Musical Segregation in American College Football

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football Cover Single FINAL.Jpg

TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION • 2-7 HISTORY • 95-123 President Morton Schapiro ...................2 Yearly Summary ....................................96 Year-By-Year Results ................... 97-102 Vice President for Letterwinners ................................103-110 Athletics & Recreation Wildcat Legend Otto Graham ............111 Jim Phillips ............................................. 3-7 All-Americans/All-Big Ten ...........112-113 Academic All-Big Ten ................... 114-116 NU Most Valuable Players ..................115 Northwestern Team Awards.............. 117 College Football Hall of Fame ..........118 All-Star Game Participants ................119 Wildcats in the Pros .....................120-121 Wildcat Professional Draftees ....... 122-123 2015 TEAM BACKGROUND RECORD BOOK • 124-145 INFORMATION • 8-17 Total Oense .........................................126 Season Notes .....................................10-11 Rushing ........................................... 127-128 Personnel Breakdown .....................12-13 Passing .............................................129-131 Rosters .................................................14-15 Receiving ........................................ 132-133 2015 Quick Facts/Schedule ................16 All-Purpose Yards ........................133-134 All-Time Series Records ........................17 Punt Returns .........................................135 Kicko Returns .....................................136 Punting .................................................. -

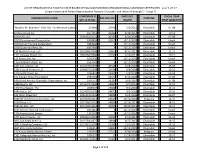

(BOE) Organizational Clearance Certificates- As of 1-27-17

LIST OF ORGANIZATIONS HOLDING STATE BOARD OF EQUALIZATION (BOE) ORGANIZATIONAL CLEARANCE CERTIFICATES - as of 1-27-17 (Organizations with Names Beginning with Numeric Characters and Letters A through C - Group 1) CORPORATE D DATE OCC FISCAL YEAR ORGANIZATION NAME BOE OCC NO. PURPOSE OR LLC ID NO. ISSUED FIRST QUALIFIED "Stephen M. Brammer" Post 705 The American Legion 233960 22442 3/2/2012 Charitable 07-08 10 Acre Ranch,Inc. 1977055 22209 4/30/2012 Charitable 10-11 1010 CAV, LLC 200615210122 20333 6/30/2008 Charitable 07-08 1010 Development Corporation 1800904 16010 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl 1010 Senior Housing Corporation 1854046 3 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl 1010 South Van Ness, Inc. 1897980 4 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl 110 North D Street, LLC 201034810048 22857 9/15/2011 Charitable 11-12 1111 Chapala Street, LLC 200916810080 22240 2/24/2011 Charitable 10-11 112 Alves Lane, Inc. 1895430 5 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl 1150 Webster Street, Inc. 1967344 6 12/11/2003 Charitable Unavl 11th and Jackson, LLC 201107610196 26318 12/8/2016 Charitable 15-16 12010 South Vermont LLC 200902710209 21434 9/9/2009 Charitable 10-11 1210 Scott Street, Inc. 2566810 19065 4/5/2006 Charitable 03-04 131 Steuart Street Foundation 2759782 20377 6/13/2008 Charitable 07-08 1420 Third Avenue Charitable Organization, Inc. 1950751 19787 10/3/2007 Charitable 07-08 1440 DevCo, LLC 201407210249 24869 9/1/2016 Charitable 15-16 1440 Foundation, The 2009237 24868 9/1/2016 Charitable 14-15 1440 OpCo, LLC 201405510392 24870 9/1/2016 Charitable 15-16 145 Ninth Street LLC -

Broadcasting the Bedroom: Intimate Musical Practices and Collapsing Contexts on Youtube

Broadcasting the bedroom: Intimate musical practices and collapsing contexts on YouTube Maarten Michielse In an era of social media and online participation, uploading a personal video to a platform such as YouTube appears to be an easy and natural activity for large groups of users.i Various discourses on online narcissism and exhibitionism (Balance, 2012; Keen, 2007, 2012; Twenge and Campbell, 2010) give the impression that current generations have become extremely comfortable (perhaps even too comfortable) with the online possibilities of self-exposure and self-representation (Mallan, 2009). As I will argue in this chapter, however, this is largely a misrepresentation of the everyday struggles and experiences of online participants. For many, posting a video on YouTube is a rather ambivalent activity: joyful and fun at times, but also scary and accompanied by feelings of insecurity, especially when the content is relatively delicate. This shows itself perhaps most clearly in a particular genre of online videos: the ‘musical bedroom performance’. On YouTube, this genre has become a popular trope in the last couple of years. In these videos, a person sings and/or plays a musical instrument in front of the camera from the private sphere of the home. As Jean Burgess (2008) argues, the musical bedroom performance ‘draws on the long traditions of vernacular creativity articulated to ‘privatised’ media use’ (p. 107).ii Historically, the bedroom has functioned as a crucial site for cultural expression and experimentation. This is especially true for teenagers and young adults, for whom the bedroom is, as Sian Lincoln (2005) writes, a domain ‘in which they are able to exert some control, be creative and make that space their own’ (p. -

