Is Neoliberalism Consistent with Individual Liberty? Friedman, Hayek and Rand on Education Employment and Equality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michael Polanyi and Early Neoliberalism

MICHAEL POLANYI AND EARLY NEOLIBERALISM Martin Beddeleem Keywords: Friedrich Hayek, Louis Rougier, Michael Polanyi, Mont-Pèlerin Society, neoliberalism, planning, Walter Lippmann ABSTRACT1 Between the late 1930s and the 1950s, Michael Polanyi came in close contact with a diverse cast of intellectuals seeking a renewal of the liberal doctrine. The elaboration of this “neoliberalism” happened through a transnational collaboration between economists, philosophers, and social theorists, united in their rejection of central planning. Defining a common agenda for this “early neoliberalism” offered an opportunity to discard the old laissez-faire doctrine and restore a supervisory role of the state. Ultimately, post-war dissensions regarding the direction of these efforts led Polanyi away from the neoliberal core. Between the publication of his pamphlet on the failures of economic planning in the Soviet Union in 1936 (CF, 61-95) and that of The Logic of Liberty in 1951, Michael Polanyi progressively lost interest in chemistry and started to investigate the political and sociological conditions necessary to scientific freedom and the pursuit of truth. During that time, he became involved with a group of scholars who, equally, perceived the democratic collapse of Europe as a wake-up call for a restatement of its liberal tradition. Whereas the values of individual dignity and social progress that liber- alism carried were needed then more than ever, they agreed that the method to achieve these ideals had become obsolete. Therefore, they focused their efforts on revamping a science of liberalism, which could answer the scientific claims of plannism and totalitar- ian ideologies. Tradition & Discovery: The Journal of the Polanyi Society 45:3 © 2019 by the Polanyi Society 31 For two decades, Michael Polanyi took part in the inception and the consolida- tion of “early neoliberalism” (Schulz-Forberg 2018; Beddeleem 2019), a period that predates the later development of neoliberalism from the 1960s onwards. -

Analysis Note: the Economic Case for Gender Equality

Analysis Note: the Economic Case for Gender Equality Mark SMITH and Francesca BETTIO August 2008 This analysis note was financed by and prepared for the use of the European Commission, Directorate- General for Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion or position of the European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities. Neither the Commission nor any person acting on its behalf is responsible for the use that might be made of the information contained in this publication. EGGE – European Commission's Network of Experts on Employment and Gender Equality issues – Fondazione Giacomo Brodolini EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Although gender equality is widely regarded as a worthwhile goal it is also seen as having potential costs or even acting as a constraint on economic growth and while this view may not be evident in official policy it remains implicit in policy decisions. For example, where there is pressure to increase the quantity of work or promote growth, progress towards gender equality may be regarded as something that can be postponed. However, it is possible to make an Economic Case for gender equality, as an investment, such that it can be regarded as a means to promote growth and employment rather than act as a cost or constraint. As such equality policies need to be seen in a wider perspective with a potentially greater impact on individuals, firms, regions and nations. The Economic Case for gender equality can be regarded as going a step further than the so- called Business Case. While the Business Case emphasises the need for equal treatment to reflect the diversity among potential employees and an organisation’s customers the Economic Case stresses economic benefits at a macro level. -

25 Mill on Justice and Rights DAVID O

25 Mill on Justice and Rights DAVID O. BRINK Mill develops his account of the juridical concepts of justice and rights in several d ifferent contexts and works. He discusses both the logic of these juridical concepts – what rights and justice are and how they are related to each other and to utility – and their substance – what rights we have and what justice demands. Though the logic and substance of these juridical concepts are distinct, they are related. An account of the logic of rights and justice should constrain how one justifies claims about their substance, and ways of defending what rights we have and what justice demands pre- suppose claims about the logic of these concepts. We would do well to examine Mill’s central claims about the substance of justice and rights before turning to his views about their logic. Mill links demands of justice and individual rights. He defends rights to basic liberties in On Liberty (1859), women’s rights to sexual equality as a matter of justice in The Subjection of Women (1869), and rights to fair equality opportunity in Principles of Political Economy (1848) and The Subjection of Women. While these are Mill’s central claims about the substance of rights and justice, he is attracted to three different conceptions of the logic of rights and justice. His most explicit discussion occurs in Chapter V of Utilitarianism (1861) in response to the worry that justice is a moral con- cept independent of considerations of utility. There, Mill develops claims about justice and rights that treat them as related parts of an indirect utilitarian conception of duty that explains fundamental moral notions in terms of expedient sanctioning responses. -

