Introduction of an Element of Competition in Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free to Choose Video Tape Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1n39r38j No online items Inventory to the Free to Choose video tape collection Finding aid prepared by Natasha Porfirenko Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2008 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory to the Free to Choose 80201 1 video tape collection Title: Free to Choose video tape collection Date (inclusive): 1977-1987 Collection Number: 80201 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 10 manuscript boxes, 10 motion picture film reels, 42 videoreels(26.6 Linear Feet) Abstract: Motion picture film, video tapes, and film strips of the television series Free to Choose, featuring Milton Friedman and relating to laissez-faire economics, produced in 1980 by Penn Communications and television station WQLN in Erie, Pennsylvania. Includes commercial and master film copies, unedited film, and correspondence, memoranda, and legal agreements dated from 1977 to 1987 relating to production of the series. Digitized copies of many of the sound and video recordings in this collection, as well as some of Friedman's writings, are available at http://miltonfriedman.hoover.org . Creator: Friedman, Milton, 1912-2006 Creator: Penn Communications Creator: WQLN (Television station : Erie, Pa.) Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1980, with increments received in 1988 and 1989. -

Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (P

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (p. 1) District Conditions (p.18) Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review vol. 5, no 3 This publication primarily presents economic research aimed at improving policymaking by the Federal Reserve System and other governmental authorities. Produced in the Research Department. Edited by Arthur J. Rolnick, Richard M. Todd, Kathleen S. Rolfe, and Alan Struthers, Jr. Graphic design and charts drawn by Phil Swenson, Graphic Services Department. Address requests for additional copies to the Research Department. Federal Reserve Bank, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55480. Articles may be reprinted if the source is credited and the Research Department is provided with copies of reprints. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review/Fall 1981 Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas J. Sargent Neil Wallace Advisers Research Department Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and Professors of Economics University of Minnesota In his presidential address to the American Economic in at least two ways. (For simplicity, we will refer to Association (AEA), Milton Friedman (1968) warned publicly held interest-bearing government debt as govern- not to expect too much from monetary policy. In ment bonds.) One way the public's demand for bonds particular, Friedman argued that monetary policy could constrains the government is by setting an upper limit on not permanently influence the levels of real output, the real stock of government bonds relative to the size of unemployment, or real rates of return on securities. -

Forms of Government

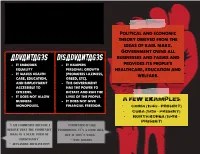

communism An economic ideology Political and economic theory derived from the ideas of karl marx. Government owns all Advantages DISAdvantages businesses and farms and - It embodies - It hampers provides its people's equality personal growth healthcare, education and - It makes health (promotes laziness, welfare. care, education, greed, etc). and employment - The government accessible to has the power to citizens. dictate and run the - It does not allow lives of the people. business - It does not give A Few Examples: monopolies. financial freedom. - China (1949 – Present) - Cuba (1959 – Present) - North Korea (1948 – Present) “I am communist because I “Communism is like believe that the comMunist prohibition. It’s a good idea, ideal is a state form of but it won’t work.” christianity” - will Rogers - Alexander Zhuravlyovv Socialism Government owns many of An Economic Ideology the larger industries and provide education, health and welfare services while Advantages DISAdvantages allowing citizens some - There is a balance - Bureaucracy hampers economic choices between wealth and the delivery of earnings services. - There is equal access - People are to health care and unmotivated to A Few Examples: education develop Vietnam - It breaks down social entrepreneurial skills. Laos barriers - The government has Denmark too much control Finland “The meaning of peace is “Socialism is workable only the absence of opposition to in heaven where it isn’t need socialism” and in where they’ve got it.” - Karl Marx - Cecil Palmer Capitalism Free-market -

