Zimbabwe: Increased Securitisation of the State?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zimbabwe News, Vol. 26, No. 6

Zimbabwe News, Vol. 26, No. 6 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuzn199506 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Zimbabwe News, Vol. 26, No. 6 Alternative title Zimbabwe News Author/Creator Zimbabwe African National Union Publisher Zimbabwe African National Union (Harare, Zimbabwe) Date 1995-11-00? Resource type Magazines (Periodicals) Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Zimbabwe, South Africa, Southern Africa (region) Coverage (temporal) 1995 Source Northwestern University Libraries, L968.91005 Z711 v.26 Rights By kind permission of ZANU, the Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front. Description Editorial. Letters. National News: ZANU PF urged to draw up election guidelines. -

KEMBO MOHADI Versus the STANDARD and STANDARD PRESS (PVT) LTD and DAVISON MARUZIVA and EDDIE CROSS

1 HH 16-13 HC 5517/09 KEMBO MOHADI versus THE STANDARD and STANDARD PRESS (PVT) LTD and DAVISON MARUZIVA and EDDIE CROSS HIGH COURT OF ZIMBABWE ZHOU J HARARE, 13 September 2012 and 17 January 2013 E.W.W. Morris for the excipient R. Dembure for the respondent ZHOU J: This is an exception to the plaintiff’s claim for damages for defamation on the ground that the words complained of carry no reference to the plaintiff and that the declaration makes no proper allegations of facts which would enable the ordinary reader to identify the plaintiff as the person defamed. The background to the dispute between the parties is as follows: The plaintiff is a Cabinet Minister in the current Government of Zimbabwe. He is co- Minister of Home Affairs. The second defendant is a publisher of a newspaper known as The Standard. The third defendant is employed by the second defendant as editor. The first defendant is the name of a newspaper. In its issue of The Standard of October 11-17, 2009 the second defendant published a letter authoured by the fourth defendant under the title “Criminal vandalism”. The full text of the letter is as follows: “DRIVING to Harare last week I saw an astonishing sight just outside Gweru. From Gweru to Harare, a distance of more than 250 kilometres, the electrical system built after independence at a cost of over US$100 million dollars, has been stripped and lies derelict and destroyed. 2 HH 16-13 HC 5517/09 Tens of millions of dollars damage carried out on the side of the main road and in front of the entire country and its police force. -

Get Statement

Debating Zimbabwe’s Land Reform IAN SCOONES This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivs 3.0 Unported License. Correct citation: Scoones, I. (2014). Debating Zimbabwe’s Land Reform. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies Photo credits: Photography is by B.Z. Mavedzenge. Front cover: Ruchanyu garden. Back cover: Rwafa maize crop ISBN: 978-1-4936-8062-7 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword vii About the author x Acronyms xi Section A: Agricultural and livestock production 1 1 Small farms, big farms 4 2 The golden leaf: boom time in Zimbabwe 9 3 The sweet smell of success: the revival of Zimbabwe’s 12 sugar industry 4 Farming under contract 17 5 Zimbabwe’s beef industry 21 6 Zimbabwe’s poultry industry: rapid recovery, but major 24 challenges 7 Mechanising Zimbabwean agriculture 27 8 Appropriate technologies? 30 Section B: The economy 33 9 Resource nationalism’: a risk to economic recovery? 36 10 Growth in jeopardy? Re!ections on Zimbabwe’s 2013 39 budget statement 11 An unbalanced economy 41 12 The new farm workers: Changing agrarian labour 44 dynamics 13 Transforming Zimbabwe’s agrarian economy 48 14 Credit and "nance 53 15 The whites who stayed in agriculture 55 iv Section C: Political dimensions 58 16 Robert Mugabe… what happened? 61 17 Missing politics? 65 18 Class and rural di#erentiation after land reform 71 19 Know your constituency: a challenge for all of 73 Zimbabwe’s political parties 20 Transforming the state: building security from below 77 21 Why nations fail: perspectives on Zimbabwe 81 -

