Assessing the Value of Community-Generated Historic Environment Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Time Team to Archaeology for All

From Time Team to Archaeology for All Dr Carenza Lewis University of Cambridge www.access.arch.cam.ac.uk www.access.arch.cam.ac.uk www.access.arch.cam.ac.uk Enhancing educational, economic and social well-being through active participation in archaeology. Higher Education Field Academy) Aim – To help widen participation in higher education through participation in archaeological excavation • Find out more about university • Contribute to university research • Develop confidence and deploy skills for life, learning and employment The first HEFA - Terrington 2005 “I really enjoyed it. The best bit was not knowing what we would find’ (NP) “It was hard work but I had a great time” (MS). “The kids were really enthusiastic, talking about it all the way home, asking questions…. It helps that they’re doing it themselves, not just watching” (SC) “All the students loved their experiences and are still talking about it! It was judged much ‘cooler’ than going to Alton Towers!” (EO). Coxwold Castleton Wiveton Binham Terrington St Hindringham Clement Gaywood Peakirk Acle Wisbech St Ufford Mary Castor Thorney Carleton Rode Sawtry Ramsey Isleham Garboldisham Chediston Houghton Willingham Cottenham Rampton Hessett Walberswick Riseley Swaffham Coddenham Girton Bulbeck Warnborough Great Long Sharnbrook Shelford Stapleford Bramford Shefford Melford Ashwell 2005 Pirton 2006 Manuden Thorrington Little Hallingbury 2007 West Mersea Mill Green 2008 Amwell 2009 Writtle 2010 N Daws Heath 2011 2012 0 miles 50 2013 2014 HEFA weather! WRI/13 HEFA teams, HEFA spirit -

R I N G L E M E R E 2 0

KE N TA RC H A E O LO G I C A LS O C I E T Y newnewIssue number 57ss ll ee tt tt ee Summerrr 2003 RI N G L E M E R E2 0 0 3 Inside 2-3 n March 2003 archaeolo- served to trap evidence of earli- Faversham Museum gists returned to Ringle- er activity below and it can & Time Team mere, near Sandwich, to now be seen that a major late Library Notes continue excavations at Neolithic settlement had exist- 4-5 the site where the spec- ed on the site of the barrow tacular early Bronze Age around 700-1000 years earlier. Lectures, Courses, gold cup was discovered The inhabitants of this settle- Conferences & Events in November 2001. This year’s ment used highly decorated 6-7 programme was again possible Grooved ware pottery and the Bayford Castle through the generosity of the assemblage of such pottery Anglo-Saxon & landowners, the Smith broth- from Ringlemere is now by far Medieval Conference ers of Ringlemere Farm. The the largest from Kent and one fig 1 8-9 work was funded by substan- of the largest from anywhere Notice Board tial grants from the KAS, the in south-east England. 10-11 BBC and the British Museum. Whether this coincidence of ‘Ideas & Ideals’ Progress of the excavation was location is purely fortuitous filmed throughout by a profes- remains to be considered in Baptists, sional team from the BBC (fig. the light of further excavation Independents & 1) and this should be screened, but some sort of link presently Separation from the as part of the new ‘Hidden seems possible. -

