215 Johansen Layout 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatial Relationships of Nesting Golden Eagles in Central Utah

White, C. M. 1974. The 1974 raptor surveyof the AlaskaPipeline between Franklin Bluffsand Big Delta. Unpubl.interim rep. to U.S.Fish and Wildl. Serv.,Anchorage, AK. 10 pp. White, C. M., T. D. Ray,and L. W. Sowl.1977. The 1970-1972-1974raptor surveys alongthe Trans-AlaskaOil Pipeline.pp. 199-221.In.' Chancellor,R.D. (ed.).World Conferenceon Birdsof Prey, Reportof the Proceedings.International Council for BirdPreservation. 440 pp. + appendices. SPATIAL RELATIONSHIPS OF NESTING GOLDEN EAGLES IN CENTRAL UTAH by DwightG. Smith• BiologyDepartment SouthernConnecticut State University New Haven, Connecticut 06515 and JosephR. Murphy Departmentof Zoology BrighamYoung University Provo, Utah 84602 Abstract We examinedthe distributionof GoldenEagle (Aquila chrysaetos)nest sites in the easternGreat Basinusing the Clark-Evansnearest-neighbor method of analysis.Distri- butionvalues indicated. uniform spacing of nestsites within the hills and ridges,which providedall of the potentialnesting sites in the studyarea. Analysis of GoldenEagle nestsite distributionwith three other large raptorssuggested a tendencytoward uni- form spacingbetween diurnal raptor speciesand aggregationwith the Great Horned Owl (Bubovirginianus). Introduction Odum(1971) suggested that populationsexhibit one of threedistribution patterns: (1) random,where habitat is homogenousand individualsdo not normallyinteract; (2) uni- form,where habitat is homogenousand individualscompete for one or moreresources; (3) aggregated,that mayresult from either heterogenous habitat or a tendencyto aggre- gatesocially. Newton (1979) noted that manyspecies exhibit uniform distribution of ter- ritoriesand nest sites except where available sites are limitedand concentrated,such as in the SnakeRiver Birds of PreyNatural Area. Our observationsof GoldenEagles in the easternGreat BasinDesert revealed a concentrationof nestsites in high, north-south orientedridges and hills but nonein interveningbroad, flat valleys.Herein we examine thisdistribution using the Clark-Evansnearest-neighbor model (1954). -

Gyrfalcon Falco Rusticolus

Gyrfalcon Falco rusticolus Rob Florkiewicz surveys, this area was included. Eight eyries are known from this Characteristics and Range The northern-dwelling Gyrfalcon is part of the province; however, while up to 7 of these eyries have the largest falcon in the world. It breeds mostly along the Arctic been deemed occupied in a single year, no more than 3 have been coasts of North America, Europe and Asia (Booms et al. 2008). productive at the same time. Based on these data and other Over its range, its colour varies from white through silver-grey to sightings, the British Columbia Wildlife Branch estimates the almost black; silver-grey is the most common morph in British breeding population in the province to be fewer than 20 pairs Columbia. It nests on cliff ledges at sites that are often used for (Chutter 2008). decades and where considerable amounts of guano can accumulate. Ptarmigan provide the Gyrfalcon's main prey in In British Columbia, the Gyrfalcon nests on cliff ledges on British Columbia and productivity appears dependent on mountains in alpine areas, usually adjacent to rivers or lakes. ptarmigan numbers. Large size and hunting prowess make the Occasionally, it nests on cliffs of river banks and in abandoned Gyrfalcon a popular bird with falconers, who breed and train Golden Eagle nests. them to hunt waterfowl and other game birds. Conservation and Recommendations Whilst the Gyrfalcon is Distribution, Abundance, and Habitat Most Gyrfalcons breed designated as Not at Risk nationally by COSEWIC, it is Blue-listed along the Arctic coast; however, a few breed in the northwest in British Columbia due to its small known breeding population portion of the Northern Boreal Mountains Ecoprovince of British (British Columbia Ministry of Environment 2014). -