How Economic Inequality Shapes Mobility Expectations and Behavior

How Economic Inequality Shapes Mobility Expectations and Behavior in Disadvantaged Youth Alexander S. Browmana Mesmin Destinb,c,d Melissa S. Kearneye,g Phillip B. Levinef,g a Lynch School of Education, Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA 02467 b School of Education and Social Policy, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208 c Department of Psychology, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208 d Institute for Policy Research, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208 e Department of Economics, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 f Department of Economics, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA 02481 g National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA 02138 Nature Human Behaviour, 2019 © Springer Nature Limited, 2019. This paper is not the copy of record and may not exactly replicate the authoritative document published in Nature Human Behaviour. The final article is available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0523-0 2 Abstract Economic inequality can have a range of negative consequences for those in younger generations, particularly for those from lower-socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds. Economists and psychologists, among other social scientists, have addressed this issue, but have proceeded largely in parallel. This Perspective outlines how these disciplines have proposed and provided empirical support for complementary theoretical models. Specifically, both disciplines emphasize that inequality weakens people’s belief in socioeconomic opportunity, thereby reducing the likelihood that low-SES young people will engage in behaviors that would improve their chances of upward mobility (e.g., persisting in school, averting teenage pregnancy). In integrating the methods and techniques of economics and psychology, we offer a cohesive framework for considering this issue. -

Hayek's the Constitution of Liberty

Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty An Account of Its Argument EUGENE F. MILLER The Institute of Economic Affairs contenTs The author 11 First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Foreword by Steven D. Ealy 12 The Institute of Economic Affairs 2 Lord North Street Summary 17 Westminster Editorial note 22 London sw1p 3lb Author’s preface 23 in association with Profile Books Ltd The mission of the Institute of Economic Affairs is to improve public 1 Hayek’s Introduction 29 understanding of the fundamental institutions of a free society, by analysing Civilisation 31 and expounding the role of markets in solving economic and social problems. Political philosophy 32 Copyright © The Institute of Economic Affairs 2010 The ideal 34 The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a PART I: THE VALUE OF FREEDOM 37 retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. 2 Individual freedom, coercion and progress A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. (Chapters 1–5 and 9) 39 isbn 978 0 255 36637 3 Individual freedom and responsibility 39 The individual and society 42 Many IEA publications are translated into languages other than English or are reprinted. Permission to translate or to reprint should be sought from the Limiting state coercion 44 Director General at the address above. -

Free to Choose Video Tape Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1n39r38j No online items Inventory to the Free to Choose video tape collection Finding aid prepared by Natasha Porfirenko Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2008 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory to the Free to Choose 80201 1 video tape collection Title: Free to Choose video tape collection Date (inclusive): 1977-1987 Collection Number: 80201 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 10 manuscript boxes, 10 motion picture film reels, 42 videoreels(26.6 Linear Feet) Abstract: Motion picture film, video tapes, and film strips of the television series Free to Choose, featuring Milton Friedman and relating to laissez-faire economics, produced in 1980 by Penn Communications and television station WQLN in Erie, Pennsylvania. Includes commercial and master film copies, unedited film, and correspondence, memoranda, and legal agreements dated from 1977 to 1987 relating to production of the series. Digitized copies of many of the sound and video recordings in this collection, as well as some of Friedman's writings, are available at http://miltonfriedman.hoover.org . Creator: Friedman, Milton, 1912-2006 Creator: Penn Communications Creator: WQLN (Television station : Erie, Pa.) Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1980, with increments received in 1988 and 1989. -

Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (P

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (p. 1) District Conditions (p.18) Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review vol. 5, no 3 This publication primarily presents economic research aimed at improving policymaking by the Federal Reserve System and other governmental authorities. Produced in the Research Department. Edited by Arthur J. Rolnick, Richard M. Todd, Kathleen S. Rolfe, and Alan Struthers, Jr. Graphic design and charts drawn by Phil Swenson, Graphic Services Department. Address requests for additional copies to the Research Department. Federal Reserve Bank, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55480. Articles may be reprinted if the source is credited and the Research Department is provided with copies of reprints. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review/Fall 1981 Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas J. Sargent Neil Wallace Advisers Research Department Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and Professors of Economics University of Minnesota In his presidential address to the American Economic in at least two ways. (For simplicity, we will refer to Association (AEA), Milton Friedman (1968) warned publicly held interest-bearing government debt as govern- not to expect too much from monetary policy. In ment bonds.) One way the public's demand for bonds particular, Friedman argued that monetary policy could constrains the government is by setting an upper limit on not permanently influence the levels of real output, the real stock of government bonds relative to the size of unemployment, or real rates of return on securities. -

Forms of Government

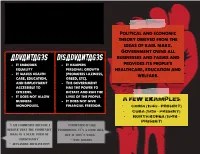

communism An economic ideology Political and economic theory derived from the ideas of karl marx. Government owns all Advantages DISAdvantages businesses and farms and - It embodies - It hampers provides its people's equality personal growth healthcare, education and - It makes health (promotes laziness, welfare. care, education, greed, etc). and employment - The government accessible to has the power to citizens. dictate and run the - It does not allow lives of the people. business - It does not give A Few Examples: monopolies. financial freedom. - China (1949 – Present) - Cuba (1959 – Present) - North Korea (1948 – Present) “I am communist because I “Communism is like believe that the comMunist prohibition. It’s a good idea, ideal is a state form of but it won’t work.” christianity” - will Rogers - Alexander Zhuravlyovv Socialism Government owns many of An Economic Ideology the larger industries and provide education, health and welfare services while Advantages DISAdvantages allowing citizens some - There is a balance - Bureaucracy hampers economic choices between wealth and the delivery of earnings services. - There is equal access - People are to health care and unmotivated to A Few Examples: education develop Vietnam - It breaks down social entrepreneurial skills. Laos barriers - The government has Denmark too much control Finland “The meaning of peace is “Socialism is workable only the absence of opposition to in heaven where it isn’t need socialism” and in where they’ve got it.” - Karl Marx - Cecil Palmer Capitalism Free-market -

Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse Nov 2003 RWP03-044 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. All works posted here are owned and copyrighted by the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism1 Mathias Risse John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University October 25, 2003 1. Left-libertarianism is not a new star on the sky of political philosophy, but it was through the recent publication of Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner’s anthologies that it became clearly visible as a contemporary movement with distinct historical roots. “Left- libertarian theories of justice,” says Vallentyne, “hold that agents are full self-owners and that natural resources are owned in some egalitarian manner. Unlike most versions of egalitarianism, left-libertarianism endorses full self-ownership, and thus places specific limits on what others may do to one’s person without one’s permission. Unlike right- libertarianism, it holds that natural resources may be privately appropriated only with the permission of, or with a significant payment to, the members of society. Like right- libertarianism, left-libertarianism holds that the basic rights of individuals are ownership rights. Left-libertarianism is promising because it coherently underwrites both some demands of material equality and some limits on the permissible means of promoting this equality” (Vallentyne and Steiner (2000a), p 1; emphasis added). -

