Civil Society, the State and Democracy in Zimbabwe, 1988 –

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Shoulders of Struggle, Memoirs of a Political Insider by Dr

On the Shoulders of Struggle: Memoirs of a Political Insider On the Shoulders of Struggle: Memoirs of a Political Insider Dr. Obert M. Mpofu Dip,BComm,MPS,PhD Contents Preface vi Foreword viii Commendations xii Abbreviations xiv Introduction: Obert Mpofu and Self-Writing in Zimbabwe xvii 1. The Mind and Pilgrimage of Struggle 1 2. Childhood and Initiation into Struggle 15 3. Involvement in the Armed Struggle 21 4. A Scholar Combatant 47 5. The Logic of Being ZANU PF 55 6. Professional Career, Business Empire and Marriage 71 7. Gukurahundi: 38 Years On 83 8. Gukurahundi and Selective Amnesia 97 9. The Genealogy of the Zimbabwean Crisis 109 10. The Land Question and the Struggle for Economic Liberation 123 11. The Post-Independence Democracy Enigma 141 12. Joshua Nkomo and the Liberation Footpath 161 13. Serving under Mugabe 177 14. Power Struggles and the Military in Zimbabwe 205 15. Operation Restore Legacy the Exit of Mugabe from Power 223 List of Appendices 249 Preface Ordinarily, people live to either make history or to immortalise it. Dr Obert Moses Mpofu has achieved both dimensions. With wanton disregard for the boundaries of a “single story”, Mpofu’s submission represents a construction of the struggle for Zimbabwe with the immediacy and novelty of a participant. Added to this, Dr Mpofu’s academic approach, and the Leaders for Africa Network Readers’ (LAN) interest, the synergy was inevitable. Mpofu’s contribution, which philosophically situates Zimbabwe’s contemporary politics and socio-economic landscape, embodies LAN Readers’ dedication to knowledge generation and, by extension, scientific growth. -

Domestic Resource Mobilisation and the Quest for Sustainable

Authored By Gorden Moyo Reviewed & Edited By John Maketo ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE INITIATIVE (EGI) REVIEWED & EDITED BY John Maketo (Programmes Manager) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ZIMCODD would like to acknowledge frantic efforts by the Executive Director, Janet Zhou, for providing leadership in this project, the lead researcher for this paper, Gorden Moyo, who worked tirelessly to put the pieces together for this publication. This publication was produced by the Zimbabwe Coalition on Debt and Development in collaboration with the Economic Governance Initiative Consortium in Zimbabwe comprised of the Transparency International Zimbabwe, Udugu Institute, Youth Empowerment and Transformation Trust (YETT) and the Vendors Initiative for Social and Economic Transformation (VISET) REVIEWED & EDITED BY John Maketo (Programmes Manager) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ZIMCODD would like to acknowledge frantic efforts by the Executive Director, Janet Zhou, for providing leadership in this project, the lead researcher for this paper, Gorden Moyo, who worked tirelessly to put the pieces together for this publication. This publication was produced by the Zimbabwe Coalition on Debt and Development in collaboration with the Economic Governance Initiative Consortium in Zimbabwe comprised of the Transparency International Zimbabwe, Udugu Institute, Youth Empowerment and Transformation Trust (YETT) and the Vendors Initiative for Social and Economic Transformation (VISET) TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS Table Of Contents i 4IR - Fourth Industrial Revolution Abbreviations and -

19 October 2009 Edition

19 October 2009 Edition 017 HARARE-Embattled‘I Deputy Agriculturewill Minister-Designate not quit’He was ordered to surrender his passport and title deeds of Roy Bennett has vowed not to give up politics despite his one of his properties and not to interfere with witnesses. continued ‘persecution and harassment.’ His trial was supposed to start last week on Tuesday at the Magistrate Court, only to be told on the day that the State was “I am here for as long as I can serve my country, my people applying to indict him to the High Court. The application was and my party to the best of my ability. Basically, I am here until granted the following day by Magistrate Lucy Mungwira and we achieve the aspirations of the people of Zimbabwe,” said he was committed to prison. Bennett in an interview on Saturday, quashing any likelihood that he would leave politics soon. On Friday, Justice Charles Hungwe reinstated his bail granted He added: “I have often thought of it (quitting) and it is an by the Supreme Court in March, resulting in his release. easiest thing to do, by the way. But if you have a constituency you have stood in front of and together you have suffered, “It is good to be out again, it is not a nice place (prison) to be. there is no easy walking away from that constituency. There are a lot of lice,” said Bennett. He said he had hoped So basically I am there until we return democracy and that with the transitional government in existence he would freedoms to Zimbabwe.” not continue to be ‘persecuted and harassed”. -

