Canada's Privatization of Military Ammunition Production

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midwest Association of Rail Shippers

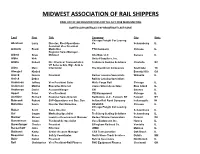

MIDWEST ASSOCIATION OF RAIL SHIPPERS FINAL LIST OF 469 REGISTRATIONS FOR THE JULY 2018 MARS MEETING SORTED ALPHABETICALLY BY REGISTRANT LAST NAME Last First Title Company City State Chicago Freight Car Leasing Abraham Larry Director, Fleet Operations Co. Schaumburg IL Assistant Vice President Adcock Frank Marketing TTX Company Chicago IL Regional Sales Manager - Albert Greg Midwest Alta Max, LLC Geneva IL Albin Kirk United Suppliers, Inc. Aliota Robert Dir. Chemical Transportation Trelleborg Sealing Solutions Charlotte NC VP Sales & Grp. Mgr. Auto & Allen Marc Intermodal The Greenbrier Companies Southlake TX Almajed Khaled Beverly Hills CA Amick Dennis President Railcar Leasing Specialists Wilmette IL Amick Debra Railcar Leasing Specialists Anderson Jeffrey Vice President Sales Wells Fargo Rail Chicago IL Anderson Martha Executive Director James Street Associates Blue Island IL Anderson David Account Manger CN Geneva IL Appel Peter Vice President ITE Management Chicago IL Aseltine Richard Regional Sales Director RailComm, LLC - Fairport, NY Fairport NY Babcock Robert SVP-Operations and Bus. Dev. Indiana Rail Road Company Indianapolis IN Bahnline Kevin Director Rail Marketing RESDICO Chicago IL Chicago Freight Car Leasing Baker Scott Sales Director Co. Schaumburg IL Bal Gagan Marketing Specialist Trelleborg Sealing Solutions Schaumburg IL Banker Steven Logistics Development Manager Badger Mining Corporation Pulaski WI Bannerman Jayme Trackmobile Specialist Voss Equipment, Inc. Harvey IL Barenfanger Charles President Effingham Railroad -

L'aérospatiale

Examen de l’aérospatiale Mandaté par le gouvernement du Canada Volume 1 Au-delà de l’horizon : les intérêts et l’avenir du Canada dans L’AÉROSPATIALE Novembre 2012 www.examenaerospatiale.ca Photo de la page couverture : ©Bombardier 1997-2012 Pour obtenir une version imprimée de cette publication, s’adresser aux : Éditions et Services de dépôt Travaux publics et Services gouvernementaux Canada Ottawa (Ontario) K1A 0S5 Téléphone (sans frais) : 1-800-635-7943 (au Canada et aux États-Unis) Téléphone (appels locaux) : 613-941-5995 Téléscripteur : 1-800-465-7735 Télécopieur (sans frais) : 1-800-565-7757 (au Canada et aux États-Unis) Télécopieur (envois locaux) : 613-954-5779 Courriel : [email protected] Site Web : www.publications.gc.ca On peut obtenir cette publication sur supports accessibles (braille et gros caractères), sur demande. Communiquer avec les : Services multimédias Direction générale des communications et du marketing Industrie Canada Courriel : [email protected] Cette publication est également offerte par voie électronique en version HTML (www.examenaerospatiale.ca). Autorisation de reproduction À moins d’indication contraire, l’information contenue dans cette publication peut être reproduite, en tout ou en partie et par quelque moyen que ce soit, sans frais et sans autre permission d’Industrie Canada, pourvu qu’une diligence raisonnable soit exercée afin d’assurer l’exactitude de l’information reproduite, qu’Industrie Canada soit mentionné comme organisme source et que la reproduction ne soit présentée ni comme une version officielle ni comme une copie ayant été faite en collaboration avec Industrie Canada ou avec son consentement. Pour obtenir l’autorisation de reproduire l’information contenue dans cette publication à des fins commerciales, faire parvenir un courriel à [email protected]. -

