, Oakland Athletics major league baseball 2. President, Sideline Sports Doc, LLC January 2010 – Present Sideline Sports Doc created an injury assessment algorithm and provides on-field injury management tools and risk management guidance for youth sports parents, coaches, clubs, leagues, and insurers. 3. Medical Director, Apeiron Life June 2018 – Present Apeiron Life provides comprehensive nutrition, fitness, and lifestyle guidance to improve healthspan. 4. Consultant, Stryker Endoscopy January 2014 – Present Design and product validation for endoscopic cameras and associated endoscopic tools. 5. Venture Capital and Medical Device Consulting January 2000 – Present Assist medical device and medical service focused VCs in diligence, deal sourcing. To date, I have advised my clients on more than 100 companies in a wide variety of medical specialties. I have also served as chief medical officer to seven companies that have had successful exits. Prior Medical Practice: 1. Burlingame Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine Associates January 2005 – August 2013 Arthroscopy, sports medicine 2. Saint Francis Center for Sports Medicine, San Francisco and Walnut Creek, California April 2000 – January 2011 Arthroscopy, sports medicine 3. Webster Orthopaedic Medical Group, San Ramon, California March 2003 – August 2004 4. Palo Alto Medical Foundation Sports Medicine, Palo Alto, California January 2001 – February 2003 5.