The Gyr Falcon in Finnmark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gyrfalcon Falco Rusticolus

Gyrfalcon Falco rusticolus Rob Florkiewicz surveys, this area was included. Eight eyries are known from this Characteristics and Range The northern-dwelling Gyrfalcon is part of the province; however, while up to 7 of these eyries have the largest falcon in the world. It breeds mostly along the Arctic been deemed occupied in a single year, no more than 3 have been coasts of North America, Europe and Asia (Booms et al. 2008). productive at the same time. Based on these data and other Over its range, its colour varies from white through silver-grey to sightings, the British Columbia Wildlife Branch estimates the almost black; silver-grey is the most common morph in British breeding population in the province to be fewer than 20 pairs Columbia. It nests on cliff ledges at sites that are often used for (Chutter 2008). decades and where considerable amounts of guano can accumulate. Ptarmigan provide the Gyrfalcon's main prey in In British Columbia, the Gyrfalcon nests on cliff ledges on British Columbia and productivity appears dependent on mountains in alpine areas, usually adjacent to rivers or lakes. ptarmigan numbers. Large size and hunting prowess make the Occasionally, it nests on cliffs of river banks and in abandoned Gyrfalcon a popular bird with falconers, who breed and train Golden Eagle nests. them to hunt waterfowl and other game birds. Conservation and Recommendations Whilst the Gyrfalcon is Distribution, Abundance, and Habitat Most Gyrfalcons breed designated as Not at Risk nationally by COSEWIC, it is Blue-listed along the Arctic coast; however, a few breed in the northwest in British Columbia due to its small known breeding population portion of the Northern Boreal Mountains Ecoprovince of British (British Columbia Ministry of Environment 2014). -

Strong Degradation of Palsas and Peat Plateaus in Northern Norway During the Last 60 Years

Strong degradation of palsas and peat plateaus in northern Norway during the last 60 years A. F. Borge, S. Westermann, I. Solheim, B. Etzelmüller Department of Geosciences, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1047, 0316 Oslo, Norway 5 Correspondence to: S. Westermann ([email protected]) Abstract. Palsas and peat plateaus are permafrost landforms occurring in subarctic mires which constitute sensitive ecosystems with strong significance for vegetation, wildlife, hydrology and carbon cycle. We have systematically mapped the occurrence of palsas and peat plateaus in the northernmost county of Norway (Finnmark, ~50,000 km2) by manual interpretation of aerial images from 2005-2014 at a spatial resolution of 250 m2. At this resolution, mires and wetlands with 10 palsas or peat plateaus occur in about 850 km2 of Finnmark, with the actual palsas and peat plateaus underlain by permafrost covering a surface area of approximately 110 km2. Secondly, we have quantified the lateral changes of the extent of palsas and peat plateaus for four study areas located along a NW-SE transect through Finnmark by utilizing repeat aerial imagery from the 1950s to the 2010s. The results of the lateral changes reveal a total decrease of 33-71 % in the areal extent of palsas and peat plateaus during the study period, with the largest lateral change rates observed in the last decade. However, the 15 results indicate that degradation of palsas and peat plateaus in northern Norway has been a consistent process during the second half of the 20th century and possibly even earlier. Significant rates of areal change are observed in all investigated time periods since the 1950s, and thermokarst landforms observed on aerial images from the 1950s suggest that lateral degradation was already an ongoing process at this time. -

