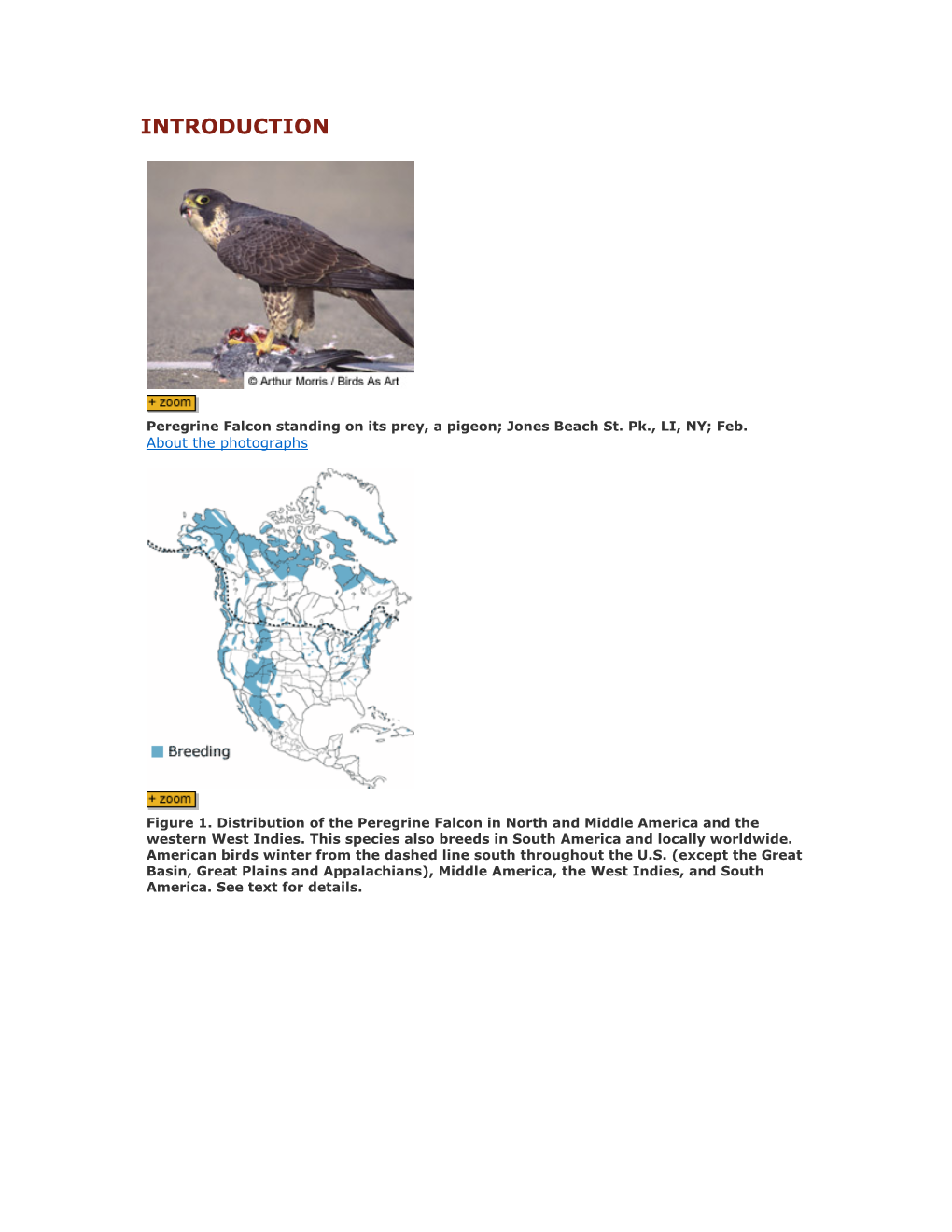

Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gyrfalcon Falco Rusticolus

Gyrfalcon Falco rusticolus Rob Florkiewicz surveys, this area was included. Eight eyries are known from this Characteristics and Range The northern-dwelling Gyrfalcon is part of the province; however, while up to 7 of these eyries have the largest falcon in the world. It breeds mostly along the Arctic been deemed occupied in a single year, no more than 3 have been coasts of North America, Europe and Asia (Booms et al. 2008). productive at the same time. Based on these data and other Over its range, its colour varies from white through silver-grey to sightings, the British Columbia Wildlife Branch estimates the almost black; silver-grey is the most common morph in British breeding population in the province to be fewer than 20 pairs Columbia. It nests on cliff ledges at sites that are often used for (Chutter 2008). decades and where considerable amounts of guano can accumulate. Ptarmigan provide the Gyrfalcon's main prey in In British Columbia, the Gyrfalcon nests on cliff ledges on British Columbia and productivity appears dependent on mountains in alpine areas, usually adjacent to rivers or lakes. ptarmigan numbers. Large size and hunting prowess make the Occasionally, it nests on cliffs of river banks and in abandoned Gyrfalcon a popular bird with falconers, who breed and train Golden Eagle nests. them to hunt waterfowl and other game birds. Conservation and Recommendations Whilst the Gyrfalcon is Distribution, Abundance, and Habitat Most Gyrfalcons breed designated as Not at Risk nationally by COSEWIC, it is Blue-listed along the Arctic coast; however, a few breed in the northwest in British Columbia due to its small known breeding population portion of the Northern Boreal Mountains Ecoprovince of British (British Columbia Ministry of Environment 2014). -

First Occurrence of Black-Chinned Hummingbird in Alabama

RARE OCCURRENCE First occurrence of Black-chinned Bummingbirdin Alabama With notes on identification Greg D. Jackson Photo/GregD. Jackson. 178 AmericanBirds, Summer 1988 observeddunng the courseof the hum- taft-pumpingof the Black-ch•nned•s b•rd (ArchtlochusalexandrO has m•ngb•rd'sstay. The b•rd wasthe same very noticeable whfie feeding, and •s beenHEBLACK-CHINNEDreported casually from HUMMING- Florida sizeas a Ruby-throated Hummingbird. generallymore frequentand persistent (Hoffman 1983)and is an annualvisitor The bill waslonger than that of a Ruby- than that shownby the Ruby-throated to southeasternLouisiana (N. L. New- throated. The wingswere pointed, but Hummingbird (N. L. Newfield pers field pers. comm.), but until January the outermostprimary had an obtuse comm.). Immature males of either spe- 1984 had never been recorded in Ala- subterminal angulation and a broad, ciescan showsome characteristic