Sinification of Zhuang Place Names in Guangxi, China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stochastic Model of Stroke Order Variation

2009 10th International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition Stochastic Model of Stroke Order Variation Yoshinori Katayama, Seiichi Uchida, and Hiroaki Sakoe Faculty of Information Science and Electrical Engineering, Kyushu University, 819-0395, Japan fyosinori,[email protected] Abstract “ ¡ ” under an unnatural stroke correspondence which max- imizes their similarity. Note that the correct stroke order of A stochastic model of stroke order variation is proposed “ ” is (“—” ! “j' ! “=” ! “n” ! “–”) and that of “ ¡ ” and applied to the stroke-order free on-line Kanji character is (“—” ! “–” ! “j' ! “=” ! “n” ). Thus if we allow any recognition. The proposed model is a hidden Markov model stroke order variation, those two characters become almost (HMM) with a special topology to represent all stroke order identical. variations. A sequence of state transitions from the initial One possible remedy to suppress the misrecognitions is state to the final state of the model represents one stroke to penalize unnatural i.e., rare stroke order on optimizing order and provides a probability of the stroke order. The the stroke correspondence. In fact, there are popular stroke distribution of the stroke order probability can be trained orders (including the standard stroke order) and there are automatically by using an EM algorithm from a training rare stroke orders. If we penalize the situation that “ ¡ ” is set of on-line character patterns. Experimental results on matched to an input pattern with its very rare stroke order large-scale test patterns showed that the proposed model of (“—” ! “j' ! “=” ! “n” ! “–”), we can avoid the could represent actual stroke order variations appropriately misrecognition of “ ” as “ ¡ .” and improve recognition accuracy by penalizing incorrect For this purpose, a stochastic model of stroke order vari- stroke orders. -

Nushu and the Writing of Religious

NOSHU AND RELIGIOUS CULTURE IN CHINA "MY MOTHER WATCHED OVER AN EMPTY HOUSE AND',WAS SEPARATED FROM THE HEA VENL Y FEMALE": NUSHU AND THE WRITING OF RELIGIOUS CULTURE IN CHINA By STEPHANIE BALK WILL, B.A. (H.Hons.) A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial FulfiHment ofthe Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Stephanie Balkwill, August 2006 MASTER OF ARTS (2006) McMaster University (Religious Studies) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: "My Mother Watched Over an Empty House and was Separated From the Heavenly Female": Nushu and the Writing IOf Religious Culture in China. AUTHOR: Stephanie Balkwill, B.A. (H.Hons.) (University of Regina) SUPERVISOR: Dr. James Benn NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 120 ii ]rll[.' ' ABSTRACT Niishu, or "Women's Script" is a system of writing indigenous to a small group of village women in iJiangyong County, Hunan Province, China. Used exclusively by and for these women, the script was developed in order to write down their oral traditions that may have included songs, prayers, stories and biographies. However, since being discovered by Chinese and Western researchers, nushu has been rapidly brought out of this Chinese village locale. At present, the script has become an object of fascination for diverse audiences all over the world. It has been both the topic of popular media presentations and publications as well as the topic of major academic research projects published in Engli$h, German, Chinese and Japanese. Resultantly, niishu has played host to a number of mo~ern explanations and interpretations - all of which attempt to explain I the "how" and the "why" of an exclusively female script developed by supposedly illiterate women. -

Sociolinguistic Survey of Mpi in Thailand

Sociolinguistic Survey of Mpi in Thailand Ramzi W. Nahhas SIL International 2007 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2007-016, August 2007 Copyright © 2007 Ramzi W. Nahhas and SIL International All rights reserved 2 Abstract Ramzi W. Nahhas, PhD Survey Unit, Department of Linguistics School of Graduate Studies Payap University/SIL International Chiang Mai, Thailand Mpi is a language spoken mainly in only two villages in Thailand, and possibly in one location in China, as well. Currently, Mpi does not have vernacular literature, and may not have sufficient language vitality to warrant the development of such literature. Since there are only two Mpi villages in Thailand, and they are surrounded by Northern Thai communities, it is reasonable to be concerned about the vitality of the Mpi language. The purposes of this study were to assess the need for vernacular literature development among the Mpi of Northern Thailand and to determine which (if any) Mpi varieties should be developed. This assessment focused on language vitality and bilingualism in Northern Thai. Additionally, lexicostatistics were used to measure lexical similarity between Mpi varieties. Acknowledgments This research was conducted under the auspices of the Payap University Linguistics Department, Chiang Mai, Thailand. The research team consisted of the author, Jenvit Suknaphasawat (SIL International), and Noel Mann (Technical Director, Survey Unit, Payap University Linguistics Department, and SIL International). The fieldwork would not have been possible without the assistance of the residents of Ban Dong (in Phrae Province) and Ban Sakoen (in Nan Province). A number of individuals gave many hours to help the researchers learn about the Mpi people and about their village, and to introduce us to others in their village. -