Inheritance, Gifts, and Equal Opportunity

1 Inheritance, Gifts, and Equal Opportunity Dick Arneson For Duke University conference 12001 “It has become a commonplace to say we’re living in a second Gilded Age,” writes Paul Krugman, attributing the shift in common opinion to the recent work of the economist Thomas Piketty. More strikingly, according to Krugman, this recent scholarship suggests that we are “on a path back to ‘patrimonial capitalism,’ in which the commanding heights of the economy are controlled not by talented individuals but by family dynasties.”1 In the light of such worries, we might wonder about how inheritance and large gifts to individuals would be assessed in the lens of egalitarian political philosophies. This essay explores a part of this large topic. I look at the utilitarianism of John Stuart Mill along with Rawlsian fair equality of opportunity, luck egalitarian doctrines, and the burgeoning relational egalitarianism tradition. In the course of this survey, I tack back and forth between considering what the doctrine under review implies with respect to inheritance and gift-giving and considering whether the doctrine under review is sufficiently plausible so that we should care about its implications for this topic or any other. 1. Limits on Individual gains from gift and bequest. A permissive state policy on gifts and inheritance would allow that anyone who legitimately possesses property is free to pass along any portion of it to anyone she chooses, provided the would-be recipient accepts the bequest, and provided the intent of the giver is not to induce the recipient to violate a genuine duty, as occurs in bribery. -

Quong-Left-Libertarianism.Pdf

The Journal of Political Philosophy: Volume 19, Number 1, 2011, pp. 64–89 Symposium: Ownership and Self-ownership Left-Libertarianism: Rawlsian Not Luck Egalitarian Jonathan Quong Politics, University of Manchester HAT should a theory of justice look like? Any successful answer to this Wquestion must find a way of incorporating and reconciling two moral ideas. The first is a particular conception of individual freedom: because we are agents with plans and projects, we should be accorded a sphere of liberty to protect us from being used as mere means for others’ ends. The second moral idea is that of equality: we are moral equals and as such justice requires either that we receive equal shares of something—of whatever it is that should be used as the metric of distributive justice—or else requires that unequal distributions can be justified in a manner that is consistent with the moral equality of persons. These twin ideas—liberty and equality—are things which no sound conception of justice can properly ignore. Thus, like most political philosophers, I take it as given that the correct conception of justice will be some form of liberal egalitarianism. A deep and difficult challenge for all liberal egalitarians is to determine how the twin values of freedom and equality can be reconciled within a single theory of distributive justice. Of the many attempts to achieve this reconciliation, left-libertarianism is one of the most attractive and compelling. By combining the libertarian commitment to full (or nearly full) self-ownership with an egalitarian principle for the ownership of natural resources, left- libertarians offer an account of justice that appears firmly committed both to individual liberty, and to an egalitarian view of how opportunities or advantages must be distributed. -

Fantasies of Liberalism and Liberal Jurisprudence: State Law, Politics, and the Israeli-Arab-Palestinian Community Dr. Gad

1 Fantasies of Liberalism and Liberal Jurisprudence: State Law, Politics, and the Israeli-Arab-Palestinian Community Dr. Gad Barzilai Dr. Gad Barzilai is senior lecturer in political science and a jurist, co-director of the law, politics, and society program at Tel Aviv University. This paper was presented in different versions in the Center for the Study of Law and Society, Berkeley University, Center for Middle Eastern Studies, St. Antony’s College, Oxford University, faculty seminars at Tel Aviv University and the conference on Bergman, Hebrew University, Jerusalem. I would like to acknowledge helpful remarks made by Laura Edelman, Malcolm Feeley, Tamar Herman, Menachem Hofnung, Robert Kagan, David Kretzmer, Pnina Lahav, Noga Morag-Levin, Emanuel Ottollengi, Avi Shlaim, Ronen Shamir, Oren Yiftachel, and Efraim Yuchtman-Yaar. Yoav Dotan and Ruth Gavison were encouraging editors and two anonymous reviewers improved the article. Thanks. © Israel Law Review. 1 2 I. Between Bergman (1969) and Kaadan (2000) About thirty years after Bergman case1, Israel constitutional structure and its legal culture are not responsive to minority needs, and more largely to social needs of deprived communities. The liberal language and judicial review over Knesset legislation that have been empowered by and followed Bergman have not reconciled this utterly problematic discrepancy between jurisprudence and social needs. Bergman ruling has symbolized the outset of a new area in Israel jurisprudence, the area of liberalism, since it has empowered the notion of judicial counter majoritarianism as the center, however problematic, of democracy. It has been a modest ruling, and a careful one, dwelling only on procedural deficiencies as a cause of judicial abolition of parliamentary legislation.