Treating Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma If You’Ve Been Diagnosed with Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, Your Treatment Team Will Discuss Your Options with You

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antineoplastic Agents

bmchp.org | 888-566-0008 wellsense.org | 877-957-1300 Pharmacy Policy Antineoplastic Agents Policy Number: 9.700 Version Number: 2.0 Version Effective Date: 9/1/2021 Product Applicability All Plan+ Products Well Sense Health Plan Boston Medical Center HealthNet Plan New Hampshire Medicaid MassHealth- MCO MassHealth- ACO Qualified Health Plans/ConnectorCare/Employer Choice Direct Senior Care Options Note: Disclaimer and audit information is located at the end of this document. Prior Authorization Policy Products Affected: Daurismo™ (glasdegib tablet) Rubraca™ (rucaparib tablets) Erleada™ (apalutamide tablet) Sarclisa® (Isatuximab–IRFC injection) Farydak® (panobinostat capsule) Tazverik™ (tazemetostat tablet) Folotyn® (pralatrexate injection) Talzenna® (talazoparib capsule) Gleostine™ (lomustine capsule) Tibsovo® (ivosidenib tablet) Idhifa® (enasidenib mesylate tablet) Ukoniq (umbralisib tosylate tablet) Lonsurf® (tipiracil hcl and trifluridine tablet) Valchlor™ (mechlorethamine gel) Lynparza™ (olaparib capsule, and tablets) Zejula™ (niraparib capsules) Ninlaro® (ixazomib capsule) Zelboraf® (vemurafenib tablet) Odomzo® (sonidegib capsules) Zytiga® (abiraterone acetate tablet) Pomalyst® (pomalidomide capsule) + Plan refers to Boston Medical Center Health Plan, Inc. and its affiliates and subsidiaries offering health coverage plans to enrolled members. The Plan operates in Massachusetts under the trade name Boston Medical Center HealthNet Plan and in other states under the trade name Well Sense Health Plan. Antineoplastic Agents 1 of 4 The Plan may authorize coverage of the above products for members meeting the following criteria: Covered FDA approved indication Use Use supported by: o American Hospital Formulary Service Drug Information o DRUGDEX Information System o United States Pharmacopeia- Drug Information o National Comprehensive Cancer Network (categories 1,2a, and 2b) Medically accepted indications will also be considered for approval. -

Genmab and ADC Therapeutics Announce Amended Agreement for Camidanlumab Tesirine (Cami)

Genmab and ADC Therapeutics Announce Amended Agreement for Camidanlumab Tesirine (Cami) Media Release Copenhagen, Denmark and Lausanne, Switzerland, October 30, 2020 • ADC Therapeutics to continue the development and commercialization of Cami • Genmab to receive mid-to-high single-digit tiered royalty Genmab A/S (Nasdaq: GMAB) and ADC Therapeutics SA (NYSE: ADCT) today announced that they have executed an amended agreement for ADC Therapeutics to continue the development and commercialization of camidanlumab tesirine (Cami). The parties first entered into a collaboration and license agreement in June 2013 for the development of Cami, an antibody drug conjugate (ADC) which combines Genmab’s HuMax®-TAC antibody targeting CD25 with ADC Therapeutics’ highly potent pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) warhead technology. Under the terms of the 2013 agreement, the parties were to determine the path forward for continued development and commercialization of Cami upon completion of a Phase 1a/b clinical trial. ADC Therapeutics previously announced that Cami achieved an overall response rate of 86.5%, including a complete response rate of 48.6%, in Hodgkin lymphoma patients in this trial who had received a median of five prior lines of therapy. Cami is currently being evaluated in a 100-patient pivotal Phase 2 clinical trial intended to support the submission of a Biologics License Application (BLA) to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The trial is more than 50 percent enrolled and ADC Therapeutics anticipates reporting interim results in the first half of 2021. “We have a long-standing relationship with the ADC Therapeutics team and believe they are an ideal partner for the ongoing development and potential commercialization of Cami,” said Jan van de Winkel, Ph.D., Chief Executive Officer of Genmab. -

Duvelisib Eliminates CLL B Cells, Impairs CLL- Supporting Cells, and Overcomes Ibrutinib Resistance in Preclinical Models