The Twentieth-Century Secularization of the Sinograph in Vietnam, and Its Demotion from the Cosmological to the Aesthetic

Journal of World Literature 1 (2016) 275–293 brill.com/jwl The Twentieth-Century Secularization of the Sinograph in Vietnam, and its Demotion from the Cosmological to the Aesthetic John Duong Phan* Rutgers University [email protected] Abstract This article examines David Damrosch’s notion of “scriptworlds”—spheres of cultural and intellectual transfusion, defined by a shared script—as it pertains to early mod- ern Vietnam’s abandonment of sinographic writing in favor of a latinized alphabet. The Vietnamese case demonstrates a surprisingly rapid readjustment of deeply held attitudes concerning the nature of writing, in the wake of the alphabet’s meteoric suc- cesses. The fluidity of “language ethics” in early modern Vietnam (a society that had long since developed vernacular writing out of an earlier experience of diglossic liter- acy) suggests that the durability of a “scriptworld” depends on the nature and history of literacy in the societies under question. Keywords Vietnamese literature – Vietnamese philology – Chinese philology – script reform – language reform – early modern East Asia/Southeast Asia Introduction In 1919, the French-installed emperor Khải Định permanently dismantled Viet- nam’s civil service examinations, and with them, an entire system of political * I would like to thank Wynn Wilcox, Nguyễn Tuấn Cường, Tuna Artun, and Jack Chia for their valuable help and input. All errors are my own. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2016 | doi: 10.1163/24056480-00102010 Downloaded from Brill.com09/25/2021 07:54:41AM via free access 276 phan selection based on proficiency in Literary Sinitic.1 That same year, using a con- troversial latinized alphabet called Quốc Ngữ (lit. -

Chinese Script Generation Panel Document

Chinese Script Generation Panel Document Proposal for the Generation Panel for the Chinese Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone 1. General Information Chinese script is the logograms used in the writing of Chinese and some other Asian languages. They are called Hanzi in Chinese, Kanji in Japanese and Hanja in Korean. Since the Hanzi unification in the Qin dynasty (221-207 B.C.), the most important change in the Chinese Hanzi occurred in the middle of the 20th century when more than two thousand Simplified characters were introduced as official forms in Mainland China. As a result, the Chinese language has two writing systems: Simplified Chinese (SC) and Traditional Chinese (TC). Both systems are expressed using different subsets under the Unicode definition of the same Han script. The two writing systems use SC and TC respectively while sharing a large common “unchanged” Hanzi subset that occupies around 60% in contemporary use. The common “unchanged” Hanzi subset enables a simplified Chinese user to understand texts written in traditional Chinese with little difficulty and vice versa. The Hanzi in SC and TC have the same meaning and the same pronunciation and are typical variants. The Japanese kanji were adopted for recording the Japanese language from the 5th century AD. Chinese words borrowed into Japanese could be written with Chinese characters, while Japanese words could be written using the character for a Chinese word of similar meaning. Finally, in Japanese, all three scripts (kanji, and the hiragana and katakana syllabaries) are used as main scripts. The Chinese script spread to Korea together with Buddhism from the 2nd century BC to the 5th century AD. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Simplification of Chinese Characters in Japan and China

CONTRASTING APPROACHES TO CHINESE CHARACTER REFORM: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIMPLIFICATION OF CHINESE CHARACTERS IN JAPAN AND CHINA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2012 By Kei Imafuku Thesis Committee: Alexander Vovin, Chairperson Robert Huey Dina Rudolph Yoshimi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express deep gratitude to Alexander Vovin, Robert Huey, and Dina R. Yoshimi for their Japanese and Chinese expertise and kind encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis. Their guidance, as well as the support of the Center for Japanese Studies, School of Pacific and Asian Studies, and the East-West Center, has been invaluable. i ABSTRACT Due to the complexity and number of Chinese characters used in Chinese and Japanese, some characters were the target of simplification reforms. However, Japanese and Chinese simplifications frequently differed, resulting in the existence of multiple forms of the same character being used in different places. This study investigates the differences between the Japanese and Chinese simplifications and the effects of the simplification techniques implemented by each side. The more conservative Japanese simplifications were achieved by instating simpler historical character variants while the more radical Chinese simplifications were achieved primarily through the use of whole cursive script forms and phonetic simplification techniques. These techniques, however, have been criticized for their detrimental effects on character recognition, semantic and phonetic clarity, and consistency – issues less present with the Japanese approach. By comparing the Japanese and Chinese simplification techniques, this study seeks to determine the characteristics of more effective, less controversial Chinese character simplifications. -