Education Policy and Friedmanomics: Free Market Ideology and Its Impact

Education Policy and Friedmanomics: Free Market Ideology and Its Impact on School Reform Thomas J. Fiala Department of Teacher Education Arkansas State University Deborah Duncan Owens Department of Teacher Education Arkansas State University April 23, 2010 Paper presented at the 68th Annual National Conference of the Midwest Political Science Association Chicago, Illinois 2 ABSTRACT The purpose of this paper is to examine the impact of neoliberal ideology, and in particular, the economic and social theories of Milton Friedman on education policy. The paper takes a critical theoretical approach in that ultimately the paper is an ideological critique of conservative thought and action that impacts twenty-first century education reform. Using primary and secondary documents, the paper takes an historical approach to begin understanding how Friedman’s free market ideas helped bring together disparate conservative groups, and how these groups became united in influencing contemporary education reform. The paper thus considers the extent to which free market theory becomes the essence of contemporary education policy. The result of this critical and historical anaysis gives needed additional insights into the complex ideological underpinnings of education policy in America. The conclusion of this paper brings into question the efficacy and appropriateness of free market theory to guide education policy and the use of vouchers and choice, and by extension testing and merit-based pay, as free market panaceas to solving the challenges schools face in the United States. Administrators, teachers, education policy makers, and those citizens concerned about education in the U.S. need to be cautious in adhering to the idea that the unfettered free market can or should drive education reform in the United States. -

Liberty, Property and Rationality

Liberty, Property and Rationality Concept of Freedom in Murray Rothbard’s Anarcho-capitalism Master’s Thesis Hannu Hästbacka 13.11.2018 University of Helsinki Faculty of Arts General History Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Filosofian, historian, kulttuurin ja taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos Tekijä – Författare – Author Hannu Hästbacka Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Liberty, Property and Rationality. Concept of Freedom in Murray Rothbard’s Anarcho-capitalism Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Yleinen historia Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu -tutkielma year 100 13.11.2018 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Murray Rothbard (1926–1995) on yksi keskeisimmistä modernin libertarismin taustalla olevista ajattelijoista. Rothbard pitää yksilöllistä vapautta keskeisimpänä periaatteenaan, ja yhdistää filosofiassaan klassisen liberalismin perinnettä itävaltalaiseen taloustieteeseen, teleologiseen luonnonoikeusajatteluun sekä individualistiseen anarkismiin. Hänen tavoitteenaan on kehittää puhtaaseen järkeen pohjautuva oikeusoppi, jonka pohjalta voidaan perustaa vapaiden markkinoiden ihanneyhteiskunta. Valtiota ei täten Rothbardin ihanneyhteiskunnassa ole, vaan vastuu yksilöllisten luonnonoikeuksien toteutumisesta on kokonaan yksilöllä itsellään. Tutkin työssäni vapauden käsitettä Rothbardin anarko-kapitalistisessa filosofiassa. Selvitän ja analysoin Rothbardin ajattelun keskeisimpiä elementtejä niiden filosofisissa, -

Nine Lives of Neoliberalism

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) Book — Published Version Nine Lives of Neoliberalism Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) (2020) : Nine Lives of Neoliberalism, ISBN 978-1-78873-255-0, Verso, London, New York, NY, https://www.versobooks.com/books/3075-nine-lives-of-neoliberalism This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/215796 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative -

Free to Choose

June 9, 2005 COMMENTARY Free to Choose By MILTON FRIEDMAN June 9, 2005; Page A16 Little did I know when I published an article in 1955 on "The Role of Government in Education" that it would lead to my becoming an activist for a major reform in the organization of schooling, and indeed that my wife and I would be led to establish a foundation to promote parental choice. The original article was not a reaction to a perceived deficiency in schooling. The quality of schooling in the United States then was far better than it is now, and both my wife and I were satisfied with the public schools we had attended. My interest was in the philosophy of a free society. Education was the area that I happened to write on early. I then went on to consider other areas as well. The end result was "Capitalism and Freedom," published seven years later with the education article as one chapter. With respect to education, I pointed out that government was playing three major roles: (1) legislating compulsory schooling, (2) financing schooling, (3) administering schools. I concluded that there was some justification for compulsory schooling and the financing of schooling, but "the actual administration of educational institutions by the government, the 'nationalization,' as it were, of the bulk of the 'education industry' is much more difficult to justify on [free market] or, so far as I can see, on any other grounds." Yet finance and administration "could readily be separated. Governments could require a minimum of schooling financed by giving the parents vouchers redeemable for a given sum per child per year to be spent on purely educational services. -