Natural History of the Gyrfalcon in the Central Canadian Arctic K.G

ARCTIC VOL. 41, NO. 1 (MARCH 1988) P. 31-38 Natural History of the Gyrfalcon in the Central Canadian Arctic K.G. POOLE' and R.G. BROMLEY2 (Received 24 March 1987; accepted in revised form 24 September 1987) ABSTRACT. A population of breeding gyrfalcons was studied from 1982to 1986 on 2000a km2 area in thecentral Arctic of the NorthwestTerritories. Each year 14-18 territories were occupied. The meanintemest distance was 10.6 km, giving oneof the highest recorded densitiesfor the species. There was a tendency for regularity in spacing of territories. Most (85%) nests were in abandoned stick nests of common ravens or golden eagles. Rough-legged hawk nests were not used by gyrfalcons, despite numerous available.date Mean of initiation of laying was 8 May. Meansize of clutch was 3.80 and of brood was 2.53, and mean productivity was 1SO fledged young. A reduction of 48% from estimated numberof eggs laid to number of fledglings was determined. Reproductive success declined with increased severity of spring weather, notablydays increased and amount of precipitation. Key words: gyrfalcon (Falco rusticolus),natural history, reproductive ecology, central Arctic RÉSUMÉ. Qtre 1982 et 1986, on a étudié une populationde gerfauts en reproduction dans une zone de 2000 km2dans la région centrale arctiquedes Territoires du Nord-Ouest. Quatorze des 18 aires étaient occupées chaque année. La distance entremoyenne les nids étaitde 10,6km, soit la plus grande densité relevée pour cetteespèce. Les aires avaient tendanceB être espacéesrégulitrement. La plupart des nids(85 p. cent) étaient situésdans des nids de brindilles occupés précédemment pardes corbeaux communsou des aigles dorés. -

AIP 020: Summer in Finnmark

Activities in Alta SUMMER TOURS AIP 020: Summer in Finnmark Location: Alta, Norway, plus day tours around in Finnmark County Airport: Arrive and depart Alta (ALF) Duration: 5 nights, 6 days Minimum/Maximum 2 – 4 people Clothing and gear: Be prepared for anything in the arctic summertime – rain coat and trousers, sweaters for cool weather, plus t-shirts and shorts in case of warm weather. Sturdy shoes that can get wet and dirty, for hiking. Your Tour Many people think of the arctic as a winter play paradise – snowmobiles and dogsleds, skis and fatbikes to take you along trails under the northern lights. We do have that in the winter, but the land of the midnight sun is a fantastic destination in summertime as well. Even though the snowmobiles are safely in their summer storage, there is plenty of fun activities, and lots to see as well. On this tour, you’ll get a balanced sampling of activity and sightseeing as you see the countryside around Alta and then take some time to explore other destinations like North Cape, a half-day’s journey to the northern edge of the country. Your Itinerary Day 1: Welcome to Alta! You’ll be met in the afternoon by a North Adventure representative at the airport to ensure that everything is in order with your arrival. Once you collect your luggage, you will head out by taxi to Trasti & Trine, a husky dog kennel and guest house approximately 20 minutes outside of Alta. You’ll check in and get acquainted with your delightful surroundings out in the forest. -

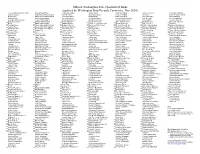

WBRC Review List 2020

Official Washington State Checklist of Birds (updated by Washington Bird Records Committee, Nov 2020) __Fulvous Whistling-Duck (1905) __White-throated Swift __Long-tailed Jaeger __Nazca Booby __Tropical Kingbird __Dusky Thrush (s) __Tricolored Blackbird __Emperor Goose __Ruby-throated Hummingbird __Common Murre __Blue-footed Booby __Western Kingbird __Redwing __Brown-headed Cowbird __Snow Goose __Black-chinned Hummingbird __Thick-billed Murre __Brown Booby __Eastern Kingbird __American Robin __Rusty Blackbird __Ross’s Goose __Anna’s Hummingbird __Pigeon Guillemot __Red-footed Booby __Scissor-tailed Flycatcher __Varied Thrush __Brewer’s Blackbird __Gr. White-fronted Goose __Costa’s Hummingbird __Long-billed Murrelet __Brandt’s Cormorant __Fork-tailed Flycatcher __Gray Catbird __Common Grackle __Taiga Bean-Goose __Calliope Hummingbird __Marbled Murrelet __Pelagic Cormorant __Olive-sided Flycatcher __Brown Thrasher __Great-tailed Grackle __Brant __Rufous Hummingbird __Kittlitz’s Murrelet __Double-crested Cormorant __Greater Pewee (s) __Sage Thrasher __Ovenbird __Cackling Goose __Allen’s Hummingbird (1894) __Scripps’s Murrelet __American White Pelican __Western Wood-Pewee __Northern Mockingbird __Northern Waterthrush __Canada Goose __Broad-tailed Hummingbird __Guadalupe Murrelet __Brown Pelican __Eastern Wood-Pewee __European Starling (I) __Golden-winged Warbler __Trumpeter Swan __Broad-billed Hummingbird __Ancient Murrelet __American Bittern __Yellow-bellied Flycatcher __Bohemian Waxwing __Blue-winged Warbler __Tundra Swan __Virginia Rail -

