Analysis Compared with Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HODGKIN LYMPHOMA TREATMENT REGIMENS (Part 1 of 2)

HODGKIN LYMPHOMA TREATMENT REGIMENS (Part 1 of 2) The selection, dosing, and administration of anticancer agents and the management of associated toxicities are complex. Drug dose modifications and schedule and initiation of supportive care interventions are often necessary because of expected toxicities and because of individual patient variability, prior treatment, and comorbidities. Thus, the optimal delivery of anticancer agents requires a healthcare delivery team experienced in the use of such agents and the management of associated toxicities in patients with cancer. The cancer treatment regimens below may include both FDA-approved and unapproved uses/regimens and are provided as references only to the latest treatment strategies. Clinicians must choose and verify treatment options based on the individual patient. NOTE: GREY SHADED BOXES CONTAIN UPDATED REGIMENS. REGIMEN DOSING Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma—First-Line Treatment General treatment note: Routine use of growth factors is not recommended. Leukopenia is not a factor for treatment delay or dose reduction (except for escalated BEACOPP).1 CR=complete response IPS=International Prognostic Score PD=progressive disease PFTs=pulmonary function tests PR=partial response RT=radiation therapy SD=stable disease Stage IA, IIA Favorable ABVD (doxorubicin [Adriamycin] Days 1 and 15: Doxorubicin 25mg/m2 IV + bleomycin 10mg/m2 IV + vinblastine + bleomycin + vinblastine + 6mg/m2 IV + dacarbazine 375mg/m2 IV. dacarbazine [DTIC-Dome]) + Repeat cycle every 4 weeks for 2–4 cycles. involved-field radiotherapy (IFRT)1–4 Follow with IFRT after completion of chemotherapy. Abbreviated Stanford V Weeks 1, 3, 5 and 7: Vinblastine 6mg/m2 IV + doxorubicin 25mg/m2 IV. (doxorubicin + vinblastine + Weeks 1 and 5: Mechlorethamine 6mg/m2. -

(Rituxan®), Rituximab-Abbs (Truxima®), Rituximab-Pvvr (Ruxience®) Prior Authorization Drug Coverage Policy

1 Rituximab Products: Rituximab (Rituxan®), Rituximab-abbs (Truxima®), Rituximab-pvvr (Ruxience®) Prior Authorization Drug Coverage Policy Effective Date: 2/1/2021 Revision Date: n/a Review Date: 7/2/20 Lines of Business: Commercial Policy type: Prior Authorization This Drug Coverage Policy provides parameters for the coverage of rituximab (Rituxan®), rituximab-abbs (Truxima®), and rituximab-pvvr (Ruxience®). Consideration of medically necessary indications are based upon U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indications, recommended uses within the Centers of Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) five recognized compendia, including the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Drugs & Biologics Compendium (Category 1 or 2A recommendations), and peer-reviewed scientific literature eligible for coverage according to the CMS, Medicare Benefit Policy Manual, Chapter 15, section 50.4.5 titled, “Off- Label Use of Anti-Cancer Drugs and Biologics.” This policy evaluates whether the drug therapy is proven to be effective based on published evidence-based medicine. Drug Description1-3 Rituximab (Rituxan®), rituximab-abbs (Truxima®), and rituximab-pvvr (Ruxience®) are monoclonal antibodies that target the CD20 antigen expressed on the surface of pre-B and mature B- lymphocytes. Upon binding to cluster of differentiation (CD) 20, rituximab mediates B-cell lysis. Possible mechanisms of cell lysis include complement dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) and antibody dependent cell mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC). B cells are believed to play a role in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and associated chronic synovitis. In this setting, B cells may be acting at multiple sites in the autoimmune/inflammatory process, including through production of rheumatoid factor (RF) and other autoantibodies, antigen presentation, T-cell activation, and/or proinflammatory cytokine production. -

