Number 5 Bombing and Gunnery School Dafoe, Saskatchewan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story of Sid Bregman 80 Glorious Years

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2019 CANADIAN WARPLANE HERITAGE MUSEUM 80 GLORIOUS YEARS Canadian Warplane Heritage’s DC-3 THE STORY OF SID BREGMAN And Spitfire MJ627 President & Chief Executive Officer David G. Rohrer Vice President – External Client Services Manager Controller Operations Cathy Dowd Brenda Shelley Sandra Price Curator Education Services Vice President – Finance Erin Napier Manager Ernie Doyle Howard McLean Flight Coordinator Chief Engineer Laura Hassard-Moran Donor Services Jim Van Dyk Manager Retail Manager Sally Melnyk Marketing Manager Shawn Perras Al Mickeloff Building Maintenance Volunteer Services Manager Food & Beverage Manager Administrator Jason Pascoe Anas Hasan Toni McFarlane Board of Directors Christopher Freeman, Chair David Ippolito Robert Fenn Sandy Thomson, Ex Officio John O’Dwyer Patrick Farrell Bruce MacRitchie, Ex Officio David G. Rohrer Art McCabe Nestor Yakimik, Ex Officio Barbara Maisonneuve David Williams Stay Connected Subscribe to our eFlyer Canadian Warplane warplane.com/mailing-list-signup.aspx Heritage Museum 9280 Airport Road Read Flightlines online warplane.com/about/flightlines.aspx Mount Hope, Ontario L0R 1W0 Like us on Facebook facebook.com/Canadian Phone 905-679-4183 WarplaneHeritageMuseum Toll free 1-877-347-3359 (FIREFLY) Fax 905-679-4186 Follow us on Twitter Email [email protected] @CWHM Web warplane.com Watch videos on YouTube youtube.com/CWHMuseum JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2019 Shop our Gift Shop warplane.com/gift-shop.aspx CANADIAN WARPLANE HERITAGE MUSEUM Follow Us on Instagram instagram.com/ canadianwarplaneheritagemuseum Volunteer Editor: Bill Cumming Flightlines is the official publication of the Canadian 80 GLORIOUS YEARS Canadian Warplane Heritage’s DC-3 Warplane Heritage Museum. It is a benefit of membership THE STORY OF SID BREGMAN And Spitfire MJ627 and is published six times per year (Jan/Feb, Mar/Apr, May/June, July/Aug, Sept/Oct, Nov/Dec). -

CAA - Airworthiness Approved Organisations

CAA - Airworthiness Approved Organisations Category BCAR Name British Balloon and Airship Club Limited (DAI/8298/74) (GA) Address Cushy DingleWatery LaneLlanishen Reference Number DAI/8298/74 Category BCAR Chepstow Website www.bbac.org Regional Office NP16 6QT Approval Date 26 FEBRUARY 2001 Organisational Data Exposition AW\Exposition\BCAR A8-15 BBAC-TC-134 ISSUE 02 REVISION 00 02 NOVEMBER 2017 Name Lindstrand Technologies Ltd (AD/1935/05) Address Factory 2Maesbury Road Reference Number AD/1935/05 Category BCAR Oswestry Website Shropshire Regional Office SY10 8GA Approval Date Organisational Data Category BCAR A5-1 Name Deltair Aerospace Limited (TRA) (GA) (A5-1) Address 17 Aston Road, Reference Number Category BCAR A5-1 Waterlooville Website http://www.deltair- aerospace.co.uk/contact Hampshire Regional Office PO7 7XG United Kingdom Approval Date Organisational Data 30 July 2021 Page 1 of 82 Name Acro Aeronautical Services (TRA)(GA) (A5-1) Address Rossmore38 Manor Park Avenue Reference Number Category BCAR A5-1 Princes Risborough Website Buckinghamshire Regional Office HP27 9AS Approval Date Organisational Data Name British Gliding Association (TRA) (GA) (A5-1) Address 8 Merus Court,Meridian Business Reference Number Park Category BCAR A5-1 Leicester Website Leicestershire Regional Office LE19 1RJ Approval Date Organisational Data Name Shipping and Airlines (TRA) (GA) (A5-1) Address Hangar 513,Biggin Hill Airport, Reference Number Category BCAR A5-1 Westerham Website Kent Regional Office TN16 3BN Approval Date Organisational Data Name -

