134 Part One: Between the Wars When the Prime Minister Concluded

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MANUFACTURE of AEROPLANES 1N CANADA WILL BE Spurredj

MANUFACTURE OF AEROPLANES 1N CANADA WILL BE SPURREDj 1939 Sharp Expansion Ex-: pected Through Roose- by ~, velt .Proclamatiari ed States France, Great Britain" ,The: contracts specified that in -the and Australia. 0 event of war the planes could be ovw "The embargo proclamation, how- delivered to the British and other INVOLVE- LOCAL FIRM ever; -does, not interfere with the bgovernments in the United States. ' manufacture of similar , planes in A representative of one of the 4 ~; :N6W.YOrk, plane plants said to-day that work -Septa-7. - (CP) 1 Canada under licenses already ob- on the orders was continuing . The' --A sharp ~Xpansiou in Cana-. ; "tained by. the Dominion's manufac- finished aircraft, he said, probably ,than aeroplane manufacture' turers 'ftom American firms," " "the would be stored in New York or ex eted` as , a result of Presi-. dispatch says.,, ` some other; port in the hope the ft. Roosevelt's proclamation.,;, " . - According to information avail- United States embargo will bP ; able in Washington, four Canadian revoked at an early date and de- of, the'.United States Neutral- aircraft ;manufacturers have ar- livery proceed . Eit;, tlLe" New York Herald." rangements. with United States Three plants on the United Tribune " says - to-dAy'in",a-,,dis'-'~ firms . to produce planes of Ameri- States west coast were known to patt li from its" WasWngtOn can design, in the Dominion, Some bP manufacturing the planes for uf.oa ! of the other six :manufacturers in foreign delivery. They are the _ ` . .C1 t -Order in Half Canada may have such arrange- Douglas, Lockheed and . North meets, the, paper suggests. -

Number 5 Bombing and Gunnery School Dafoe, Saskatchewan

Number 5 Bombing and Gunnery School Dafoe, Saskatchewan By Stephen Carthy Introduction and Acknowledgements Born as children of the Roaring Twenties and growing up as adolescents of the Dirty Thirties, they were men mostly in their late teens or early twenties when World War II broke out. They enlisted in the air forces of the British Commonwealth. Their reasons were as individual as they were, for some it was a way to escape the joblessness of the Thirties, for others it was patriotism and a chance for adventure, for some it was peer pressure, or it may have been a combination of any of those. After completing their basic training in their homeland they were sent to Canada to train in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Of course, the vast majority of these young men went on to serve in various theatres of war after completing their training in Canada. Sadly, too many of them never returned to their homes. The British Commonwealth Air Training Program had an extremely good safety record and 131,553 aircrew were trained. Most of the accidents that occurred were minor, but some were serious, and some fatal. 856 trainee airmen were either seriously injured or killed. At #5 Bombing and Gunnery School near Dafoe, Saskatchewan one hundred and twenty-three accidents were recorded, most were minor. Because those who were killed were not casualties of theatres of war their sacrifice is sometimes forgotten. Nevertheless, they gave their lives in the service of their countries. Like those who gave their lives overseas, those who died in training accidents in Canada left their families and homes voluntarily to serve their countries. -

The Story of Sid Bregman 80 Glorious Years

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2019 CANADIAN WARPLANE HERITAGE MUSEUM 80 GLORIOUS YEARS Canadian Warplane Heritage’s DC-3 THE STORY OF SID BREGMAN And Spitfire MJ627 President & Chief Executive Officer David G. Rohrer Vice President – External Client Services Manager Controller Operations Cathy Dowd Brenda Shelley Sandra Price Curator Education Services Vice President – Finance Erin Napier Manager Ernie Doyle Howard McLean Flight Coordinator Chief Engineer Laura Hassard-Moran Donor Services Jim Van Dyk Manager Retail Manager Sally Melnyk Marketing Manager Shawn Perras Al Mickeloff Building Maintenance Volunteer Services Manager Food & Beverage Manager Administrator Jason Pascoe Anas Hasan Toni McFarlane Board of Directors Christopher Freeman, Chair David Ippolito Robert Fenn Sandy Thomson, Ex Officio John O’Dwyer Patrick Farrell Bruce MacRitchie, Ex Officio David G. Rohrer Art McCabe Nestor Yakimik, Ex Officio Barbara Maisonneuve David Williams Stay Connected Subscribe to our eFlyer Canadian Warplane warplane.com/mailing-list-signup.aspx Heritage Museum 9280 Airport Road Read Flightlines online warplane.com/about/flightlines.aspx Mount Hope, Ontario L0R 1W0 Like us on Facebook facebook.com/Canadian Phone 905-679-4183 WarplaneHeritageMuseum Toll free 1-877-347-3359 (FIREFLY) Fax 905-679-4186 Follow us on Twitter Email [email protected] @CWHM Web warplane.com Watch videos on YouTube youtube.com/CWHMuseum JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2019 Shop our Gift Shop warplane.com/gift-shop.aspx CANADIAN WARPLANE HERITAGE MUSEUM Follow Us on Instagram instagram.com/ canadianwarplaneheritagemuseum Volunteer Editor: Bill Cumming Flightlines is the official publication of the Canadian 80 GLORIOUS YEARS Canadian Warplane Heritage’s DC-3 Warplane Heritage Museum. It is a benefit of membership THE STORY OF SID BREGMAN And Spitfire MJ627 and is published six times per year (Jan/Feb, Mar/Apr, May/June, July/Aug, Sept/Oct, Nov/Dec). -