gorget bama. Besides the breeding Ruby- blunt tip. The tail, which was pumped colorby early fall (Scott 1983). throated Hummingbird (Archilochus constantlywhile feeding,had a mod- colubris),the only other member of this eratelydeep central notch when folded, family recordedin Alabamais the Ru- and was rather square with a shallow fousHummingbird (Selasphorus rufus), notch when spread.The crown and face which is a rare visitorin migrationand weredark gray-green.There wasa short w•nter (Imhof 1976). The first docu- white stripe posterior to the eye. The mented occurrence of the Black- dorsal surface of the tail showed black ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ch•nned Hummingbird in the state is outer rectrices and dark green inner from the Spring Hill district of Mobile rectrices.The remainder of the upper- The author is grateful to Nancy L. -

Patterns of Co-Occurrence in Woodpeckers and Nocturnal Cavity-Nesting Owls Within an Idaho Forest

VOLUME 13, ISSUE 1, ARTICLE 18 Scholer, M. N., M. Leu, and J. R. Belthoff. 2018. Patterns of co-occurrence in woodpeckers and nocturnal cavity-nesting owls within an Idaho forest. Avian Conservation and Ecology 13(1):18. https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-01209-130118 Copyright © 2018 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Research Paper Patterns of co-occurrence in woodpeckers and nocturnal cavity- nesting owls within an Idaho forest Micah N. Scholer 1, Matthias Leu 2 and James R. Belthoff 1 1Department of Biological Sciences and Raptor Research Center, Boise State University, Boise, Idaho, USA, 2Biology Department, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia, USA ABSTRACT. Few studies have examined the patterns of co-occurrence between diurnal birds such as woodpeckers and nocturnal birds such as owls, which they may facilitate. Flammulated Owls (Psiloscops flammeolus) and Northern Saw-whet Owls (Aegolius acadicus) are nocturnal, secondary cavity-nesting birds that inhabit forests. For nesting and roosting, both species require natural cavities or, more commonly, those that woodpeckers create. Using day and nighttime broadcast surveys (n = 150 locations) in the Rocky Mountain biogeographic region of Idaho, USA, we surveyed for owls and woodpeckers to assess patterns of co-occurrence and evaluated the hypothesis that forest owls and woodpeckers co-occurred more frequently than expected by chance because of the facilitative nature of their biological interaction. We also examined co-occurrence patterns between owl species to understand their possible competitive interactions. Finally, to assess whether co-occurrence patterns arose because of species interactions or selection of similar habitat types, we used canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) to examine habitat associations within this cavity-nesting bird community. -

