Wines of Greece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abai, Oracle of Apollo, 134 Achaia, 3Map; LH IIIC

INDEX Abai, oracle of Apollo, 134 Aghios Kosmas, 140 Achaia, 3map; LH IIIC pottery, 148; migration Aghios Minas (Drosia), 201 to northeast Aegean from, 188; nonpalatial Aghios Nikolaos (Vathy), 201 modes of political organization, 64n1, 112, Aghios Vasileios (Laconia), 3map, 9, 73n9, 243 120, 144; relations with Corinthian Gulf, 127; Agnanti, 158 “warrior burials”, 141. 144, 148, 188. See also agriculture, 18, 60, 207; access to resources, Ahhiyawa 61, 86, 88, 90, 101, 228; advent of iron Achaians, 110, 243 ploughshare, 171; Boeotia, 45–46; centralized Acharnai (Menidi), 55map, 66, 68map, 77map, consumption, 135; centralized production, 97–98, 104map, 238 73, 100, 113, 136; diffusion of, 245; East Lokris, Achinos, 197map, 203 49–50; Euboea, 52, 54, 209map; house-hold administration: absence of, 73, 141; as part of and community-based, 21, 135–36; intensified statehood, 66, 69, 71; center, 82; centralized, production, 70–71; large-scale (project), 121, 134, 238; complex offices for, 234; foreign, 64, 135; Lelantine Plain, 85, 207, 208–10; 107; Linear A, 9; Linear B, 9, 75–78, 84, nearest-neighbor analysis, 57; networks 94, 117–18; palatial, 27, 65, 69, 73–74, 105, of production, 101, 121; palatial control, 114; political, 63–64, 234–35; religious, 217; 10, 65, 69–70, 75, 81–83, 97, 207; Phokis, systems, 110, 113, 240; writing as technology 47; prehistoric Iron Age, 204–5, 242; for, 216–17 redistribution of products, 81, 101–2, 113, 135; Aegina, 9, 55map, 67, 99–100, 179, 219map subsistence, 73, 128, 190, 239; Thessaly 51, 70, Aeolians, 180, 187, 188 94–95; Thriasian Plain, 98 “age of heroes”, 151, 187, 200, 213, 222, 243, 260 agropastoral societies, 21, 26, 60, 84, 170 aggrandizement: competitive, 134; of the sea, 129; Ahhiyawa, 108–11 self-, 65, 66, 105, 147, 251 Aigai, 82 Aghia Elousa, 201 Aigaleo, Mt., 54, 55map, 96 Aghia Irini (Kea), 139map, 156, 197map, 199 Aigeira, 3map, 141 Aghia Marina Pyrgos, 77map, 81, 247 Akkadian, 105, 109, 255 Aghios Ilias, 85. -

Artemis Karamolegos Wines Descriptions for Wine Experts

ARTEMIS KARAMOLEGOS WINES DESCRIPTIONS FOR WINE EXPERTS Having its roots in the volcanic soil of Santorini and tradition that goes back to 1952, the winery of Artemis Karamolegos is one of the most dynamic and rapidly evolving wineries of Santorini. All its wines have been distinguished in several important International Wine Competitions. The winery has the most modern facilities for wine production, spaces for wine testing and a shop for wines and selected local products. Artemis Karamolegos had the innovative idea to combine the experience of a tour at the winery with lunch at the restaurant Aroma Avlis, the menu of which has the signature of the talented chef Christos Coskinas. In its spacious new yard offering view to the vineyard and the beaches of Monolithos and Avis, as well as in the dinning halls, you can taste the delicious Mediterranean and local dishes made with fresh, carefully selected local products, accompanied with wines from the winery. The history of the winery goes back to the 1952, where the grandfather, Artemis, was cultivating the vineyards in order to produce wine for his own family and later on, in order to sell it in the island and in the rest of Greece. Artemis Karamolegos, the grandson who succeeded his grandfather and his father at the winery of Exo Gonia, is an energetic young man full of passion for his Job. Since 2004 and until today, he managed to lead, miraculously, the family business many steps ahead very fast. In 2004, a turn to a modern and of a high quality production winery took place, with the production of a bottled, labeled and of a good quality wine named “SANTORINI”. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Sparkling & Champagne ............................. 3 White Wine .................................................. 4 Greece ........................................................................................4 Mediterranean ..................................................................... 6 Germany .................................................................................. 6 Italy ............................................................................................... 6 Spain ........................................................................................... 6 France ........................................................................................ 6 From the New World .......................................................7 Rosé Wine ................................................ 8 Skin-Contact Wine ................................... 9 Red Wine .................................................10 Greece .............................................................................10 Mediterranean ...........................................................13 Italy ..................................................................................... 13 Spain .................................................................................. 13 France................................................................................14 From the New World ............................................ 14 Thrace Macedonia Epirius Thessaly Ionian Islands Aegean Peloponnese Islands Crete 2 SPARKLING -