Digital Humanities Pedagogy: Practices, Principles and Politics

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/161 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Digital Humanities Pedagogy: Practices, Principles and Politics Edited by Brett D. Hirsch http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2012 Brett D. Hirsch et al. (contributors retain copyright of their work). Some rights are reserved. The articles of this book are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported Licence. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Details of allowances and restrictions are available at: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ As with all Open Book Publishers titles, digital material and resources associated with this volume are available from our website at: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/161 ISBN Hardback: 978-1-909254-26-8 ISBN Paperback: 978-1-909254-25-1 ISBN Digital (pdf): 978-1-909254-27-5 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-909254-28-2 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 978-1-909254-29-9 Typesetting by www.bookgenie.in Cover image: © Daniel Rohr, ‘Brain and Microchip’, product designs first exhibited as prototypes in January 2009. Image used with kind permission of the designer. For more information about Daniel and his work, see http://www.danielrohr.com/ All paper used by Open Book Publishers is SFI (Sustainable Forestry Initiative), and PEFC (Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification Schemes) Certified. -

Illinois ... Football Guide

796.33263 lie LL991 f CENTRAL CIRCULATION '- BOOKSTACKS r '.- - »L:sL.^i;:f j:^:i:j r The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return to the library from which it was borrowed on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutllotlen, UNIVERSITY and undarllnlnfl of books are reasons OF for disciplinary action and may result In dismissal from ILUNOIS UBRARY the University. TO RENEW CAll TEUPHONE CENTEK, 333-8400 AT URBANA04AMPAIGN UNIVERSITY OF ILtlNOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN APPL LiFr: STU0i£3 JAN 1 9 \m^ , USRARy U. OF 1. URBANA-CHAMPAIGN CONTENTS 2 Division of Intercollegiate 85 University of Michigan Traditions Athletics Directory 86 Michigan State University 158 The Big Ten Conference 87 AU-Time Record vs. Opponents 159 The First Season The University of Illinois 88 Opponents Directory 160 Homecoming 4 The Uni\'ersity at a Glance 161 The Marching Illini 6 President and Chancellor 1990 in Reveiw 162 Chief llliniwek 7 Board of Trustees 90 1990 lUinois Stats 8 Academics 93 1990 Game-by-Game Starters Athletes Behind the Traditions 94 1990 Big Ten Stats 164 All-Time Letterwinners The Division of 97 1990 Season in Review 176 Retired Numbers intercollegiate Athletics 1 09 1 990 Football Award Winners 178 Illinois' All-Century Team 12 DIA History 1 80 College Football Hall of Fame 13 DIA Staff The Record Book 183 Illinois' Consensus All-Americans 18 Head Coach /Director of Athletics 112 Punt Return Records 184 All-Big Ten Players John Mackovic 112 Kickoff Return Records 186 The Silver Football Award 23 Assistant -

Hawks' Herald -- April 7, 2011 Roger Williams University

Roger Williams University DOCS@RWU Hawk's Herald Student Publications 4-7-2011 Hawks' Herald -- April 7, 2011 Roger Williams University Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/hawk_herald Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Roger Williams University, "Hawks' Herald -- April 7, 2011" (2011). Hawk's Herald. Paper 140. http://docs.rwu.edu/hawk_herald/140 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hawk's Herald by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. S' HERALD The student uewspaper of Roget WiLLidms University Vol. 20. Issue 16 www.hawbh.:rald.com :\pnl - . 2011 They're Sweetest thing watching Cake Off iced in charity, frosting you Cameras installed behind Willow, Cedar NICHOLLE BUCKLEY ICopy Editor New cameras have recently been installed behind Cedar I Iall and Willow Hall, and they have residents feeling uneasy rather than secure. John Blessing, Director of Public Safety, said that the cameras aren't a punishment or cause of worry; rather, they are merely an additional secu rity measure. Blessing says the cameras are part of a security initiative that the university be ~n undergoing a few years ago. 'We brought in a consultant company to review the cam pus, existing cameras, and blue lights, and determine what we'd need moving forward for secu rity," Blessing said. Blessing said that cameras can be found in the most public or "common" areas of the campus, such as entrances and exits, near residence halls, and rhe Com- . -

Sportsnews1961january Dece

" UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION AND ATHLETICS MINNEAPOLIS 14 i-~'HHHHHHHHHHHHH'~-lHHHHHHHHHHl* 1961 GOIF BROCHURE "The Gophers" The Schedule March 2(}.21 Rice at Houston, Texas April 26 Carleton Here May 6 Iowa, Wisconsin at Iowa City May 19-20 Conference Meet at Bloomington, Ind. June 19-24 NCAA Meet at Lafayette, Ind. 1960 Minnesota Golf Results Minn. Opp. 23t St. Thomas 3} 16~ Maca1ester l~ 17 Hamline 1 29 Iowa 25 15 Wisconsin 21 27 Wisconsin 201. 22 Northwestern 13 181 Iowa 171 20 Alumni 10 21 Minneapolis Golf Club 15 Placed Fourth in Conference Meet *****i'MHHHh\~<iHHHH.YHHP,******",HHHHHHHfo This brochure was prepared by the Sports Information Office, University of Minnesota. For further information contact Otis'J. Dypwick, Sports Information Director, Room 208 Cooke Hall, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis 14, Minnesota. - 2·- 1961 MINNESOTA GOLF PROSPECTS "Minnesota's golf outlook is the brightest in years.IV That optimistic statement is how veteran Gopher coach Les Bolstad views his team's prospects for the 1961 season. riAnything can happen in the Big 10, but we're aiming for as high as we can go,a Bolstad declares. Biggest factors in the rosy outlook, according to Bolstad, are experience and balance. The Gophers top four men, Gene Hansen, Capt. Carson Herron, Rolf Deming, and Jim Pfleider are extremely well matched, and Bolstad says he can't chose between them as to excellence. The other members of the squad's top six are Harry Newby and Les Peterson. Bolstad hopes his squad will continue the great improvement demonstrated last year when the Gophers catapulted from ninth to fourth place and almost finished second. -

