The Canadian Aircraft Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By James Thompson

WARBIRDS WARBIRDS INTERNATIONAL WARBIRDS WARBIRDS WARBIRDS WARBIRDS WARBIRDS WARBIRDS WARBIRDS WARBIRDS WARBIRDS WARBIRDS WARBIRDS WARBIRDS AS NOTED ELSEWHERE IN THIS ISSUE, THE COLLINGS FOUNDATION IS ON A ROLL AND HAS JUST ACQUIRED A CATALINA BY JAMES The unusual sight of a Catalina (Canso) moving down THOMPSON public streets. rivers on the main Although it will require considerable work, the Canso road leaving St. will be restored back to flying condition. Hubert, Quebec, January 1953, it was back at AIL for Don 13 June were a bit astound- repairs to an excessive leak in the star- ed to see the shape of what looked like board fuel tank. a large yellow boat being moved by By this time, the Canso was flying truck. What they were viewing was the with No. 103 Rescue Unit at RCAF latest acquisition by the Collings Station Greenwood, Nova Scotia. On 8 Foundation — Consolidated/ May 1953, it was again flown to No. 6 Canadian Vickers Canso A RCAF RD for unspecified repairs that were This is how C-FPQK looked when in active service 9830 (or PBY Catalina in American!). with Quebec as a water-bomber and transport. completed in January 1954. However, This vintage amphibian had been on on 29 October 1954 it was flown to AIL display with the Foundation Aerovision Quebec at St. Hubert for repairs to the electrical system, modifications, and upgrades. since 1994. When delivered to that organization, the aircraft was On 11 March 1957, it was flown to No. 6 RD for installation of still airworthy but is not currently flyable. -

Bombardier Challenger 605

The Conklin & de Decker Report Bombardier Challenger 605 Created on August 21, 2019 by Doug Strangfeld © 2019 Conklin & de Decker Associates, Inc PO BOX 121184 1006 North Bowen, Suite B Arlington, TX 76012 www.conklindd.com Data version: V 19.1 Bombardier Challenger 605 RANGE 3,756 nm SPEED 488 kts PASSENGERS 10 people Cost ACQUISITION COST ANNUAL COST VARIABLE COST FIXED COST $15,000,000 $2,235,337 $3,218/hr $948,127 MAX PAYLOAD 4,850 lb ENGINES 2 General Electric CF34-3B TOTAL CABIN AREA 1,146 cu ft AVIONICS Collins Pro-Line 21 WINGSPAN 64.3 ft APU Standard Assumptions This report uses custom assumptions that differ from Conklin & de Decker default values for Annual Utilization (Hours), Fuel Price (Jet A). ANNUAL UTILIZATION (DISTANCE) 165,600 nm FUEL PRICE (JET A) $4.45/gal ANNUAL UTILIZATION (HOURS) 400 hrs LABOR COST $136/hr AVERAGE SPEED (STANDARD TRIP) 414 kts ACQUISITION COST $15,000,000 Bombardier Aerospace year production run. Canadair, later acquired by Bombardier Aerospace, originated in 1911 as a subsidiary In 1976, General Dynamics sold Canadair to the Canadian government following a of the British shipbuilding company, Vickers, Sons and Maxim. They were initially slowdown in defense and military contracts. Canadair was eventually sold by the known as Canadian Vickers and the company was established to contract with the Canadian government to Bombardier in 1986. After acquiring Canadair, Bombardier Royal Canadian Navy to build large ships, including many that were used by the acquired the Ireland-based Short Brothers aircraft manufacturing company in 1989. Canadian and British during World War I. -

Canadian Airmen Lost in Wwii by Date 1943

CANADA'S AIR WAR 1945 updated 21/04/08 January 1945 424 Sqn. and 433 Sqn. begin to re-equip with Lancaster B.I & B.III aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). 443 Sqn. begins to re-equip with Spitfire XIV and XIVe aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). Helicopter Training School established in England on Sikorsky Hoverfly I helicopters. One of these aircraft is transferred to the RCAF. An additional 16 PLUTO fuel pipelines are laid under the English Channel to points in France (Oxford). Japanese airstrip at Sandakan, Borneo, is put out of action by Allied bombing. Built with forced labour by some 3,600 Indonesian civilians and 2,400 Australian and British PoWs captured at Singapore (of which only some 1,900 were still alive at this time). It is decided to abandon the airfield. Between January and March the prisoners are force marched in groups to a new location 160 miles away, but most cannot complete the journey due to disease and malnutrition, and are killed by their guards. Only 6 Australian servicemen are found alive from this group at the end of the war, having escaped from the column, and only 3 of these survived to testify against their guards. All the remaining enlisted RAF prisoners of 205 Sqn., captured at Singapore and Indonesia, died in these death marches (Jardine, wikipedia). On the Russian front Soviet and Allied air forces (French, Czechoslovakian, Polish, etc, units flying under Soviet command) on their front with Germany total over 16,000 fighters, bombers, dive bombers and ground attack aircraft (Passingham & Klepacki). During January #2 Flying Instructor School, Pearce, Alberta, closes (http://www.bombercrew.com/BCATP.htm). -