Daniel Egger Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c87w6jb1 Online items available Daniel Egger papers Finding aid prepared and updated by Gina C Giang. Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Fax: (626) 449-5720 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © Finding aid last updated June 2019. The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Daniel Egger papers mssEgger 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Daniel Egger papers Inclusive Dates: 1927-2019 Collection Number: mssEgger Collector: Egger, Daniel Frederic Extent: 3 boxes, 1 oversize folder, 1 flash drive, and 1 tube (1.04 linear feet) Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Fax: (626) 449-5720 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: The Daniel Egger papers include correspondence, printed matter, and photographs related to Daniel Egger’s career in the aerospace industry. Language of Material: The records are in English and Spanish. Access Collection is open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, please go to following web site . NOT AVAILABLE: The collection contains one flash drive, which is unavailable until reformatted. Please contact Reader Services for more information. RESTRICTED: Tube 1 (previously housed in Box 1, folder 1). Due to size of original, original will be available only with curatorial permission. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. -

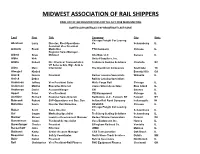

Midwest Association of Rail Shippers

MIDWEST ASSOCIATION OF RAIL SHIPPERS FINAL LIST OF 469 REGISTRATIONS FOR THE JULY 2018 MARS MEETING SORTED ALPHABETICALLY BY REGISTRANT LAST NAME Last First Title Company City State Chicago Freight Car Leasing Abraham Larry Director, Fleet Operations Co. Schaumburg IL Assistant Vice President Adcock Frank Marketing TTX Company Chicago IL Regional Sales Manager - Albert Greg Midwest Alta Max, LLC Geneva IL Albin Kirk United Suppliers, Inc. Aliota Robert Dir. Chemical Transportation Trelleborg Sealing Solutions Charlotte NC VP Sales & Grp. Mgr. Auto & Allen Marc Intermodal The Greenbrier Companies Southlake TX Almajed Khaled Beverly Hills CA Amick Dennis President Railcar Leasing Specialists Wilmette IL Amick Debra Railcar Leasing Specialists Anderson Jeffrey Vice President Sales Wells Fargo Rail Chicago IL Anderson Martha Executive Director James Street Associates Blue Island IL Anderson David Account Manger CN Geneva IL Appel Peter Vice President ITE Management Chicago IL Aseltine Richard Regional Sales Director RailComm, LLC - Fairport, NY Fairport NY Babcock Robert SVP-Operations and Bus. Dev. Indiana Rail Road Company Indianapolis IN Bahnline Kevin Director Rail Marketing RESDICO Chicago IL Chicago Freight Car Leasing Baker Scott Sales Director Co. Schaumburg IL Bal Gagan Marketing Specialist Trelleborg Sealing Solutions Schaumburg IL Banker Steven Logistics Development Manager Badger Mining Corporation Pulaski WI Bannerman Jayme Trackmobile Specialist Voss Equipment, Inc. Harvey IL Barenfanger Charles President Effingham Railroad -