Natural History of the Gyrfalcon in the Central Canadian Arctic K.G

ARCTIC VOL. 41, NO. 1 (MARCH 1988) P. 31-38 Natural History of the Gyrfalcon in the Central Canadian Arctic K.G. POOLE' and R.G. BROMLEY2 (Received 24 March 1987; accepted in revised form 24 September 1987) ABSTRACT. A population of breeding gyrfalcons was studied from 1982to 1986 on 2000a km2 area in thecentral Arctic of the NorthwestTerritories. Each year 14-18 territories were occupied. The meanintemest distance was 10.6 km, giving oneof the highest recorded densitiesfor the species. There was a tendency for regularity in spacing of territories. Most (85%) nests were in abandoned stick nests of common ravens or golden eagles. Rough-legged hawk nests were not used by gyrfalcons, despite numerous available.date Mean of initiation of laying was 8 May. Meansize of clutch was 3.80 and of brood was 2.53, and mean productivity was 1SO fledged young. A reduction of 48% from estimated numberof eggs laid to number of fledglings was determined. Reproductive success declined with increased severity of spring weather, notablydays increased and amount of precipitation. Key words: gyrfalcon (Falco rusticolus),natural history, reproductive ecology, central Arctic RÉSUMÉ. Qtre 1982 et 1986, on a étudié une populationde gerfauts en reproduction dans une zone de 2000 km2dans la région centrale arctiquedes Territoires du Nord-Ouest. Quatorze des 18 aires étaient occupées chaque année. La distance entremoyenne les nids étaitde 10,6km, soit la plus grande densité relevée pour cetteespèce. Les aires avaient tendanceB être espacéesrégulitrement. La plupart des nids(85 p. cent) étaient situésdans des nids de brindilles occupés précédemment pardes corbeaux communsou des aigles dorés. -

The Occurrence and Reestablishment of White-Tailed Eagle and Golden Eagle As Breeding Birds in Denmark

The occurrence and reestablishment of White-tailed Eagle and Golden Eagle as breeding birds in Denmark Erik EhmsEn, LEnnart PEdErsEn, hans meltoftE, tschErning cLausEn & timmE nyEgaard (Med et dansk resumé: Forekomst og genetablering af Havørn og Kongeørn som danske ynglefugle) Abstract Except for a number of largely unsuccessful breeding attempts during the second half of the 20th century, the White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla had been absent as a breeding bird in Denmark for more than 80 years, when a popu- lation established itself during the second half of the 1990s. Released from persecution and contaminants the population has grown to 37 pairs in just 16 years. Reproductive success has grown with age and experience of the birds, so that the average number of fledged young per breeding pair peaked with almost two per pair 8-10 years after the establishment of each breeding pair. Similarly, the Golden Eagle Aquila chrysaetos reestablished a small population in Denmark from 1999 onwards after probably having bred here until about 150 years ago. For both species, this success was facilitated by conservation efforts including protection zones around eagle nests, monitoring and public outreach mainly carried out by volunteers from the Danish Ornithological Society / BirdLife Denmark. Introduction in former times, while the White-tailed Eagle bred in The reestablishment of White-tailed Eagle Haliaee- Denmark until it was driven extinct by persecution tus albicilla and Golden Eagle Aquila chrysaetos as in 1912 (Løppenthin 1967). The latter species made breeding birds in Denmark in the 1990s is one of a number of – usually unsuccessful – breeding at- the greatest achievements in modern Danish bird tempts during the second half of the 20th century, and nature conservation. -

Possible DRAFT Rule Language to Cover Taking Young

Attachment 3 DIVISION 55 FALCONRY LICENSES, PERMITS AND REQUIREMENTS 635-055-0000 Definition of Terms For the purpose of these rules, the following definitions apply: (1) "Captive bred" means any raptor, including eggs, hatched in captivity resulting from parents that mated in captivity, or are the progeny of artificial insemination. (2) "Falconry" is caring for and training raptors for pursuit of game, and the sport of hunting wild game with raptors. (3) “Indigenous raptor”, for purposes of falconry, means golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), sharp-shinned hawk (Accipter striatus), Cooper’s hawk (Accipter cooperii), northern goshawk (Accipter gentilis), red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis), American kestrel (Falco sparverius), merlin (Falco columbarius), prairie falcon (Falco mexicanus), peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus), gyrfalcon (Falco rusticolus, and great horned owl (Bubo virginianus), (4) “Management or operational activities” means activities on nest-site structures (bridges or buildings) that are operational or maintenance actions to the structure deemed necessary by the structure owners or managers. These activities do not include nest entries for the purposes of banding birds for scientific purposes. (4) (5) “Passage” means first year migrant raptors capable of flight. (5) (6) “Post-fledgling” means a young first-year bird capable of flight which has recently flown from its nest. (6)(7) "Raptor" means any species or hybrid of the families Strigidae, Falconidae and Accipitridae. (7)(8) “Raptors at hack” means the intentional release of a raptor as a training technique, with the expectation of recapture after a period of time. (8)(9) "Take", for the purposes of these rules, means to trap, capture, or attempt to trap or capture a raptor from the wild for the purpose of falconry. -