Midwest Association of Rail Shippers

MIDWEST ASSOCIATION OF RAIL SHIPPERS FINAL LIST OF 469 REGISTRATIONS FOR THE JULY 2018 MARS MEETING SORTED ALPHABETICALLY BY REGISTRANT LAST NAME Last First Title Company City State Chicago Freight Car Leasing Abraham Larry Director, Fleet Operations Co. Schaumburg IL Assistant Vice President Adcock Frank Marketing TTX Company Chicago IL Regional Sales Manager - Albert Greg Midwest Alta Max, LLC Geneva IL Albin Kirk United Suppliers, Inc. Aliota Robert Dir. Chemical Transportation Trelleborg Sealing Solutions Charlotte NC VP Sales & Grp. Mgr. Auto & Allen Marc Intermodal The Greenbrier Companies Southlake TX Almajed Khaled Beverly Hills CA Amick Dennis President Railcar Leasing Specialists Wilmette IL Amick Debra Railcar Leasing Specialists Anderson Jeffrey Vice President Sales Wells Fargo Rail Chicago IL Anderson Martha Executive Director James Street Associates Blue Island IL Anderson David Account Manger CN Geneva IL Appel Peter Vice President ITE Management Chicago IL Aseltine Richard Regional Sales Director RailComm, LLC - Fairport, NY Fairport NY Babcock Robert SVP-Operations and Bus. Dev. Indiana Rail Road Company Indianapolis IN Bahnline Kevin Director Rail Marketing RESDICO Chicago IL Chicago Freight Car Leasing Baker Scott Sales Director Co. Schaumburg IL Bal Gagan Marketing Specialist Trelleborg Sealing Solutions Schaumburg IL Banker Steven Logistics Development Manager Badger Mining Corporation Pulaski WI Bannerman Jayme Trackmobile Specialist Voss Equipment, Inc. Harvey IL Barenfanger Charles President Effingham Railroad -

Our Canadian Aerospace Industry: Towards a Second Century of History-Making

Our Canadian Aerospace Industry: Towards a Second Century of History-making Presentation by Robert E. Brown President and Chief Executive Officer CAE Inc. Before the AIAC 47th Annual General Meeting and Conference Wednesday, September 17, 2008 Page 1 Good morning, Ladies and Gentlemen. It is a pleasure for me to be here today and acknowledge the presence of so many friends and business partners. Next year, Canada will mark the 100th anniversary of the first airplane flight over our land. In February 1909, a pioneer by the name of J.A.D. McCurdy took to the sky in a frail-looking biplane called the Silver Dart. Young McCurdy and Canada’s tiny aviation community never looked back, and as a result, their daring achievement led to the development of a whole new industry — our own aerospace industry. How did a country with a population of 7 million in the early 20th century become the fourth nation in the world in the field of aerospace? How did Montreal become the only place in the world where you can build an entire aircraft? How did we manage to attract, develop and hang on to global leaders like Bell Helicopter Textron, Pratt & Whitney Canada and Bombardier? And, closer to my own heart, how did an enterprise like CAE become a world leader in civil simulation, with more than 70% of the market? How can a country as small as Canada, have such a glorious jewel in its crown? To find the answers to these questions, one must go back in time. Shortly after McCurdy’s groundbreaking flight, World War 1 saw Canada’s aviation industry take off. -

The Bonusing of Factories at the Lakehead, 1885-1914 Thorold J

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 14:50 Urban History Review Revue d'histoire urbaine Buying Prosperity The Bonusing of Factories at the Lakehead, 1885-1914 Thorold J. Tronrud Trends and Questions in New Historical Accounts of Policing Résumé de l'article Volume 19, numéro 1, june 1990 Durant les trois décennies précédant 1914, sans négliger aucun moyen susceptible d’attirer l’industrie, Fort William et Fort Arthur (aujourd’hui URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1017574ar rebaptisée Thunder Bay) mirent fortement l’accent sur les subventions. DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1017574ar Ensemble elles versent ainsi aux entreprises des sommes qui sans doute ne trouvaient d’équivalent dans aucune ville canadienne. Ce faisant elles Aller au sommaire du numéro alimentèrent la controverse parmi leurs contribuables sur l’utilité et l’à-propos de ce genre de mesure. Les auteurs analysent l’ampleur et les effets des subventions qu’elles consentirent et les débats qui s’ensuivirent. Il appert que si de tels incitatifs pouvaient bel et bien, à court terme, stimuler la croissance Éditeur(s) industrielle, par la suite, la survie des entreprises reposait sur le dynamisme Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine économique du milieu et sur les conditions géographiques. ISSN 0703-0428 (imprimé) 1918-5138 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Tronrud, T. J. (1990). Buying Prosperity: The Bonusing of Factories at the Lakehead, 1885-1914. Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine, 19(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.7202/1017574ar All Rights Reserved © Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine, 1990 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