Time Team Guide to the Archaeological Sites of Britain & Ireland

TIME TEAM GUIDE TO THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES OF BRITAIN & IRELAND FREE DOWNLOAD Tim Taylor | 320 pages | 01 May 2011 | Transworld Publishers Ltd | 9781905026029 | English | London, United Kingdom Time Team Guide to the Archaeological Sites of Britain Ireland Tim Taylor. A really informative book for someone interested in archaeology and the early history of Great Britain. To ensure we are able to help you as best we can, please include your reference number:. BBC News. Name required. The disputed changes included hiring anthropologist Mary-Ann Ochota as a co-presenter, dispensing with other archaeologists and what he thought were plans to "cut down the informative stuff about the archaeology". Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Nik rated it it was amazing Jan 03, I agree to the Terms and Conditions. Time Team has had many companion shows during its run, including Time Team ExtraHistory Hunters — and Time Team Digs — whilst several spin-off books have been published. You are commenting using your Facebook account. It involved about a thousand members of the public in excavating test pits each one metre square by fifty centimetres deep. Share this: Twitter Facebook. Trivia About Time Team Guide t Time Team official website. Community Reviews. Matthew Rae rated it really liked it Oct 31, Middlethought rated it it was amazing Aug 05, To find out more, including how to control cookies, see here: Cookie Policy. In some cases the programme makers have followed the process of discovery at a large commercial or research excavation by another body, such as that to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the ending of the First World War at the Vampire dugout in Belgium. -

Updatedgwsrmap2018.Pdf

Gloucestershire Warwickshire Steam Railway BROADWAY Cheltenham Race Course - Winchcombe - Toddington - Broadway Childswickham Broadway The line between Broadway in the north and Cheltenham łViews over the fertile Vale of Evesham CHELTENHAM RACE GOTHERINGTON GREET WINCHCOMBE TODDINGTON BROADWAY Race Course in the south is Snowshill COURSE STATION STATION TUNNEL STATION STATION STATION over 14 miles long. There Buckland are stunning views of the Manor (NT) HAYLES ABBEY Cotswolds to the south and HALT east and the Malvern Hills Laverton 200 L to the west. 200 805 L 150 200 200 264 200 It passes through a 693 yard 264 L tunnel at Greet and over a L L 264 150 150 L 15 arch viaduct at Stanway. 260 440 200 200 Stanton L Stanway Viaduct Toddington Manor 15 arches, 42 feet above 3.5 miles 3.5 miles 1.5 miles 1 mile 4.75 miles Owned by the artist Damien Hirst the valley floor Shenbarrow Gradient Profile. Gradient: 1 in No. shown. L = Level Hill Toddington Stanway House and Fountain River Isbourne The tallest gravity fountain in the world. N Said to be one of only two rivers in England New Town Stanway ł which flow due north from their source Views of Bredon TODDINGTON HT Oxenton and Dumbleton Hills Greet Tunnel Hill 693 yards, second longest Didbrook P tunnel on a British heritage railway Dixton Hill Hailes Abbey English Heritage/NT Gotherington Gretton Greet Prescott Hill Speed hill climb motor HAYLES ABBEY HALT sport and home of the s GOTHERINGTON Bugatti Owners’ Club d Views to Tewkesbury Abbey WINCHCOMBE ł l (12th century) and the Salters ancient riverside town. -

The Old Mill, the Cross Childswickham, Broadway

The Old Mill, The Cross Childswickham, Broadway, Worcestershire Archaeological Evaluation for Mr M. Machnicki CA Project: CR0197 CA Report: CR0197_1 WSM71980 October 2019 The Old Mill, The Cross Childswickham, Broadway Worcestershire Archaeological Evaluation CA Project: CR0197 CA Report: CR0197_1 Document Control Grid Revision Date Author Checked by Status Reasons for Approved revision by A 23 October Alison Laurent Internal Clifford 2019 Roberts Coleman review Bateman B 25 October Alison Laurent External To address Clifford 2019 Roberts Coleman review comments from Bateman Aidan Smyth This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. © Cotswold Archaeology © Cotswold Archaeology The Old Mill, The Cross, Childswickham, Broadway, Worcestershire: Archaeological Evaluation CONTENTS SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 2 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 3 2. ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND ................................................................ 3 3. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................... 4 4. METHODOLOGY .............................................................................................. -