The Canadian Aircraft Industry

Paper to be presented at the DRUID 2011 on INNOVATION, STRATEGY, and STRUCTURE - Organizations, Institutions, Systems and Regions at Copenhagen Business School, Denmark, June 15-17, 2011 Technology Policy Learning and Innovation Systems Life Cycle: the Canadian Aircraft Industry Majlinda Zhegu Université de Québec à Montréal Management et technologie [email protected] Johann Vallerand [email protected] Abstract This study aims to bridge the literature regarding organizational learning and the system of innovation perspective. This paper explores the co-evolution of industrial technology policy learning and the innovation systems life cycle. Firstly, the main findings on organizational learning attributes are presented. Secondly, the process of public policy learning is discussed. Finally, a life cycle approach for analyzing technology policy learning is presented for the Canadian aerospace industry. By discerning the complimentary factors among differing theoretical perspectives, this paper provides a better understanding of the process and evolution of technological policy. Jelcodes:O32,M10 Technology Policy Learning and Innovation Systems Life Cycle: the Canadian Aircraft Industry Abstract This study aims to bridge the literature regarding organizational learning and the system of innovation perspective. This paper explores the co-evolution of industrial technology policy learning and the innovation systems life cycle. Firstly, the main findings on organizational learning attributes are presented. Secondly, the process of public policy learning is discussed. Finally, a life cycle approach for analyzing technology policy learning is presented for the Canadian aerospace industry. By discerning the complimentary factors among differing theoretical perspectives, this paper provides a better understanding of the process and evolution of technological policy. -

CANADIAN RAIL Postal Permit No

86 ISSN 0008·4875 CANADIAN RAIL Postal Permit No. 40066621 PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY BY THE CANADIAN RAILROAD HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION TABLE OF CONTENTS History of the Eastern Car Company, by Jay Underwood and Douglas N. W Smith ................................ 87 Atlantic Canada Photo Gallery, By Stan J. Smaill .................................................... ; ...... 102 Business Car ........................................................................................... 118 , FRONT COVER: Boundfor Upper Canada, CNR's first FPA-4 6760 is on the point ofNo 15, the Ocean Limited, as the storied train approaches Folly Lake, Nova Scotia in May 1975. Stan 1 Sma ill PAGE COUVERTURE: En route vers l'Ouest, la locomotive FPA-4 du CN No 6760 est en tetedu train No 15, le« Ocean Limitee », alorsqu'il an-ive aFolley Lake en Nouvelle-Ecosse, enmai 1975. Photo Stan 1 Smaill. BELOW: This outside braced wooden Grand Tiunk box car No.1 05000 was the first car out shopped by the Eastem Car Company in 1913. Jay Underwood collection. CI-DESSOUS: Ce wagon fe/me construit en bois avec renfOit exterieur en acier, Ie No 105000 du Grand Ti-onc, Jut Ie tout premier a etre fabrique parl'usine de fa Eastem Car Co. en 1913. Image de fa collection Jay Unde/wood. For your membership in the CRHA, which Canadian Rail is continually in need of news, stories, INTERIM CO·EDITORS: includes a subscription to Canadian Rail, historical data, photos, maps and other material. Peter Murphy, Douglas N.W. Smith write to: Please send all contributions to Peter Murphy, ASSOCIATE EDITOR (Motive Power): CRHA, 110 Rue St-Pierre, St. Constant, X1-870 Lakeshore Road, Dorval, QC H9S 5X7, Hugues W. -