The Japanese Writing Systems, Script Reforms and the Eradication of the Kanji Writing System: Native Speakers’ Views Lovisa Österman

The Japanese writing systems, script reforms and the eradication of the Kanji writing system: native speakers’ views Lovisa Österman Lund University, Centre for Languages and Literature Bachelor’s Thesis Japanese B.A. Course (JAPK11 Spring term 2018) Supervisor: Shinichiro Ishihara Abstract This study aims to deduce what Japanese native speakers think of the Japanese writing systems, and in particular what native speakers’ opinions are concerning Kanji, the logographic writing system which consists of Chinese characters. The Japanese written language has something that most languages do not; namely a total of three writing systems. First, there is the Kana writing system, which consists of the two syllabaries: Hiragana and Katakana. The two syllabaries essentially figure the same way, but are used for different purposes. Secondly, there is the Rōmaji writing system, which is Japanese written using latin letters. And finally, there is the Kanji writing system. Learning this is often at first an exhausting task, because not only must one learn the two phonematic writing systems (Hiragana and Katakana), but to be able to properly read and write in Japanese, one should also learn how to read and write a great amount of logographic signs; namely the Kanji. For example, to be able to read and understand books or newspaper without using any aiding tools such as dictionaries, one would need to have learned the 2136 Jōyō Kanji (regular-use Chinese characters). With the twentieth century’s progress in technology, comparing with twenty years ago, in this day and age one could probably theoretically get by alright without knowing how to write Kanji by hand, seeing as we are writing less and less by hand and more by technological devices. -

Glottal Stop Initials and Nasalization in Sino-Vietnamese and Southern Chinese

Glottal Stop Initials and Nasalization in Sino-Vietnamese and Southern Chinese Grainger Lanneau A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2020 Committee: Zev Handel William Boltz Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2020 Grainger Lanneau University of Washington Abstract Glottal Stop Initials and Nasalization in Sino-Vietnamese and Southern Chinese Grainger Lanneau Chair of Supervisory Committee: Professor Zev Handel Asian Languages and Literature Middle Chinese glottal stop Ying [ʔ-] initials usually develop into zero initials with rare occasions of nasalization in modern day Sinitic1 languages and Sino-Vietnamese. Scholars such as Edwin Pullyblank (1984) and Jiang Jialu (2011) have briefly mentioned this development but have not yet thoroughly investigated it. There are approximately 26 Sino-Vietnamese words2 with Ying- initials that nasalize. Scholars such as John Phan (2013: 2016) and Hilario deSousa (2016) argue that Sino-Vietnamese in part comes from a spoken interaction between Việt-Mường and Chinese speakers in Annam speaking a variety of Chinese called Annamese Middle Chinese AMC, part of a larger dialect continuum called Southwestern Middle Chinese SMC. Phan and deSousa also claim that SMC developed into dialects spoken 1 I will use the terms “Sinitic” and “Chinese” interchangeably to refer to languages and speakers of the Sinitic branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family. 2 For the sake of simplicity, I shall refer to free and bound morphemes alike as “words.” 1 in Southwestern China today (Phan, Desousa: 2016). Using data of dialects mentioned by Phan and deSousa in their hypothesis, this study investigates initial nasalization in Ying-initial words in Southwestern Chinese Languages and in the 26 Sino-Vietnamese words. -

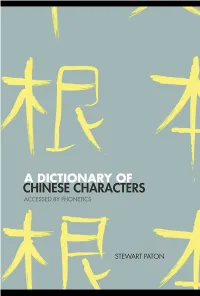

A Dictionary of Chinese Characters: Accessed by Phonetics

A dictionary of Chinese characters ‘The whole thrust of the work is that it is more helpful to learners of Chinese characters to see them in terms of sound, than in visual terms. It is a radical, provocative and constructive idea.’ Dr Valerie Pellatt, University of Newcastle. By arranging frequently used characters under the phonetic element they have in common, rather than only under their radical, the Dictionary encourages the student to link characters according to their phonetic. The system of cross refer- encing then allows the student to find easily all the characters in the Dictionary which have the same phonetic element, thus helping to fix in the memory the link between a character and its sound and meaning. More controversially, the book aims to alleviate the confusion that similar looking characters can cause by printing them alongside each other. All characters are given in both their traditional and simplified forms. Appendix A clarifies the choice of characters listed while Appendix B provides a list of the radicals with detailed comments on usage. The Dictionary has a full pinyin and radical index. This innovative resource will be an excellent study-aid for students with a basic grasp of Chinese, whether they are studying with a teacher or learning on their own. Dr Stewart Paton was Head of the Department of Languages at Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, from 1976 to 1981. A dictionary of Chinese characters Accessed by phonetics Stewart Paton First published 2008 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. -