The Know Norwaybook

International and Comparative Studies in Education and Public Information Norway is a country of winter darkness and midnight sun, advanced technology, small towns and a few cities. It has a big The Know NORWAY Book government sector, free education and Background for Understanding the Country and Its People health services, and a modern and dynamic private sector. Pakistan and Afghanistan Edition Norway is home to large communities of Pakistani, Afghan and other immigrants and refugees. Norway is one of the world’s richest and most egalitarian societies. The country’s beauty has made tourism a major income-earner, and fishing, shipping and shipbuilding industries are still important. In the last generation, North Sea oil and gas production has made Norway one of the world’s largest oil exporters – and the Norwegians are now nicknamed “the blue-eyed sheikhs”. PRINTED IN PAKISTAN Mr.Books Atle Hetland Mr.Books Sang-e-Meel Sang-e-Meel The Know NORWAY Book Background for Understanding the Country and Its People Pakistan and Afghanistan Edition Atle Hetland Published in 2010 by Mr. Books Publishers and Booksellers, Islamabad, Pakistan www.mrbook.com.pk ISBN 969-516-166-9 This book, or part thereof, may not be reproduced in print or electronlic form without the permission from the author. Sections may, however, be reproduced for internal use by educational and research institutions and organizations, with reference given to the book. Copyright © Atle Hetland 2010 All rights reserved Author: Atle Hetland English Language and Editorial Consultant: Fiona Torrens-Spence Graphic Artist and Design: Salman Beenish Views expressed and analyses in this publication are those of the author. -

Precambrian Stratigraphy in the Masi Area, Southwestern Finnmark, Norway

Precambrian Stratigraphy in the Masi Area, Southwestern Finnmark, Norway ARNE SOLLI Solli, A. 1983: Precambrian stratigraphy in the Masi area, southwestern Finnmark, Norway. Norges geol. Unders. 380, 97-105. The rocks in the Masi areaconsistsof acomformable stratigraphicsequencecontain ing three formations. The lowest is the Gål'denvarri formation, mainly containing metamorphic basic volcanics. Above this is the Masi Quartzite with a conglomerate at its base. The upper formation in the Masi area is the Suoluvuobmi formation containing metamorphic basic volcanics, metagabbros, mica schist, graphitic schist and albite fels. The eastern part of the area is dominated by granites which have an intrusive relationship to all three formations. Remnants of the Archean basement situated further to the east probably occur within the younger granites. Nothing conclusive can be said about the ages of the rocks, but for the Gål'denvarri formation an Archean age is considered most probable. The ages of the Meisi Quartzite and Suoluvuobmi formation may be Svecokarelian, but based on correlation with rocks in Finland, Archean ages also seem likely for these units. A. Solli, Norges geologiske undersokelse, P.0.80x 3006, N-7001 Trondheim, Norway. Introduction The central part of Finnmarksvidda is occupied by a dome structure of Archean granitic gneisses (Fig. 1). On each side of the dome are supracrustal rocks. To the east is the Karasjok region, and to the west is the Kautokeino- Masi region with the same types of rocks even though no direct correlation has yet been established between the two regions. Greenstones, quartzites and mica schist are the dominating rock types. A brief summary of the geo logy of Finnmarksvidda is given by Skålvoll (1978), and Fig. -

Geochronology of the Palaeoproterozoic Kautokeino Greenstone Belt, Finnmark, Norway: Tectonic Implications in a Fennoscandia Context