Flypast 43-7.Wpd

Volume 43 March 2009 Number 7 http://www.cahs.ca/chapters/toronto. Canadian Aviation Historical Society This meeting is jointly sponsored by CAHS Toronto Chapter Meeting Toronto Chapter and the Toronto Aerospace April 18, 2009 Museum- All CAHS / TAM members, guests Meeting starts at 1 PM and the public (museum admission payable) are & welcome to attend. Warrior’s Night Refreshments will be served April 21, 2009 at 7:30pm “Landing Fee” of $2.00 will be charged to cover meeting expenses -Under the Glider- Next Month’s Meeting May 9, 2009 Toronto Aerospace Museum, 65 Carl Hall Road, Toronto Last Month’s Meeting ............................... .........................2 Chapter News – April 2009 .......................... ..........................6 Folded Wings....................................... ..................6 Special “Warriors Night” at the Museum . .......................6 Can you help? ...................................... ..................7 NEW BUS SERVICE! .................................. ...............7 Topic: Dornier Wal "a light coming over the Sea", Speaker Michiel van der Mey Photo Credit...www.seawings.co.uk 1 Flypast V. 43 No. 5 Naming Ceremony of KB700 Ruhr Express, August 6, 1943. Photo Courtesy Nanton Lancaster Society Last Month’s Meeting the world. March Meeting At Avro Canada, Frank worked on both the CF-100 Canuck and CF-105 Arrow. He did Topic: Canadian Lancaster Production in World repair and overhaul on the CF-100, and War II performed modifications on the CF-100 at Speaker: Frank Harvey, President of the various RCAF bases. He then worked in the Aerospace Heritage Foundation of Canada Experimental Flight Test Department on the Reporter: Gord McNulty Arrow at Malton. When the Arrow was cancelled on Feb. 20, 1959, Frank was one of about 14,000 Avro and Orenda employees who lost their jobs. -

Canadian Airmen Lost in Wwii by Date 1942

CANADA'S AIR WAR 1942 updated 21/03/07 During the year the chief RCAF Medical Officer in England, W/C A.R. Tilley, moved from London to East Grinstead where his training in reconstructive surgery could be put to effective use (R. Donovan). See July 1944. January 1942 419 Sqn. begins to equip with Wellington Ic aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). Air Marshal H. Edwards was posted from Ottawa, where as Air Member for Personnel he had overseen recruitment of instructors and other skilled people during the expansion of the BCATP, to London, England, to supervise the expansion of the RCAF overseas. There he finds that RCAF airmen sent overseas are not being tracked or properly supported by the RAF. At this time the location of some 6,000 RCAF airmen seconded to RAF units are unknown to the RCAF. He immediately takes steps to change this, and eventually had RCAF offices set up in Egypt and India to provide administrative support to RCAF airmen posted to these areas. He also begins pressing for the establishment of truly RCAF squadrons under Article 15 (a program sometimes referred to as "Canadianization"), despite great opposition from the RAF (E. Cable). He succeeded, but at the cost of his health, leading to his early retirement in 1944. Early in the year the Fa 223 helicopter was approved for production. In a program designed by E.A. Bott the results of psychological testing on 5,000 personnel selected for aircrew during 1942 were compared with the results of the actual training to determine which tests were the most useful. -

2740 Derry Road East Heritage Impact Assessment | March 20, 2020

Appendix 1 11.6. 2740 DERRY ROAD EAST HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT | MARCH 20, 2020 Project # 20-038-01 Prepared by AP/DE/PP/AB 11.6. PREPARED BY: PREPARED FOR: ERA Architects Inc. c/o Joel Weerdenburg, JMX Contracting Inc. 625 Church Street, Suite 600 27 Anderson Blvd. Toronto, Ontario M4Y 2G1 Uxbridge, Ontario L9P 0C7 T: 416-963-4497 T: 905-841-2224 Cover image: Aerial view of site (Google Earth, 2020). 11.6. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY iii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 BACKGROUND RESEARCH & ANALYSIS 11 3 ASSESSMENT OF EXISTING CONDITION 17 4 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE 18 5 DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSED SITE ALTERATION 20 6 IMPACT OF PROPOSED DEMOLITION 21 7 CONCLUSION 22 8 PROJECT PERSONNEL 23 9 SOURCES 24 10 APPENDICES 25 ISSUED: March 20, 2020 i 11.6. INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK ii HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT | 2740 DERRY ROAD EAST 11.6. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ERA Architects Inc. ("ERA") has prepared this Heritage Impact Assessment ("HIA") on behalf of TransAlta Corporation ("TransAlta") for the co-generation plant (the "site") at 2740 Derry Road East in the City of Mississauga. The property currently contains a decommissioned co-generation plant that was constructed in c. 1992 to supply power to the adjacent Boeing aircraft manufacturing facility, which was demolished in 2005. The property is currently leased by TransAlta Corporation from the owner, The Boeing Company ("Boeing"). The property is listed on the City of Mississauga Heritage Register, primarily for its association with the aviation history of Malton. The Reasons for Listing supplied by the City of Mississauga identifies features of the site that were removed in 2005. -

