NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines® ) Non-Hodgkin’S Lymphomas Version 2.2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primary Mediastinal Large B-Cell Lymphoma

Primary Mediastinal Large B-Cell Lymphoma Page 1 of 13 Disclaimer: This algorithm has been developed for MD Anderson using a multidisciplinary approach considering circumstances particular to MD Anderson’s specific patient population, services and structure, and clinical information. This is not intended to replace the independent medical or professional judgment of physicians or other health care providers in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine a patient's care. This algorithm should not be used to treat pregnant women. Note: Consider Clinical Trials as treatment options for eligible patients. PATHOLOGIC DIAGNOSIS INITIAL EVALUATION ESSENTIAL: 5 ● Physical exam: attention to node-bearing areas, including Waldeyer's ring, ESSENTIAL: and to size of liver and spleen ● ECOG performance status ● Hematopathology review of all slides with at least one paraffin ● B symptoms (Unexplained fever >38°C during the previous month; block or 15 unstained slides representative of the tumor. Rebiopsy if Recurrent drenching night sweats during the previous month; Weight consult material is nondiagnostic. loss >10 percent of body weight ≤ 6 months of diagnosis) ● Adequate morphology and immunophenotyping to establish 1 ● CBC with differential, LDH, BUN, creatinine, albumin, AST, diagnosis ALT, total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, serum calcium, uric acid ○ Paraffin Panel: CD3, CD20 and/or another pan-B-cell marker ● Beta 2 microglobulin (CD19, PAX-5, CD79a) or ● Screening for HIV 1 and 2, hepatitis B and C (HBcAb, HBsAg, HCV -

Follicular Lymphoma

Follicular Lymphoma What is follicular lymphoma? Let us explain it to you. www.anticancerfund.org www.esmo.org ESMO/ACF Patient Guide Series based on the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines FOLLICULAR LYMPHOMA: A GUIDE FOR PATIENTS PATIENT INFORMATION BASED ON ESMO CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES This guide for patients has been prepared by the Anticancer Fund as a service to patients, to help patients and their relatives better understand the nature of follicular lymphoma and appreciate the best treatment choices available according to the subtype of follicular lymphoma. We recommend that patients ask their doctors about what tests or types of treatments are needed for their type and stage of disease. The medical information described in this document is based on the clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) for the management of newly diagnosed and relapsed follicular lymphoma. This guide for patients has been produced in collaboration with ESMO and is disseminated with the permission of ESMO. It has been written by a medical doctor and reviewed by two oncologists from ESMO including the lead author of the clinical practice guidelines for professionals, as well as two oncology nurses from the European Oncology Nursing Society (EONS). It has also been reviewed by patient representatives from ESMO’s Cancer Patient Working Group. More information about the Anticancer Fund: www.anticancerfund.org More information about the European Society for Medical Oncology: www.esmo.org For words marked with an asterisk, a definition is provided at the end of the document. Follicular Lymphoma: a guide for patients - Information based on ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines – v.2014.1 Page 1 This document is provided by the Anticancer Fund with the permission of ESMO. -

Follicular Lymphoma with Leukemic Phase at Diagnosis: a Series Of

Leukemia Research 37 (2013) 1116–1119 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Leukemia Research journa l homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/leukres Follicular lymphoma with leukemic phase at diagnosis: A series of seven cases and review of the literature a c c c c Brady E. Beltran , Pilar Quinones˜ , Domingo Morales , Jose C. Alva , Roberto N. Miranda , d e e b,∗ Gary Lu , Bijal D. Shah , Eduardo M. Sotomayor , Jorge J. Castillo a Department of Oncology and Radiotherapy, Edgardo Rebagliati Martins Hospital, Lima, Peru b Division of Hematology and Oncology, Rhode Island Hospital, Brown University Alpert Medical School, Providence, RI, USA c Department of Pathology, Edgardo Rebaglati Martins Hospital, Lima, Peru d Department of Hematopathology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA e Department of Malignant Hematology, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, Tampa, FL, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Follicular lymphoma (FL) is a prevalent type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the United States and Europe. Received 23 April 2013 Although, FL typically presents with nodal involvement, extranodal sites are less common, and leukemic Received in revised form 25 May 2013 phase at diagnosis is rare. There is mounting evidence that leukemic presentation portends a worse Accepted 26 May 2013 prognosis in patients with FL. We describe 7 patients with a pathological diagnosis of FL who presented Available online 20 June 2013 with a leukemic phase. We compared our cases with 24 additional cases reported in the literature. Based on our results, patients who present with leukemic FL tend to have higher risk disease. -