Friedman's Monetary Framework

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Friedman’s Monetary Framework: Some Lessons Ben S. Bernanke t is an honor and a pleasure to have this opportunity, on the anniversary of Milton and Rose Friedman’s popular classic, Free to Choose, to speak on I Milton Friedman’s monetary framework and his contributions to the theory and practice of monetary policy. About a year ago, I also had the honor, at a conference at the University of Chicago in honor of Milton’s ninetieth birthday, to discuss the contribution of Friedman’s classic 1963 work with Anna Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States.1 I mention this earlier talk not only to indicate that I am ready and willing to praise Friedman’s contributions wherever and whenever anyone will give me a venue but also because of the critical influ- ence of A Monetary History on both Friedman’s own thought and on the views of a generation of monetary policymakers. In their Monetary History, Friedman and Schwartz reviewed nearly a cen- tury of American monetary experience in painstaking detail, providing an his- torical analysis that demonstrated the importance of monetary forces in the economy far more convincingly than any purely theoretical or even economet- ric analysis could ever do. Friedman’s close attention to the lessons of history for economic policy is an aspect of his approach to economics that I greatly admire. Milton has never been a big fan of government licensing of profession- als, but maybe he would make an exception in the case of monetary policy- makers. -

The Increasingly Libertarian Milton Friedman: an Ideological Profile

Discuss this article at Journaltalk: http://journaltalk.net/articles/5820 ECON JOURNAL WATCH 11(1) January 2014: 81-96 The Increasingly Libertarian Milton Friedman: An Ideological Profile Lanny Ebenstein1 LINK TO ABSTRACT That Milton Friedman (1912–2006) grew more consistently, even stridently, libertarian over the course of the last 50 years of his long life has been noticed by several writers. Among these is Brian Doherty (2012), who published a book review whose title I also use for the present article, simply because it says it best.2 The present article is written as something of a follow-up to Dan Hammond’s recent ideological profile of Friedman (Hammond 2013), which I find highly admirable as far as it goes, but which leaves off how Friedman continued to grow more libertarian during the last several decades of his life. The “first Chicago school” and Milton Friedman to the late 1940s Although there are no hard-and-fast definitions, classical liberalism favors free trade among nations and a presumption of liberty in domestic issues. It advo- cates limited and efficient government, and low taxes. It was and has generally remained anti-imperialist, anti-interventionist, and socially tolerant. Such was the larger view of Jacob Viner, Frank Knight, Henry Simons, and other economists at the University of Chicago from the middle 1920s to middle 1940s. It was apparent 1. University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106. 2. Doherty (2013) also speaks of Friedman’s “later, more libertarian years.” VOLUME 11, NUMBER 1, JANUARY 2014 81 EBENSTEIN in this period that the federal government increasingly involved itself in the economy, and during the Great Depression the Chicago economists were almost unanimous in calling for stimulative monetary and fiscal policies and relief pro- grams (Davis 1971). -

Pragmatism As a Pillar of the New Developmentalism Pragmatismo Como Um Pilar Do Novo Desenvolvimentismo

Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, vol 40, nº 2, pp 376-397, April-June/2020 Pragmatism as a pillar of the New Developmentalism Pragmatismo como um pilar do Novo Desenvolvimentismo JOÃO PAIVA-SILVA*,** RESUMO: Os estudiosos do Novo Desenvolvimentismo geraram um corpo substancial de conhecimento sobre a transformação estrutural e as políticas que devem ser adotadas para promover sua conquista. No entanto, como é discutido neste artigo, o Novo Desenvolvi- mentismo, em contraste com o Neoliberalismo, carece de uma base filosófica sólida para legitimar as políticas que favorecem por outros motivos que não a capacidade de gerar prosperidade. Também se argumenta que os novos-desenvolvimentistas deveriam adotar explicitamente uma filosofia pragmática para se tornar uma alternativa mais séria a outras doutrinas da economia política. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Filosofia econômica; história do pensamento econômico; desenvolvi- mento econômico; Novo Desenvolvimentismo; institucionalismo. ABSTRACT: The scholars of New Developmentalism have generated a substantial body of knowledge regarding structural transformation and the policies that should be adopted to foster its achievement. Nevertheless, as is argued in this paper, New Developmentalism, by contrast with Neoliberalism, lacks a strong philosophical foundation to legitimise the poli- cies it favours on grounds other than their ability to generate prosperity. It is also argued that new-developmentalists should explicitly adopt a pragmatic philosophy in order to be- come a more serious alternative to other political economy doctrines. KEYWORDS: Economic philosophy; history of economic thought; economic development; New Developmentalism; institutionalism. JEL Classification: A13; B5; O10. * Centre for African and Development Studies – Lisbon School of Economics and Management – Uni- versity of Lisbon, Lisboa/Portugal. -