CAA - Airworthiness Approved Organisations

CAA - Airworthiness Approved Organisations Category BCAR Name British Balloon and Airship Club Limited (DAI/8298/74) (GA) Address Cushy DingleWatery LaneLlanishen Reference Number DAI/8298/74 Category BCAR Chepstow Website www.bbac.org Regional Office NP16 6QT Approval Date 26 FEBRUARY 2001 Organisational Data Exposition AW\Exposition\BCAR A8-15 BBAC-TC-134 ISSUE 02 REVISION 00 02 NOVEMBER 2017 Name Lindstrand Technologies Ltd (AD/1935/05) Address Factory 2Maesbury Road Reference Number AD/1935/05 Category BCAR Oswestry Website Shropshire Regional Office SY10 8GA Approval Date Organisational Data Category BCAR A5-1 Name Deltair Aerospace Limited (TRA) (GA) (A5-1) Address 17 Aston Road, Reference Number Category BCAR A5-1 Waterlooville Website http://www.deltair- aerospace.co.uk/contact Hampshire Regional Office PO7 7XG United Kingdom Approval Date Organisational Data 30 July 2021 Page 1 of 82 Name Acro Aeronautical Services (TRA)(GA) (A5-1) Address Rossmore38 Manor Park Avenue Reference Number Category BCAR A5-1 Princes Risborough Website Buckinghamshire Regional Office HP27 9AS Approval Date Organisational Data Name British Gliding Association (TRA) (GA) (A5-1) Address 8 Merus Court,Meridian Business Reference Number Park Category BCAR A5-1 Leicester Website Leicestershire Regional Office LE19 1RJ Approval Date Organisational Data Name Shipping and Airlines (TRA) (GA) (A5-1) Address Hangar 513,Biggin Hill Airport, Reference Number Category BCAR A5-1 Westerham Website Kent Regional Office TN16 3BN Approval Date Organisational Data Name -

Canada's Privatization of Military Ammunition Production

CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS This PDF document was made available CIVIL JUSTICE from www.rand.org as a public service of EDUCATION the RAND Corporation. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE Jump down to document6 INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS POPULATION AND AGING The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit PUBLIC SAFETY research organization providing SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY SUBSTANCE ABUSE objective analysis and effective TERRORISM AND solutions that address the challenges HOMELAND SECURITY facing the public and private sectors TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE around the world. U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Lessons from the North Canada’s Privatization of Military Ammunition Production W. MICHAEL HIX BRUCE HELD ELLEN M. PINT Prepared for the Office of the Secretary of Defense Approved for public release, distribution unlimited The research described in this report was sponsored by the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD). -

Rudy Arnold Photo Collection

Rudy Arnold Photo Collection Kristine L. Kaske; revised 2008 by Melissa A. N. Keiser 2003 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Black and White Negatives....................................................................... 4 Series 2: Color Transparencies.............................................................................. 62 Series 3: Glass Plate Negatives............................................................................ 84 Series : Medium-Format Black-and-White and Color Film, circa 1950-1965.......... 93 -

Inside Stories BOLINGBROKE on FLOATS

Inside Stories BOLINGBROKE ON FLOATS Robert S Grant reveals how an example of the Canadian-built Bristol Blenheim – the Bolingbroke – was temporarily converted for waterborne trials t’s strange how a British Type 142, constructed to his In November 1937, what was a Inewspaper proprietor could specifications, drew RAF interest leisurely peacetime workshop affect seaplane operations in and eventually led to the newly began steps that would turn the a faraway country such as Canada. designated Type 149 Blenheim company into one of the largest This is exactly what happened Mk.I’s maiden flight on June aircraft builders in Canada. Hubert when Daily Mail owner Harold 25, 1936, at Filton, near Bristol. M Pasmore, president of Fairchild Sidney Harmsworth, 1st Viscount The light twin-engined bomber Aircraft’s Canadian subsidiary in Rothermere, decided to acquire advanced to the Bolingbroke Longueuil near Montréal, Québec a personal transport in 1934. The variant, which also flew its initial knew the Royal Canadian Air Force Bristol Aeroplane Company’s trip at Filton. (RCAF) was seeking a 88 FlyPast May 2020 maritime patrol aircraft. An astute patrol saltwater coasts, leading to that better results will be obtained businessman and pioneer pilot, proposals to convert Bolingbrokes if the Edo Company or MacDonald !" $% & The RCAF’s Pasmore lobbied on both sides of to seaplane configuration. Brothers is given an opportunity to Flt Lt A O Adams the Atlantic for an agreement to Unfortunately, few knew the do this work,” said Fairchild’s general expressed his belief that the Bolingbroke’s licence-build an initial batch of 18 difference between metal- manager N F Vanderlipp, who added: wing centre Bolingbrokes. -