Predation by a Golden Eagle on a Brown Bear Cub

SHORT COMMUNICATION N Sørensen et al. Predation by a golden eagle on a brown bear cub Ole J. Sørensen1,4, Mogens Totsa˚ s2, Tore eagles attending bears. Murie hypothesized that Solstad2, and Robin Rigg3 eagles attending bears were waiting for opportunities to capture prey trying to escape from the bears. He 1North-Trondelag University College, Department of also observed eagles swooping at and diving low over Natural Resource Sciences and Information Technology, grizzlies and other carnivores, but interpreted this Box 2501, N-7729 Steinkjer, Norway behavior as play or curiosity, rather than predation. 2 Norwegian Nature Inspectorate, N-7485 Trondheim, C. McIntyre (US National Park Service, Fair- Norway 3 banks, Alaska, USA, personal communication, 2008), Slovak Wildlife Society, PO Box 72, 033 01 Liptovsky a golden eagle researcher in Denali National Park for Hradok, Slovakia many years, has never seen an eagle attack a bear, although she has often observed eagles following Abstract: During spring 2004 an adult female brown bears in open terrain, perhaps positioning themselves bear (Ursus arctos) and her 3 cubs-of-the-year were to take prey escaping from the bear as suggested by observed outside their den on a south-facing low- Murie. Commensalistic hunting, as well as curious or alpine slope in central Norway. They remained near play behavior by eagles in the vicinity of bears, could the den for 8–10 days and were, except for one day, be misinterpreted as eagles hunting, attacking, or observed daily by Totsa˚s and other wardens of the inspecting bears as possible prey. Predation by eagles Norwegian Nature Inspectorate. -

The Eagle Huntress Ancient Traditions and New Generations

1 The Eagle Huntress Ancient Traditions and New Generations By Adrienne Mayor [email protected] May 1, 2016 "The sight of a Eurasian nomad hunting with swift horse, loyal dog, and powerful golden eagle is a majestic scene with ancient roots. For thousands of years this was how the nomadic peoples of the northern steppes from the Caucasus to Manchuria hunted for survival. " This is a revised and expanded version of the two-part article that appeared April 5-6, 2016 online at ancient-origins.net and reprinted April 18, 2016 http://bust.com/feminism/16147-the-untold-history-of-the-eagle-huntress.html "A fast horse and a soaring eagle are the wings of a nomad." --Kazakh proverb 2 FIG 1. Kazakh eagle hunter (Shutterstock) Falconry, training raptors to hunt for game, is particularly suited to vast grasslands especially in combination with horses and dogs. The earliest images of falconry appear in Assyrian and Hittite reliefs of the 9th and 8th centuries BC. Classical Greek and Roman authors Ctesias, Aristotle, Pliny, and Aelian described falconry. A Persian textile (10th century AD) depicts the Banu (Lady Governor) of Rayy (ancient Rhages, near Tehran, northern Iran) riding with her falcon. In AD 1270 Marco Polo described how the nomads of Central Asia hunted on horseback with small falcons, hawks, and eagles. FIG 2. Banu (Lady Governor) of Rayy, Persian textile, 10th century AD 3 For thousands of years, golden eagles have been the favorite raptor to train as a hunting companion across the northern steppes from the Caucasus to China. Eagles are strong predators especially adapted to winter hunting for hare, marmot, wild goat, deer, fox (even lynx, pallas cat, and wolf, although these are unnatural prey and dangerous for the eagles). -