Wildlife of the North Hills: Birds, Animals, Butterflies

Wildlife of the North Hills: Birds, Animals, Butterflies Oakland, California 2005 About this Booklet The idea for this booklet grew out of a suggestion from Anne Seasons, President of the North Hills Phoenix Association, that I compile pictures of local birds in a form that could be made available to residents of the north hills. I expanded on that idea to include other local wildlife. For purposes of this booklet, the “North Hills” is defined as that area on the Berkeley/Oakland border bounded by Claremont Avenue on the north, Tunnel Road on the south, Grizzly Peak Blvd. on the east, and Domingo Avenue on the west. The species shown here are observed, heard or tracked with some regularity in this area. The lists are not a complete record of species found: more than 50 additional bird species have been observed here, smaller rodents were included without visual verification, and the compiler lacks the training to identify reptiles, bats or additional butterflies. We would like to include additional species: advice from local experts is welcome and will speed the process. A few of the species listed fall into the category of pests; but most - whether resident or visitor - are desirable additions to the neighborhood. We hope you will enjoy using this booklet to identify the wildlife you see around you. Kay Loughman November 2005 2 Contents Birds Turkey Vulture Bewick’s Wren Red-tailed Hawk Wrentit American Kestrel Ruby-crowned Kinglet California Quail American Robin Mourning Dove Hermit thrush Rock Pigeon Northern Mockingbird Band-tailed -

On the Road Again ... Heading North

Newsletter of The Delaware Bay Lighthouse Keepers and Friends Association, Inc. Volume 37 Issue 16 “Our mission is to preserve the history of the Winter 2018 Delaware Bay and River Lighthouses, Lightships and their Keepers” ON THE ROAD AGAIN ... HEADING NORTH Having never been to the Eastern Maritime Provinces of Canada, we decided to sign up for a nine day bus tour of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. After traveling north and going through customs, we crossed the US/Canadian border at Calais, Maine. Moving our watches one hour ahead to Atlantic Daylight Saving Time, we proceeded to the Hilton Hotel in St. John, New Brunswick. Our hotel was located on the Bay of Fundy noted for its drastic tide changes. The tide ebbs or rises one foot every 15 minutes. Another feature of this Bay is the “reverse falls;” when the tide ebbs, the water flows UP the falls…strange indeed. Two of New Brunswick’s earliest recorded lighthouses are both located on the Bay of Fundy. One, Campobello Island Light (a), was constructed on the island where President Franklin Roosevelt spent his summers. This lighthouse is accessible on foot only at low tide. The other located on the Bay of Fundy is the eight meter tall Cape Enrage Light built in 1848. The majority of Canadian lighthouses are red and white so they can easily be seen during the heavy winter snowstorms. New Brunswick boasts of over 90 lighthouses. We crossed from St. John, NB to Digby, Nova Scotia by ferry and continued on to Wolfville, NS. -

The Care and Feeding of Trained Hawks and Falcons by Jim Roush

Volume 27 | Issue 2 Article 8 1965 The aC re And Feeding Of Trained Hawks And Falcons Jim Roush Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/iowastate_veterinarian Part of the Veterinary Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Roush, Jim (1965) "The aC re And Feeding Of Trained Hawks And Falcons," Iowa State University Veterinarian: Vol. 27 : Iss. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/iowastate_veterinarian/vol27/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Iowa State University Veterinarian by an authorized editor of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Care And Feeding Of Trained Hawks And Falcons by Jim Roush Falconry is the art of training hawks, is the first few months after hatching. falcons, and eagles to pursue and capture Baby hawks are extremely frail and tender wild game. It is perhaps the oldest field and they are very susceptible to trauma sport; in fact it was one of the ways of and the forces of nature. They are also procuring meat for the table before fire very susceptible to the nutritional dis arms were developed. During the first half orders such as rickets, perosis (slipped of this century this ancient sport has in Achille's tendon) etc. Louse powders com creased in popularity. This is probably due monly used on cattle and poultry can kill to the rising standard of living and a sub them. -