Get Statement

Debating Zimbabwe’s Land Reform IAN SCOONES This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivs 3.0 Unported License. Correct citation: Scoones, I. (2014). Debating Zimbabwe’s Land Reform. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies Photo credits: Photography is by B.Z. Mavedzenge. Front cover: Ruchanyu garden. Back cover: Rwafa maize crop ISBN: 978-1-4936-8062-7 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword vii About the author x Acronyms xi Section A: Agricultural and livestock production 1 1 Small farms, big farms 4 2 The golden leaf: boom time in Zimbabwe 9 3 The sweet smell of success: the revival of Zimbabwe’s 12 sugar industry 4 Farming under contract 17 5 Zimbabwe’s beef industry 21 6 Zimbabwe’s poultry industry: rapid recovery, but major 24 challenges 7 Mechanising Zimbabwean agriculture 27 8 Appropriate technologies? 30 Section B: The economy 33 9 Resource nationalism’: a risk to economic recovery? 36 10 Growth in jeopardy? Re!ections on Zimbabwe’s 2013 39 budget statement 11 An unbalanced economy 41 12 The new farm workers: Changing agrarian labour 44 dynamics 13 Transforming Zimbabwe’s agrarian economy 48 14 Credit and "nance 53 15 The whites who stayed in agriculture 55 iv Section C: Political dimensions 58 16 Robert Mugabe… what happened? 61 17 Missing politics? 65 18 Class and rural di#erentiation after land reform 71 19 Know your constituency: a challenge for all of 73 Zimbabwe’s political parties 20 Transforming the state: building security from below 77 21 Why nations fail: perspectives on Zimbabwe 81 -

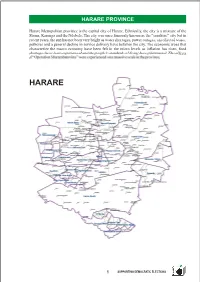

ZESN Book Final

HARARE PROVINCE The table also reveals that the number of voters per ward is higher in urban provinces than provinces that are largely rural. This is evidenced by the fact that the average number voters for Harare and Harare Metropolitan province is the capital city of Harare. Ethnically, the city is a mixture of the Bulawayo is 9826 and 10808 respectively. The average number of voters per ward for provinces that Shona, Karanga and the Ndebele. The city was once famously known as the “sunshine” city but in Constituency Profile are largely rural is less than 3000. For example, Mashonaland central has 285 wards and the average recent years, the sun has not been very bright as water shortages, power outages,HARARE uncollected PROVINCE waste, number of voters per ward is 1713. Masvingo has 242 wards and the average number of voters per potholes and a general decline in service delivery have befallen the city. The economic woes that ward is 2889. This has implications for the number of voters that will be able to cast their votes in the characterize the macro economy have been felt in the micro levels as inflation has risen, food March 29 harmonized elections. The electorate in Bulawayo and Harare provinces will experience shortages have been experienced and the people's standards of living have plummeted. The effects pressure during polls as a large number of voters have been crowded in a few wards. of “Operation Murambatsvina” were experienced on a massive scale in the province. In the 2002 presidential election, some urban voters who wished to cast their votes were not able to do as there were long queues and these discouraged voters from casting their votes. -

Towards a Framework for Resolving the Justice and Reconciliation Question in Zimbabwe

Towards a framework for resolving the justice and reconciliation question in Zimbabwe Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni and Everisto Benyera* Abstract Zimbabwe has never had meaningful and comprehensive programmes to provide justice in the many issues that cascade from conflict and violence in the nation. What has been done, amounts to armistices rather than transitional justice mechanisms. Consequently, Zimbabwe has not seriously dealt with the primary sources of conflict and violence that date back to colonial times. The rhetoric of unity premised on amnesia has been privileged over effective practical healing and reconciliation mechanisms that address the root causes of recurrent human rights violations. Indemnities, amnesties and presidential pardons have been used to protect perpetrators of conflict and violence. This article attempts to explore key issues and challenges around the healing and reconciliation question by exposing the contending perspectives and issues provoked by the adoption of the new constitution in Zimbabwe and the setting up of the National Peace and Reconciliation Commission (NPRC). Theoretically, the article posits that the very logic that informs the construction of ‘the political’ (as a domain of political values and incubator of political practices), which privileges notions of ‘the will to power’ and the ‘paradigm of war’, makes conflict and violence to be accepted as normal. Practically, the article advances ideas * Prof Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni is Head of the Archie Mafeje Research Institute (AMRI) at the University of South Africa (UNISA). Dr Everisto Benyera is a Lecturer in the Department of Political Sciences at the same university. 9 Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni and Everisto Benyera of ‘survivor’s justice’ as opposed to the traditional ‘criminal justice’ that fragments a society emerging from a catalogue of conflicts and violence into simplistic ‘perpetrator’ and ‘victim’ binaries. -

