Zimbabwe: Time for a New Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ZESN Book Final

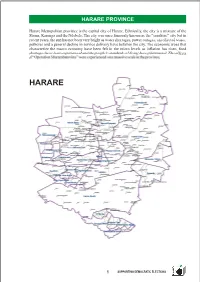

HARARE PROVINCE The table also reveals that the number of voters per ward is higher in urban provinces than provinces that are largely rural. This is evidenced by the fact that the average number voters for Harare and Harare Metropolitan province is the capital city of Harare. Ethnically, the city is a mixture of the Bulawayo is 9826 and 10808 respectively. The average number of voters per ward for provinces that Shona, Karanga and the Ndebele. The city was once famously known as the “sunshine” city but in Constituency Profile are largely rural is less than 3000. For example, Mashonaland central has 285 wards and the average recent years, the sun has not been very bright as water shortages, power outages,HARARE uncollected PROVINCE waste, number of voters per ward is 1713. Masvingo has 242 wards and the average number of voters per potholes and a general decline in service delivery have befallen the city. The economic woes that ward is 2889. This has implications for the number of voters that will be able to cast their votes in the characterize the macro economy have been felt in the micro levels as inflation has risen, food March 29 harmonized elections. The electorate in Bulawayo and Harare provinces will experience shortages have been experienced and the people's standards of living have plummeted. The effects pressure during polls as a large number of voters have been crowded in a few wards. of “Operation Murambatsvina” were experienced on a massive scale in the province. In the 2002 presidential election, some urban voters who wished to cast their votes were not able to do as there were long queues and these discouraged voters from casting their votes. -

"Our Hands Are Tied" Erosion of the Rule of Law in Zimbabwe – Nov

“Our Hands Are Tied” Erosion of the Rule of Law in Zimbabwe Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-404-4 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org November 2008 1-56432-404-4 “Our Hands Are Tied” Erosion of the Rule of Law in Zimbabwe I. Summary ............................................................................................................... 1 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................... 5 To the Future Government of Zimbabwe .............................................................. 5 To the Chief Justice ............................................................................................ 6 To the Office of the Attorney General .................................................................. 6 To the Commissioner General of the Zimbabwe Republic Police .......................... 6 To the Southern African Development Community and the African Union ........... -

Editorial Archive July

Greek capitalism at a critical point Stamatis Karayannopoulos 2 October 2013 Greek capitalism continues to be the weak link of the Eurozone as it is still under the “intensive care” of the EU support mechanisms for the fourth consecutive year and is in recession for the sixth consecutive year. Overall GDP decline since the crisis began will reach 25% by the end of 2013 and unemployment will reach 30%. According to the Institute of Labour (INE) of the Greek General Greek General Confederation of Labour (GSEE) it will take at least 20 years to return to the pre-crisis levels! With growing rage, millions of workers, pensioners, small traders and young people who have been crushed by the austerity measures of the Memorandum are discovering what a big deception the so-called “rescue” of the country by the troika is. In reality it is a rescue of the speculators who hold the Greek debt and at the same time an attempt to avoid a domino effect of bankruptcies that could lead to the end of the Eurozone. In 2009 the Greek debt had reached 298.5 billion Euros and 128.9% of GDP. By the end of 2013, after three and a half years of such “rescue”, the debt will be 330 billion Euros and 178.5% of GDP. Up to June of this year, Greece had received 219 billion Euros from the Troika. Only 7.6 billion of this money went to towards alleviating the deficit, the rest was spent on recapitalising the banks and paying off part of the debt and the interest on the debt. -