ZESN Book Final

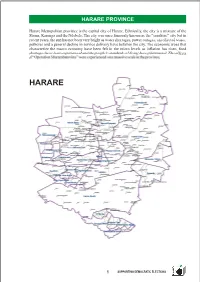

HARARE PROVINCE The table also reveals that the number of voters per ward is higher in urban provinces than provinces that are largely rural. This is evidenced by the fact that the average number voters for Harare and Harare Metropolitan province is the capital city of Harare. Ethnically, the city is a mixture of the Bulawayo is 9826 and 10808 respectively. The average number of voters per ward for provinces that Shona, Karanga and the Ndebele. The city was once famously known as the “sunshine” city but in Constituency Profile are largely rural is less than 3000. For example, Mashonaland central has 285 wards and the average recent years, the sun has not been very bright as water shortages, power outages,HARARE uncollected PROVINCE waste, number of voters per ward is 1713. Masvingo has 242 wards and the average number of voters per potholes and a general decline in service delivery have befallen the city. The economic woes that ward is 2889. This has implications for the number of voters that will be able to cast their votes in the characterize the macro economy have been felt in the micro levels as inflation has risen, food March 29 harmonized elections. The electorate in Bulawayo and Harare provinces will experience shortages have been experienced and the people's standards of living have plummeted. The effects pressure during polls as a large number of voters have been crowded in a few wards. of “Operation Murambatsvina” were experienced on a massive scale in the province. In the 2002 presidential election, some urban voters who wished to cast their votes were not able to do as there were long queues and these discouraged voters from casting their votes. -

Matebeleland South

HWANGE WEST Constituency Profile MATEBELELAND SOUTH Hwange West has been stripped of some areas scene, the area was flooded with tourists who Matebeleland South province is predominantly rural. The Ndebele, Venda and the Kalanga people that now constitute Hwange Central. Hwange contributed to national and individual revenue are found in this area. This province is one of the most under developed provinces in Zimbabwe. The West is comprised of Pandamatema, Matesti, generation. The income derived from tourists people feel they have been neglected by the government with regards to the provision of education Ndlovu, Bethesda and Kazungula. Hwange has not trickled down to improve the lives of and health as well as road infrastructure. Voting patterns in this province have been pro-opposition West is not suitable for human habitation due people in this constituency. People have and this can be possibly explained by the memories of Gukurahundi which may still be fresh in the to the wild life in the area. Hwange National devised ways to earn incomes through fishing minds of many. Game Park is found in this constituency. The and poaching. Tourist related trade such as place is arid, hot and crop farming is made making and selling crafts are some of the ways impossible by the presence of wild life that residents use to earn incomes. destroys crops. Recreational parks are situated in this constituency. Before Zimbabwe's REGISTERED VOTERS image was tarnished on the international 22965 Year Candidate Political Number Of Votes Party 2000 Jelous Sansole MDC 15132 Spiwe Mafuwa ZANU PF 2445 2005 Jelous Sansole MDC 10415 Spiwe Mafuwa ZANU PF 4899 SUPPORTING DEMOCRATIC ELECTIONS 218 219 SUPPORTING DEMOCRATIC ELECTIONS BULILIMA WEST Constituency Profile Constituency Profile BULILIMA EAST Bulilima West is made up of Dombodema, residents' incomes. -

The Mortal Remains: Succession and the Zanu Pf Body Politic

THE MORTAL REMAINS: SUCCESSION AND THE ZANU PF BODY POLITIC Report produced for the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum by the Research and Advocacy Unit [RAU] 14th July, 2014 1 CONTENTS Page No. Foreword 3 Succession and the Constitution 5 The New Constitution 5 The genealogy of the provisions 6 The presently effective law 7 Problems with the provisions 8 The ZANU PF Party Constitution 10 The Structure of ZANU PF 10 Elected Bodies 10 Administrative and Coordinating Bodies 13 Consultative For a 16 ZANU PF Succession Process in Practice 23 The Fault Lines 23 The Military Factor 24 Early Manoeuvring 25 The Tsholotsho Saga 26 The Dissolution of the DCCs 29 The Power of the Politburo 29 The Powers of the President 30 The Congress of 2009 32 The Provincial Executive Committee Elections of 2013 34 Conclusions 45 Annexures Annexure A: Provincial Co-ordinating Committee 47 Annexure B : History of the ZANU PF Presidium 51 2 Foreword* The somewhat provocative title of this report conceals an extremely serious issue with Zimbabwean politics. The theme of succession, both of the State Presidency and the leadership of ZANU PF, increasingly bedevils all matters relating to the political stability of Zimbabwe and any form of transition to democracy. The constitutional issues related to the death (or infirmity) of the President have been dealt with in several reports by the Research and Advocacy Unit (RAU). If ZANU PF is to select the nominee to replace Robert Mugabe, as the state constitution presently requires, several problems need to be considered. The ZANU PF nominee ought to be selected in terms of the ZANU PF constitution. -

Editorial Archive July

Greek capitalism at a critical point Stamatis Karayannopoulos 2 October 2013 Greek capitalism continues to be the weak link of the Eurozone as it is still under the “intensive care” of the EU support mechanisms for the fourth consecutive year and is in recession for the sixth consecutive year. Overall GDP decline since the crisis began will reach 25% by the end of 2013 and unemployment will reach 30%. According to the Institute of Labour (INE) of the Greek General Greek General Confederation of Labour (GSEE) it will take at least 20 years to return to the pre-crisis levels! With growing rage, millions of workers, pensioners, small traders and young people who have been crushed by the austerity measures of the Memorandum are discovering what a big deception the so-called “rescue” of the country by the troika is. In reality it is a rescue of the speculators who hold the Greek debt and at the same time an attempt to avoid a domino effect of bankruptcies that could lead to the end of the Eurozone. In 2009 the Greek debt had reached 298.5 billion Euros and 128.9% of GDP. By the end of 2013, after three and a half years of such “rescue”, the debt will be 330 billion Euros and 178.5% of GDP. Up to June of this year, Greece had received 219 billion Euros from the Troika. Only 7.6 billion of this money went to towards alleviating the deficit, the rest was spent on recapitalising the banks and paying off part of the debt and the interest on the debt. -