North Cotswolds Village News

North Cotswold Villages Childswickham, Murcot, Aston Somerville Broadway and Leedons Parks, Willersey, Hinton, Bretforton 16,924 hits on the internet in the first half of 2017 Village News July 2017 And don’t forget STOP PRESS http://www.village-news.org.uk FUTURE DATES FOR YOUR DIARY • Sunday 2nd July Outdoor Shakespeare at the Fleece Inn • Sat. 22nd, Sun. 23rd and Sun. 30th July André Rieu in Regal Cinema • Tuesday 25th July Beauty and the Beast at Broadway Cinema Club, Lifford Hall • Saturday, 26th August Childswickham Summer Fete • Friday, 15th Sept. Elvis is appearing at the Inn and Brasserie http://www.village-news.org.uk Send emails to [email protected] Visit the Childswickham web site http://www.childswickham.org.uk Next issue September 2017 Deadline August 10th Village News July/August 2017 Childswickham Church St Mary the Virgin Sunday Services at 10.30am Communion 2nd, 4th, and 5th Sundays Mission, Praise and Prayer 1st and 3rd Canon John Thompstone 01386 852930 Joan Barnet (Church Warden) 01386 858309 Carol Strotten (Church Warden) 01386 852312 Sunday services continue each week at 10.30am. We are always very pleased to welcome visitors and newcomers and believe our Ploughman’s Lunch welcome is second to none! th Wednesday, 26 July Sunday, 11th June Trinity Sunday Childswickham Hall 12.00 for 12.30pm From the Registers:- £8.00 Two courses inc cordial Baptism Florence Jennifer Louise Cumberland Bring your own wine & glass Interment of Ashes Edward Charles Amey In aid of flower fund and Ann K Tredwell Tickets -

Childswickham BROADWAY • WORCESTERSHIRE • WR12 7HR NEW HOMES, MURCOT ROAD Childswickham BROADWAY • WORCESTERSHIRE WR12 7HR

Childswickham BROADWAY • WORCESTERSHIRE • WR12 7HR NEW HOMES, MURCOT ROAD Childswickham BROADWAY • WORCESTERSHIRE WR12 7HR One of three newly built family homes set in an attractive rural location with uninterrupted views to the front and rear Reception Hall • Drawing Room • Kitchen/Breakfast Room Utility Room • Downstairs WC • Master Bedroom with en-suite bathroom • Bedroom 2 with en suite • Bedroom 3 • Bedroom 4 Family Bathroom • Garage • Driveway • Garden Total Internal Floor Area 220sqm (2368sqft) Broadway 2 miles • M5 (J9) 11 miles • Evesham 5.2 miles (trains to London Paddington from 1 hour 41 minutes) • Winchcombe 9 miles • Cheltenham 15.5 miles • Stratford upon Avon 15.8 miles • Worcester 19.1 miles • Birmingham International Airport 34 miles • Central London 93 miles (Distances and times are approximate) These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. Situation • Kitchen / breakfast room with double doors leading out to the rear patio and garden Childswickham is a quietly situated village approximately 1 and ½ miles from Broadway and has a public house with • Fully fitted kitchen with natural stone flooring and a range of a restaurant and a church which serves the local community. painted and oak finish units with granite work surfaces and the following appliances:- Broadway village - often referred to as the “Jewel of the Cotswolds” - lies beneath Fish Hill on the western Cotswold • Integrated Neff fridge and freezer, Neff induction hob and escarpment and comprises a collection of period and extractor fan over, Neff slide and hide oven, Neff combination contemporary houses, with day to day shopping facilities oven/microwave and integrated Neff dishwasher including a library, health centre, bank, chemist, Budgens • Drawing Room with polished oak flooring, natural bath stone supermarket and a butcher. -

Tall Buildings URBAN DESIGN GROUP URBAN

Summer 2016 Urban Design Group Journal 13UR 9 BAN ISSN 1750 712X DESIGN TALL BUILDINGS URBAN DESIGN GROUP URBAN DESIGN GROUP NewsUDG NEWS more than this, with people being seen col- Nottingham and Bristol respectively. VIEW FROM THE lectively because of their ‘social values and Noha Nasser and the awards panel CHAIR responsibilities’. As urban designers we are for• continuing to grow the Urban Design members of a community. We share similar Awards. values and take on the duty of improving the Ben van Bruggen and Amanda Reynolds quality of life for people who live and work for• their ongoing stewardship of the Recog- in cities, towns and villages. nised Practitioner scheme. This is the last View from the Chair that I will I would like to use this last article to Barry Sellers for providing oral evidence write for Urban Design and it gives me an thank people within the Urban Design Group on• the Urban Design Group's behalf at the opportunity to reflect on the last two years community for continuing to strive to raise House of Lords' Built Environment Select of my tenure. The time has flown by! the standards in urban design practice. Lack Committee. At last March’s National Urban Design of space precludes me from mentioning The various regional conveners of events, Awards I pondered with Graham Smith, a everyone but the list includes the following particularly• Paul Reynolds and Philip Cave former lecturer at Oxford Brookes Universi- members of the community: in London; Peter Frankum in Southampton; ty, the use of the word ‘community’ for new Robert Huxford and Kathleen Lucey for Mark Foster and Hannah Harkis in Manches- developments. -

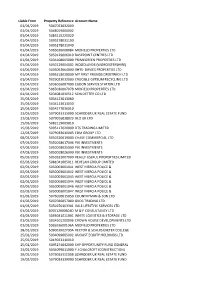

Liable from Property Reference Account Name 01/04/2019

Liable From Property Reference Account Name 01/04/2019 5047023032000 01/04/2019 5048019000002 01/04/2019 5083115220020 01/04/2019 5095278031100 01/04/2019 5095278031040 01/04/2019 50650360080B4 MIDFIELD PROPERTIES LTD 01/04/2019 5050129006010 BASEPOINT CENTRES LTD 01/04/2019 5034108005000 PRIMEGREEN PROPERTIES LTD 01/04/2019 5050129004002 WOODLANDS (WORCESTERSHIRE) 01/04/2019 5034052064000 RHYS- DAVIES PROPERTIES LTD 01/04/2019 5095218028030 MY FIRST FRIENDS DROITWICH LTD 01/04/2019 5029023032000 CRUCIBLE GYPSUM RECYCLING LTD 01/04/2019 5036016087000 EGDON SERVICE STATION LTD 01/04/2019 506503600707B MIDFIELD PROPERTIES LTD 01/04/2019 5034081030512 SCHLOETTER CO LTD 25/03/2019 5034123013060 25/03/2019 5034123013050 25/03/2019 5054177036010 23/03/2019 5079033315000 SCHRODER UK REAL ESTATE FUND 22/03/2019 5079016038023 ALO UK LTD 15/03/2019 5082119009010 15/03/2019 5095117020000 DTS TRADING LIMITED 12/03/2019 5079033010003 EDM GROUP LTD 08/03/2019 5050320019000 CHASE COMMERCIAL LTD 07/03/2019 5050018017006 PJK INVESTMENTS 07/03/2019 5050018025000 PJK INVESTMENTS 07/03/2019 5050018026000 PJK INVESTMENTS 05/03/2019 5050322007000 REALLY USEFUL PROPERTIES LIMITED 02/03/2019 5081041005011 REVELAN GROUP LIMITED 02/03/2019 5050003001041 WEST MERCIA POLICE & 02/03/2019 5050003001042 WEST MERCIA POLICE & 02/03/2019 5050003001043 WEST MERCIA POLICE & 02/03/2019 5050003001044 WEST MERCIA POLICE & 02/03/2019 5050003001046 WEST MERCIA POLICE & 02/03/2019 5050003001047 WEST MERCIA POLICE & 01/03/2019 5076010015050 COUNTRYMAN & SON LTD 01/03/2019 5037036057080 -

STOP PRESS This Is Intended to Highlight Events, with Some That Have Missed the Deadline for Hard Copy and Some Kept for Reference