Duvelisib Eliminates CLL B Cells, Impairs CLL- Supporting Cells, and Overcomes Ibrutinib Resistance in Preclinical Models Shih-Shih Chen ( [email protected] ) Karches Center for Oncology Research, the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research Jacqueline Barrientos Karches Center for Oncology Research, the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research Gerardo Ferrer Josep Carreras Leukaemia Research Institute (IJC) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4084-6815 Priyadarshini Ravichandran Karches Center for Oncology Research, the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research Michael Ibrahim Karches Center for Oncology Research, the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research Yasmine Kieso Karches Center for Oncology Research, the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research Jeff Kutok Innity Pharmaceuticals Marisa Peluso Innity Pharmaceuticals, Inc Sujata Sharma Innity Pharmaceuticals, Inc David Weaver Institute of Health Sciences, Anhui University Jonathan Pachter Verastem Inc. Kanti Rai The Karches Center for Oncology Research. The Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research. Nicholas Chiorazzi Karches Center for Oncology Research, the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research Article Keywords: chronic lymphocytic leukemia, cancer therapy, Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase (BTKi), phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3Ki) Page 1/23 Posted Date: July 21st, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-701669/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 2/23 Abstract Inhibitors of Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase (BTKi) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3Ki) have signicantly improved therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). However, the emergence of resistance to BTKi has introduced an unmet therapeutic need. Here we demonstrate in vitro and in vivo the essential roles of PI3K-δ for CLL B-cell survival and migration and of PI3K-γ in T-cell migration and macrophage polarization; and more ecacious inhibition in CLL-cell burden by dual inhibition of PI3K-δ,γ. -

PI3K Inhibitors in Cancer: Clinical Implications and Adverse Effects

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review PI3K Inhibitors in Cancer: Clinical Implications and Adverse Effects Rosalin Mishra , Hima Patel, Samar Alanazi , Mary Kate Kilroy and Joan T. Garrett * Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45267-0514, USA; [email protected] (R.M.); [email protected] (H.P.); [email protected] (S.A.); [email protected] (M.K.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-513-558-0741; Fax: +1-513-558-4372 Abstract: The phospatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) pathway is a crucial intracellular signaling pathway which is mutated or amplified in a wide variety of cancers including breast, gastric, ovarian, colorectal, prostate, glioblastoma and endometrial cancers. PI3K signaling plays an important role in cancer cell survival, angiogenesis and metastasis, making it a promising therapeutic target. There are several ongoing and completed clinical trials involving PI3K inhibitors (pan, isoform-specific and dual PI3K/mTOR) with the goal to find efficient PI3K inhibitors that could overcome resistance to current therapies. This review focuses on the current landscape of various PI3K inhibitors either as monotherapy or in combination therapies and the treatment outcomes involved in various phases of clinical trials in different cancer types. There is a discussion of the drug-related toxicities, challenges associated with these PI3K inhibitors and the adverse events leading to treatment failure. In addition, novel PI3K drugs that have potential to be translated in the clinic are highlighted. Keywords: cancer; PIK3CA; resistance; PI3K inhibitors Citation: Mishra, R.; Patel, H.; Alanazi, S.; Kilroy, M.K.; Garrett, J.T. -

A Prospective, Multicenter, Phase-II Trial of Ibrutinib Plus Venetoclax In

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Open HOVON 141 CLL Version 4, 20 DEC 2018 A prospective, multicenter, phase-II trial of ibrutinib plus venetoclax in patients with creatinine clearance ≥ 30 ml/min who have relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (RR-CLL) with or without TP53 aberrations HOVON 141 CLL / VIsion Trial of the HOVON and Nordic CLL study groups PROTOCOL Principal Investigator : Arnon P Kater (HOVON) Carsten U Niemann (Nordic CLL study Group)) Sponsor : HOVON EudraCT number : 2016-002599-29 ; Page 1 of 107 Levin M-D, et al. BMJ Open 2020; 10:e039168. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039168 BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Open Levin M-D, et al. BMJ Open 2020; 10:e039168. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039168 BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Open HOVON 141 CLL Version 4, 20 DEC 2018 LOCAL INVESTIGATOR SIGNATURE PAGE Local site name: Signature of Local Investigator Date Printed Name of Local Investigator By my signature, I agree to personally supervise the conduct of this study in my affiliation and to ensure its conduct in compliance with the protocol, informed consent, IRB/EC procedures, the Declaration of Helsinki, ICH Good Clinical Practices guideline, the EU directive Good Clinical Practice (2001-20-EG), and local regulations governing the conduct of clinical studies. -