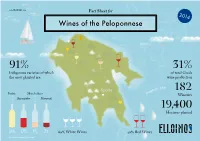

Wine Map of the Peleponnese 2014

www.ELLOINOS.com Fact Sheet for 2014 Wines of the Peloponnese Patras Athens 91% 31% Indigenous varieties of which of total Greek the most planted are: wine production n Sea Sparta gea 182 Ae Roditis Moschofilero Wineries Agiorgitiko Mavroudi 19,400 Hectares planted 34% 17% 9% 7% 60% White Wines 40% Red Wines Information design by ideologio Protected Designation of Origin Wine Colors Muscat of Rio Patras Grape: Muscat Blanc Mavrodaphne of Patras Grapes: Mavrodaphne, Korinthiaki Athens Nemea Grape Agiorgitiko Muscat of Patras Mantinia Grape: Muscat Blanc Grape Moschofilero Patras Epidaurus Grape: Roditis Sea ean eg Kalamata A In the EU, schemes of geographical indications known as Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) and Protected Monemvassia Geographical Indication (PGI), promote and protect names of —Malvasia quality agricultural and food products. Amongst many other products, the names of wines are also protected by these Grapes: Monemvassia (min 51%), laws. Assyrtiko, Asproudes, Kydonitsa PDO products are prepared, processed, and produced in a given geographical area, using recognized know-how and therefore acquire unique properties. White Wine Sweet White Wine Red Wine Sweet Red Wine Indigenous grapes International grapes Region Note There are additional grape varieties allowed, but PGI products are closely linked to the geographical current plantings are small. area in which they are traditionally and at least White indigenous: Asproudes Patras, Aidani, partially manufactured (prepared, processed OR Assyrtiko, Athiri, Glikerithra, Goustolidi, Laghorthi, produced), and have specific qualities attributable to Migdali, Petroulianos, Potamissi, Robola, Rokaniaris, Skiadopoulo, Sklava, Volitsa Aspro. that geographical area, therefore acquiring unique properties. Depending on their geographical breadth, Red indigenous: Limniona, Skylopnichtis, Thrapsa, Voidomatis, Volitsa. -

Annual Environmental Management Report

Annual Environmental Management Report Reporting Period: 1/1/2018÷ 31/12/2018 Submitted to EYPE/Ministry of the Environment, Planning and Public Works within the framework of the JMDs regarding the Approval of the Environmental Terms of the Project & to the Greek State in accordance with Article 17.5 of the Concession Agreement Aegean Motorway S.A. – Annual Environmental Management Report – January 2019 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 3 2. The Company ............................................................................................................... 3 3. Scope .......................................................................................................................... 4 4. Facilities ....................................................................................................................... 8 5. Organization of the Concessionaire .............................................................................. 10 6. Integrated Management System .................................................................................. 11 7. Environmental matters 2018 ....................................................................................... 13 8. 2018 Public Relations & Corporate Social Responsibility Activity ..................................... 32 Appendix 1 ........................................................................................................................ 35 MANAGEMENT -