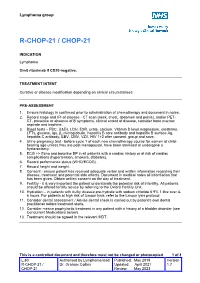

R-Chop-21 / Chop-21

Lymphoma group R-CHOP-21 / CHOP-21 INDICATION Lymphoma Omit rituximab if CD20-negative. TREATMENT INTENT Curative or disease modification depending on clinical circumstances PRE-ASSESSMENT 1. Ensure histology is confirmed prior to administration of chemotherapy and document in notes. 2. Record stage and IPI of disease - CT scan (neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis), and/or PET- CT, presence or absence of B symptoms, clinical extent of disease, consider bone marrow aspirate and trephine. 3. Blood tests – FBC, U&Es, LDH, ESR, urate, calcium, Vitamin D level,magnesium, creatinine, LFTs, glucose, Igs, β2 microglobulin, hepatitis B core antibody and hepatitis B surface Ag, hepatitis C antibody, EBV, CMV, VZV, HIV 1+2 after consent, group and save. 4. Urine pregnancy test • before cycle 1 of each new chemotherapy course for women of child- bearing age unless they are post-menopausal, have been sterilised or undergone a hysterectomy. 5. ECG +/- Echo and baseline BP in all patients with a cardiac history or at risk of cardiac complications (hypertension, smokers, diabetes). 6. Record performance status (WHO/ECOG). 7. Record height and weight. 8. Consent - ensure patient has received adequate verbal and written information regarding their disease, treatment and potential side effects. Document in medical notes all information that has been given. Obtain written consent on the day of treatment. 9. Fertility - it is very important the patient understands the potential risk of infertility. All patients should be offered fertility advice by referring to the Oxford Fertility Unit. 10. Hydration – in patients with bulky disease pre-hydrate with sodium chloride 0.9% 1 litre over 4- 6 hours. -

Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (ALCL)

Helpline (freephone) 0808 808 5555 [email protected] www.lymphoma-action.org.uk Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) This page is about anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL), a type of T-cell lymphoma. On this page What is ALCL? Who gets it? Symptoms Treatment Relapsed and refractory ALCL Research and targeted treatments We have separate information about the topics in bold font. Please get in touch if you’d like to request copies or if you would like further information about any aspect of lymphoma. Phone 0808 808 5555 or email [email protected]. What is ALCL? Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a type of T-cell lymphoma – a non-Hodgkin lymphoma that develops from white blood cells called T cells. Under a microscope, the cancerous cells in ALCL look large, undeveloped and very abnormal (‘anaplastic’). There are four main types of ALCL. They have complicated names based on their features and the types of proteins they make: • ALK-positive ALCL (also known as ALK+ ALCL) is the most common type. In ALK-positive ALCL, the abnormal T cells have a genetic change (mutation) that means they make a protein called ‘anaplastic lymphoma kinase’ (ALK). In other words, they test positive for ALK. ALK-positive ALCL is a fast-growing (high-grade) lymphoma. Page 1 of 6 © Lymphoma Action • ALK-negative ALCL (also known as ALK- ALCL) is a high-grade lymphoma that accounts for around 3 in every 10 cases of ALCL. The abnormal T cells do not make the ALK protein – they test negative for ALK. -

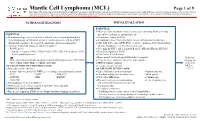

Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL)

Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL) Page 1 of 9 Disclaimer: This algorithm has been developed for MD Anderson using a multidisciplinary approach considering circumstances particular to MD Anderson’s specific patient population, services and structure, and clinical information. This is not intended to replace the independent medical or professional judgment of physicians or other health care providers in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine a patient's care. This algorithm should not be used to treat pregnant women. PATHOLOGIC DIAGNOSIS INITIAL EVALUATION ESSENTIAL: ● Physical exam: attention to node-bearing areas, including Waldeyer's ring, ESSENTIAL: size of liver and spleen, and patient’s age ● Hematopathology review of all slides with at least one tumor paraffin block. ● Performance status (ECOG) Hematopathology confirmation of classic versus aggressive variant of MCL ● B symptoms (fever, drenching night sweats, unintentional weight loss) (blastoid/pleomorphic). Re-biopsy if consult material is non-diagnostic. ● CBC with differential, LDH, BUN, creatinine, albumin, AST, total bilirubin, 1 ● Adequate immunophenotype to confirm diagnosis alkaline phosphatase, serum calcium, uric acid ○ Paraffin panel: ● Screening for HIV 1 and 2, hepatitis B and C (HBcAb, HBaAg, HCVAb) - Pan B-cell marker (CD19, CD20, PAX5), CD3, CD5, CD10, and cyclin D1 ● Beta-2 microglobulin (B2M) - Ki-67 (proliferation rate) ● Chest x-ray, PA and lateral or ● Bone marrow bilateral biopsy with unilateral aspirate Induction ○ Flow cytometry immunophenotyping: -