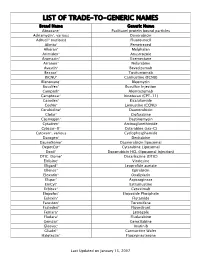

Trade-To-Generic Names

LIST OF TRADE-TO-GENERIC NAMES Brand Name Generic Name Abraxane® Paclitaxel protein bound particles Adriamycin®, various Doxorubicin Adrucil® (various) Fluorouracil Alimta® Pemetrexed Alkeran® Melphalan Arimidex® Anastrozole Aromasin® Exemestane Arranon® Nelarabine Avastin® Bevacizumab Bexxar® Tositumomab BiCNU® Carmustine (BCNU) Blenoxane® Bleomycin Busulfex® Busulfan Injection Campath® Alemtuzumab Camptosar® Irinotecan (CPT-11) Casodex® Bicalutamide CeeNu® Lomustine (CCNU) Cerubidine® Daunorubicin Clolar® Clofarabine Cosmegen® Dactinomycin Cytadren® Aminoglutethimide Cytosar-U® Cytarabine (ara-C) Cytoxan®, various Cyclophosphamide Dacogen® Decitabine DaunoXome® Daunorubicin liposomal DepotCyt® Cytarabine Liposomal Doxil® Doxorubicin HCL (liposomal injection) DTIC-Dome® Dacarbazine (DTIC) Eldisine® Vindesine Eligard® Leuprolide acetate Ellence® Epirubicin Eloxatin® Oxaliplatin Elspar® Asparaginase EmCyt® Estramustine Erbitux® Cetuximab Etopofos® Etoposide Phosphate Eulexin® Flutamide Fareston® Toremifene Faslodex® Fluvestrant Femara® Letrozole Fludara® Fludarabine Gemzar® Gemcitabine Gleevec® Imatinib Gliadel® Carmustine Wafer Halotestin® Fluoxymesterone Last Updated on January 15, 2007 Brand Name Generic Name Herceptin® Trastuzumab Hexalen® Altretamine Hycamtin® Topotecan Hydrea® Hydroxyurea Idamycin® Idarubicin Ifex® Ifosfamide Intron A® Interferon alfa-2b Iressa® Gefitinib Leukeran® Chlorambucil Leukine® Sargramostim Leustatin® Cladribine Lupron depot® Leuprolide acetate depot Lupron® Leuprolide acetate Matulane® Procarbazine Megace® -

Minutes of the CHMP Meeting 14-17 September 2020

13 January 2021 EMA/CHMP/625456/2020 Corr.1 Human Medicines Division Committee for medicinal products for human use (CHMP) Minutes for the meeting on 14-17 September 2020 Chair: Harald Enzmann – Vice-Chair: Bruno Sepodes Disclaimers Some of the information contained in these minutes is considered commercially confidential or sensitive and therefore not disclosed. With regard to intended therapeutic indications or procedure scopes listed against products, it must be noted that these may not reflect the full wording proposed by applicants and may also vary during the course of the review. Additional details on some of these procedures will be published in the CHMP meeting highlights once the procedures are finalised and start of referrals will also be available. Of note, these minutes are a working document primarily designed for CHMP members and the work the Committee undertakes. Note on access to documents Some documents mentioned in the minutes cannot be released at present following a request for access to documents within the framework of Regulation (EC) No 1049/2001 as they are subject to on- going procedures for which a final decision has not yet been adopted. They will become public when adopted or considered public according to the principles stated in the Agency policy on access to documents (EMA/127362/2006). 1 Addition of the list of participants Official address Domenico Scarlattilaan 6 ● 1083 HS Amsterdam ● The Netherlands Address for visits and deliveries Refer to www.ema.europa.eu/how-to-find-us Send us a question Go to www.ema.europa.eu/contact Telephone +31 (0)88 781 6000 An agency of the European Union © European Medicines Agency, 2020. -

Draft Minutes PDCO 12-15 November 2019

11 December 2019 EMA/PDCO/615413/2019 Inspections, Human Medicines Pharmacovigilance and Committees Division Paediatric Committee (PDCO) Minutes for the meeting on 12-15 November 2019 Chair: Koenraad Norga – Vice-Chair: Sabine Scherer Health and safety information In accordance with the Agency’s health and safety policy, delegates are to be briefed on health, safety and emergency information and procedures prior to the start of the meeting. Disclaimers Some of the information contained in these minutes is considered commercially confidential or sensitive and therefore not disclosed. With regard to intended therapeutic indications or procedure scopes listed against products, it must be noted that these may not reflect the full wording proposed by applicants and may also vary during the course of the review. Additional details on some of these procedures will be published in the PDCO Committee meeting reports (after the PDCO Opinion is adopted), and on the Opinions and decisions on paediatric investigation plans webpage (after the EMA Decision is issued). Of note, this set of minutes is a working document primarily designed for PDCO members and the work the Committee undertakes. Further information with relevant explanatory notes can be found at the end of this document. Note on access to documents Some documents mentioned in these minutes cannot be released at present following a request for access to documents within the framework of Regulation (EC) No 1049/2001 as they are subject to on- going procedures for which a final decision has not yet been adopted. They will become public when adopted or considered public according to the principles stated in the Agency policy on access to documents (EMA/127362/2006). -

Childhood Leukemia

Onconurse.com Fact Sheet Childhood Leukemia The word leukemia literally means “white blood.” fungi. WBCs are produced and stored in the bone mar- Leukemia is the term used to describe cancer of the row and are released when needed by the body. If an blood-forming tissues known as bone marrow. This infection is present, the body produces extra WBCs. spongy material fills the long bones in the body and There are two main types of WBCs: produces blood cells. In leukemia, the bone marrow • Lymphocytes. There are two types that interact to factory creates an overabundance of diseased white prevent infection, fight viruses and fungi, and pro- cells that cannot perform their normal function of fight- vide immunity to disease: ing infection. As the bone marrow becomes packed with diseased white cells, production of red cells (which ° T cells attack infected cells, foreign tissue, carry oxygen and nutrients to body tissues) and and cancer cells. platelets (which help form clots to stop bleeding) slows B cells produce antibodies which destroy and stops. This results in a low red blood cell count ° foreign substances. (anemia) and a low platelet count (thrombocytopenia). • Granulocytes. There are four types that are the first Leukemia is a disease of the blood defense against infection: Blood is a vital liquid which supplies oxygen, food, hor- ° Monocytes are cells that contain enzymes that mones, and other necessary chemicals to all of the kill foreign bacteria. body’s cells. It also removes toxins and other waste products from the cells. Blood helps the lymph system ° Neutrophils are the most numerous WBCs to fight infection and carries the cells necessary for and are important in responding to foreign repairing injuries. -

Proteomics and Drug Repurposing in CLL Towards Precision Medicine

cancers Review Proteomics and Drug Repurposing in CLL towards Precision Medicine Dimitra Mavridou 1,2,3, Konstantina Psatha 1,2,3,4,* and Michalis Aivaliotis 1,2,3,4,* 1 Laboratory of Biochemistry, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, GR-54124 Thessaloniki, Greece; [email protected] 2 Functional Proteomics and Systems Biology (FunPATh)—Center for Interdisciplinary Research and Innovation (CIRI-AUTH), GR-57001 Thessaloniki, Greece 3 Basic and Translational Research Unit, Special Unit for Biomedical Research and Education, School of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, GR-54124 Thessaloniki, Greece 4 Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, Foundation of Research and Technology, GR-70013 Heraklion, Greece * Correspondence: [email protected] (K.P.); [email protected] (M.A.) Simple Summary: Despite continued efforts, the current status of knowledge in CLL molecular pathobiology, diagnosis, prognosis and treatment remains elusive and imprecise. Proteomics ap- proaches combined with advanced bioinformatics and drug repurposing promise to shed light on the complex proteome heterogeneity of CLL patients and mitigate, improve, or even eliminate the knowledge stagnation. In relation to this concept, this review presents a brief overview of all the available proteomics and drug repurposing studies in CLL and suggests the way such studies can be exploited to find effective therapeutic options combined with drug repurposing strategies to adopt and accost a more “precision medicine” spectrum. Citation: Mavridou, D.; Psatha, K.; Abstract: CLL is a hematological malignancy considered as the most frequent lymphoproliferative Aivaliotis, M. Proteomics and Drug disease in the western world. It is characterized by high molecular heterogeneity and despite the Repurposing in CLL towards available therapeutic options, there are many patient subgroups showing the insufficient effectiveness Precision Medicine. -