Aviation Historical Society of Australia

f . / .. / Aviation Historical Society OF Australia annual subscription £A1 : 10 : 0 Registered in Australia for transmission by post as a periodical ■ VOL. V No. 1 JANUARY 1964 EDITORIAL At the end of each year it is customary for the retiring Editor-in-Chief to give acknowledgement to the members who have assisted in the preparation and dis tribution of the AHSA Journal, Very few members are aware of the amount of work required to produce the Journal and it is with considerable pleasure that the Editor thanks the following for their efforts in 1963 j- Neil Follett for preparation of the Monthly Notes section and printing photo graphs with Garry Field for the photopagesj John Hopton for preparation of the Article Section and Index and Graham Hayward and his brother for distri bution of the Journal, The Journal is printed by Hr, Mai O'Brien of Rowprint Services and the photo- page'by J.G.Holmes Ltd*each have consistently supplied high quality work and have contributed to maintaining the standard of the Journal. The members whose names have appeared in the relevant issues for supplying notes and or articles together with the generous a-ssistancej from the Dep artments of Civil Aviation and Air and from the airlines, has made the work of the Editors much easier and is .deeply appreciatedo Without all of these contributions' there could riot be a Journal, Unfortunately it is not always possible for each member to devote the same amount of time to Journal preparation and due to this the Committee is always endeavouring to obtain regular assistance for this work from members, There seems to be a dearth of offers for this and it is largely for this reason that the present delay is due,■ Some thought has been given to transferring the Editor and Secretary positions to other States but ,it is not considered to be practical at this stage. -

Hail Thesuper Scooter

LEGACY PROFILE // A-4 SKYHAWK HAIL THESUPER SCOOTER HE TIME-WORN PHRASE, ‘It’s with uprated engines and equipment, By the end of the 1940s, the US Navy Above: A view of a single-seat Skyhawk not the size of the dog in the often helping to nurture indigenous needed both a replacement for the A-1 from a two-seat TA-4 fight, but the size of the fight aviation industries as a direct result. Skyraider and a machine to carry some of All images DoD in the dog’, perfectly sums From its roots as a replacement for the the new, lighter-weight nuclear weapons up the McDonnell-Douglas A-1 Skyraider on the decks of US carriers, that were then in development. A-4 Skyhawk, which was one the Skyhawk blossomed: a lightweight Twarplane that truly belied its size. and relatively inexpensive attack aircraft (it Genius and genesis Measuring a shade over 40ft in length cost around a quarter of the price of an F-4 Military jet aircraft – even those aboard and with a wingspan of just 27ft 6ins (so Phantom II), it was to become a nuclear the navy’s carrier decks – were getting small that no wing-fold mechanism was bomber, a tanker aircraft and it would also heavier and more complex and one required for storage on even the smallest be an ‘Iron Hand’ machine to tackle surface talented aircraft designer felt this shouldn’t carrier deck), this diminutive jet – quickly to air missile sites. necessarily be the case. nicknamed ‘Scooter’ – would give stellar Later, it would be transformed into Edward H Heinemann was chief designer service to the United States Navy and a two-seat training jet in which many at Douglas, despite never having a formal Marine Corps for 47 years. -

Inside Stories BOLINGBROKE on FLOATS

Inside Stories BOLINGBROKE ON FLOATS Robert S Grant reveals how an example of the Canadian-built Bristol Blenheim – the Bolingbroke – was temporarily converted for waterborne trials t’s strange how a British Type 142, constructed to his In November 1937, what was a Inewspaper proprietor could specifications, drew RAF interest leisurely peacetime workshop affect seaplane operations in and eventually led to the newly began steps that would turn the a faraway country such as Canada. designated Type 149 Blenheim company into one of the largest This is exactly what happened Mk.I’s maiden flight on June aircraft builders in Canada. Hubert when Daily Mail owner Harold 25, 1936, at Filton, near Bristol. M Pasmore, president of Fairchild Sidney Harmsworth, 1st Viscount The light twin-engined bomber Aircraft’s Canadian subsidiary in Rothermere, decided to acquire advanced to the Bolingbroke Longueuil near Montréal, Québec a personal transport in 1934. The variant, which also flew its initial knew the Royal Canadian Air Force Bristol Aeroplane Company’s trip at Filton. (RCAF) was seeking a 88 FlyPast May 2020 maritime patrol aircraft. An astute patrol saltwater coasts, leading to that better results will be obtained businessman and pioneer pilot, proposals to convert Bolingbrokes if the Edo Company or MacDonald !" $% & The RCAF’s Pasmore lobbied on both sides of to seaplane configuration. Brothers is given an opportunity to Flt Lt A O Adams the Atlantic for an agreement to Unfortunately, few knew the do this work,” said Fairchild’s general expressed his belief that the Bolingbroke’s licence-build an initial batch of 18 difference between metal- manager N F Vanderlipp, who added: wing centre Bolingbrokes. -