Davince Tools Generated PDF File

alachi Puts' Finger On Old Gangland Crony WAS~I1~GTON . (,\P)_ ,Toseph i s!aYi,ngs arc still markccl ".lc·1 world death sentence. against I Valach! said . the l1:ish 'nob! Valu(!hi said the gang, bosse:! Valaclu put the fmger 011 an old 1 hve.' Thc slayers arc labeled i mcn who traccd thcu' ba~k· was "domg a little stIckup job I by S a I valor e Maranzano, gangland crony Tucsday as the "persons unknown." I ground to a small village in Ihere and there, hut it was wanted new faces so the riv;ll triggcr man in a scrics of mob \ Chairman John L. l\ICCICllanll Sicily. dangerous ... and they weren't mob of G ius e p p e Mass~ria war slayings 33 years ago. (Dem. Ark. of tIl c Scn· He said at one point that a making any money." wouldn't recognize\ its person· E The man, Valachi told invl!s, ate investigations subcommittee I ganglal1l1 lender had condemned Then came a 44·montb break, ne\. And he said the !\IaranzallO ligating senators in. a ramblin.~ II said Valachi's testimony ~hollld \ to death everyone who came while Valachi served a sentence group had only about 15 memo disjoin\ed llccount of the gang give police new leads in their from the Sicilian village called for a factory burglary. bers, and needed more. hattIe he calls "the Castella., efforts to catch the killers. i Castel del ;\Iar-and lhat '.vas When he got ollt, Valaehi said. That's where the chart came marese WaL'," was Girolamo I Secking vengeance againstllhe ancestral home of most cof 1he formed his own gang to pull: in. -

Brand Management Strategy for Korean Professional Football Teams

Brand Management Strategy for Korean Professional Football Teams : A Model for Understanding the Relationships between Team Brand Identity, Fans’ Identification with Football Teams, and Team Brand Loyalty A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ja Joon Koo School of Engineering and Design Brunel University March 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank many individuals without whom the completion of this dissertation would not have been possible. In particular, I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my supervisor Dr. Ray Holland who has supported my research with valuable advice and assistance. I also wish to extend express thankfulness for my college Gwang Jin Na. His valuable comments were much appreciated to conduct LISREL. In addition, my special thanks go to all respondents who completed my survey. Finally, but definitely not least, I would like to give my special appreciation to my family. To my parent, thank you for their endless love and support. I thank my brother, Ja Eun for his patience and encouragement throughout this process. Especially, my lovely wife, Mee Sun and son, Bon Ho born during my project have encouraged me to complete this dissertation not to give up. I am eternally grateful to all of you. i ABSTRACT This research recommends a new approach to brand strategy for Korean professional football teams, focusing on the relationships between team brand identity as the basic element of sports team branding, team brand loyalty as the most desirable goal, and identification between fans and teams as the mediator between identity and loyalty. Nowadays, professional football teams are no longer merely sporting organisations, but organisational brands with multi-million pound revenues. -

Governs the Making of Photocopies Or Other Reproductions of Copyrighted Materials

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. University of Nevada, Reno Fathom: A Collection of Short Stories A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS IN ENGLISH—WRITING AND THE HONORS PROGRAM by IRIS SALTUS Susan Palwick, Ph.D., Thesis Advisor May, 2013 UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA THE HONORS PROGRAM RENO We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by IRIS SALTUS entitled Fathom: A Collection of Short Stories be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS IN ENGLISH—WRITING AND THE HONORS PROGRAM ______________________________________________ Susan Palwick, Ph.D., Thesis Advisor ______________________________________________ Tamara Valentine, Ph.D., Director, Honors Program May, 2013 i ABSTRACT This collection of short stories explores four different psychological disorders: post-traumatic stress disorder, impulse control disorder, substance abuse disorder, and bipolar disorder. The goal of this exploration is to expose a narrative of each disorder. By going into the lives of the different characters portrayed in the short stories, an insight into these disorders is presented to the reader. -

2011 – Cincinnati, OH

Society for American Music Thirty-Seventh Annual Conference International Association for the Study of Popular Music, U.S. Branch Time Keeps On Slipping: Popular Music Histories Hosted by the College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza 9–13 March 2011 Cincinnati, Ohio Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind.