Gyrfalcon Diet: Spatial and Temporal Variation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gyrfalcon Falco Rusticolus

Gyrfalcon Falco rusticolus Rob Florkiewicz surveys, this area was included. Eight eyries are known from this Characteristics and Range The northern-dwelling Gyrfalcon is part of the province; however, while up to 7 of these eyries have the largest falcon in the world. It breeds mostly along the Arctic been deemed occupied in a single year, no more than 3 have been coasts of North America, Europe and Asia (Booms et al. 2008). productive at the same time. Based on these data and other Over its range, its colour varies from white through silver-grey to sightings, the British Columbia Wildlife Branch estimates the almost black; silver-grey is the most common morph in British breeding population in the province to be fewer than 20 pairs Columbia. It nests on cliff ledges at sites that are often used for (Chutter 2008). decades and where considerable amounts of guano can accumulate. Ptarmigan provide the Gyrfalcon's main prey in In British Columbia, the Gyrfalcon nests on cliff ledges on British Columbia and productivity appears dependent on mountains in alpine areas, usually adjacent to rivers or lakes. ptarmigan numbers. Large size and hunting prowess make the Occasionally, it nests on cliffs of river banks and in abandoned Gyrfalcon a popular bird with falconers, who breed and train Golden Eagle nests. them to hunt waterfowl and other game birds. Conservation and Recommendations Whilst the Gyrfalcon is Distribution, Abundance, and Habitat Most Gyrfalcons breed designated as Not at Risk nationally by COSEWIC, it is Blue-listed along the Arctic coast; however, a few breed in the northwest in British Columbia due to its small known breeding population portion of the Northern Boreal Mountains Ecoprovince of British (British Columbia Ministry of Environment 2014). -

Natural History of the Gyrfalcon in the Central Canadian Arctic K.G

ARCTIC VOL. 41, NO. 1 (MARCH 1988) P. 31-38 Natural History of the Gyrfalcon in the Central Canadian Arctic K.G. POOLE' and R.G. BROMLEY2 (Received 24 March 1987; accepted in revised form 24 September 1987) ABSTRACT. A population of breeding gyrfalcons was studied from 1982to 1986 on 2000a km2 area in thecentral Arctic of the NorthwestTerritories. Each year 14-18 territories were occupied. The meanintemest distance was 10.6 km, giving oneof the highest recorded densitiesfor the species. There was a tendency for regularity in spacing of territories. Most (85%) nests were in abandoned stick nests of common ravens or golden eagles. Rough-legged hawk nests were not used by gyrfalcons, despite numerous available.date Mean of initiation of laying was 8 May. Meansize of clutch was 3.80 and of brood was 2.53, and mean productivity was 1SO fledged young. A reduction of 48% from estimated numberof eggs laid to number of fledglings was determined. Reproductive success declined with increased severity of spring weather, notablydays increased and amount of precipitation. Key words: gyrfalcon (Falco rusticolus),natural history, reproductive ecology, central Arctic RÉSUMÉ. Qtre 1982 et 1986, on a étudié une populationde gerfauts en reproduction dans une zone de 2000 km2dans la région centrale arctiquedes Territoires du Nord-Ouest. Quatorze des 18 aires étaient occupées chaque année. La distance entremoyenne les nids étaitde 10,6km, soit la plus grande densité relevée pour cetteespèce. Les aires avaient tendanceB être espacéesrégulitrement. La plupart des nids(85 p. cent) étaient situésdans des nids de brindilles occupés précédemment pardes corbeaux communsou des aigles dorés. -

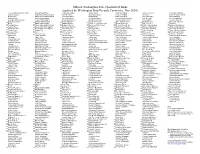

WBRC Review List 2020

Official Washington State Checklist of Birds (updated by Washington Bird Records Committee, Nov 2020) __Fulvous Whistling-Duck (1905) __White-throated Swift __Long-tailed Jaeger __Nazca Booby __Tropical Kingbird __Dusky Thrush (s) __Tricolored Blackbird __Emperor Goose __Ruby-throated Hummingbird __Common Murre __Blue-footed Booby __Western Kingbird __Redwing __Brown-headed Cowbird __Snow Goose __Black-chinned Hummingbird __Thick-billed Murre __Brown Booby __Eastern Kingbird __American Robin __Rusty Blackbird __Ross’s Goose __Anna’s Hummingbird __Pigeon Guillemot __Red-footed Booby __Scissor-tailed Flycatcher __Varied Thrush __Brewer’s Blackbird __Gr. White-fronted Goose __Costa’s Hummingbird __Long-billed Murrelet __Brandt’s Cormorant __Fork-tailed Flycatcher __Gray Catbird __Common Grackle __Taiga Bean-Goose __Calliope Hummingbird __Marbled Murrelet __Pelagic Cormorant __Olive-sided Flycatcher __Brown Thrasher __Great-tailed Grackle __Brant __Rufous Hummingbird __Kittlitz’s Murrelet __Double-crested Cormorant __Greater Pewee (s) __Sage Thrasher __Ovenbird __Cackling Goose __Allen’s Hummingbird (1894) __Scripps’s Murrelet __American White Pelican __Western Wood-Pewee __Northern Mockingbird __Northern Waterthrush __Canada Goose __Broad-tailed Hummingbird __Guadalupe Murrelet __Brown Pelican __Eastern Wood-Pewee __European Starling (I) __Golden-winged Warbler __Trumpeter Swan __Broad-billed Hummingbird __Ancient Murrelet __American Bittern __Yellow-bellied Flycatcher __Bohemian Waxwing __Blue-winged Warbler __Tundra Swan __Virginia Rail -

Kansas Raptors Third Edition ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■

A POCKET GUIDE TO Kansas Raptors Third Edition ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Text by Bob Gress and Vanessa Avara Photos by Bob Gress Funded by Westar Energy Green Team, Glenn Springs Holdings Inc., Occidental Chemical Corporation, and the Chickadee Checkoff Published by the Friends of the Great Plains Nature Center Table of Contents • Introduction • 2 • Species Accounts Vultures ■ Turkey Vulture • 4 ■ Black Vulture • 6 Osprey ■ Osprey • 8 Kites, Harriers, Eagles and Hawks ■ Mississippi Kite • 10 ■ Northern Harrier • 12 ■ Golden Eagle • 14 ■ Bald Eagle • 16 ■ Sharp-shinned Hawk • 18 ■ Cooper’s Hawk • 20 ■ Northern Goshawk • 22 Bald Eagle ■ Broad-winged Hawk • 24 ■ Red-shouldered Hawk • 26 ■ Red-tailed Hawk • 28 ■ Swainson’s Hawk • 30 ■ Rough-legged Hawk • 32 ■ Ferruginous Hawk • 34 American Kestrel Falcons ■ Cover Photo: American Kestrel • 36 Ferruginous Hawk ■ Merlin • 38 ■ Prairie Falcon • 40 ■ Peregrine Falcon • 42 ■ Gyrfalcon • 44 Barn Owl ■ Barn Owl • 46 Typical Owls ■ Eastern Screech-Owl • 48 ■ Great Horned Owl • 50 ■ Snowy Owl • 52 ■ Burrowing Owl • 54 ■ Barred Owl • 56 ■ Long-eared Owl • 58 ■ Short-eared Owl • 60 ■ Northern Saw-whet Owl • 62 Burrowing Owl • Rare Kansas Raptors • 64 ■ Swallow-tailed Kite ■ White-tailed Kite ■ Harris’s Hawk ■ Gray Hawk ■ Western Screech-Owl ■ Flammulated Owl • Falconry • 65 • The Protection of Raptors • 66 • Pocket Guides • 68 Glenn Springs Holdings, Inc. Chickadee Checkoff 1 Introduction Raptors are birds of prey. They include hawks, eagles, falcons, owls and vultures. They are primarily hunters or scavengers and feed on meat or insects. Most raptors have talons for killing their prey and a hooked beak for tearing meat. Of the 53 species of raptors found in the United States and Canada, 30 occur regularly in Kansas and an additional six species are considered rare. -

The Overwhelming Influence of Ptarmigan Abundance on Gyrfalcon Reproductive Success in the Central Yukon, Canada

THE OVERWHELMING INFLUENCE OF PTARMIGAN ABUNDANCE ON GYRFALCON REPRODUCTIVE SUCCESS IN THE CENTRAL YUKON, CANADA NormaN Barichello 1 aNd dave mossop 2 1Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada 2Northern Research Institute, Yukon College, Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada ABSTRACT .—Companion studies of Willow Ptarmigan ( Lagopus lagopus ) and Gyrfalcons ( Falco rusticolus ) in the central Yukon from 1978 to 1983 allowed us to examine Gyrfalcon reproductive performance at 14 nest sites in relation to ptarmigan abundance and other potential effects, includ - ing weather variables, the previous year’s success, nest site characteristics, and Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos ) nesting density. Ptarmigan abundance declined six-fold and was mirrored by a significant decline in Gyrfalcon breeding success (breeding failure 58%, clutch desertion 33%). Clutch size showed little variation, although deserted nests held fewer eggs than did successful nests, and there were more four-egg clutches when ptarmigan were most abundant. An average of 2.26 young fledged per nest during abundant ptarmigan years, and 0.l8 when ptarmigan were declining. No other factors were correlated with Gyrfalcon reproductive success. Juvenile ptarmi - gan density had a compensatory effect: even when ptarmigan breeding numbers dipped, Gyrfal - cons bred successfully if the proportion of juvenile ptarmigan was high. Clutch initiation date was a good predictor of Gyrfalcon breeding performance. Early clutches had more eggs (67% with 4 eggs compared to 27% in late nests), were less likely to be deserted (5% vs. 59%), and fledged more young (93% vs. 38%). Two Gyrfalcon pairs, supplemented with food in a poor ptarmigan year, fledged young at a rate and schedule comparable to pairs during a peak ptarmigan year. -

Falco Rusticolus) in Northern Fennoscandia

CONSERVATION BIOLOGY OF THE GYRFALCON (FALCO RUSTICOLUS) IN NORTHERN FENNOSCANDIA PERTTI KOSKIMIES Vanha Myllylammentie 88, FI-02400 Kirkkonummi, Finland. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT.—Northern Fennoscandia is one of the few areas in the world where there are system- atic and comparable data on the population density and breeding of the Gyrfalcon during the last 150 years. I have studied population ecology and conservation biology of the species in Finland and nearby areas on the Swedish and Norwegian side of the border since the early 1990s by searching for and monitoring all territories in a defined area. The study area is relatively flat with gently sloping fell-mountains covered by pine and birch forests, the highest tops reaching ca. 1,000 m above the sea level. Ptarmigan form almost 90% of the prey items during the breeding season, about three quarters of them being Willow Ptarmigan (Lagopus lagopus) and one quarter Rock Ptarmigan (L. muta). These two species offer almost the only available food for falcons during winter. The density of Willow Ptarmigan, the main prey species, has varied nine-fold during late winter and early spring from 2000 to 2010, and this fluctuation has had a marked effect on both the percentage of pairs starting to breed and on breeding success of the total population. Territory occupation varied markedly. Of the 25 territories surveyed every year from 2000 to 2010, 12 had breeding pairs every second year or more often, but one-quarter of them were occupied only once or twice during that study period. The median frequency of territory occupancy by a breeding pair was four in 11 years. -

Falco Rusticolus

Falco rusticolus -- Linnaeus, 1758 ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- FALCONIFORMES -- FALCONIDAE Common names: Gyrfalcon; European Red List Assessment European Red List Status LC -- Least Concern, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) EU27 regional assessment: Vulnerable (VU) In Europe this species has a very large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence <20,000 km2 combined with a declining or fluctuating range size, habitat extent/quality, or population size and a small number of locations or severe fragmentation). The population size may be small, but it is not believed to approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population size criterion (<10,000 mature individuals with a continuing decline estimated to be >10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). The population trend appears to be stable, and hence the species does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population trend criterion (>30% decline over ten years or three generations). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern in Europe. The small population size in the EU27 qualifies as Vulnerable (D1), and there is not considered to be significant potential for rescue from outside the EU27, so the final category is unchanged. Occurrence Countries/Territories of Occurrence Native: Greenland (to DK); Finland; France; Iceland; Norway; Russian Federation; Sweden Vagrant: Austria; Belgium; Czech Republic; Denmark; Estonia; Germany; Ireland, Rep. -

The Gyr Falcon in Finnmark

.NO SK /FU R G O L F E The Gyr Falcon in T O I U B R . I S W M W E Finnmark W Information sheet for the project «Bird tourism in central and eastern Finnmark», a project part of «The natural heritage as a value creator (M)» he Gyr Falcon is the world’s largest falcon. Due its hunting skills, it is one of the most Thighly valued and most sought-after birds of prey among falconers. It has a circumpolar distribution, and is the only falcon species that regularly overwinters in the Arctic. In order to survive the long and cold winter in the north, it has developed a number of special adaptations, among these a specially insulating plumage. The Gyr Falcon is distributed in mountain areas in the major part of Norway, but is most numerous in the northernmost counties. Even here it is a scarce breeding species which is seldom seen away from the nesting territory. he Gyr Falcon (Falco rusticolus) varies in colour brown upper side, and the basic colour of the underside Tfrom almost entirely white birds (Greenland) to is yellowish beige. The whole of the breast and abdomen very dark (Labrador, Canada). In Scandinavia, adult have marked streaks. The legs and cere are blue. Adult Gyr Falcons are a medium-coloured grey variant, and birds have a blue-grey upper side with paler barring only occasionally are paler birds observed. The male is and spots. The basic colour of the underside is white, the smaller, and has only about 65% of the body weight with a variable density of barring, especially on the leg of a female. -

Gyrfalcon Diet During the Brood Rearing Period on the Seward

GYRFALCON DIET DURING THE BROOD REARING PERIOD ON THE SEWARD PENINSULA, ALASKA, IN THE CONTEXT OF A CHANGING WORLD by Bryce W. Robinson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Raptor Biology Boise State University August 2016 © 2016 Bryce W. Robinson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Bryce W. Robinson Thesis Title: Gyrfalcon Diet During the Brood Rearing Period on the Seward Peninsula, Alaska, in the Context of a Changing World Date of Final Oral Examination: 19 April 2016 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Bryce W. Robinson, and they evaluated his presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. Marc J. Bechard, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee David Anderson, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Travis L. Booms, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Julie Heath, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by Marc J. Bechard, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved for the Graduate College by Jodi Chilson, M.F.A., Coordinator of Theses and Dissertations. DEDICATION To the increased understanding of the life of the Gyrfalcon, enabling its conservation and preservation for generations to come. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Undoubtedly I cannot thank everyone who deserves recognition for making this effort possible, but I will try. I have received an incredible amount of support, from the very beginning until the very end. -

210 Nielsen Layout 1

GYRFALCON POPULATION AND REPRODUCTION IN RELATION TO ROCK PTARMIGAN NUMBERS IN ICELAND ÓLAFUR K. NIELSEN Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Urriðaholtsstræti 6 –8, P.O. Box 125, 212 Garðabær, Iceland. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT.—I have studied the population ecology of the Gyrfalcon (Falco rusticolus) since 1981 on a 5,300-km2 study area in northeast Iceland harbouring 83 traditional Gyrfalcon territories. The main questions addressed relate to the predator–prey relationship of the Gyrfalcon and its main prey, the Rock Ptarmigan (Lagopus muta). Specifically, how does the Gyrfalcon respond func- tionally and numerically to changes in ptarmigan numbers? Field work involved an annual census to determine occupancy of Gyrfalcon territories, breeding success, and food. Also, Rock Ptarmi- gan were censused annually on six census plots within the study area. The Rock Ptarmigan pop- ulation showed multi-annual cycles, with peaks in 1986, 1998 and 2005. Cycle period was 11 or 12 years based on the 1981−2003 data. The Gyrfalcon in Iceland is a resident specialist predator and the Rock Ptarmigan is the main food in all years. The functional response curve was just slightly concave but ptarmigan densities never reached levels low enough to reveal the lower end of the trajectory. Occupancy rate of Gyrfalcon territories followed Rock Ptarmigan numbers with a 3−4 year time-lag. Gyrfalcons reproduced in all years, and all measures of Gyrfalcon breeding success—laying rate, success rate, mean brood size, and population productivity—were signifi- cantly related to March and April weather and to Rock Ptarmigan density. The Gyrfalcon data show characteristics suggesting that the falcon could be one of the forces driving the Rock Ptarmi- gan cycle (resident specialist predator, time-lag). -

Conservation Assessment for Northern Goshawk (Accipiter Gentilis)

DRAFT Western Great Lakes Northern Goshawk Conservation Assessment DRAFT Conservation Assessment for Northern Goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) Linnaeus in the Western Great Lakes Photo credit: Phil Detrich, USFWS USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region August 10, 2007 Dr. John Curnutt U. S. Forest Service Milwaukee, Wisconsin This document is undergoing peer review, comments welcome 1 DRAFT Western Great Lakes Northern Goshawk Conservation Assessment DRAFT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TBD ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS TBD 2 DRAFT Western Great Lakes Northern Goshawk Conservation Assessment DRAFT Table Of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................... 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 8 APPROACH , SCOPE AND METHODS OF ASSESSMENT ................................................................................. 10 THE DATA ................................................................................................................................................. 11 STRUCTURE AND LAYOUT OF THIS ASSESSMENT ...................................................................................... 11 THE GOSHAWK ...................................................................................................................................... -

Behavior of a Young Gyrfalcon

BEHAVIOROF A YOUNG GYRFALCON BY TOM J. CADE N THE course of field work supported by a grant from the Arctic Institute I of North America and the Office of Naval Research, I had an opportunity in the last week of August, 1950, to visit the Kougarok region of Seward Peninsula, Alaska. I spent the week at the Rainbow Mining Camp, owned and operated by Frank Whaley and Sterling Montague and located on the Nuxapaga River at its confluence with Boulder Creek. These men owned a pet Gyrfalcon (F&o rusticolus), which I was permitted to handle and observe during my stay at the camp. The history of this birds’ capture and treatment in captivity is about as follows. On July 4, while on an excursion up the Nuxapaga River, Mr. Mon- tague discovered a falcon aerie located on a steep bank in a bend of the river near Goose Creek. One of the parent birds, presumably the female, was shot on the nest. A single downy nestling found at the nesting site was taken back to camp and kept in a chicken-wire enclosure 3x5 feet in surface area, 3 feet high, and with an open top. Later, when the fledgling became active, a cross-bar perch was provided. Also a rag dummy was affixed to a pulley affair, by which it was jerked up and down in front of the falcon to “tease” her. (I judged the bird to be a female on the basis of size.) During the first weeks of captivity the bird was fed entirely on grayling trout and pike: and later, when she began to refuse this diet, on ground squirrels.