Flightlines-JANUARY-2017.Pdf

SHOP ONLINE @ warplane.com Questions? Call: 905-679-4183 ext. 232 or GIFT SHOP Email: [email protected] President & Chief Executive Officer David G. Rohrer AVIATION Vice President – Curator Education Services Operations Erin Napier Manager Pam Rickards Howard McLean PHOTOGRAPHY Flight Coordinator Vice President – Finance Laura Hassard-Moran Donor Services Ernie Doyle Manager Retail Manager Sally Melnyk Chief Engineer Shawn Perras Jim Van Dyk Building Maintenance A presentation by Volunteer Coordinator Manager Eric Dumigan of his many Marketing Manager Toni McFarlane Jason Pascoe Al Mickeloff air-to-air images & stories! Controller Food & Beverage Facilities Manager Brenda Shelley Manager Cathy Dowd Steven Evangalista Board of Directors Christopher Freeman, Chair Nestor Yakimik Art McCabe David Ippolito Robert Fenn Dennis Bradley, Ex Officio John O’Dwyer Marc Plouffe Sandy Thomson, Ex Officio David G. Rohrer Patrick Farrell Bruce MacRitchie, Ex Officio Stay Connected Subscribe to our eFlyer warplane.com/mailing-list-signup.aspx Read Flightlines online warplane.com/about/flightlines.aspx Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum 9280 Airport Road Like us on Facebook Mount Hope, Ontario L0R 1W0 facebook.com/Canadian WarplaneHeritageMuseum Phone 905-679-4183 Toll free 1-877-347-3359 (FIREFLY) Follow us on Twitter Fax 905-679-4186 @CWHM Email [email protected] Web warplane.com Watch videos on YouTube youtube.com/CWHMuseum Shop our Gift Shop SATURDAY JANUARY 28, 2017 warplane.com/gift-shop.aspx Volunteer Editor: Bill Cumming 1:00 pm Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum Flightlines is the official publication of the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum. It is a benefit of Regular admission rates apply membership and is published six times per year (Jan/Feb, Mar/Apr, May/June, July/Aug, Sept/Oct, Nov/Dec). -

Fairey Swordfish

Last updated 1 December 2020 ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| FAIREY SWORDFISH |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| B.3593 • Mk. I W5856 built by Blackburn Aircraft at Sherburn-in-Elmet: ff 21.10.41 (Blackburn) RNFAA service in Mediterranean theatre 42/43 Fairey Aviation, Stockport: refurbished for Canada .43 Mk.IV (to RCAF as W5856): BOC 15.12.44: SOC 21.8.46 Mount Hope AB ONT: storage and disposal .45/46 Ernest K. Simmons, Tillsonburg ONT .46/70 (open storage on his farm, one of 12 derelict Swordfish sold at auction on the farm 5.9.70) J. F. Carter, Monroeville, Alabama: rest. began 9.70/76 Sir W. J. D. Roberts/ Strathallan Aircraft Collection, Auchterader, Scotland: arr. in crates 7.8.77/85 G-BMGC Strathallan Aircraft Collection, Auchterader 31.10.85/90 British Aerospace/ The Swordfish Heritage Trust 10.90/93 (by road to BAe Brough14.12.90 for rest. using wings from NF389, ff 12.5.93) RN Historic Flight, RNAS Yeovilton 22.5.93/20 (flew as "RN W5856/A2A City of Leeds", grounded 10.03, long-term rest. at Yeovilton, ff 19.6.15 repainted as “Royal Navy W5856/4A”) (RN Historic Flight officially disbanded 31.3.19) G-BMGC Fly Navy Heritage Trust/ Navy Wings. Yeovilton 17.3.20 -