Golden Eagle

A publication by: NORTHWEST WILDLIFE PRESERVATION SOCIETY Golden Eagle Aquila chrysaetos Photograph by Jim Crotty (Flickr) By Jennifer Chow The golden eagle is the largest bird-of-prey in North America, and one of only two eagle species in Canada along with the bald eagle. They are graceful, powerful, swift and agile raptors. Some regard the golden eagle as one of the most formidable birds on Earth. Sightings of this beautiful raptor are rare, but always exciting and memorable. Golden eagles are symbols of freedom and majesty throughout their range. NWPS Headquarters NWPS Vancouver Island t Vancouver 604.568.9160 720-1190 Melville Street PO Box 39058 t Victoria 778.967.3379 Vancouver, BC V6E 3W1 RPO James Bay e [email protected] Victoria, BC V8V 4X8 w www.northwestwildlife.com Characteristics Golden Eagles are dark brown with golden-brown feathers on their head and necks, giving them their namesake; with yellow feet, black claws and beak, and feathers going all the way down to the toes, they are truly an impressive sight. They are large birds measuring 70 to 84cm (28 to 33 inches) in height with a 210 cm (84 in) wingspan. Females are typically larger than males, with females weighing 5 kg (11 lbs) and males slightly less. Other than the size difference, males and females look alike. Their feathers actually weigh more than their bones and golden eagles can have around 7,000 feathers! Very young chicks are covered in a white down, with dark feathers as they grow in. Young golden eagles have defined white patches at the tail base and in the wings for the first few years. -

WBRC Review List 2020

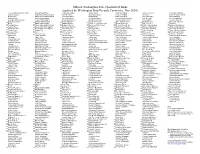

Official Washington State Checklist of Birds (updated by Washington Bird Records Committee, Nov 2020) __Fulvous Whistling-Duck (1905) __White-throated Swift __Long-tailed Jaeger __Nazca Booby __Tropical Kingbird __Dusky Thrush (s) __Tricolored Blackbird __Emperor Goose __Ruby-throated Hummingbird __Common Murre __Blue-footed Booby __Western Kingbird __Redwing __Brown-headed Cowbird __Snow Goose __Black-chinned Hummingbird __Thick-billed Murre __Brown Booby __Eastern Kingbird __American Robin __Rusty Blackbird __Ross’s Goose __Anna’s Hummingbird __Pigeon Guillemot __Red-footed Booby __Scissor-tailed Flycatcher __Varied Thrush __Brewer’s Blackbird __Gr. White-fronted Goose __Costa’s Hummingbird __Long-billed Murrelet __Brandt’s Cormorant __Fork-tailed Flycatcher __Gray Catbird __Common Grackle __Taiga Bean-Goose __Calliope Hummingbird __Marbled Murrelet __Pelagic Cormorant __Olive-sided Flycatcher __Brown Thrasher __Great-tailed Grackle __Brant __Rufous Hummingbird __Kittlitz’s Murrelet __Double-crested Cormorant __Greater Pewee (s) __Sage Thrasher __Ovenbird __Cackling Goose __Allen’s Hummingbird (1894) __Scripps’s Murrelet __American White Pelican __Western Wood-Pewee __Northern Mockingbird __Northern Waterthrush __Canada Goose __Broad-tailed Hummingbird __Guadalupe Murrelet __Brown Pelican __Eastern Wood-Pewee __European Starling (I) __Golden-winged Warbler __Trumpeter Swan __Broad-billed Hummingbird __Ancient Murrelet __American Bittern __Yellow-bellied Flycatcher __Bohemian Waxwing __Blue-winged Warbler __Tundra Swan __Virginia Rail -