Land and Agrarian Reform in Former Settler Colonial Zimbabwe.Indd

3 A Decade of Zimbabwe’s Land Revolution: The Politics of the War Veteran Vanguard Zvakanyorwa Wilbert Sadomba Introduction The Zimbabwe state, governed since 1980 by a nationalist elite with origins in the liberation movement, has experienced complex dynamics and changes regarding class relations and power in a post-colonial settler economy. The state reached a climax of political polarisation during this last decade, from 2000 to 2010. In the first two decades of independence, the ruling nationalist class had enjoyed an alliance with settler capital forged during peace negotiations in 1979 at Lancaster House (see Horne 20011 and Selby 2006). The alliance antagonised and negated the aspirations of the liberation struggle expressed symbolically and concretely in terms of reversing a century old grievance over unequal colonial land ownership structures. War veterans were an ‘embodiment’ of this anti-colonial demand (Kriger 1995), although a scattered peasant movement had dominated land struggles until 1996 (see Moyo 2001). These war veterans, as a social category, were constituted by a movement of former military youth and so-called former refugees, whose nucleus were fighters of the Zimbabwe’s liberation war2. The conflict between the neocolonial state on the one hand and peasants and war veterans, on the other, intensified during the 1990s. The state had successfully managed to suppress the organisation of war veterans during the 1980s. However, in 1997, it conceded to provide for their welfare and financial demands and, LLandand aandnd AAgrariangrarian RReformeform iinn FFormerormer SSettlerettler CColonialolonial ZZimbabwe.inddimbabwe.indd 7799 228/03/20138/03/2013 112:40:392:40:39 80 Land and Agrarian Reform in Zimbabwe: Beyond White-Settler Capitalism as part of the conditions of a truce entered between war veterans and President Robert Mugabe, promised to redistribute land. -

Civil Society, the State and Democracy in Zimbabwe, 1988 –

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012) Title of the thesis or dissertation. PhD. (Chemistry)/ M.Sc. (Physics)/ M.A. (Philosophy)/M.Com. (Finance) etc. [Unpublished]: University of Johannesburg. Retrieved from: https://ujcontent.uj.ac.za/vital/access/manager/Index?site_name=Research%20Output (Accessed: Date). CIVIL SOCIETY, THE STATE AND DEMOCRACY IN ZIMBABWE, 1988 – 2014: HEGEMONIES, POLARITIES AND FRACTURES By ZENZO MOYO A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, University of Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Literature and Philosophy in Development Studies Supervisor: Professor David Moore August 2018 Declaration of originality I declare that Civil Society, the State and Democracy in Zimbabwe, 1988 – 2014: Hegemonies, Polarities and Fractures is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. Zenzo Moyo (Researcher) Signed: …… …… Date…23 July 2018…… ii ABSTRACT The post-independence ruling class in Zimbabwe carefully combined coercion and consent to assert its hegemony from the day it assumed state power. It implemented this through making use of both civil society and political society. -

JOURNAL of AFRICAN ELECTIONS Vol 4 No 2 Oct 2005 VOLUME 4 NO 2 1

JOURNAL OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS JOURNAL OF JOURNAL OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS Special Issue on Zimbabwe’s 2005 General Election Vol 4 No 2 Oct 2005 Vol Volume 4 Number 2 October 2005 VOLUME 4 NO 2 1 Journal of African Elections Special Issue on Zimbabwe’s 2005 General Election ARTICLES BY Peter Vale Norman Mlambo Sue Mbaya Lloyd M Sachikonye Choice Ndoro Bertha Chiroro Martin R Rupiya Sehlare Makgelaneng Volume 4 Number 2 October 2005 2 JOURNAL OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS Published by EISA 14 Park Rd, Richmond Johannesburg South Africa P O Box 740 Auckland Park 2006 South Africa Tel: +27(0)11 482 5495 Fax: +27(0)11 482 6163 e-mail: [email protected] © EISA 2005 ISSN: 1609-4700 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. Copy editor: Pat Tucker Printed by: Global Print, Johannesburg Cover photograph: Reproduced with the permission of the HAMILL GALLERY OF AFRICAN ART, BOSTON, MA, USA www.eisa.org.za VOLUME 4 NO 2 3 EDITORS Denis Kadima, EISA, Johannesburg Khabele Matlosa, EISA, Johannesburg EDITORIAL BOARD Tessy Bakary, Office of the Prime Minister, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire David Caroll, Democracy Program, The Carter Center, Atlanta Luis de Brito, EISA Country Office, Maputo Jørgen Elklit, Department of Political Science, University of Aarhus, Denmark Amanda Gouws, Department of Political Science, University of Stellenbosch Abdalla Hamdok, International -