Ilite™ ADCC Target CD20 (-) Assay Ready Cells (REF: BM4015)

PRODUCT SPECIFICATION iLite™ ADCC Target CD20 (-) Assay Ready Cells (REF: BM4015) Description iLite™ ADCC Target CD20 (-) Assay Ready Cells are based on a human B lymphocyte cell line, Raji (ATCC# CCL-86), and have been genetically engineered and optimized to be depleted of CD20 expression. The cells are to be use as negative controls together with iLite™ ADCC Effector (V) Assay Ready Cells and iLite™ ADCC Target CD20 (+) Assay Ready Cells for measuring the ADCC activity of anti-CD20 antibodies. Content >250 µL of iLite™ Assay Ready Cells suspended in RPMI 1640 with 20% FBS, mixed 1:1 with cryoprotective medium from Lonza (Cat. No 12-132A). Receipt and storage Upon receipt confirm that adequate dry-ice is present and the cells are frozen. Immediately transfer to -80°C storage. Cells should be stored at -80°C (do not store at any other temperature) and are stable as supplied until the expiry date shown. Cells should be used within 30 min of thawing. Background Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) is a mechanism whereby pathogenic cells are lysed by lymphocytes, most often Natural Killer (NK) cells. The mechanism involves binding of antibodies to surface antigens on the pathogen. Crosslinking of these antibodies to NK cells through the binding of the Fc-portion to Fc receptors on the NK cells leads to activation of the NK cell and formation of an immune synapse with the pathogenic cell. The NK cell releases cytotoxic granules containing granzymes and perforin into the synapse, leading to apoptosis of the targeted cell (1). The idea of employing ADCC to destroy dysfunctional cells by treating patients with antibodies has existed since the discovery of the ADCC mechanism. -

HODGKIN LYMPHOMA TREATMENT REGIMENS (Part 1 of 2)

HODGKIN LYMPHOMA TREATMENT REGIMENS (Part 1 of 2) The selection, dosing, and administration of anticancer agents and the management of associated toxicities are complex. Drug dose modifications and schedule and initiation of supportive care interventions are often necessary because of expected toxicities and because of individual patient variability, prior treatment, and comorbidities. Thus, the optimal delivery of anticancer agents requires a healthcare delivery team experienced in the use of such agents and the management of associated toxicities in patients with cancer. The cancer treatment regimens below may include both FDA-approved and unapproved uses/regimens and are provided as references only to the latest treatment strategies. Clinicians must choose and verify treatment options based on the individual patient. NOTE: GREY SHADED BOXES CONTAIN UPDATED REGIMENS. REGIMEN DOSING Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma—First-Line Treatment General treatment note: Routine use of growth factors is not recommended. Leukopenia is not a factor for treatment delay or dose reduction (except for escalated BEACOPP).1 CR=complete response IPS=International Prognostic Score PD=progressive disease PFTs=pulmonary function tests PR=partial response RT=radiation therapy SD=stable disease Stage IA, IIA Favorable ABVD (doxorubicin [Adriamycin] Days 1 and 15: Doxorubicin 25mg/m2 IV + bleomycin 10mg/m2 IV + vinblastine + bleomycin + vinblastine + 6mg/m2 IV + dacarbazine 375mg/m2 IV. dacarbazine [DTIC-Dome]) + Repeat cycle every 4 weeks for 2–4 cycles. involved-field radiotherapy (IFRT)1–4 Follow with IFRT after completion of chemotherapy. Abbreviated Stanford V Weeks 1, 3, 5 and 7: Vinblastine 6mg/m2 IV + doxorubicin 25mg/m2 IV. (doxorubicin + vinblastine + Weeks 1 and 5: Mechlorethamine 6mg/m2. -

Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Questions and Answers

Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Questions and Answers What is Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma? Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) is a cancer of the lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell. When lymphocytes become cancerous (malignant), they multiply and become tumors. Lymphocytes are normally found in the blood stream and lymph nodes. Lymph nodes are found throughout the body and are identified by their location. They are a part of the body’s immune system, which includes the lymphatic system, spleen and lymphocytes. Some lymph nodes can be found just by feeling them in the neck, groin or under the arms. Some cannot be felt, but they can be seen on X-rays. NHL is the fifth most common cancer in the United States. Men are at slightly higher risk than women. It is more common in adults than children. The average age at diagnosis is 45 to 55 years. The cause of NHL remains unknown. What Are the Types and Symptoms of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma? There are more than 30 different types of NHL. The specific types of NHL are associated with different symptoms. Low-grade or indolent NHL is usually associated with painless swelling of lymph nodes (usually in the neck or over the collarbone), but patients are otherwise healthy. The swelling may go away for a while, but then return. If the low-grade NHL has spread outside of the lymph nodes, such as to the stomach, there may be discomfort in the affected area. Low-grade lymphomas grow slowly. Examples of low-grade NHLs include: Marginal zone lymphomas. -

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Booklet

Understanding Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma A Guide for Patients, Survivors, and Loved Ones October 2017 Lymphoma Research Foundation (LRF) Helpline and Clinical Trials Information Service CONTACT THE LRF HELPLINE Trained staff are available to answer questions and provide support to patients, caregivers and healthcare professionals in any language. Our support services include: • Information on lymphoma, treatment options, side effect management and current research fi ndings • Financial assistance for eligible patients and referrals for additional fi nancial, legal and insurance help • Clinical trial searches based on patient’s diagnosis and treatment history • Support through LRF’s Lymphoma Support Network, a national one-to one volunteer patient peer program Monday through Friday, Toll-Free (800) 500-9976 or email [email protected] Understanding Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma A Guide For Patients, Survivors, and Loved Ones October 2017 This guide is an educational resource compiled by the Lymphoma Research Foundation to provide general information on adult non- Hodgkin lymphoma. Publication of this information is not intended to replace individualized medical care or the advice of a patient’s doctor. Patients are strongly encouraged to talk to their doctors for complete information on how their disease should be diagnosed, treated, and followed. Before starting treatment, patients should discuss the potential benefits and side effects of cancer therapies with their physician. Contact the Lymphoma Research Foundation Helpline: (800) 500-9976 [email protected] Website: www.lymphoma.org Email: [email protected] This patient guide is supported through unrestricted educational grants from: © 2017 Lymphoma Research Foundation. Information contained herein is the property of the Lymphoma Research Foundation (LRF). -