Canada's Privatization of Military Ammunition Production

CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS This PDF document was made available CIVIL JUSTICE from www.rand.org as a public service of EDUCATION the RAND Corporation. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE Jump down to document6 INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS POPULATION AND AGING The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit PUBLIC SAFETY research organization providing SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY SUBSTANCE ABUSE objective analysis and effective TERRORISM AND solutions that address the challenges HOMELAND SECURITY facing the public and private sectors TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE around the world. U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Lessons from the North Canada’s Privatization of Military Ammunition Production W. MICHAEL HIX BRUCE HELD ELLEN M. PINT Prepared for the Office of the Secretary of Defense Approved for public release, distribution unlimited The research described in this report was sponsored by the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD). -

(RE 13728) an RFC Recruit's Reaction to Spinning Is Tested in a Re

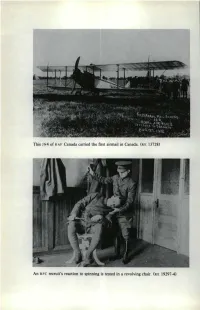

This J N4 of RAF Canada carried the first ainnail in Canada. (R E 13728) An RFC recruit's reaction to spinning is tested in a revolving chair. (RE 19297-4) Artillery co-operation instruction RFC Canada scheme. The diagrams on the blackboard illustrate techniQues of rang.ing. (RE 64-507) Brig.-Gen. Cuthbert Hoare (centre) with his Air Staff. On the right is Lt-Col. A.K. Tylee of Lennox ville, Que., responsible for general supervision of training. Tylee was briefly acting commander of RAF Canada in 1919 before being appointed Air Officer Commanding the short-lived postwar CAF in 1920. (RE 64-524) Instruction in the intricacies of the magneto and engine ignition was given on wingless (and sometimes tailless) machines known as 'penguins.' (AH 518) An RFC Canada barrack room (RE 19061-3) Camp Borden was the first of the flying training wings to become fully organized. Hangars from those days still stand, at least one of them being designated a 'heritage building.' (RE 19070-13) JN4 trainers of RFC Canada, at one of the Texas fields in the winter of I 917-18 (R E 20607-3) 'Not a good landing!' A JN4 entangled in Oshawa's telephone system, 22 April 1918 (RE 64-3217) Members of HQ staff, RAF Canada, at the University of Toronto, which housed the School of Military Aeronautics. (RE 64-523) RFC cadets on their way from Toronto to Texas in October 1917. Canadian winters, it was believed, would prevent or drastically reduce flying training. (RE 20947) JN4s on skis devised by Canadian Aeroplanes Ltd, probably in February 1918. -

British Aircraft in Russia Bombers and Boats

SPRING 2004 - Volume 51, Number 1 British Aircraft in Russia Viktor Kulikov 4 Bombers and Boats: SB-17 and SB-29 Combat Operations in Korea Forrest L. Marion 16 Were There Strategic Oil Targets in Japan in 1945? Emanuel Horowitz 26 General Bernard A. Schriever: Technological Visionary Jacob Neufeld 36 Touch and Go in Uniforms of the Past JackWaid 44 Book Reviews 48 Fleet Operations in a Mobile War: September 1950 – June 1951 by Joseph H. Alexander Reviewed by William A. Nardo 48 B–24 Liberator by Martin Bowman Reviewed by John S. Chilstrom 48 Bombers over Berlin: The RAF Offensive, November 1943-March 1944 by Alan W. Cooper Reviewed by John S. Chilstrom 48 The Politics of Coercion: Toward A Theory of Coercive Airpower for Post-Cold War Conflict by Lt. Col. Ellwood P. “Skip” Hinman IV Reviewed by William A. Nardo 49 Ending the Vietnam War: A History of America’s Involvement and Extrication from the Vietnam War by Henry Kissinger Reviewed by Lawrence R. Benson 50 The Dynamics of Military Revolution, 1300-2050 by MacGregor Knox and Williamson Murray, eds. Reviewed by James R. FitzSimonds 50 To Reach the High Frontier: A History of U.S. Launch Vehicles by Roger D. Launius and Dennis R. Jenkins, eds. Reviewed by David F. Crosby 51 History of Rocketry and Astronautics: Proceedings of the Thirtieth History Symposium of the International Academy of Astronautics, Beijing, China, 1996 by Hervé Moulin and Donald C. Elder, eds. Reviewed by Rick W. Sturdevant 52 Secret Empire: Eisenhower, the CIA, and the Hidden Story of America’s Space Espionage by Philip Taubman Reviewed by Lawrence R. -