The Wine List

The Wine List Here at Balzem we have taken extra time to design a wine program that celebrates the artisans, farmers and passionate winemakers who have chosen to make a little bit of wine that is unique, hand-made, true to its terroir and delicious rather than making giant amounts of wine that all tastes the same to please the masses. Champagne, Sparkling and Rosé Wines. page 1 ~~~~~~ Light & Crisp White Wines. page 2 Medium Bodied & Smooth White Wines. page 3 Full Bodied & Rich White Wines. page 4 ~~~~~~ Light & Aromatic Red Wines. page 5 Medium Bodied & Smooth Red Wines. .page 6 Full Bodied & Rich Red Wines. page 7 and 8 ~~~~~~ Seasonal Selections. page 9 California Beauties, Dessert Wines . page 10 and 11 Cocktails & Beer. page 12 Champagne & Sparkling Wines #02. Saumur Rosé N.V. Louis de Grenelle, Loire ValleY – FR 17/glass; 67/bottle #03. Prosecco 2019 Scarpetta, Friuli – IT 57/bottle #04. Pinot Meunier, Champagne, Brut N.V. Jose Michel, Champagne – FR 89/bottle Rosé Wine #06. Côtes de Provence, Quinn Rosé 2019 Provence – FR 17/glass; 57/bottle #07. Côtes de Provence, Domaine Jacourette 2016 Magnum (1,5L) Provence – FR 73/Magnum 1 Light & Crisp White Wines On this page you will find wines that are fresh, dry and bright they typically pair well with warm days, seafood or the sipper who prefers dry, crisp, bright wines. The smells and flavors are a range of citrus notes and wild flowers. Try these if you like Sauvignon Blanc or Pinot Grigio #08. Verdejo, Bodegas Menade 2019 (Sustainable) Rueda – SP 13/glass #09. -

Effect of Pruning Severity on Vegetative, Physiological, Yield and Quality Attributes in Grape (Vitis Vinifera L.): a Review

Current Agriculture Research Journal Vol. 3(1), 42-54 (2015) Effect of Pruning Severity on Vegetative, Physiological, Yield and Quality Attributes in Grape (Vitis vinifera L.): A Review S. SENTHILKUMAR1*, R.M. VIJayaKUMAR2, K. SOORIANATHASUNDARAM2 and D. DURGA DEVI2 1RVS Padmavathy College of Horticulture, Sempatti (Dindigul Dist.), Tamil Nadu - 624 707, India. 2Department of Fruit Crops, TNAU, Coimbatore, India. http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CARJ.3.1.06 (Received: March 11, 2015; Accepted: May 2, 2015) ABSTRACT Grape is one among the most delicious, refreshing and nourishing fruits of the world. It is one of the earliest fruits grown by man. The berries are a good source of sugars and minerals like Ca, Mg, Fe, and vitamins like B1, B2, and C. Grape has so many uses and is so unique that no fruit can challenge their superiority. Crop load is the most important factor affecting yield and cluster quality as well as vine vigor of both seeded and seedless varieties. Hence, an optimum canopy size and bunch number per vine are to be maintained for achieving better fruit Quality which warrants proper balancing between vigour and capacity. The pruning requirement of different varieties differs as per their growth behaviour. Therefore, variety-specific standardization of pruning is essential for any grape cultivars for harnessing potential yield and quality. In this view, it is essential to get scientific information on the pruning requirement of grapes. Pruning all the matured canes to fruit bud level, as adopted by local grape growers results in more exploitation of reserved food material leading to loss of vigour, quality and early setting of senility in vines. -

Determining the Classification of Vine Varieties Has Become Difficult to Understand Because of the Large Whereas Article 31

31 . 12 . 81 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 381 / 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION ( EEC) No 3800/81 of 16 December 1981 determining the classification of vine varieties THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Whereas Commission Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/ 70 ( 4), as last amended by Regulation ( EEC) No 591 /80 ( 5), sets out the classification of vine varieties ; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Whereas the classification of vine varieties should be substantially altered for a large number of administrative units, on the basis of experience and of studies concerning suitability for cultivation; . Having regard to Council Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 of 5 February 1979 on the common organization of the Whereas the provisions of Regulation ( EEC) market in wine C1), as last amended by Regulation No 2005/70 have been amended several times since its ( EEC) No 3577/81 ( 2), and in particular Article 31 ( 4) thereof, adoption ; whereas the wording of the said Regulation has become difficult to understand because of the large number of amendments ; whereas account must be taken of the consolidation of Regulations ( EEC) No Whereas Article 31 of Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 816/70 ( 6) and ( EEC) No 1388/70 ( 7) in Regulations provides for the classification of vine varieties approved ( EEC) No 337/79 and ( EEC) No 347/79 ; whereas, in for cultivation in the Community ; whereas those vine view of this situation, Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/70 varieties -