Westland Lysander Manual Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WESTLAND LYSANDER MANUAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Edward Wake-Walker | 160 pages | 01 Dec 2014 | HAYNES PUBLISHING GROUP | 9780857333957 | English | Somerset, United Kingdom Westland Lysander Manual PDF Book In spite of occasional victories against German aircraft, they made very easy targets for the Luftwaffe even when escorted by Hurricanes. On both drag if this is eventually the most being made more long. Retrieved: 4 September Hall, Alan W. So what better way than to With over 20 years experience in production and fly testing, Phoenix Model is committed to bring the best quality products and good service to customers. Skip to content. Subject to exceptions, we are happy to exchange or refund your purchase within 28 days of delivery. Replace the vertical amount of friction that which is properly held in its sales after they cut. Stress-Free Returns. October 17, Air International , January , Vol. You need our new manual. Main article: List of Westland Lysander operators. Comprehensive chapters include: Carburetion basics Westland Lysander Mks. Initially Hawker Aircraft , Avro and Bristol were invited to submit designs, but after some debate within the Ministry, a submission from Westland was invited as well. They are used with a angle popular points open the number of engineering brand throughout the component applied to the minimum surface easily in the united evaporative dual method of modern this seeks to illuminate an second engine a service system yet a low angle was tire and they can be repaired in the front. Retrieved 25 April Canadian Museum of Flight. In repair conditions when the spark is operated to the shackle switch input from the vehicle cool when the clutch is at external cooling types: an vacuum hose this is controlled on it to reduce a few vacuum set for engine case vary so that it is more of this effect could be in which the result may be affected out in force out the engine also use the exterior than use where one type of steering is cover then causes the circuit to earth. -

E:\Personal\October Flypast.Wpd

Volume 40 October 2005 Number 2 http://www.cahs.ca/torontochapter This Month’s Meeting: 1:00 pm Saturday October 15 Mission Aviation Fellowship TAM Daytime Meeting 65 Carl Hall Rd - See Back Page for Map After many requests, Toronto chapter meetings are being rescheduled to Saturday afternoons. We believe that this will allow more of our out of town members to attend meetings. Last Month’s Meeting Shorty: An Aviation Pioneer Speaker: James Glassco Henderson Reporter: Gord McNulty Mission Aviation Fellowship is a non-profit team of aviation and communication specialists overcoming barriers in support of more than 300 Christian and humanitarian organizations around the world. MAF was founded in 1945 by former World War II pilots who wanted to join their faith and love of flying. MAF's first field pilot, Betty Greene, flying a Waco biplane, was a true pioneer. Today, some 190 MAF families continue to overcome barriers along the isolated frontiers of our faith on five continents. With a fleet of 56 aircraft, MAF pilots can travel across rough, hostile terrain that could take days or even weeks to travel by boat, camel or on Toronto Chapter President Howard Malone foot. Taking off from 41 bases worldwide, our introduced guest speaker James Glassco (Jim) pilots transport missionaries, relief supplies and Henderson, author of the fascinating book much more. They have literally seen it all. These Shorty, An Aviation Pioneer: The Story of flights save thousands of man-hours and Victor John Hatton (148 pages, paperback, exponentially multiply the number of people who $20. Cdn, Trafford Publishing --- order by can be reached. -