Pocket Guide to Raptors of the Pembina Valley Region, Manitoba

A POCKET FIELD GUIDE TO RAPTORS OF THE PEMBINA VALLEY REGION www.arocha.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements . 3 Introduction . 4 Osprey About raptors . 5 Vulture Osprey How to use this guide . 6 Turkey Vulture Glossary . 7 Vultures (Turkey Vulture) . 9 Osprey . 11 Eagles . 13 Harrier Bald Eagle . 13 Northern Harrier Golden Eagle . 15 Harriers (Northern Harrier) . 17 Eagle Accipiters . 19 Bald Eagle Sharp-shinned Hawk . 19 Golden Eagle Cooper’s Hawk . 21 Northern Goshawk . 23 Accipiter Buteos . 25 Sharp-shinned Hawk Broad-winged Hawk . 25 Cooper’s Hawk Swainson’s Hawk . 26 Northern Goshawk Red-tailed Hawk . 27 Rough-legged Hawk . 31 Falcons . 33 Falcon Buteo American Kestrel . 33 American Kestrel Broad-winged Hawk Merlin Swainson’s Hawk Merlin . 35 Gyrfalcon Red-tailed Hawk Peregrine Falcon . 37 Peregrine Falcon Ferruginous Hawk Rare raptors in the Pembina Valley Region . 39 Rough-legged Hawk Check-list of raptors . 40 Bibliography . 41 1 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS INTRODUCTION Funding for this pocket guide was provided by Birds of prey have fascinated people through the the Canadian Wildlife Federation, Manitoba ages. They have appeared in the courts of kings, Tourism Secretariat and A Rocha donors. Special on the arms of falconers and have been studied thanks goes to the following people who by many biologists and scientists. For anyone provided photographs: Alfred Aug, Vic Berardi, who has grown up on the prairies, the lazy Gordon Court, Jerry Liguori, Bob Shettler, Phil circling of a hawk on a warm summer day is an Swanson, Dennis Swayze, Robert Visconti and iconic memory. Historically persecuted for their Brian Wheeler. -

Golden Eagle (Aquila Chrysaetos)

Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) NMPIF level: Biodiversity Conservation Concern, Level 2 (BC2) NMPIF assessment score: 12 NM stewardship responsibility: Low National PIF status: No special status New Mexico BCRs: 16, 18, 34, 35 Primary breeding habitat(s): Cave/Rock/Cliff (often mountain canyons near open grassland or shrubland) Other Habitats used: Widespread foraging across multiple habitat types Summary of Concern Golden Eagle is a widespread raptor of Europe, Asia, and North America. Although trends appear stable, this species is vulnerable due to its relatively small population size and various sources of mortality, including habitat loss or degradation. Associated Species Ferruginous Hawk (SC1), Red-tailed Hawk, Peregrine Falcon (BC1), Prairie Falcon (SC2), White-throated Swift (SC2), Common Raven Distribution Golden Eagles breed across a great range of latitudes in North America, from the Brooks Range in Alaska south to central Mexico. The species also breeds in Europe and Asia. In the United States, Golden Eagle is resident in all western states, with a breeding range extending east into the Great Plains. United States populations increase in winter with the arrival of migrants from northern breeding areas. In New Mexico, Golden Eagles breed locally in suitable habitat throughout the state (Kochert et al. 2002, Parmeter et al. 2002). Ecology and Habitat Requirements During the breeding season, Golden Eagle occurs primarily in areas of mountain cliffs or canyons. In the west, it is often associated with rimrock terrain adjacent to open desert or grassland areas. Suitable nesting sites may exist within a variety of surrounding habitats, from desert to mountain areas, although dense forests tend to be avoided. -

BEAR CART the Following Items Should Be on the Cart, If They Are Not

BEAR CART The following items should be on the cart, if they are not let someone in education know. If you discover a new problem with any biofact (broken pieces, loose teeth, etc.), it is your responsibility to let the staff know and make a notation with the date, time and your name on the sign out clipboard. Note: Please return all items to their appropriate place on the cart, and make sure lids and bungee cords are secured. Things should be left exactly as you found them. Note: Do not try to open the Lucite containers with the food. We are trying to prevent animals from getting into the bone room. BEAR CART INVENTORY • Black Bear skull • Kodiak Bear skull • Kodiak Bear front leg including the scapula, humerus, radius, and ulna (see note below) • Kodiak Bear paw with claws • Black Bear, Polar Bear & Lion claw • Kodiak Bear pelt • Box of Bear’s Bile Powder - Traditional Chinese medicine (DO NOT OPEN BOX!!) • 2 lucite boxes containing grizzly bear and polar bear food • Golden Eagle egg • Golden Eagle leg/foot • Bears Resource Notebook Note: You will need large piece of AstroTurf if you intend to use the leg bones. Please do not place bones directly on the ground. Lay the bones on the AstroTurf starting with the humerus at the top; visitors can then lie down next to them to see how tall they are in relation to an adult male Kodiak bear. Remember this “shoulder” height is with the bear standing on all four legs. Do not let the public pick up the bones, they are heavy.