Editorial Archive July

Greek capitalism at a critical point Stamatis Karayannopoulos 2 October 2013 Greek capitalism continues to be the weak link of the Eurozone as it is still under the “intensive care” of the EU support mechanisms for the fourth consecutive year and is in recession for the sixth consecutive year. Overall GDP decline since the crisis began will reach 25% by the end of 2013 and unemployment will reach 30%. According to the Institute of Labour (INE) of the Greek General Greek General Confederation of Labour (GSEE) it will take at least 20 years to return to the pre-crisis levels! With growing rage, millions of workers, pensioners, small traders and young people who have been crushed by the austerity measures of the Memorandum are discovering what a big deception the so-called “rescue” of the country by the troika is. In reality it is a rescue of the speculators who hold the Greek debt and at the same time an attempt to avoid a domino effect of bankruptcies that could lead to the end of the Eurozone. In 2009 the Greek debt had reached 298.5 billion Euros and 128.9% of GDP. By the end of 2013, after three and a half years of such “rescue”, the debt will be 330 billion Euros and 178.5% of GDP. Up to June of this year, Greece had received 219 billion Euros from the Troika. Only 7.6 billion of this money went to towards alleviating the deficit, the rest was spent on recapitalising the banks and paying off part of the debt and the interest on the debt. -

Zimbabwe: Time for a New Approach

Zimbabwe: time for a new approach September 2011 Report of the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute (IBAHRI) Supported by the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (OSISA) This report has been compiled in accordance with the Lund – London Guidelines 2009 (www.factfindingguidelines.org) Material contained in this report may be freely quoted or reprinted, provided credit is given to the International Bar Association International Bar Association 4th Floor, 10 St Bride Street London EC4A 4AD, United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)20 7842 0090 Fax: +44 (0)20 7842 0091 Website: www.ibanet.org Contents Glossary of Acronyms 5 Executive Summary 7 Introduction 9 The mission 10 Section One: The Global Political Agreement 11 Historical background, context and results 11 Material contained in this report may be freely quoted or reprinted, provided credit is given to the International Bar Association Political participation and preparations for the next elections 15 The constitutional review process 19 Section Two: Rule Of Law 24 Independence and needs of the judiciary 24 The Attorney-General 27 Prosecutions for crimes committed in relation to the 2008 elections 29 Continuing selective application of the rule of law 30 National reconciliation 33 Zimbabwe Human Rights Commission 37 Section Three: The Extractive Industries 39 Human rights concerns 40 International Bar Association 4th Floor, 10 St Bride Street Relocation of local inhabitants from Marange to Arda Transau 41 London EC4A 4AD, United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)20 7842 0090 Fax: +44 -

Africa Report

PROJECT ON BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD AFRICA REPORT Second Quarterly Report on Africa April to June 2008 Volume: 1 Reports for the period April to May 2008 Principal Investigator: Prof. Dr. Ijaz Shafi Gilani Contributors Abbas S Lamptey Snr Research Associate Reports on Sub-Saharan AFrica Abdirisak Ismail Research Assistant Reports on East Africa INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD AFRICA REPORT Second Quarterly Report on Asia April to June 2008 Reports for the period April to May 2008 Volume: 1 Department of Politics and International Relations International Islamic University Islamabad 2 BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD AFRICA REPORT Second Quarterly Report on Africa 2008 Table of contents Reports for the month of April Week-1 April 01, 2008 05 Week-2 April 08, 2008 63 Week-3 April 15, 2008 120 Week-4 April 22, 2008 185 Week-5 April 29, 2008 247 Reports for the month of May Week-1 May 06, 2008 305 Week-2 May 12, 2008 374 Week-3 May 20, 2008 442 Country profiles Sources 3 4 BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD Weekly Presentation: April 1, 2008 Sub-Saharan Africa Abbas S Lamptey Period: From March 23 to March 29 2008 1. CHINA -AFRICA RELATIONS WEST AFRICA Sierra Leone: Chinese May Evade Govt Ban On Logging: Concord Times (Freetown):28 March 2008. Liberia: Chinese Women Donate U.S. $36,000 Materials: The NEWS (Monrovia):28 March 2008. Africa: China/Africa Trade May Hit $100bn in 2010:This Day (Lagos):28 March 2008. -