Dropzone Issue 2

HARRINGTON AVIATION MUSEUMS HARRINGTON AVIATION MUSEUMS V OLUME 6 I SSUE 2 THE DROPZONE J ULY 2008 Editor: John Harding Publisher: Fred West MOSQUITO BITES INSIDE THIS ISSUE: By former Carpetbagger Navigator, Marvin Edwards Flying the ‘Mossie’ 1 A wooden plane, a top-secret mission and my part in the fall of Nazi Germany I Know You 3 Firstly (from John Harding) a few de- compared to the B-24. While the B- tails about "The Wooden Wonder" - the 24’s engines emitted a deafening roar, De Havilland D.H.98 Mosquito. the Mossie’s two Rolls Royce engines Obituary 4 seemed to purr by comparison. Al- It flew for the first time on November though we had to wear oxygen masks Editorial 5 25th,1940, less than 11 months after due to the altitude of the Mossie’s the start of design work. It was the flight, we didn’t have to don the world's fastest operational aircraft, a heated suits and gloves that were Valencay 6 distinction it held for the next two and a standard for the B-24 flights. Despite half years. The prototype was built se- the deadly cold outside, heat piped in Blue on Blue 8 cretly in a small hangar at Salisbury from the engines kept the Mossie’s Hall near St.Albans in Hertfordshire cockpit at a comfortable temperature. Berlin Airlift where it is still in existence. 12 Only a handful of American pilots With its two Rolls Royce Merlin en- flew in the Mossie. Those who did had gines it was developed into a fighter some initial problems that required and fighter-bomber, a night fighter, a practice to correct. -

'For Your Tomorrow'

‘For Your Tomorrow’ Anzacs laid to rest in India Compiled by the Defence Section Australian High Commission, New Delhi with information or assistance from: Commonwealth War Graves Commission Defence Section, New Zealand High Commission Department of Veteran Affairs, Australia National Archives of Australia New Zealand Army Archives Royal New Zealand Air Force Museum Royal New Zealand Navy Museum Sqn Ldr (Retd)Rana T.S. Chhina, MBE - This edition published April 2021 – This work is Copyright © but may be downloaded, displayed, printed or reproduced in unaltered form for non-commercial use. 2 CONTENTS Foreword 4 Introduction 5 Map of Commonwealth War Cemeteries and 6 Memorials (Australians or New Zealanders registered) Roll of Honour 7 Biographies of the Fallen - First World War 10 a. Delhi Memorial (India Gate) 12 b. Deolali Government Cemetery 14 c. Kirkee 1914-1918 Memorial 16 Biographies of the Fallen - Second World War 21 d. Calcutta (Bhowanipore) Cemetery 30 e. Delhi War Cemetery 38 f. Gauhati War Cemetery 54 g. Imphal War Cemetery 60 h. Kirkee War Cemetery 69 i. Kohima War Cemetery 83 j. Madras War Cemetery 88 k. Ranchi War Cemetery 108 Commonwealth War Graves Commission 125 National War Memorial of India - New Delhi 126 3 Foreword This booklet provides an excellent insight into Australian and New Zealand service- personnel who died and were buried on Indian soil. There are ninety-one Anzacs from the First and Second World Wars buried in Commonwealth War Graves across India at nine locations including Delhi, Deolali, Imphal, Kohima, Ranchi, Chennai, Kolkata, Pune and Guwahati. From nurses who served in British hospitals in India, where their patients included Turkish prisoners of war and wounded British troops, to Air Force officers who died in action in major battles across India, including the battles of Kohima and Imphal. -

RCAF Aircraft Types

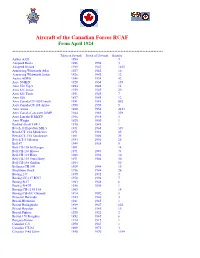

Aircraft of the Canadian Forces RCAF From April 1924 ************************************************************************************************ Taken on Strength Struck off Strength Quantity Airbus A320 1996 5 Airspeed Horsa 1948 1959 3 Airspeed Oxford 1939 1947 1425 Armstrong Whitworth Atlas 1927 1942 16 Armstrong Whitworth Siskin 1926 1942 12 Auster AOP/6 1948 1958 42 Avro 504K/N 1920 1934 155 Avro 552 Viper 1924 1928 14 Avro 611 Avian 1929 1945 29 Avro 621 Tutor 1931 1945 7 Avro 626 1937 1945 12 Avro Canada CF-100 Canuck 1951 1981 692 Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow 1958 1959 5 Avro Anson 1940 1954 4413 Avro Canada Lancaster X/MP 1944 1965 229 Avro Lincoln B MkXV 1946 1948 3 Avro Wright 1925 1930 1 Barkley-Grow T8P-1 1939 1941 1 Beech 18 Expeditor MK 3 1941 1968 394 Beech CT-13A Musketeer 1971 1981 25 Beech CT-13A Sundowner 1981 1994 25 Beech T-34 Mentor 1954 1956 25 Bell 47 1948 1965 9 Bell CH-139 Jet Ranger 1981 14 Bell CH-136 Kiowa 1971 1994 74 Bell CH-118 Huey 1968 1994 10 Bell CH-135 Twin Huey 1971 1994 50 Bell CH-146 Griffon 1994 99 Bellanca CH-300 1929 1944 13 Blackburn Shark 1936 1944 26 Boeing 247 1940 1942 8 Boeing CC-137 B707 1970 1994 7 Boeing B-17 1943 1946 6 Boeing B-47B 1956 1959 1 Boeing CH-113/113A 1963 18 Boeing CH-47C Chinook 1974 1992 8 Brewster Bermuda 1943 1946 3 Bristol Blenheim 1941 1945 1 Bristol Bolingbroke 1939 1947 626 Bristol Beaufort 1941 1945 15 Bristol Fighter 1920 1922 2 Bristol 170 Freighter 1952 1967 6 Burguss-Dunne 1914 1915 1 Canadair C-5 1950 1967 1 Canadair CX-84 1969 1971 3 Canadair F-86 Sabre -