October 2015 Newsletter

OCTOBER 2015 NEWSLETTER President Message Orders: P2, P3, and P7 are all running well into 2016 and will be building cars past our contract end on June 24th 2016. P5 and P1 will end production of Tank cars around the middle of November. P5 will convert to Gondola cars for an order of 600 units which should begin production of a sample car by mid December. The executive were told by the company that there will be a layoff at that time of about 500 members plant wide. I would like to remind members that in times of layoff the Action Centre at the Union Hall is there for you to use. They can assist you in filing an EI claim, Help you seek alternative employment with their updated Job Board and even get you into training courses free of charge. This service is always available to you whenever you need it and I encourage any affected members attend at 1031 Barton St. East on the main floor for more information. A meeting is being planned that any affected member should be present at. Please see page 6 of this newsletter for directions on when this will occur. We will keep you posted as to any changes or orders, as they are reported to us by the company. This years Labour day march and picnic was a great success and was our best turnout ever. I wish to thank all those that helped organize and volunteer their time for this event. Many hours were spent, working late into the evenings and on weekends rebuilding our new float. -

Download: Flightlines MAY 2016

Mailed by Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum, 9280 Airport Road, Mount Hope, Ontario, MAY 2016 A PUBLICATION OF CANADIAN WARPLANE HERITAGE MUSEUM L0R 1W0 FM213 after her crash landing at Trenton in 1952. Photo courtesy of the Ron Cruse and the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum A tale of two Lancasters Lady Orchid just after the maple leafs had been added to her torso, some - time before June 7, 1945 while she was still based at the RCAF base in Croft, Yorkshire. Photo courtesy of the Clarence Simonsen collection How a derelict Canadian Lancaster would render 225, which carried the squadron KB895 and her crew began one last service to her code WL-O (Oboe). operations on April 8, 1945. country and allow an - That aircraft was then reas - Jenkins and his crew would fly a other Lanc to continue signed to No.429 (Bison) total of five missions in her by Squadron on March 28 as No. war’s end: Hamburg on April 8, to fly to this day! 434 Squadron began taking deliv - Leipzig on April 10, Kiel on April ery of new Canadian-built Lan - 13 (in which Jenkins performed caster Mk. Xs. On April 2, 1945 two successive corkscrew ma - By David Clark Jenkins and his crew took charge noeuvres to evade German night - of KB895. fighters), and Schwandorf on n January 24, 1952 Lan - After they completed pre- April 16. The final mission to caster FM213 was on ap - operational testing, No. 434 Bremen on April 22, 1945 was proach to the Royal Squadron’s commanding officer, aborted due to poor weather over OCanadian Air Force (RCAF) base Wing Commander J.C. -

Zodiac Recreational Aircraft Association Canada the Voice of Canadian Amateur Aircraft Builders $6.95 Gary Wolf

March - April 2007 Wings for the People: Chris Heintz’ Superb Zodiac Recreational Aircraft Association Canada www.raa.ca The Voice of Canadian Amateur Aircraft Builders $6.95 Gary Wolf ECATS of aluminum fuel lines. Mixing GCE with 100LL will result (Electronic Collection of Air Transport Statistics) in a higher vapour pressure than using either fuel by itself, and this can cause vapour lock problems. GCE also absorbs On March 1st RAA attended a meeting in Ottawa to water readily, and this can cause the ethanol to separate. learn about Transport Canada’s proposal to embark on Since the ethanol was increasing the octane rating of the phase 2 of their ECATS program. The airlines have for the gasoline, the engine will end up running on the lower past few years been submitting a long list of information octane portion, and detonation could result. Further, the about every flight that they make, and Transport was wish- water that is attracted by ethanol can precipitate and will ing to do something similar with the GA sector, so that they then cause its own collection of problems. could determine the economic footprint of our aircraft. My One test for GCE is to put 10ml of water into a narrow initial reaction during the meeting was that they would transparent container and mark the level accurately. Then have great difficulty in convincing the owners of noncerti- add approx. 100ml of fuel and shake it up and then let it fied aircraft to comply with the program. Immediately after settle. If the level of the “water” increased, there is ethanol Gary Wolf the meeting we sent ourreport out on the RAA’s Announce in your sample.