Natural History of the Gyrfalcon in the Central Canadian Arctic K.G

ARCTIC VOL. 41, NO. 1 (MARCH 1988) P. 31-38 Natural History of the Gyrfalcon in the Central Canadian Arctic K.G. POOLE' and R.G. BROMLEY2 (Received 24 March 1987; accepted in revised form 24 September 1987) ABSTRACT. A population of breeding gyrfalcons was studied from 1982to 1986 on 2000a km2 area in thecentral Arctic of the NorthwestTerritories. Each year 14-18 territories were occupied. The meanintemest distance was 10.6 km, giving oneof the highest recorded densitiesfor the species. There was a tendency for regularity in spacing of territories. Most (85%) nests were in abandoned stick nests of common ravens or golden eagles. Rough-legged hawk nests were not used by gyrfalcons, despite numerous available.date Mean of initiation of laying was 8 May. Meansize of clutch was 3.80 and of brood was 2.53, and mean productivity was 1SO fledged young. A reduction of 48% from estimated numberof eggs laid to number of fledglings was determined. Reproductive success declined with increased severity of spring weather, notablydays increased and amount of precipitation. Key words: gyrfalcon (Falco rusticolus),natural history, reproductive ecology, central Arctic RÉSUMÉ. Qtre 1982 et 1986, on a étudié une populationde gerfauts en reproduction dans une zone de 2000 km2dans la région centrale arctiquedes Territoires du Nord-Ouest. Quatorze des 18 aires étaient occupées chaque année. La distance entremoyenne les nids étaitde 10,6km, soit la plus grande densité relevée pour cetteespèce. Les aires avaient tendanceB être espacéesrégulitrement. La plupart des nids(85 p. cent) étaient situésdans des nids de brindilles occupés précédemment pardes corbeaux communsou des aigles dorés. -

Click Here for New Falconry Films Western Sporting: New Falconry Films to Our List!

CLICK HERE FOR NEW FALCONRY FILMS WESTERN SPORTING: NEW FALCONRY FILMS TO OUR LIST! FD1050 FD2045 FD2009 FD2005 HUNTING HAWKS IN ENGLAND Pastime Videos, 60 Minutes FD1048 The ancient art of falconry: hunting wild HOUSE OF GROUSE quarry with a trained hawk or falcon is SkyKing Productions, 39 Minutes FD1054 very exciting. We follow two North Steve's film-making abilities have EAGLE JOURNAL American Red-tailed Hawks and their improved greatly in the past few years! CorJo Productions, 30 minutes trainers, by day and by night, in their This is by far his greatest achievement In the USA, eagle falconry is gaining search for prey in the woods and open and it shows what is without a doubt popularity. More Golden Eagles are countryside of England. the most impressive longwing flights ever coming into the hands of falconers these There are a lot of authentic action captured on film. This new standard of days due to depredation permits. They sequences. The quarry these raptors falconry filming will set the standard on are fast, powerful raptors that can catch is primarily used as food to feed into the future. generally fly down anything in the field. not only them but numerous other All the elements of the high desert This video gives the viewer a rare hawks, owls and falcons, including many are included so we get a feel for the glimpse into the world of hunting with injured birds. They are all expertly cared wildlife, habitat, dramatic scenery as well Golden Eagles. Eagle falconer, Joe for at the Hagley Falconry & Bird as the falconry. -

Relationship of Anting and Sunbathing to Molting in Wild Birds

RELATIONSHIP OF ANTING AND SUNBATHING TO MOLTING IN WILD BIRDS ELOISE F. lPOTTER AND DORIS C. HAUSER • AviAr• anting has generateda large and somewhatcontroversial body of literature, much of it based upon the behavior of captive or experi- mental birds (e.g. Ivor 1943, Whitaker 1957, Weisbrod 1971), birds treat- ing plumagewith substancesother than ants (recently with mothballs in Dubois 1969 and with lemon oil in Johnson 1971), or single oc- currencesfrom widely scatteredgeographical locations. McAtee (1954) advisedthat in searchingfor a reasonabletheory as to why birds ant only recordsfrom wild birds using ants should be examined. The authors agree with McAtee and further believe that data should be considered comparableonly when taken from a limited geographicalregion (e.g. temperateNorth America in Potter 1970). The literatureon antinghas beenreviewed several times (Groskin 1950, Whitaker 1957, Chisholm1959, Simmons1966, Potter 1970). Principal theoriesare (1) that anting birds "derive sensualpleasure from anting, possiblysexual stimulation" (Whitaker 1957); (2) that ant secretions prevent, remove, or otherwise control ectoparasiteinfestation (Groskin 1950, Dubinin in Kelso and Nice 1963, Simmons1966); (3) that ant secretionsmay be helpful in feather maintenanceby increasingflow of salivafor preening,removing stale preen oil and other lipids,or increasing feather wear resistance(Simmons 1966); and (4) that ant secretions sootheskin irritated by the emergenceof new feathers (Southern 1963, Potter 1970). Only four authors have publisheda dozen or more anting recordsinvolving wild birds usingants and takingplace in or near a single location in temperate North America. These are Brackbill (1948) from Maryland, Groskin(1950) from Pennsylvania,Potter (1970) from North Carolina, and Hauser (1973) also from North Carolina. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Scientific Note

Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association, 2l(4):474-476,2OO5 Copyright @ 2005 by the American Mosquito Control Association, Inc. SCIENTIFIC NOTE DETECTION OF WEST NILE VIRUS RNA FROM THE LOUSE FLY ICO STA AMERICANA (DIPTERA: HIPPOBOSCIDAE) ARY FARAJOLLAHI,'.' WAYNE J. CRANS,I DIANE NICKERSON,3 PATRICIA BRYANT4 BRUCE WOLE4 AMY GLASER,5 INn THEODORE G. ANDREADIS6 ABSTRACT West Nile virus (WNV) was detected by Taqman reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction in 4 of 85 (4.7Vo) blood-engorged (n : 2) and unengorged (n : 2) Icosta americana (Leach) hippoboscid flies that were collected from wild raptors submitted to a wildlife rehabilitation center in Mercer County, NJ, in 2003. This report represents an additional detection of WNV in a nonculicine arthropod in North America and the first documented detection of the virus in unengorged hippoboscid flies, further suggesting a possible role that this species may play in the transmission of WNV in North America. KEY WORDS West Nile vrrns, Icosta americana, Hippoboscidae, raptors West Nile virus (WNV) is a flavivirus that rs blood feeders that are commonly associated with principally maintained in an enzootic cycle between birds of prey. Both sexes readily take blood (Be- Culex mosquitoes and avian amplifying hosts. To quaert 1952, 1953; Maa and Peterson 1987) and date, the virus has been detected in or isolated from females are viviparous, exhibiting a high frequency 59 species of mosquitoes in the United States and of blood feeding due to nutritional demands of de- Canada (CDC 2004) and the importance of mos- veloping larvae (Bequaert 1952). Host speciflcity quitoes as enzootic and epidemic vectors of WNV varies greatly among bird-feeding species (Lloyd in North America is well established (Andreadis et 2OO2),bult most species remain and feed on the host al. -

Parasites of the Neotropic Cormorant Nannopterum (Phalacrocorax) Brasilianus (Aves, Phalacrocoracidae) in Chile

Original Article ISSN 1984-2961 (Electronic) www.cbpv.org.br/rbpv Parasites of the Neotropic cormorant Nannopterum (Phalacrocorax) brasilianus (Aves, Phalacrocoracidae) in Chile Parasitos da biguá Nannopterum (Phalacrocorax) brasilianus (Aves, Phalacrocoracidae) do Chile Daniel González-Acuña1* ; Sebastián Llanos-Soto1,2; Pablo Oyarzún-Ruiz1 ; John Mike Kinsella3; Carlos Barrientos4; Richard Thomas1; Armando Cicchino5; Lucila Moreno6 1 Laboratorio de Parásitos y Enfermedades de Fauna Silvestre, Departamento de Ciencia Animal, Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria, Universidad de Concepción, Chillán, Chile 2 Laboratorio de Vida Silvestre, Departamento de Ciencia Animal, Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria, Universidad de Concepción, Chillán, Chile 3 Helm West Lab, Missoula, MT, USA 4 Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria, Universidad Santo Tomás, Concepción, Chile 5 Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Mar del Plata, Argentina 6 Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Oceanográficas, Universidad de Concepción, Concepción, Chile How to cite: González-Acuña D, Llanos-Soto S, Oyarzún-Ruiz P, Kinsella JM, Barrientos C, Thomas R, et al. Parasites of the Neotropic cormorant Nannopterum (Phalacrocorax) brasilianus (Aves, Phalacrocoracidae) in Chile. Braz J Vet Parasitol 2020; 29(3): e003920. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612020049 Abstract The Neotropic cormorant Nannopterum (Phalacrocorax) brasilianus (Suliformes: Phalacrocoracidae) is widely distributed in Central and South America. In Chile, information about parasites for this species is limited to helminths and nematodes, and little is known about other parasite groups. This study documents the parasitic fauna present in 80 Neotropic cormorants’ carcasses collected from 2001 to 2008 in Antofagasta, Biobío, and Ñuble regions. Birds were externally inspected for ectoparasites and necropsies were performed to examine digestive and respiratory organs in search of endoparasites.