NORWEGIAN JOURNAL OF GEOLOGY Vol 95 Nr. 3–4 (2015) http://dx.doi.org/10.17850/njg95-3-09 Geochronology of the Palaeoproterozoic Kautokeino Greenstone Belt, Finnmark, Norway: Tectonic implications in a Fennoscandia context Bernard Bingen1,2, Arne Solli1, Giulio Viola1,3, Espen Torgersen1, Jan Sverre Sandstad1, Martin J. Whitehouse4, Torkil S. Røhr1, Morgan Ganerød1 & Aziz Nasuti1 1Geological Survey of Norway, PO Box 6315 Sluppen, 7491 Trondheim, Norway. 2Departement of Geology, University of Liège, 4000, Liège, Belgium. 3Department of Geology and Mineral Resources Engineering, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 7491, Trondheim, Norway. 4Swedish Museum of Natural History, 104 05, Stockholm, Sweden. E-mail corresponding author (Bernard Bingen): [email protected] Zircon U–Pb geochronological data in 18 samples from Finnmarksvidda and one sample from the Repparfjord Tectonic Window, northern Norway, constrain the evolution of the Palaeoproterozoic Kautokeino Greenstone Belt and neighbouring units in a Fennoscandia context. The Jergul Complex is an Archaean cratonic block of Karelian affinity, made of variably gneissic, tonalite–trondhjemite–granodiorite–granite plutonic rocks formed between 2975 ± 10 and 2776 ± 6 Ma. It is associated with the Archaean Goldenvárri greenstone–schist formation. At the base of the Kautokeino Greenstone Belt, the Masi Formation is a typical Jatulian quartzite, hosting a Haaskalehto-type, albite–magnetite-rich, mafic sill dated at 2220 ± 7 Ma. The Likčá and Čáskejas formations represent the main event of basaltic magmatism. A synvolcanic metagabbro dates this magmatism at 2137 ± 5 Ma. The geochemical and Nd isotopic signature of the Čáskejas Formation (eNd = +2.2 ± 1.7) is remarkably similar to coeval dykes intruding the Archaean Karelian Craton in Finland and Russia (eNd = +2.5 ± 1.0). -

Climate in Norway 2100 Report

M-741 | 2017 Climate in Norway 2100 – a knowledge base for climate adaptation NCCS report no. 1/2017 Photo: Anne Olsen-Ryum, www.hasvikfoto.no Lead authors I. Hanssen-Bauer, E.J. Førland, I. Haddeland, H. Hisdal, S. Mayer, A. Nesje, J.E.Ø. Nilsen, S. Sandven, A.B. Sandø, A. Sorteberg og B. Ådlandsvik CLIMATE IN NORWAY 2100 Commissioned by The Norwegian Centre for Climate Services (NCCS) is a collaboration between the Norwegian Meteoro- logical Institute, the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate, Uni Research and the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research. The main purpose of NCCS is to provide decision makers in Norway with relevant information regarding climate change adaptation. In addition to the partners, the Norwegian Environment Agency is represented on the Board. The NCCS report series includes reports where one or more authors are affiliated to the Centre, as well as reports initiated by the Centre. All reports in the series have undergone a professional assessment by at least one expert associated with the Centre. They may also be included in report series from the institutions to which the authors are affiliated. 2 CLIMATE IN NORWAY 2100 Title: Date Climate in Norway 2100 April 2017 – a knowledge base for climate adaptation ISSN nr. Rapport nr. 2387-3027 1/2017 Authors Classification Lead authors: I.Hanssen-Bauer1,8, E.J.Førland1,8, I.Hadde- Free land2,8, H.Hisdal2,8, D.Lawrence2,8, S.Mayer3,8,9, A.Nesje4,9, J.E.Ø.Nilsen5,9, S.Sandven5,9, A.B.Sandø6,9, A.Sorteberg4,9, B.Ådlandsvik 6,9 Clients Norwegian Environment -

Where Do the Treeless Tundra Areas of Northern Highlands

Where do the treeless tundra areas of northern highlands fit in the global biome system: toward an ecologically natural subdivision of the tundra biome Risto Virtanen1, Lauri Oksanen2,3, Tarja Oksanen2,3, Juval Cohen4, Bruce C. Forbes5, Bernt Johansen6, Jukka Kayhk€ o€7, Johan Olofsson8, Jouni Pulliainen4 & Hans Tømmervik9 1Department of Ecology, University of Oulu, FI-90014 Oulu, Finland 2Department of Arctic and Marine Biology, University of Tromsø – The Arctic University of Norway, Campus Alta, NO-9509 Alta, Norway 3Section of Ecology, Department of Biology, University of Turku, FI-20014 Turku, Finland 4Finnish Meteorological Institute, PL 503, 00101 Helsinki, Finland 5Arctic Centre, University of Lapland, P.O. Box 122, FI-96101 Rovaniemi, Finland 6Northern Research Institute, Box 6434, Forskningsparken, NO-9294 Tromsø, Norway 7Department of Geography and Geology, Division of Geography, University of Turku, FI-20014 Turku, Finland 8Department of Ecology and Environmental Science, Umea University, SE-901 87 Umea, Sweden 9The Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA), Framsenteret, NO-9296 Tromsø, Norway Keywords Abstract Alpine, arctic, biome delimitation, ecoregion, mountains, tundra ecosystems, vegetation According to some treatises, arctic and alpine sub-biomes are ecologically simi- pattern, winter climate. lar, whereas others find them highly dissimilar. Most peculiarly, large areas of northern tundra highlands fall outside of the two recent subdivisions of the tun- Correspondence dra biome. We seek an ecologically natural resolution -