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines® ) Non-Hodgkin’S Lymphomas Version 2.2015

NCCN Guidelines Index NHL Table of Contents Discussion NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines® ) Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas Version 2.2015 NCCN.org Continue Version 2.2015, 03/03/15 © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2015, All rights reserved. The NCCN Guidelines® and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN® . Peripheral T-Cell Lymphomas NCCN Guidelines Version 2.2015 NCCN Guidelines Index NHL Table of Contents Peripheral T-Cell Lymphomas Discussion DIAGNOSIS SUBTYPES ESSENTIAL: · Review of all slides with at least one paraffin block representative of the tumor should be done by a hematopathologist with expertise in the diagnosis of PTCL. Rebiopsy if consult material is nondiagnostic. · An FNA alone is not sufficient for the initial diagnosis of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Subtypes included: · Adequate immunophenotyping to establish diagnosisa,b · Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), NOS > IHC panel: CD20, CD3, CD10, BCL6, Ki-67, CD5, CD30, CD2, · Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL)d See Workup CD4, CD8, CD7, CD56, CD57 CD21, CD23, EBER-ISH, ALK · Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), ALK positive (TCEL-2) or · ALCL, ALK negative > Cell surface marker analysis by flow cytometry: · Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) kappa/lambda, CD45, CD3, CD5, CD19, CD10, CD20, CD30, CD4, CD8, CD7, CD2; TCRαβ; TCRγ Subtypesnot included: · Primary cutaneous ALCL USEFUL UNDER CERTAIN CIRCUMSTANCES: · All other T-cell lymphomas · Molecular analysis to detect: antigen receptor gene rearrangements; t(2;5) and variants · Additional immunohistochemical studies to establish Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type (See NKTL-1) lymphoma subtype:βγ F1, TCR-C M1, CD279/PD1, CXCL-13 · Cytogenetics to establish clonality · Assessment of HTLV-1c serology in at-risk populations. -

Bendamustine Plus Rituximab: Is It a BRIGHT Idea?

Editorial Commentary Page 1 of 4 Bendamustine plus rituximab: is it a BRIGHT idea? Carlo Visco1, Francesca Maria Quaglia1, Chiara Bovo2, Maria Chiara Tisi3, Mauro Krampera1 1Department of Medicine, Section of Hematology, University of Verona, Verona, Italy; 2Medical Direction, University Hospital of Verona, Verona, Italy; 3Cell Therapy and Hematology, San Bortolo Hospital, Vicenza, Italy Correspondence to: Carlo Visco, MD. Associate Professor of Hematology, Department of Medicine, Section of Hematology, University of Verona, P.le L.A. Scuro 10, 37134 Verona, Italy. Email: [email protected]. Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned and reviewed by the Section Editor Xinyi Du (Department of Hematology, Northern Jiangsu People’s Hospital, Yangzhou, China). Comment on: Flinn IW, van der Jagt R, Kahl B, et al. First-Line Treatment of Patients With Indolent Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma or Mantle-Cell Lymphoma With Bendamustine Plus Rituximab Versus R-CHOP or R-CVP: Results of the BRIGHT 5-Year Follow-Up Study. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:984-91. Submitted Sep 20, 2019. Accepted for publication Oct 14, 2019. doi: 10.21037/cco.2019.10.03 View this article at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cco.2019.10.03 Flinn et al. have reported the results of the long-term in the BRIGHT study were eagerly awaited. As the Stil- follow-up for the BRIGHT trial, an international study 1 trial, the BRIGHT study (3) included patients with which compared the efficacy and the safety of bendamustine follicular lymphoma (grade 1 or 2, excluding grade 3A), plus rituximab (BR) with either rituximab plus lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, splenic marginal zone B-cell cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone lymphoma, extranodal marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) (R-CHOP) or rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, vincristine, of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type, nodal marginal and prednisone (R-CVP) for treatment-naive patients with zone B-cell lymphoma (371 patients with iNHL), or MCL indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (iNHL) or mantle-cell (74 patients). -