Flightlines-JANUARY-2017.Pdf

SHOP ONLINE @ warplane.com Questions? Call: 905-679-4183 ext. 232 or GIFT SHOP Email: [email protected] President & Chief Executive Officer David G. Rohrer AVIATION Vice President – Curator Education Services Operations Erin Napier Manager Pam Rickards Howard McLean PHOTOGRAPHY Flight Coordinator Vice President – Finance Laura Hassard-Moran Donor Services Ernie Doyle Manager Retail Manager Sally Melnyk Chief Engineer Shawn Perras Jim Van Dyk Building Maintenance A presentation by Volunteer Coordinator Manager Eric Dumigan of his many Marketing Manager Toni McFarlane Jason Pascoe Al Mickeloff air-to-air images & stories! Controller Food & Beverage Facilities Manager Brenda Shelley Manager Cathy Dowd Steven Evangalista Board of Directors Christopher Freeman, Chair Nestor Yakimik Art McCabe David Ippolito Robert Fenn Dennis Bradley, Ex Officio John O’Dwyer Marc Plouffe Sandy Thomson, Ex Officio David G. Rohrer Patrick Farrell Bruce MacRitchie, Ex Officio Stay Connected Subscribe to our eFlyer warplane.com/mailing-list-signup.aspx Read Flightlines online warplane.com/about/flightlines.aspx Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum 9280 Airport Road Like us on Facebook Mount Hope, Ontario L0R 1W0 facebook.com/Canadian WarplaneHeritageMuseum Phone 905-679-4183 Toll free 1-877-347-3359 (FIREFLY) Follow us on Twitter Fax 905-679-4186 @CWHM Email [email protected] Web warplane.com Watch videos on YouTube youtube.com/CWHMuseum Shop our Gift Shop SATURDAY JANUARY 28, 2017 warplane.com/gift-shop.aspx Volunteer Editor: Bill Cumming 1:00 pm Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum Flightlines is the official publication of the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum. It is a benefit of Regular admission rates apply membership and is published six times per year (Jan/Feb, Mar/Apr, May/June, July/Aug, Sept/Oct, Nov/Dec). -

L'aérospatiale

Examen de l’aérospatiale Mandaté par le gouvernement du Canada Volume 1 Au-delà de l’horizon : les intérêts et l’avenir du Canada dans L’AÉROSPATIALE Novembre 2012 www.examenaerospatiale.ca Photo de la page couverture : ©Bombardier 1997-2012 Pour obtenir une version imprimée de cette publication, s’adresser aux : Éditions et Services de dépôt Travaux publics et Services gouvernementaux Canada Ottawa (Ontario) K1A 0S5 Téléphone (sans frais) : 1-800-635-7943 (au Canada et aux États-Unis) Téléphone (appels locaux) : 613-941-5995 Téléscripteur : 1-800-465-7735 Télécopieur (sans frais) : 1-800-565-7757 (au Canada et aux États-Unis) Télécopieur (envois locaux) : 613-954-5779 Courriel : [email protected] Site Web : www.publications.gc.ca On peut obtenir cette publication sur supports accessibles (braille et gros caractères), sur demande. Communiquer avec les : Services multimédias Direction générale des communications et du marketing Industrie Canada Courriel : [email protected] Cette publication est également offerte par voie électronique en version HTML (www.examenaerospatiale.ca). Autorisation de reproduction À moins d’indication contraire, l’information contenue dans cette publication peut être reproduite, en tout ou en partie et par quelque moyen que ce soit, sans frais et sans autre permission d’Industrie Canada, pourvu qu’une diligence raisonnable soit exercée afin d’assurer l’exactitude de l’information reproduite, qu’Industrie Canada soit mentionné comme organisme source et que la reproduction ne soit présentée ni comme une version officielle ni comme une copie ayant été faite en collaboration avec Industrie Canada ou avec son consentement. Pour obtenir l’autorisation de reproduire l’information contenue dans cette publication à des fins commerciales, faire parvenir un courriel à [email protected]. -

CATALINA 84 REV 23A C13 FINAL PRINT C552 141015.Cdr

ISSUE No 84 - AUTUMN/WINTER 2015 A fantastic view of Miss Pick Up overflying Operation World First's Faxa Sø lake site in Greenland during July this year. Expedition Leader Neal Gwynne is standing on the shoreline. Read more about this special event inside Alan Halewood £1.75 (free to members) PHOTOPAGE DOWN BY THE SEASIDE IN 2015 Several of our display commitments during 2015 were at seafront locations and here are photos taken at one of them – Llandudno in North Wales. Our back cover shows the excellent publicity poster for the show featuring a certain well- known flying boat! Often, local topography combined with a long focal length lens can produce unusual perspectives such as this one taken at the May display. Most of the crowd are out of view on the prom’ This view shows Miss Pick Up down low over the sea during its run in toward the crowd line – it could almost be the North Sea in 1945! 2 ISSUE No 84 - AUTUMN/WINTER 2015 EDITORIAL ADDRESSES Editor Membership & Subs Production Advisor David Legg Trevor Birch Russell Mason 4 Squires Close The Catalina Society 6 Lower Village Road Crawley Down Duxford Airfield Sunninghill Crawley Cambs Ascot West Sussex CB22 4QR Berkshire RHI0 4JQ ENGLAND SL5 7AU ENGLAND ENGLAND Editor: [email protected] Web Site: www.catalina.org.uk Webmaster: Mike Pinder Operations Web Site: www.catalinabookings.org The Catalina News is published twice a year by the Catalina Society and is for private circulation only within the membership of the Society and interested parties, copyright of The Catalina Society with all rights reserved.