ENGINEERING HISTORY PAPER #92 “150 Years of Canadian Engineering: Timelines for Events and Achievements”

THE ENGINEERING INSTITUTE OF CANADA and its member societies L'Institut canadien des ingénieurs et ses sociétés membres EIC’s Historical Notes and Papers Collection (Compilation of historical articles, notes and papers previously published as Articles, Cedargrove Series, Working Papers or Journals) ENGINEERING HISTORY PAPER #92 “150 Years of Canadian Engineering: Timelines for Events and Achievements” by Andrew H. Wilson (previously produced as Cedargrove Series #52/2019 – May 2019) *********************** EIC HISTORY AND ARCHIVES *********************** © EIC 2019 PO Box 40140, Ottawa ON K1V 0W8 +1 (613) 400-1786 / [email protected] / http://www.eic-ici.ca THE CEDARGROVE SERIES OF DISCOURSES, MEMOIRS AND ESSAYS #52/2019 150 YEARS OF CANADIAN ENGINEERING: TIMELINES FOR EVENTS AND ACHIEVEMENTS by Andrew H. Wilson May 2019 Abstract The research for this paper was done as part of a sesquicentennial project on 150 Years of Canadian Engineering. Some of its material has also been presented orally. This paper covers briefly and selectively Canadian engineering events and achievements in four time periods: one up to the time of Confederation in 1867, and three others between then and 2017. Associated with the three later periods are corresponding economic/political/social timelines to help put the engineering in context. There are no comments in it on the quality of the design, construction/manufacture, origins and uses of the items listed. This paper took a whole lot longer than expected to research and write, so that it carries a date in 2019 rather than late in 2017, when the chronological material in it ends. There are no maps or photographs. -

William Faulknerâ•Žs Flight Training in Canada

Studies in English Volume 6 Article 8 1965 William Faulkner’s Flight Training in Canada A. Wigfall Green University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_studies_eng Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Green, A. Wigfall (1965) "William Faulkner’s Flight Training in Canada," Studies in English: Vol. 6 , Article 8. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_studies_eng/vol6/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in English by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Green: William Faulkner’s Flight Training in Canada WILLIAM FAULKNER'S FLIGHT TRAINING IN CANADA by A. Wigfall Green “I created a cosmos of my own,” William Faulkner said to Jean Stein in New York in midwinter just after 1956 had emerged. “I like to think of the world I created as being a kind of key stone in the Universe.” He was speaking, obviously, of the small world of his fiction which reflected in miniature the great world of fact. “The reason I don’t like interviews,” he said, turning from his novels to himself, “is that I seem to react violently to personal questions. If the questions are about the work, I try to answer diem. When they are about me, I may answer or I may not, but even if I do, if the same question is asked tomorrow, the answer may be different.”1 And he might have said more: that he as mythmaker enjoyed deluding the public concerning his entire background. -

Celebrating the Centennial of Naval Aviation in 1/72 Scale

Celebrating the Centennial of Naval Aviation in 1/72 Scale 2010 USN/USMC/USCG 1/72 Aircraft Kit Survey J. Michael McMurtrey IPMS-USA 1746 Carrollton, TX [email protected] As 2011 marks the centennial of U.S. naval aviation, aircraft modelers might be interested in this list of US naval aircraft — including those of the Marines and Coast Guard, as well as captured enemy aircraft tested by the US Navy — which are available as 1/72 scale kits. Why 1/72? There are far more kits of naval aircraft available in this scale than any other. Plus, it’s my favorite, in spite of advancing age and weakening eyes. This is an updated version of an article I prepared for the 75th Anniversary of US naval aviation and which was published in a 1986 issue of the old IPMS-USA Update. It’s amazing to compare the two and realize what developments have occurred, both in naval aeronautical technology and the scale modeling hobby, but especially the latter. My 1986 list included 168 specific aircraft types available in kit form from thirty- three manufacturers — some injected, some vacuum-formed — and only three conversion kits and no resin kits. Many of these names (Classic Plane, Contrails, Eagle’s Talon, Esci, Ertl, Formaplane, Frog, Griffin, Hawk, Matchbox, Monogram, Rareplane, Veeday, Victor 66) are no longer with us or have been absorbed by others. This update lists 345 aircraft types (including the original 168) from 192 different companies (including the original 33), many of which, especially the producers of resin kits, were not in existence in 1986, and some of which were unknown to me at the time.