Treating Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma If You’Ve Been Diagnosed with Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, Your Treatment Team Will Discuss Your Options with You

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Treating Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma If you’ve been diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, your treatment team will discuss your options with you. It’s important to weigh the benefits of each treatment option against the possible risks and side effects. How is non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated? Depending on the type and stage (extent) of the lymphoma and other factors, treatment options for people with NHL might include: ● Chemotherapy for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma ● Immunotherapy for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma ● Targeted Drug Therapy for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma ● Radiation Therapy for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma ● High-Dose Chemotherapy and Stem Cell Transplant for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma ● Surgery for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Common treatment approaches Treatment approaches for NHL depend on the type of cancer, how advanced it is, as well as your health and other factors. Another important part of treatment for many people is palliative or supportive care. This can help prevent or treat problems such as infections, low blood cell counts, or some symptoms caused by the lymphoma. ● Treating B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma ● Treating T-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma ● Treating HIV-Associated Lymphoma 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 ● Palliative and Supportive Care for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Who treats non-Hodgkin lymphoma? Based on your treatment options, you may have different types of doctors on your treatment team. These doctors could include: ● A medical oncologist or hematologist: a doctor who treats lymphoma with chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy. ● A radiation oncologist: a doctor who treats cancer with radiation therapy. ● A bone marrow transplant doctor: a doctor who specializes in treating cancer or other diseases with bone marrow or stem cell transplants. -

Histological Transformation in Duodenal-Type Follicular Lymphoma: a Case Report and Review of the Literature

www.oncotarget.com Oncotarget, 2019, Vol. 10, (No. 36), pp: 3424-3429 Case Report Histological transformation in duodenal-type follicular lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature Tomohiko Tanigawa1, Ryohei Abe1, Jun Kato1, Naoki Hosoe2, Haruhiko Ogata2, Kaori Kameyama3, Shinichiro Okamoto1 and Takehiko Mori1 1Division of Hematology, Department of Medicine, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan 2Center for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Endoscopy, Keio University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan 3Department of Diagnostic Pathology, Keio University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan Correspondence to: Takehiko Mori, email: [email protected] Keywords: duodenal-type follicular lymphoma; histological transformation; duodenum; chemotherapy; prognosis Received: February 13, 2019 Accepted: April 14, 2019 Published: May 21, 2019 Copyright: Tanigawa et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC BY 3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. ABSTRACT Duodenal-type follicular lymphoma (DFL) is a rare variant of follicular lymphoma (FL) characterized by distinctive clinical features such as localization and favorable prognosis. We herein report a case of DFL in which histological transformation into diffuse large B-cell lymphoma developed 7 years after diagnosis. The transformed lymphoma was refractory to chemotherapy, and the patient passed away due to disease progression. To date, there have been only a limited number of reported cases of histological transformation of DFL, and the clinical outcomes of those cases except our present case have been favorable, with good responses to chemotherapy. Although the histological transformation of DFL is a rare event, the clinical course of the present case suggested that it would be a fatal event and underscore the importance of the life-long management of DFL. -