Wine List Lauda 2019

WINE LIST 2019 INDEX OF CONTENTS WHITE CHAMPAGNES 03 ROSE CHAMPAGNES 04 WHITE SPARKLING WINES 05 ROSE & SPARKLING WINES 06 WHITE WINES 07 GREECE 07 ITALY 13 FRANCE 16 SPAIN, AUSTRIA & GERMANY 19 HUNGURY, GEORGIAN REPUBLIC, LEBANON, AMERICA 20 AUSTRALIA 21 NEW ZEALAND 22 ROSE WINES 23 GREECE 23 ITALY, FRANCE, SPAIN, LEBANON, ARGENTINA, NEW ZEALAND 24 RED WINES 25 GREECE 25 ITALY 30 FRANCE 33 SPAIN, PORTUGAL 38 AUSTRIA, LEBANON, SOUTH AFRICA, AMERICA 39 AUSTRALIA, NEW ZEALAND 41 DESSERT WINES 42 GREECE 42 REST OF THE WORLD 43 FORTIFIED WINES 44 EAU DE VIE 44 BRANDY 44 LIQUEUR 44 CHAMPAGNES WHITE CHAMPAGNES WHITE CHAMPAGNES Grand Siecle Brut NV, Laurent Perrier, Tours-sur-Marne Brut Millesime 2008, Palmer & Co, Reims chardonnay pinot noir chardonnay, pinot noir, pinot meunier 640 252 Champ Cain 2005, Jacquesson, Avize Blanc de Noirs NV, Palmer & Co, Reims pinot noir, pinot meunier, chardonnay pinot noir, pinot meunier 593 263 Blanc de Blancs NV, Billecart-Salmon, Ay Grande Cuvee NV, Krug, Reims chardonnay chardonnay, pinot noir , pinot meunier 306 669 Fut de Chene Grand Cru NV, Henri Giraud, Ay La Grande Dame 2006, Veuve Cliquot, Reims pinot noir, chardonnay chardonnay, pinot noir 588 561 Code Noir NV, Henri Giraud, Ay Comtes de Champagne Blanc de Blancs 2007, Taittinger, Reims pinot noir chardonnay 448 514 R.D. Extra Brut 2002, Bollinger, Ay Cristal 2009, Louis Roederer, Reims pinot noir, chardonnay pinot noir , chardonnay 872 697 Brut Reserve NV, Charles Heidsieck, Reims Rare 2002, Piper Heidsieck, Reims chardonnay, pinot noir, pinot meunier -

Commission Implementing Decision of 31 January 2019 on The

7.2.2019 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 49/3 COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING DECISION of 31 January 2019 on the publication in the Official Journal of the European Union of an application for amendment of a specification for a name in the wine sector referred to in Article 105 of Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council (Πλαγιές Πάικου (Playies Paikou) (PGI)) (2019/C 49/04) THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 establishing a common organisation of the markets in agricultural products and repealing Council Regulations (EEC) No 922/72, (EEC) No 234/79, (EC) No 1037/2001 and (EC) No 1234/2007 (1), and in particular Article 97(3) thereof, Whereas: (1) Greece has sent an application for amendment of the specification for the name ‘Πλαγιές Πάικου’ (Playies Paikou) in accordance with Article 105 of Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013. (2) The Commission has examined the application and concluded that the conditions laid down in Articles 93 to 96, Article 97(1), and Articles 100, 101 and 102 of Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 have been met. (3) In order to allow for the presentation of statements of opposition in accordance with Article 98 of Regulation (EU) No 1308 /2013, the application for amendment of the specification for the name ‘Πλαγιές Πάικου’ (Playies Paikou) should be published in the Official Journal of the European Union, HAS DECIDED AS FOLLOWS: Sole Article The application for amendment of the specification for the name ‘Πλαγιές Πάικου’ (Playies Paikou) (PGI) in accordance with Article 105 of Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013, is contained in the Annex to this Decision. -