MINI-REVIEW Large Cell Lymphoma Complicating Persistent Polyclonal B

Leukemia (1998) 12, 1026–1030 1998 Stockton Press All rights reserved 0887-6924/98 $12.00 http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/leu MINI-REVIEW Large cell lymphoma complicating persistent polyclonal B cell lymphocytosis J Roy1, C Ryckman1, V Bernier2, R Whittom3 and R Delage1 1Division of Hematology, 2Department of Pathology, Saint Sacrement Hospital, 3Division of Hematology, CHUQ, Saint Franc¸ois d’Assise Hospital, Laval University, Quebec City, Canada Persistent polyclonal B cell lymphocytosis (PPBL) is a rare immunoglobulin (Ig) M with a polyclonal pattern on protein lymphoproliferative disorder of unclear natural history and its electropheresis. Flow cytometry cell analysis displays the pres- potential for B cell malignancy remains unknown. We describe the case of a 39-year-old female who presented with stage IV- ence of the CD19 antigen and surface IgM with a normal B large cell lymphoma 19 years after an initial diagnosis of kappa/lambda ratio. In contrast to CLL, CD5 is absent. There PPBL; her disease was rapidly fatal despite intensive chemo- is an association between HLA-DR 7 and PPBL in more than therapy and blood stem cell transplantation. Because we had two-thirds of the patients but the reason for such an associ- recently identified multiple bcl-2/lg gene rearrangements in ation remains unclear.3,6 There has been one report of PPBL blood mononuclear cells of patients with PPBL, we sought evi- occurring in identical female twins.7 No other obvious genetic dence of this oncogene in this particular patient: bcl-2/lg gene rearrangements were found in blood mononuclear cells but not predisposition or familial inheritance has yet been described in lymphoma cells. -

(Rituxan®), Rituximab-Abbs (Truxima®), Rituximab-Pvvr (Ruxience®) Prior Authorization Drug Coverage Policy

1 Rituximab Products: Rituximab (Rituxan®), Rituximab-abbs (Truxima®), Rituximab-pvvr (Ruxience®) Prior Authorization Drug Coverage Policy Effective Date: 2/1/2021 Revision Date: n/a Review Date: 7/2/20 Lines of Business: Commercial Policy type: Prior Authorization This Drug Coverage Policy provides parameters for the coverage of rituximab (Rituxan®), rituximab-abbs (Truxima®), and rituximab-pvvr (Ruxience®). Consideration of medically necessary indications are based upon U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indications, recommended uses within the Centers of Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) five recognized compendia, including the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Drugs & Biologics Compendium (Category 1 or 2A recommendations), and peer-reviewed scientific literature eligible for coverage according to the CMS, Medicare Benefit Policy Manual, Chapter 15, section 50.4.5 titled, “Off- Label Use of Anti-Cancer Drugs and Biologics.” This policy evaluates whether the drug therapy is proven to be effective based on published evidence-based medicine. Drug Description1-3 Rituximab (Rituxan®), rituximab-abbs (Truxima®), and rituximab-pvvr (Ruxience®) are monoclonal antibodies that target the CD20 antigen expressed on the surface of pre-B and mature B- lymphocytes. Upon binding to cluster of differentiation (CD) 20, rituximab mediates B-cell lysis. Possible mechanisms of cell lysis include complement dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) and antibody dependent cell mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC). B cells are believed to play a role in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and associated chronic synovitis. In this setting, B cells may be acting at multiple sites in the autoimmune/inflammatory process, including through production of rheumatoid factor (RF) and other autoantibodies, antigen presentation, T-cell activation, and/or proinflammatory cytokine production. -