And High-Dose Cyclophosphamide

141-146 6/6/06 13:01 Page 141 ONCOLOGY REPORTS 16: 141-146, 2006 141 Different mechanisms for anti-tumor effects of low- and high-dose cyclophosphamide YASUHIDE MOTOYOSHI1,2, KAZUHISA KAMINODA1,3, OHKI SAITOH1, KEISUKE HAMASAKI2, KAZUHIKO NAKAO3, NOBUKO ISHII3, YUJI NAGAYAMA1 and KATSUMI EGUCHI2 Departments of 1Medical Gene Technology, Atomic Bomb Disease Institute; 2Division of Immunology, Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Medical and Dental Sciences, and 3Division of Clinical Pharmaceutics and Health Research Center, Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, 1-12-4 Sakamoto, Nagasaki 852-8501, Japan Received February 3, 2006; Accepted April 7, 2006 Abstract. It is known that, besides its direct cytotoxic effect appear to be highly crucial in a clinical setting of combined as an alkylating chemotherapeutic agent, cyclophosphamide chemotherapy and immunotherapy for cancer treatment. also has immuno-modulatory effects, such as depletion of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. However, its optimal concen- Introduction tration has not yet been fully elucidated. Therefore, we first compared the effects of different doses of cyclophosphamide Chemotherapy and immunotherapy are generally regarded on T cell subsets including CD4+CD25+ T cells in mice. as unrelated or even mutually exclusive in cancer treatment, Cyclophosphamide (20 mg/kg) decreased the numbers of because chemotherapy kills not only target cancer cells but splenocytes, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by ~50%, while a decline also immune cells, inducing systemic immune suppression in CD4+CD25+ T cell number was more profound, leading to and dampening the therapeutic efficacy of immunotherapy. the remarkably lower ratios of CD4+CD25+ T cells to CD4+ In this regard, however, cyclophosphamide appears an T cells. -

Late Effects Among Long-Term Survivors of Childhood Acute Leukemia in the Netherlands: a Dutch Childhood Leukemia Study Group Report

0031-3998/95/3805-0802$03.00/0 PEDIATRIC RESEARCH Vol. 38, No.5, 1995 Copyright © 1995 International Pediatric Research Foundation, Inc. Printed in U.S.A. Late Effects among Long-Term Survivors of Childhood Acute Leukemia in The Netherlands: A Dutch Childhood Leukemia Study Group Report A. VAN DER DOES-VAN DEN BERG, G. A. M. DE VAAN, J. F. VAN WEERDEN, K. HAHLEN, M. VAN WEEL-SIPMAN, AND A. J. P. VEERMAN Dutch Childhood Leukemia Study Group,' The Hague, The Netherlands A.8STRAC ' Late events and side effects are reported in 392 children cured urogenital, or gastrointestinal tract diseases or an increased vul of leukemia. They originated from 1193 consecutively newly nerability of the musculoskeletal system was found. However, diagnosed children between 1972 and 1982, in first continuous prolonged follow-up is necessary to study the full-scale late complete remission for at least 6 y after diagnosis, and were effects of cytostatic treatment and radiotherapy administered treated according to Dutch Childhood Leukemia Study Group during childhood. (Pediatr Res 38: 802-807, 1995) protocols (70%) or institutional protocols (30%), all including cranial irradiation for CNS prophylaxis. Data on late events (relapses, death in complete remission, and second malignancies) Abbreviations were collected prospectively after treatment; late side effects ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia were retrospectively collected by a questionnaire, completed by ANLL, acute nonlymphocytic leukemia the responsible pediatrician. The event-free survival of the 6-y CCR, continuous first complete remission survivors at 15 y after diagnosis was 92% (±2%). Eight late DCLSG, Dutch Childhood Leukemia Study Group relapses and nine second malignancies were diagnosed, two EFS, event free survival children died in first complete remission of late toxicity of HR, high risk treatment, and one child died in a car accident.