Zimbabwe-Lawyer Tortured-Open Letter-2003

INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION OF JURISTS Commission internationale de juristes - Comisión Internacional de Juristas " dedicated since 1952 to the primacy, coherence and implementation of international law and principles that advance human rights " 17 April 2003 Mr. Robert Mugabe President President JUSTICE ARTHUR CHASKALSON, South Africa Munhumutapa Building Harare - Zimbabwe Vice-Presidents LORD WILLIAM GOODHART, United Kingdom Mr. Patrick Chinamasa JUSTICE LENNART GROLL, Sweden Minister of Justice and Parliamentary Affairs Private Bag 7704 Executive Committee JUSTICE JOHN DOWD, Australia (Chairperson) Causeway - Zimbabwe PROF. JOCHEN A. FROWEIN, Germany ASMA JAHANGIR, Pakistan Fax: +263 4 772994 PROF. MAURICE KAMTO, Cameroon DR. HIPOLITO SOLARI YRIGOYEN, Argentina GLADYS VERONICA LI, Hong Kong Dear Sirs, PROF. YOZO YOKOTA, Japan The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) consists of jurists Other Commission Members who represent all the regions and legal systems in the world SOLOMY BALUNGI BOSSA, Uganda working to uphold the rule of law and the legal protection of ANTONIO CASSESE, Italy LORD COOKE, New Zealand human rights. The ICJ's Centre for the Independence of Judges MARIE JOSÉ CRESPIN, Senegal PARAM CUMARASWAMY, Malaysia and Lawyers (CIJL) is dedicated to promoting the independence DALMO DE ABREU DALLARI, Brazil of judges and lawyers throughout the world. RAJEEV DHAVAN, India VERA DUARTE, Cape-Verde DESMOND FERNANDO, Sri Lanka GUSTAVO GALLóN GIRALDO, Colombia We are writing to you to express our alarm at the violent RUTH GAVISON, Israel treatment of Mr Gabriel Shumba, a lawyer and member, until he ASMA KHADER, Jordan KOFI KUMADO, Ghana fled the country, of the Zimbabwean Human Rights NGO Forum. EWA LETOWSKA, Poland CLAIRE L'HEUREUX-DUBE, Canada FLORENCE N. -

Zimbabwe: Time for a New Approach

Zimbabwe: time for a new approach September 2011 Report of the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute (IBAHRI) Supported by the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (OSISA) This report has been compiled in accordance with the Lund – London Guidelines 2009 (www.factfindingguidelines.org) Material contained in this report may be freely quoted or reprinted, provided credit is given to the International Bar Association International Bar Association 4th Floor, 10 St Bride Street London EC4A 4AD, United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)20 7842 0090 Fax: +44 (0)20 7842 0091 Website: www.ibanet.org Contents Glossary of Acronyms 5 Executive Summary 7 Introduction 9 The mission 10 Section One: The Global Political Agreement 11 Historical background, context and results 11 Material contained in this report may be freely quoted or reprinted, provided credit is given to the International Bar Association Political participation and preparations for the next elections 15 The constitutional review process 19 Section Two: Rule Of Law 24 Independence and needs of the judiciary 24 The Attorney-General 27 Prosecutions for crimes committed in relation to the 2008 elections 29 Continuing selective application of the rule of law 30 National reconciliation 33 Zimbabwe Human Rights Commission 37 Section Three: The Extractive Industries 39 Human rights concerns 40 International Bar Association 4th Floor, 10 St Bride Street Relocation of local inhabitants from Marange to Arda Transau 41 London EC4A 4AD, United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)20 7842 0090 Fax: +44 -