(R2-CHOP) in Patients with B-Cell Lymphoma

Letters to the Editor 252 Table 1. Results of multivariate analysis for event-free survival, overall REFERENCES survival and relapse-free survival 1 Hasle H, Clemmensen IH, Mikkelsen M. Risks of leukaemia and solid tumours in individuals with Down’s syndrome. Lancet 2000; 355: 165–169. Outcome Variable HR 95% CI P-value 2 Whitlock JA, Sather HN, Gaynon P, Robison LL, Wells RJ, Trigg M et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of children with Down syndrome and acute lympho- EFS BTG1 1.97 0.57–6.84 0.29 blastic leukemia: a Children’s Cancer Group study. Blood 2005; 106: 4043–4049. IKZF1 2.45 1.18–5.07 0.02 3 Buitenkamp T, Forestier E, Heerema NA, van den Heuvel MM, Pieters R, de Haas V ETV6–RUNX1 0.22 0.03–1.74 0.15 et al. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in children with Down Syndrome: a report from WBC X50 Â 109 2.55 0.88–7.39 0.08 the Ponti di Legno Study group. ASH: San Diego, 2011. Age X10 years 1.29 0.59–2.85 0.52 4 Forestier E, Izraeli S, Beverloo B, Haas O, Pession A, Michalova K et al. Cytogenetic features of acute lymphoblastic and myeloid leukemias in pediatric patients with OS BTG1 2.24 0.63–7.91 0.21 Down syndrome: an iBFM-SG study. Blood 2008; 111: 1575–1583. IKZF1 2.02 0.95–4.29 0.06 5 Hertzberg L, Vendramini E, Ganmore I, Cazzaniga G, Schmitz M, Chalker J et al. ETV6–RUNX1 0.21 0.03–1.67 0.14 Down syndrome acute lymphoblastic leukemia, a highly heterogeneous disease WBC X50 Â 109 2.49 0.85–7.26 0.09 in which aberrant expression of CRLF2 is associated with mutated JAK2: a report AgeX 10 years 1.20 0.52–2.76 0.66 from the International BFM Study Group. -

Pre-HCT Treatment for Hodgkin's / Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma

Appendix T Pre-HCT Treatment for Hodgkin’s / Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma This appendix is intended to provide additional information on: Common pre-HCT treatments for lymphoma, Lines of therapy, Cycles, and How to report the best response to lines of therapies. NOTE: Reporting second or subsequent stem cell transplants When using the Hodgkin’s and Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Pre-HCT Data Form (2018) to report a second or subsequent transplant, please check the box at the top of the form and continue with question 129. Lines of therapy questions do not need to be completed for second or subsequent transplants. Common Pre-HCT Treatments Chemotherapy: The following chemotherapy regimens are common initial and salvage treatments for Hodgkin’s / Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Common Chemotherapy Regimens Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Nitrogen Mustard (mustine, mechlorethamine) Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) MOPP Vincristine (VCR, Oncovin) CVP Vincristine (VCR, Oncovin) Procarbazine (Mutalane) Prednisone* Prednisone* Doxorubicin (Adriamycin) Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) Vinblastine (Velban, VLB) Doxorubicin (Adriamycin) ABVD CHOP Bleomycin (BLM, Blenoxane) Vincristine (VCR, Oncovin) Dacarbazine (DTIC) Prednisone* Bleomycin (BLM, Blenoxane) Etoposide (VP-16, VePesid) Doxorubicin (Adriamycin) Fludarabine (Fludara) BEACOPP Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) FND Mitoxantrone (Novantrone) Vincristine (VCR, Oncovin) Dexamethasone* Procarbazine (Mutalane) Prednisone* Etoposide (VP-16, VePesid) Vinblastine (Velban, VLB) Methylprednisolone* VBM Bleomycin (BLM, Blenoxane) -

How We Manage Follicular Lymphoma

Leukemia (2014) 28, 1388–1395 OPEN & 2014 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0887-6924/14 www.nature.com/leu HOW TO MANAGE... How we manage follicular lymphoma W Hiddemann1 and BD Cheson2 Major changes have taken place within the last few years in the management of follicular lymphoma (FL) leading to substantial improvement in prognosis and overall survival. For some patients with limited disease stages I and II, radiotherapy may be associated with durable responses; however, it is unclear whether patients are cured and new approaches such as the combination of irradiation with rituximab or even single-agent rituximab need to be explored. Whereas watch and wait is the current standard for stage III and IV disease with low tumour burden, better indices are warranted to potentially select patients for whom early intervention is preferred. For advanced stages with a high tumour burden, immunochemotherapy followed by 2 years of rituximab maintenance is widely accepted as standard therapy, although re-treatment at recurrence may be an alternative option. Highly attractive new therapeutic options have recently arisen from new antibodies, and from new agents targeting oncogenic pathways such as B-cell receptor signalling pathways or inhibition of bcl 2. Furthermore, immunomodulatory drugs may add to the therapeutic armamentarium and may lead to ‘chemotherapy-free’ therapies in the near future. Hence, the management of FLs has become a moving target and the hope is justified that the long-term perspectives of patients suffering from the disease will be further improved in the near future. Leukemia (2014) 28, 1388–1395; doi:10.1038/leu.2014.91 INTRODUCTION stages III and IV.