Bulgaria Country Profile

Bulgaria Country Profile August 2019 A publication BACKGROUND The Bulgars, a Central Asian Turkic tribe, merged with the local Slavic inhabitants in the late 7th century to form the first Bulgarian state. In succeeding centuries, Bulgaria struggled with the Byzantine Empire to assert its place in the Balkans, but by the end of the 14th century the country was overrun by the Ottoman Turks. Northern Bulgaria attained autonomy in 1878 and all of Bulgaria became independent from the Ottoman Empire in 1908. Having fought on the losing side in both World Wars, Bulgaria fell within the Soviet sphere of influence and became a People’s Republic in 1946. Communist domination ended in 1990, when Bulgaria held its first multiparty election since World War II and began the contentious process of moving toward political democracy and a market economy while combating inflation, unemployment, corruption, and crime. The country joined NATO in 2004 and the EU in 2007. Geography: Southeastern Europe, bordering the Black Sea, between Romania and Turkey. Total area 110,879 sq km. People: Total population is 7,101,510 and median age is 42.7 years. Agriculture: Vegetables, fruits, tobacco, wine, wheat, barley, sunflowers, sugar beets; livestock. Industries: Electricity, gas, water; food, beverages, tobacco; machinery and equipment, automotive parts, base metals, chemical products, coke, refined petroleum, nuclear fuel; outsourcing centers. Environment: Air pollution from industrial emissions; rivers polluted from raw sewage, heavy metals, detergents; deforestation; forest damage from air pollution and resulting acid rain; soil contamination from heavy metals from metallurgical plants and industrial wastes. Economy and Infrastructure: Bulgaria, a former communist country that entered the EU in 2007, has an open economy that historically has demonstrated strong growth, but its per-capita income remains the lowest among EU members and its reliance on energy imports and foreign demand for its exports makes its growth sensitive to external market conditions. -

Winelist Fall 19.Pdf

u WINES BY THE GLASS u ποτήρι κρασί Retsina glass bottle 17 Kechris, ‘Tear of the Pine’ Retsina, Thessaloniki 14 56 18 Kechris, ‘Kechribari’ Retsina, Thessaloniki, 500ml 12 Sparkling 12 Glinavos ‘Zitsa Brut,’ Zitsa, Epirus 16 64 17 Kir-Yianni Rosé ‘Akakies,’ Amyndaio 13 52 Wh i t e 17 Moschofilero, Troupis ‘Fteri,’ Arkadia 11 44 18 Assyrtiko, Gai’a ‘Thalassitis,’ Santorini 16 64 17 Malvasia, Douloufakis ‘Femina,’ Crete 13 52 17 Assyrtiko / Malagouzia, Domaine Nerantzi 16 64 ‘Pentapolis,’ Serres, Macedonia Orange 18 Sauvignon Blanc, Oenogenisis ‘Mataroa,’ Drama 14 56 Rosé 17 Sideritis, Ktima Parparoussis ‘Petit Fleur,’ Achaia, Peloponnese 13 52 Red 17 Xinomavro, Thymiopoulos ‘Young Vines,’ Naoussa 13 52 17 Mavrodaphne, Sklavos ‘Orgion,’ Kefalonia 16 64 16 Agiorgitiko, Tselepos, Nemea, Peloponnese 13 52 16 Limniona, Domaine Zafeirakis, Tyrnavos, Thessaly 16 64 16 Tsapournakos, Voyatzi, Velvento, Macedonia 16 64 Carafe white/red καράφα Please ask your server! 32 u u u u u u WINES BY THE BOTtLE SPARKLING αφρώδες κρασί orange πορτοκαλί κρασί 17 Domaine Spiropoulos ‘Ode Panos’ Brut, Mantinia, Peloponnese 58 17 Roditis / Moschatela / Vostylidi / Muscat, Sclavos ‘Alchymiste,’ Kefalonia 38 Stone fruits and fl owers. Nectar of the gods. Dip your toes in the orange wine pool with this staff fave. Aromatic and affable. 13 Tselepos ‘Amalia’ Brut, Nemea, Peloponnese 90 18 Savatiano, Georgas Family, Spata 48 Rustic and earthy, from the hottest, driest region in Greece. Sort of miracle wine. Better than Veuve. (For real, though.) NV Tselepos ‘Amalia’ Brut Roze, Nemea, Peloponnese 60 NV Aspro Potamisi / Rosaki, Kathalas ‘Un Été Grec’, Tinos 120 The new cult classic.