Minister of Justice, Zimbabwe, Patrick Chinamasa Police Commissioner

University of Ballarat Branch ABN 38 579 396 344 March 1st 2011 For attention: Minister of Justice, Zimbabwe, Patrick Chinamasa Police Commissioner Augustine Chihuri Home Affairs (police) Minister Kembo Mohadi State Security (CIO) Minister Didymus Mutasa Wayne Bvudzijena (police spokesman) Zimbabwean officials (various, in Australia) To whom it may concern, My organisation, the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU), represents University staff in Australia. As President of the University of Ballarat Branch of the NTEU, I write in protest at the arrest, detention and torture of social justice activist and director of the Labor Law Centre at the University of Zimbabwe lecturer Munyaradzi Gwisai on February 19. My information is that Munyaradzi Gwisai and others have been charged with treason. Furthermore, a guilty verdict risks a sentence of death or life imprisonment. I understand that Munya, along with others detained with him, has been tortured during the process of interrogation. Confession under torture is an unacceptable breach of human and internationally recognised labor rights. Furthermore, it makes a mockery of the legal system in Zimbabwe and undermines fundamental rights to justice that all human beings should be entitled to. I understand that unions around the world and throughout Africa are moving to condemn recent actions taken with respect to Munyaradzi Gwisai and others arrested with him, including The Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), an organisation that I hold in great regard. I call on you to reply to organisations and individuals and explain the actions you are undertaking or plan to undertake to secure the release, without delay, of Munyaradzi Gwisai and the other 45 labor activists arrested on February 19. -

The Week's Top Stories

Defending free expression and the right to know The Media Monitoring Project Zimbabwe Monday June 7th - Sunday June 13th 2010 Weekly Media Review 2010-22 Contents 1. The week’s top stories 2. Distortion and censorship 3. The most popular voices THE WEEK’S TOP STORIES ALTHOUGH there was a significant increase in the media’s coverage of the constitutional reform programme compared to last week as the nation awaited the launch of the Constitutional Parliamentary Select Committee’s outreach exercise (by 58% in terms of the number of stories), the quality of the coverage still raised more questions than answers. Although COPAC inserted supplements in the Press identifying team members and venues for the consultation meetings in many of the country’s wards, there was no timetable for these meetings or any reassurances about the security of those making submissions. None of the media followed-up COPAC’s advertising initiative and few thought to pursue other issues of evident concern. In other stories, the Kimberley Process monitor Abbey Chikane’s alleged certification of Chiadzwa’s controversial diamonds sparked mixed reactions in the media and competed for attention alongside news of fresh tension in the coalition, ignited by blatant attempts to undermine the office of the Prime Minister by senior members of the ZANU PF arm of government. Fig 1: The most popular stories Media Inclusive Constitution Human Chiadzwa government reforms rights diamonds Public 14 14 7 10 Press ZBC 8 32 0 23 Private 22 8 13 12 papers Private 9 9 18 12 electronic media Total 53 63 38 57 Public media fail the nation IN THE week before the constitutional outreach consultation programme kicked off, there was still precious little effort by either the Constitutional Parliamentary Select Committee (COPAC) or the media to publicize essential issues about the exercise. -

Problems Mount on Copac's Outreach Programme

Defending free expression and your right to know The Media Monitoring Project Zimbabwe Monday August 30th – Sunday September 5th 2010 Weekly Media Review 2010-34 Contents 1. Top stories of the week 2. The media’s loudest voices 3. Human rights abuses Top stories of the week The visit by international music icons – US-based R&B singer Akon and his Jamaican Ragga counterpart, Sean Paul – as part of government efforts to rebrand the country’s battered image, hogged media limelight at the end of the week. But it was the crisis-ridden Constitutional Parliamentary Committee (Copac)’s consultation programme, bedevilled by funding and operational problems, which still received most publicity in both the government and private media during the week. Poor service delivery, especially by local government authorities and state-run companies, attracted significant media attention too. Fig. 1 illustrates this. Fig 1: Top stories in the media Media Akon/Sean Constitutional Poor service Labour Human Paul musical reforms delivery unrest rights show Public 22 30 26 7 2 Media Private 19 24 14 3 21 Media Total 41 54 40 10 23 Problems mount on Copac’s outreach programme News of the alleged reluctance by donors to fund the additional 25 days of the constitutional outreach programme marked the latest controversy to dog Zimbabwe’s constitution-making process in the week. But the media inadequately handled this development by largely failing to shine light on why the donors had rebuffed financing the extension of the exercise. Neither did they clear the confusion over the real reasons behind the extension given Copac’s controversial announcement in the week that it had allocated only two days for the outreach exercise in Harare and Bulawayo after initially giving the impression that the additional 25 days were mainly to accommodate the outreach programme in the two cities. -