2 Climate and Streamflow Variability in the Tana River

2 CLIMATEANDSTREAMFLOWVARIABILITY INTHETANARIVERBASIN 2.1 Introduction Changesinclimatewillultimatelyaffectriverrunoff.Sincethelasticeageclimatein NorthernFennoscandiahasfluctuatedconsiderably.Paleoecologicalevidencesuggests thatduringthemidHolocene(ca.8000-5000BP)summerswerewarmeranddrierthan today(Seppä&Hammarlund,2000).Thereappearstobeageneralcoolingtrend throughouttherestoftheHolocene,uptothe20thcentury(Eronen&Zetterberg,1996; Seppä&Birks,2002).DirectmeasurementsonclimateanddischargeinNorthern Fennoscandiaare,however,onlyavailableforthelastcentury.Leeetal.(2000)analysed dataontemperatureandprecipitationfornorthernLapland,andconcludedthata significantwarmingoccurredinthefirsthalfofthe20thcentury,whileannual precipitationhasincreasedsince1880.Fewstudieshaveanalysedlong-termtrendsin riverdischargefornorthernLapland.Hyvärinen&Leppäjärvi(1989)analysed observationsondischargeinFinland,butcouldnotfindacleartrendforriversin northernLapland.Roaldetal.(1997)reportedaslight,thoughnotsignificant,decreasing trendforriversinnorthernFinland,SwedenandnortheastNorwayovertheperiod1930- 1980.Inthischapter,dataseriesoftemperature,precipitationandriverdischargeinthe TanaBasinareanalysed,inordertoidentifythevariationsinclimateandhydrologythat occurredoverthepastcentury.Thisanalysisisprecededbyageneraldescriptionofthe studyarea. 2.2 Studyarea 2.2.1 Location TheTanaRiverBasinislocatedinthenorthernmostpartofFennoscandia(i.e. ScandinaviaandFinland,seefigure2.1),between68º28'and70º28'Nand23º30'and 28º30'E.Thecatchmentareaisapproximately16000km2,ofwhich32%belongsto -

Complexity in Effects of Climate Change; an Example from Treeline Areas in Northernmost Europe

Central JSM Environmental Science & Ecology Bringing Excellence in Open Access Short Communication *Corresponding author Wielgolaski FE, Department of Bioscience, University of Oslo, POB 1066 Blindern, 0316 Oslo, Norway, Email: Complexity in Effects of Climate Submitted: 14 September, 2017 Change; an Example from Accepted: 04 November, 2017 Published: 08 November, 2017 ISSN: 2333-7141 Treeline Areas in Northernmost Copyright © 2017 Wielgolaski Europe OPEN ACCESS Wielgolaski FE* Keywords Department of Bioscience, University of Oslo, Norway • Semi-domesticated reindeer herding • Lichen heaths • Mountain birch Abstract • Climate change This short communication shows an example from northernmost Europe of possible cascading effects of land use and climate changes. It is suggested that complexities of effects may be common also in other biomes and thus important both for man and all biology in general. INTRODUCTION particularly during Spring, in the northern most county Finnmark (at about 70°N) since 1900 [10]. That region is also projected to Background get the highest temperature increment further to the next century The rock conditions of northernmost Europe are complex [1], throughout all seasons, but particularly during the coldest part of mainly with Precambrian, normally “acid” and poor gneisses and the year. granites east of the Caledonian north-south mountain chain. In Precipitation is generally low in the inner parts of northern northern Fennoscandia podzolic soils are well developed in the Fennoscandia, down to below 400 mm per year in some places forests, but the raw humus and bleaching layers become thinner [11], but has had an increasing trend during the whole year in in the upper treeline. These acid soils contain only small amounts the last 100 years.