Worcestershire Villages Childswickham, Murcot, Aston Somerville Broadway and Leedons Park, Willersey, Hinton on the Green, and Bretforton Over 20,000 hits on the internet in 2019 STOP PRESS This is intended to highlight events, with some that have missed the deadline for hard copy and some kept for reference. St Mary’s, Childswickham Notice Board Childswickham Parish Council update Childswickham Village Hall Activity Times and Contacts Wychavon Dog Control Orders The W I Going Going Gone at the Auctions Feel free to send me anything you need circulating [email protected] St Mary’s Church Noticeboard Carol Strotten, Churchwarden 01386 852312 Ralph Deakin, Churchwarden 01286 854605 Bell ringers: Tower Captain, Graham Lee 01386 858422 Families and children are always very welcome at St Mary's, do come along and join us. We would love to hear your suggestions of how we can best serve you all in the village. We now have a new hearing loop system installed so you can hear us at the back! The EZRA group meet on Saturday mornings between 8.30 and 9.30 to pray for the needs of our village community. Come and leave as time allows. Thank you to all who have supported us in 2019 and enabled the church to stay open and keep regular weekly services running. We look forward to working in close partnership with the ’Friends of St Mary’s’ during 2019. Come and join us as we share together in worship and fellowship. The Friends of St Mary's Church, Childswickham For over 850 years, the Church has played a pivotal part in village life and is a valued and much loved part of the village community. -

February 2016 and Don’T Forget STOP PRESS All the More Reason for Getting on Line

Worcestershire Villages Circulation to Childswickham, Murcot, Aston Somerville Broadway and Leedens Park, Willersey, Hinton, Bretforton 16400 hits on the internet! In 2015 V illage News- February 2016 And don’t forget STOP PRESS all the more reason for getting on line http://www.village-news.org.uk 13th 14th Valentines weekend at Childwickham Inn Bell ringers Needed see within Carpet Bowling continues at Childswickham Hall March April Gloucestershire Warwickshire Railway has a full menu Come and relive the 1940’s . Facebook links Childswickham Village or Worcestershire Hinton on the Green Appreciation Society Willersey Cotswolds Willersey a village not a town. Hinton on the Green Appreciation Society NOTA BENE Next issue articles please by Feb 10th for March edition Feb is a day longer but still a short month. Easter follows soon! http://www.village-news.org.uk This magazine was printed by Bear Print &Media Ltd Tel No. 01386 852522 07775 726543 See what they can do for you Send emails to [email protected] Visit the Childswickham web site http://www.childswickham.org.uk Next issue March 2016 Deadline Feb 10th Village News February 2016 Childswickham Church There is a church service every Sunday at St. Mary’s, Childswickham at 10.30am and you are welcome there, whatever your denomination or if you have never been to church before. 1st Sun Morning Worship 2nd Sun Holy Communion 3rd Sun Service with guest speaker, 4th Sun Holy Communion 5th Sun Morning Worship Sunday Jan 31st Bishop of Tewkesbury Feb 14th Rev Robert Pestell Chaplain from Cheltenham hospice Feb 28th Rev P Phillips. -

Pdf Childswickham

Childswickham Conservation Area Appraisal July 2005 CHILDSWICKHAM Conservation Area boundary Reproduced from the Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office (c) Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Wychavon District Council. Licence No. 100024324. Not to Scale Designated November 1969 First revision 12th July 2005 CONTENTS WHAT IS THIS STATEMENT FOR? ............................................................... 2 CHILDSWICKHAM CONSERVATION AREA ................................................. 3 ITS SPECIAL ARCHITECTURAL & HISTORIC INTEREST .......................... 3 LANDSCAPE SETTING .................................................................................. 3 HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT ...................................................................... 3 • Archaeology ..................................................................................................................... 3 • Origins and Development ................................................................................................. 4 CHARACTER AND APPEARANCE .............................................................. 8 DETAILED ASSESSMENT ........................................................................... 12 • Layout ............................................................................................................................ 12 • Architecture ...................................................................................................................