Is Neoliberalism Consistent with Individual Liberty? Friedman, Hayek and Rand on Education Employment and Equality

International Journal of Teaching and Education Vol. IV, No. 4 / 2016 DOI: 10.20472/TE.2016.4.4.003 IS NEOLIBERALISM CONSISTENT WITH INDIVIDUAL LIBERTY? FRIEDMAN, HAYEK AND RAND ON EDUCATION EMPLOYMENT AND EQUALITY IRIT KEYNAN Abstract: In their writings, Milton Friedman, Friedrich August von Hayek and Ayn Rand have been instrumental in shaping and influencing neoliberalism through their academic and literary abilities. Their opinions on education, employment and inequality have stirred up considerable controversy and have been the focus of many debates. This paper adds to the debate by suggesting that there is an internal inconsistency in the views of neoliberalism as reflected by Friedman, Hayek and Rand. The paper contends that whereas their neoliberal theories promote liberty, the manner in which they conceptualize this term promotes policies that would actually deny the individual freedom of the majority while securing liberty and financial success for the privileged few. The paper focuses on the consequences of neoliberalism on education, and also discusses how it affects employment, inequality and democracy. Keywords: Neoliberalism; liberty; free market; equality; democracy; social justice; education; equal opportunities; Conservativism JEL Classification: B20, B31, P16 Authors: IRIT KEYNAN, College for Academic Studies, Israel, Email: [email protected] Citation: IRIT KEYNAN (2016). Is neoliberalism consistent with individual liberty? Friedman, Hayek and Rand on education employment and equality. International Journal of Teaching and Education, Vol. IV(4), pp. 30-47., 10.20472/TE.2016.4.4.003 Copyright © 2016, IRIT KEYNAN, [email protected] 30 International Journal of Teaching and Education Vol. IV, No. 4 / 2016 I. Introduction Neoliberalism gradually emerged as a significant ideology during the twentieth century, in response to the liberal crisis of the 1930s. -

CAPITALISM and FREEDOM Milton Friedman October 1St, 1962

CAPITALISM AND FREEDOM Milton Friedman October 1st, 1962 OVERVIEW: In Capitalism And Freedom, former University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman argues for economic freedom as a precondition for political freedom. He defines “liberal” in European Enlightenment terms, contrasting the title with American usage that he contends has been corrupted. - - - - - - - - - ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL FREEDOM: At the outset of the book, Friedman outlines his primary thesis that there is an “inescapable connection between capitalism and democracy.” In this meaning, not only do the two customs of decentralized public control have an elective affinity as forms of democratic empowerment, but also as a counter to unconstrained governmental power, which displaces the free market, weakens democracy, and eventually leads to a dictatorship. Thus, capitalism is a prerequisite for freedom. He criticizes the notion that politics and economics can be regarded separately and that any combination of political and economic system is possible. He calls this view “a delusion,” holding that there is “an intimate connection between economics and politics.” Though Friedman concedes the possibility of an economically free and politically repressed society, the opposite is completely impossible. Furthermore, that economic freedom is a crucial element of individual freedom in its own right, but is also critical for supporting political freedom. As he writes, “Political freedom means the absence of coercion of a man by his fellow men. The fundamental threat to NOTABLE QUOTE freedom is power to coerce, be it in the hands of a monarch, a dictator, an oligarchy, or a “A society that puts equality momentary majority… By removing the organization of economic activity from the control of before freedom will get neither.