Situation Report C U R I T Y

Institute for Security Studies T E F O U R T I T S S E N I I D U S T E S Situation Report C U R I T Y Date Issued: 3 May 2004 Author: Chris Maroleng1 Distribution: General Contact: [email protected] Zimbabwe’s Movement for Democratic Change: Briefing notes Introduction Since attaining its independence from Britain in 1980, Zimbabwe has been ruled by one party, the Zimbabwe African National Union–Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF), led by the president, Robert Mugabe. Even though this country is considered a de jure democracy, credible opposition to ZANU-PF did not begin to emerge until the early 1990s, in a context of growing poverty and unemployment. The nationalist project represented by ZANU-PF in Zimbabwe has failed to provide the broad masses of its people with either human security or social peace. This deficiency is well treated by Patrick Bond and Masimba Manyanya in their most recent, comprehensive book, Zimbabwe’s plunge: Exhausted nationalism, neoliberalism, and the search for social justice, in which they observe that two decades after independence, fatigue associated with the ruling ZANU-PF’s misgovernment and economic mismanagement has clearly reached its nadir.2 The fact that Zimbabwe has reached a breaking point is also implied by Amanda Hammar and Brian Raftopoulos in their recent publication, Unfinished business: Rethinking land, state and citizenship in Zimbabwe. These authors note that the dramatic changes in Zimbabwe’s economic, political and social landscape since early 2000 have come to be known as the “Zimbabwe Crisis”.3 The steady decline in living standards throughout the 1990s is identified generally as one of the main reasons for the growing dissatisfaction with the government that in September 1999 galvanised civic groups and the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU) into forming a political party, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), currently led by Morgan Tsvangirai. -

Vol. 40, No. 4: Full Issue

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 40 Number 4 Fall 2012 Article 8 April 2020 Vol. 40, no. 4: Full Issue Denver Journal International Law & Policy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation 40 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Denver Sturm College of Law at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],dig- [email protected]. ' Denver Journal of International Law and Policy VOLUME 40 NUMBER 4 FALL-2012 TABLE OF CoNTENTs CASE NOTE ABDULLAHI v. PFIZER: SECOND CIRCUIT FINDS A NONCONSENSUAL MEDICAL EXPERIMENTATION CLAIM ACTIONABLE UNDER ALIEN TORT STATUTE ............... Anna Alman 533 ARTICLES TOWARDS A MORE REALISTIC VISION OF CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY THROUGH THE LENS OF THE LEX MERCATORIA...................... Jonathan Bellish 548 MICROFINANCE - Is THERE A SOLUTION? A SURVEY ON THE USE OF MFIS TO ALLEVIATE POVERTY IN INDIA ............. Jesse Fishman 588 SCIENCE FICTION No MORE: CYBER WARFARE AND THE UNITED STATES ................... CassandraM. Kirsch 620 A CONFLICT OF DIAMONDS: THE KIMBERLEY PROCESS AND ZIMBABWE'S MARANGE DIAMOND FIELDS ...... Julie Elizabeth Nichols 648 THE TROUBLE WITH WESTPHALIA IN SPACE: THE STATE-CENTRIC LIABILITY REGIME ..... Dan St. John 686 CASE NOTE ABDULLAHI V. PFIZER: SECOND CIRCUIT FINDS A NONCONSENSUAL MEDICAL EXPERIMENTATION CLAIM ACTIONABLE UNDER ALIEN TORT STATUTE Anna Alman* ABSTRACT United States courts struggle to determine what international human rights violations and against what violators could be raised under the Alien Tort Statute by non-U.S. -

Land and Agrarian Reform in Former Settler Colonial Zimbabwe.Indd

3 A Decade of Zimbabwe’s Land Revolution: The Politics of the War Veteran Vanguard Zvakanyorwa Wilbert Sadomba Introduction The Zimbabwe state, governed since 1980 by a nationalist elite with origins in the liberation movement, has experienced complex dynamics and changes regarding class relations and power in a post-colonial settler economy. The state reached a climax of political polarisation during this last decade, from 2000 to 2010. In the first two decades of independence, the ruling nationalist class had enjoyed an alliance with settler capital forged during peace negotiations in 1979 at Lancaster House (see Horne 20011 and Selby 2006). The alliance antagonised and negated the aspirations of the liberation struggle expressed symbolically and concretely in terms of reversing a century old grievance over unequal colonial land ownership structures. War veterans were an ‘embodiment’ of this anti-colonial demand (Kriger 1995), although a scattered peasant movement had dominated land struggles until 1996 (see Moyo 2001). These war veterans, as a social category, were constituted by a movement of former military youth and so-called former refugees, whose nucleus were fighters of the Zimbabwe’s liberation war2. The conflict between the neocolonial state on the one hand and peasants and war veterans, on the other, intensified during the 1990s. The state had successfully managed to suppress the organisation of war veterans during the 1980s. However, in 1997, it conceded to provide for their welfare and financial demands and, LLandand aandnd AAgrariangrarian RReformeform iinn FFormerormer SSettlerettler CColonialolonial ZZimbabwe.inddimbabwe.indd 7799 228/03/20138/03/2013 112:40:392:40:39 80 Land and Agrarian Reform in Zimbabwe: Beyond White-Settler Capitalism as part of the conditions of a truce entered between war veterans and President Robert Mugabe, promised to redistribute land.