Situation Report C U R I T Y

Institute for Security Studies T E F O U R T I T S S E N I I D U S T E S Situation Report C U R I T Y Date Issued: 3 May 2004 Author: Chris Maroleng1 Distribution: General Contact: [email protected] Zimbabwe’s Movement for Democratic Change: Briefing notes Introduction Since attaining its independence from Britain in 1980, Zimbabwe has been ruled by one party, the Zimbabwe African National Union–Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF), led by the president, Robert Mugabe. Even though this country is considered a de jure democracy, credible opposition to ZANU-PF did not begin to emerge until the early 1990s, in a context of growing poverty and unemployment. The nationalist project represented by ZANU-PF in Zimbabwe has failed to provide the broad masses of its people with either human security or social peace. This deficiency is well treated by Patrick Bond and Masimba Manyanya in their most recent, comprehensive book, Zimbabwe’s plunge: Exhausted nationalism, neoliberalism, and the search for social justice, in which they observe that two decades after independence, fatigue associated with the ruling ZANU-PF’s misgovernment and economic mismanagement has clearly reached its nadir.2 The fact that Zimbabwe has reached a breaking point is also implied by Amanda Hammar and Brian Raftopoulos in their recent publication, Unfinished business: Rethinking land, state and citizenship in Zimbabwe. These authors note that the dramatic changes in Zimbabwe’s economic, political and social landscape since early 2000 have come to be known as the “Zimbabwe Crisis”.3 The steady decline in living standards throughout the 1990s is identified generally as one of the main reasons for the growing dissatisfaction with the government that in September 1999 galvanised civic groups and the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU) into forming a political party, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), currently led by Morgan Tsvangirai. -

Vol. 40, No. 4: Full Issue

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 40 Number 4 Fall 2012 Article 8 April 2020 Vol. 40, no. 4: Full Issue Denver Journal International Law & Policy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation 40 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Denver Sturm College of Law at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],dig- [email protected]. ' Denver Journal of International Law and Policy VOLUME 40 NUMBER 4 FALL-2012 TABLE OF CoNTENTs CASE NOTE ABDULLAHI v. PFIZER: SECOND CIRCUIT FINDS A NONCONSENSUAL MEDICAL EXPERIMENTATION CLAIM ACTIONABLE UNDER ALIEN TORT STATUTE ............... Anna Alman 533 ARTICLES TOWARDS A MORE REALISTIC VISION OF CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY THROUGH THE LENS OF THE LEX MERCATORIA...................... Jonathan Bellish 548 MICROFINANCE - Is THERE A SOLUTION? A SURVEY ON THE USE OF MFIS TO ALLEVIATE POVERTY IN INDIA ............. Jesse Fishman 588 SCIENCE FICTION No MORE: CYBER WARFARE AND THE UNITED STATES ................... CassandraM. Kirsch 620 A CONFLICT OF DIAMONDS: THE KIMBERLEY PROCESS AND ZIMBABWE'S MARANGE DIAMOND FIELDS ...... Julie Elizabeth Nichols 648 THE TROUBLE WITH WESTPHALIA IN SPACE: THE STATE-CENTRIC LIABILITY REGIME ..... Dan St. John 686 CASE NOTE ABDULLAHI V. PFIZER: SECOND CIRCUIT FINDS A NONCONSENSUAL MEDICAL EXPERIMENTATION CLAIM ACTIONABLE UNDER ALIEN TORT STATUTE Anna Alman* ABSTRACT United States courts struggle to determine what international human rights violations and against what violators could be raised under the Alien Tort Statute by non-U.S. -

Election Watch | Zimbabwe January 2012

Election Watch | Zimbabwe January 2012 MEASURING THE ZIMBABWEAN ELECTORAL ENVIRONMENT ACCORDING TO THE SADC GUIDELINES GOVERNING DEMOCRATIC ELECTIONS On the 17th of August 2004, the Southern African Development Commu- nity (SADC) leaders adopted the “SADC Principles and Guidelines Governing Democratic Elections.” As a member of SADC, Zimbabwe was a signatory to these benchmark principles, and therefore it is entirely fitting that Zimbabwe’s performance in relation to the future elections be measured against these principles and guidelines. The Electoral Institute for the Sustainability of Democracy in Africa presents a brief overview of Zimbabwe’s electoral system on their website. SADC principles for conducting democratic elections: Divergence/Obstructive Legislation Compliant 2.1.1 Full participa- • War veterans stormed the location at Vumba Mountains o Yes tion of citizens in where the Zimbabwe Constitution Select Committee S No the political process (COPAC) technical team has retreated for the drafting of the final document, demanding a halt in the constitu- tional drafting process • Citizenship of Zimbabwe Amendment Act, 2003 • Guardianship of Minors Act, 1961 • Broadcasting Services Act, 2001 www.idasa.org 2.1.2 Freedom of • Police defied a court order and disrupted an MDC-T rally o Yes association at Komayanga business centre in Nkayi, Matebeleland S No North • Public Order and Security Act, 2002, amended 2007 2.1.3 Political • A crackdown on Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai’s o Yes tolerance supporters has S No followed the bombing