…As EU Puts the Record Straight

For feedback email The New Age Voices on [email protected] Issue 14 14 - 27 Mar 2011 Youths, civil society scoffs at anti-sanctions propaganda YOUTH leaders, civil society and political peoples' struggle as they have stood at the activists in Zimbabwe have scoffed at the road to democracy in Zimbabwe. Zanu PF anti-sanctions crusade that is being propped has found a smokescreen to shield its crimes up by Zanu PF which climaxed with a committed against the people and justify its petition campaign launch and outreach that looting and plundering of national is chaired by Zanu PF second secretary, John resources. Nkomo. “Zanu PF has intensified its war against The New Age Voices visited several high the people and this has been guised as a “war density suburbs on the day of the launch and against sanctions”. It is young people who saw that shop owners and roadside traders have been causalities of Zanu PF's “war had been forced to close shop and attend the against sanctions”. It is therefore important launch. for both the local political leadership and Some residents who spoke to The New international community to make Age Voices said that many people in their meaningful steps aimed towards removal of areas failed to report for work while others sanctions. The restoration of human rights got into town late for fear of being hauled and dignity is definitely a pre requisite and into trucks and buses that were ferrying when such reforms begin the international people to the event. community should also make steps towards At the launch, Zanu PF leader President reengagement,” Chamunogwa said. -

ZIMBABWE COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

ZIMBABWE COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service 25 March 2011 ZIMBABWE 25 MARCH 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN ZIMBABWE FROM 22 FEBRUARY 2011 TO 24 MARCH 2011 Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON ZIMBABWE PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 22 FEBRUARY 2011 AND 24 MARCH 2011 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Public holidays ..................................................................................................... 1.06 Map ........................................................................................................................ 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 Remittances .......................................................................................................... 2.06 Sanctions .............................................................................................................. 2.08 3. HISTORY (19TH CENTURY TO 2008)............................................................................. 3.01 Matabeleland massacres 1983 - 87 ..................................................................... 3.03 Political events: late 1980s - 2007...................................................................... 3.06 Events in 2008 - 2010 ........................................................................................... 3.23 -

ZIMBABWE COUNTRY REPORT April 2004

ZIMBABWE COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 COUNTRY INFORMATION & POLICY UNIT IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Zimbabwe April 2004 CONTENTS 1 Scope of the Document 1.1 –1.7 2 Geography 2.1 – 2.3 3 Economy 3.1 4 History 4.1 – 4.193 Independence 1980 4.1 - 4.5 Matabeleland Insurgency 1983-87 4.6 - 4.9 Elections 1995 & 1996 4.10 - 4.11 Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) 4.12 - 4.13 Parliamentary Elections, June 2000 4.14 - 4.23 - Background 4.14 - 4.16 - Election Violence & Farm Occupations 4.17 - 4.18 - Election Results 4.19 - 4.23 - Post-election Violence 2000 4.24 - 4.26 - By election results in 2000 4.27 - 4.28 - Marondera West 4.27 - Bikita West 4.28 - Legal challenges to election results in 2000 4.29 Incidents in 2001 4.30 - 4.58 - Bulawayo local elections, September 2001 4.46 - 4.50 - By elections in 2001 4.51 - 4.55 - Bindura 4.51 - Makoni West 4.52 - Chikomba 4.53 - Legal Challenges to election results in 2001 4.54 - 4.56 Incidents in 2002 4.57 - 4.66 - Presidential Election, March 2002 4.67 - 4.79 - Rural elections September 2002 4.80 - 4.86 - By election results in 2002 4.87 - 4.91 Incidents in 2003 4.92 – 4.108 - Mass Action 18-19 March 2003 4.109 – 4.120 - ZCTU strike 23-25 April 4.121 – 4.125 - MDC Mass Action 2-6 June 4.126 – 4.157 - Mayoral and Urban Council elections 30-31 August 4.158 – 4.176 - By elections in 2003 4.177 - 4.183 Incidents in 2004 4.184 – 4.191 By elections in 2004 4.192 – 4.193 5 State Structures 5.1 – 5.98 The Constitution 5.1 - 5.5 Political System: 5.6 - 5.21 - ZANU-PF 5.7 -