Language Management in the People's Republic of China

LANGUAGE AND PUBLIC POLICY Language management in the People’s Republic of China Bernard Spolsky Bar-Ilan University Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, language management has been a central activity of the party and government, interrupted during the years of the Cultural Revolution. It has focused on the spread of Putonghua as a national language, the simplification of the script, and the auxiliary use of Pinyin. Associated has been a policy of modernization and ter - minological development. There have been studies of bilingualism and topolects (regional vari - eties like Cantonese and Hokkien) and some recognition and varied implementation of the needs of non -Han minority languages and dialects, including script development and modernization. As - serting the status of Chinese in a globalizing world, a major campaign of language diffusion has led to the establishment of Confucius Institutes all over the world. Within China, there have been significant efforts in foreign language education, at first stressing Russian but now covering a wide range of languages, though with a growing emphasis on English. Despite the size of the country, the complexity of its language situations, and the tension between competing goals, there has been progress with these language -management tasks. At the same time, nonlinguistic forces have shown even more substantial results. Computers are adding to the challenge of maintaining even the simplified character writing system. As even more striking evidence of the effect of poli - tics and demography on language policy, the enormous internal rural -to -urban rate of migration promises to have more influence on weakening regional and minority varieties than campaigns to spread Putonghua. -

Characteristics of Underwater Topography, Geomorphology and Sediment Source in Qinzhou Bay

water Article Characteristics of Underwater Topography, Geomorphology and Sediment Source in Qinzhou Bay Chao Cao 1,2,3,* , Feng Cai 1,2,3, Hongshuai Qi 1,2,3,4, Yongling Zheng 1 and Huiquan Lu 1 1 Third Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural and Resources, Xiamen 361005, China; [email protected] (F.C.); [email protected] (H.Q.); [email protected] (Y.Z.); [email protected] (H.L.) 2 Fujian Provincial Key Laboratory of Marine Ecological Conservation and Restoration, Xiamen 361005, China 3 Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai), Zhuhai 591000, China 4 Observation and Research Station of Coastal Wetland Ecosystem in Beibu Gulf, MNR, Beihai 536015, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-18030085312 Abstract: Human activities for exploitation and utilization of coastal zones have transformed coastline morphology and severely changed regional flow fields, underwater topography, and sediment distribution in the sea. In this study, single-beam bathymetry coupled with sediment sampling and analysis was carried out to ascertain submarine topography, geomorphology and sediment distribution patterns, and explore sediment provenance in Qinzhou Bay, China. The results show the following: (1) the underwater topography in Qinzhou Bay is complex and variable, with water depths in the range of 0–20 m. It can be divided into four underwater topographic zones (the central (outer Qinzhou Bay), eastern (Sanniang Bay), western (east of Fangcheng Port), and southern (outside of the bay) parts); (2) based on geomorphological features, the study area comprises four major submarine geomorphological units (i.e., tide-dominated delta, tidal sand ridge group, tidal scour troughs, and underwater slope) and two intertidal geomorphological Citation: Cao, C.; Cai, F.; Qi, H.; units (i.e., tidal flat and abrasion platforms); (3) sandy sediments are widely present in Qinzhou Zheng, Y.; Lu, H. -

EAST ASIA Unreached People Groups Prayer & Opportunities List

EAST ASIA Unreached People Groups Prayer & Opportunities List 2020 Priorities This SCBC resource is made possible through the Cooperative Program of South Carolina Baptist churches. Pictures used are compliments of the International Mission Board. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE UPG NAME POPULATION 3 Western Xiangxi Miao 1,600,000 4 PingDi Yao 1,610,000 5 Cao Miao (Mjuniang) 116,000 6 Central HongshuiHe Zhuang 1,080,000 7 HuiShui Miao 324,000 8 Northern Bai 870.000 9 Jiarong 311,000 10 Gui Bei Zhuang 1,475,000 11 Xiaoliang Shan Nosu 429,000 12 Ambdo Tibetans 1,355.000 13 Lolopo 618,000 READY TO GO? Opportunities exist for Churches to come and serve among these People Groups, doing short term mission trips. If you have interest to learn more about these trips, please contact Robert at: [email protected] Thank you for praying for these Unreached People Groups. GET UPDATES FOR INFO Have you joined Pray52? For information on Missions Text SCGo to 313131 to Partnerships and other resources to receive prayer requests on help your church fulfill the behalf of our SC Great Commission, contact: missionaries and East Asia South Carolina Baptist Convention partners every Wednesday! Missions Mobilization Team (803) 227-6026 e-mail: [email protected] www.scbaptist.org/send WESTERN XIANGXI MIAO Population: 1,600,000 Progress of the Gospel: Engaged but not reached Christianity: Dispersed CP Activity, < 2% reached They are part of the Miao nationality, but they speak a language different from all other Miao groups in China. Their dress and customs are also different.