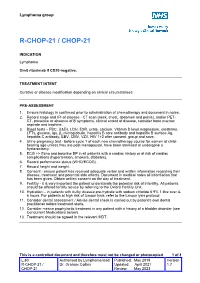

R-Chop-21 / Chop-21

Lymphoma group R-CHOP-21 / CHOP-21 INDICATION Lymphoma Omit rituximab if CD20-negative. TREATMENT INTENT Curative or disease modification depending on clinical circumstances PRE-ASSESSMENT 1. Ensure histology is confirmed prior to administration of chemotherapy and document in notes. 2. Record stage and IPI of disease - CT scan (neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis), and/or PET- CT, presence or absence of B symptoms, clinical extent of disease, consider bone marrow aspirate and trephine. 3. Blood tests – FBC, U&Es, LDH, ESR, urate, calcium, Vitamin D level,magnesium, creatinine, LFTs, glucose, Igs, β2 microglobulin, hepatitis B core antibody and hepatitis B surface Ag, hepatitis C antibody, EBV, CMV, VZV, HIV 1+2 after consent, group and save. 4. Urine pregnancy test • before cycle 1 of each new chemotherapy course for women of child- bearing age unless they are post-menopausal, have been sterilised or undergone a hysterectomy. 5. ECG +/- Echo and baseline BP in all patients with a cardiac history or at risk of cardiac complications (hypertension, smokers, diabetes). 6. Record performance status (WHO/ECOG). 7. Record height and weight. 8. Consent - ensure patient has received adequate verbal and written information regarding their disease, treatment and potential side effects. Document in medical notes all information that has been given. Obtain written consent on the day of treatment. 9. Fertility - it is very important the patient understands the potential risk of infertility. All patients should be offered fertility advice by referring to the Oxford Fertility Unit. 10. Hydration – in patients with bulky disease pre-hydrate with sodium chloride 0.9% 1 litre over 4- 6 hours. -

Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (ALCL)

Helpline (freephone) 0808 808 5555 [email protected] www.lymphoma-action.org.uk Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) This page is about anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL), a type of T-cell lymphoma. On this page What is ALCL? Who gets it? Symptoms Treatment Relapsed and refractory ALCL Research and targeted treatments We have separate information about the topics in bold font. Please get in touch if you’d like to request copies or if you would like further information about any aspect of lymphoma. Phone 0808 808 5555 or email [email protected]. What is ALCL? Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a type of T-cell lymphoma – a non-Hodgkin lymphoma that develops from white blood cells called T cells. Under a microscope, the cancerous cells in ALCL look large, undeveloped and very abnormal (‘anaplastic’). There are four main types of ALCL. They have complicated names based on their features and the types of proteins they make: • ALK-positive ALCL (also known as ALK+ ALCL) is the most common type. In ALK-positive ALCL, the abnormal T cells have a genetic change (mutation) that means they make a protein called ‘anaplastic lymphoma kinase’ (ALK). In other words, they test positive for ALK. ALK-positive ALCL is a fast-growing (high-grade) lymphoma. Page 1 of 6 © Lymphoma Action • ALK-negative ALCL (also known as ALK- ALCL) is a high-grade lymphoma that accounts for around 3 in every 10 cases of ALCL. The abnormal T cells do not make the ALK protein – they test negative for ALK. -

Download Product Insert (PDF)

Product Information Monomethyl Auristatin E Item No. 16267 CAS Registry No.: 474645-27-7 Formal Name: N-methyl-L-valyl-N-[(1S,2R)-4-[(2S)- 2-[(1R,2R)-3-[[(1R,2S)-2-hydroxy- H H N 1-methyl-2-phenylethyl]amino]-1- N methoxy-2-methyl-3-oxopropyl]-1- pyrrolidinyl]-2-methoxy-1-[(1S)-1- O H O methylpropyl]-4-oxobutyl]-N-methyl- N L-valinamide O Synonyms: Brentuximab vedotin, MMAE O O O MF: C39H67N5O7 N FW: N 718.0 H Purity: ≥95% H OH Stability: ≥2 years at -20°C Supplied as: A crystalline solid Laboratory Procedures For long term storage, we suggest that monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) be stored as supplied at -20°C. It should be stable for at least two years. MMAE is supplied as a crystalline solid. A stock solution may be made by dissolving the MMAE in the solvent of choice. MMAE is soluble in organic solvents such as ethanol, DMSO, and dimethyl formamide, which should be purged with an inert gas. The solubility of MMAE in these solvents is approximately 25, 5, and 20 mg/ml, respectively. Further dilutions of the stock solution into aqueous buffers or isotonic saline should be made prior to performing biological experiments. Ensure that the residual amount of organic solvent is insignificant, since organic solvents may have physiological effects at low concentrations. Organic solvent-free aqueous solutions of MMAE can be prepared by directly dissolving the crystalline solid in aqueous buffers. The solubility of MMAE in PBS, pH 7.2, is approximately 0.5 mg/ml. We do not recommend storing the aqueous solution for more than one day.