Bermuda, Here We Come by Stan Brygadyr

Spring 2021 Bermuda, Here we Come by Stan Brygadyr It was a dark and stormy night, but we had to go to Bermuda, as a Royal Navy “A” Boat (submarine) was waiting for us to do Anti-Submarine (ASW) training. It was 25 Nov 1961, and my Commanding Officer (CO, VS-880 Sqn) was to lead a 4-plane formation of Tracker aircraft. I was his co-pilot (and thus the “lead navigator”). Navigating the 750nm to Bermuda, straight South of Halifax, was not normally a problem provided you stayed at 1000ft or below under Visual Flight Rules (VFR), in order to see the “wind-lanes” on the water surface and thus estimate the wind-speed and direction (this is “dead-reckoning” navigation). The Tracker was not equipped with any long- range navigation capability, only a low-frequency radio for airways beacons, and tactical air navigation (TACAN), for both airways and relative position to the carrier. The expected morning departure was stymied by thick fog at our home base of Shearwater NS, and it didn’t open up for an Instrument flight departure until late afternoon. Since we were now going for a night flight, and not VFR (so no formation!), we had to file an Oceanic flight plan individually, and we departed “stacked” at 9,8,7 and 6000 ft. Now came the challenge! The weather forecaster advised of a frontal system along the route, and winds at the start would be WSW at about 20kts. I therefore biased our heading slightly west of the required track; there was no ability once airborne to assess the wind direction or speed! After about 4 hours airborne, and being in severe thunderstorm activity which produced St Elmo’s Fire on our windscreen (which was a new experience for me and scary as hell!), we should have been able to receive the Bermuda Beacon or TACAN. -

Over 400 Aircraft Engines 1/32 1/48 1/72 Scale September 2020

ENGINES & THINGS OVER 400 AIRCRAFT ENGINES 1/32 1/48 1/72 SCALE SEPTEMBER 2020 BRITISH NORTH AMERICAN FRENCH GERMAN RUSSIAN JAPANESE ITALIAN JET ENGINES PRATT & WHITNEY R-2800 SERIES Page 8 ACCURATE, DETAILED, CAST RESIN ENGINES NO BACK ORDERS WITHIN 3 DAY SERVICE INDIVIDUALLY CAST & PACKAGED PHONE: (780) 997-9919 E-MAIL & PAYPAL: [email protected] EMAIL OR CALL IF PAYING BY CHEQUE. WEBSITE: www.enginesandthings.com ENGINES & THINGS Products are listed alphabetically by country CW - Curtiss Wright P&W = Pratt & Whitney HP = Handley Page D.D. = Direct Drive 1:48 SCALE ENGINES Code NORTH AMERICAN Price U.S. 48013 Allison T-56 turbine for C-130 Hercules, E-2 Hawkeye, Greyhound, C-123T,CZA, detailed cowling information $ 14.00 48177 Allison V-1710 C Series (long nose, early) for Lockheed XP-38, 322F, B, P-322, YP-37, early P-40 long nose, small radiator, XP-40, P-40B $ 10.00 48178 Allison V-1710 E Series, shaft driven reduction gearbox for P-400, XP-39, YP-39, P-39,C,D,F,J,K,M,N,L,Q $10.00 48179 Allison V-1710 F Series for P-40C,D,E,G,K,M,N,R, P-51,A,A-36, early P-51B's, P-82, XP-55,46,40,40Q, North American N-73,F6A,F-82F,6H $10.00 48180 Allison V-1710 F Series for P-38,D,E,H,J,K,L,M, F-4,5,6 $ 10.00 48181 Allison V-1710-93 for MPM-P-63A,C King Cobra $ 12.00 48042 Continental 0-470 185 hp for Cessna Bird Dog C-180 $ 8.00 48119 Continental R-670 7 cyl.