“It Doesn't Matter If You Are Disabled. You Are Talented”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

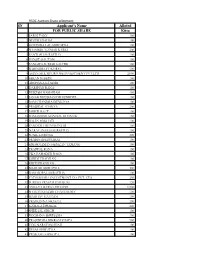

Applicant's Name Alloted for PUBLIC SHARE Kitta

RSDC Auction Share Allotment SN Applicant's Name Alloted FOR PUBLIC SHARE Kitta 1 SAROJ PANT 200 2 NITESH DAHAL 100 3 GOVINDA LAL SHRESTHA 100 4 SHAMBHU KUMAR KARKI 200 5 SANTOSH SHRESTHA 100 6 RANJIT GAUTAM 150 7 SANGITA SUBEDI KHATRI 100 8 RABINDRA POKHREL 100 9 ASIAN MULTIPURPOSE INVESTMENT PVT.LTD. 2,000 10 KIRAN SUBEDI 160 11 ARCHANA KUMARI 100 12 DARSHAN RANA 100 13 RUKESH MAHARJAN 450 14 JANAK BHUSHAN DHAUBHDEL 100 15 RAM CHANDRA DEVKOTA 100 16 PRAJJWAL SHAKYA 200 17 SMRITI RAUT 100 18 RAMASHISH MANDAL DHANUK 150 19 RAJAN BAKHATI 100 20 SANDESH DHAUBANJAR 100 21 NARAYAN DAS SHRESTHA 150 22 SUNIL GURUNG 300 23 PRABIN BHATTARAI 100 24 KRISHNAMAN HEMZAN TAMANG 100 25 PRAJWAL RANA 100 26 EKA BAHADUR RANA 100 27 SMRITI PRADHAN 100 28 KRITI PRADHAN 100 29 MAHESH SHRESTHA 300 30 RAM GOPAL SHRESTHA 100 31 PATHIBHARA INVESTMENT CO. PVT. LTD. 250 32 SURESH PRASAD PARAJULI 120 33 AMULYA RATNA STHAPIT 1,500 34 SHAKTI KUMARI CHAUDHARY 100 35 MADHAV GAUTAM 100 36 PRASSANNA SHAKYA 200 37 KAMALA DHAKAL 220 38 SHEETAL SINGH 100 39 ROCHANA SHRESTHA 200 40 PRASIDDHA BIKRAM THAPA 500 41 YOG NARAYAN SHAH 100 42 DIBAS SHRESTHA 100 43 PRAKASH SAPKOTA 100 44 BINU POUDEL THAPA 210 45 SHAKTI AMAR SINGH 250 46 NAWRAJ SIGDEL 150 47 KUL BAHADUR PANDIT 240 48 RAVINDRA ACHARYA 200 49 RAM MANOHAR SHRESTHA 100 50 BASANT KUMAR MISHRA 100 51 JOON SHRESTHA 200 52 PRATAP MAN SHRESTHA 500 53 DURGA BAHADUR BANIYA 1,500 54 GUHESWORI MERCHANT BANKING AND FINANCE 5,000 55 MUNA DEVI RAWAL 100 56 KUSUM SHRESTHA 100 57 CHHABILAL GYAWALI 550 58 YOGA RAJ JOSHI 100 59 NABINDRA -

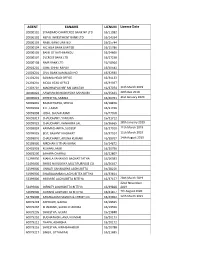

List of Active Agents

AGENT EANAME LICNUM License Date 20000101 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK NP LTD 16/11082 20000102 NEPAL INVESTMENT BANK LTD 16/14334 20000103 NABIL BANK LIMITED 16/15744 20000104 NIC ASIA BANK LIMITED 16/15786 20000105 BANK OF KATHMANDU 16/24666 20000107 EVEREST BANK LTD. 16/27238 20000108 NMB BANK LTD 16/18964 20901201 GIME CHHETRAPATI 16/30543 21001201 CIVIL BANK KAMALADI HO 16/32930 21101201 SANIMA HEAD OFFICE 16/34133 21201201 MEGA HEAD OFFICE 16/34037 21301201 MACHHAPUCHRE BALUWATAR 16/37074 11th March 2019 40000022 AAWHAN BAHUDAYSIYA SAHAKARI 16/35623 20th Dec 2019 40000023 SHRESTHA, SABINA 16/40761 31st January 2020 50099001 BAJRACHARYA, SHOVA 16/18876 50099003 K.C., LAXMI 16/21496 50099008 JOSHI, SHUVALAXMI 16/27058 50099017 CHAUDHARY, YAMUNA 16/31712 50099023 CHAUDHARY, KANHAIYA LAL 16/36665 28th January 2019 50099024 KARMACHARYA, SUDEEP 16/37010 11th March 2019 50099025 BIST, BASANTI KADAYAT 16/37014 11th March 2019 50099026 CHAUDHARY, ARUNA KUMARI 16/38767 14th August 2019 50199000 NIRDHAN UTTHAN BANK 16/14872 50401003 KISHAN LAMKI 16/20796 50601200 SAHARA CHARALI 16/22807 51299000 MAHILA SAHAYOGI BACHAT TATHA 16/26083 51499000 SHREE NAVODAYA MULTIPURPOSE CO 16/26497 51599000 UNNATI SAHAKARYA LAGHUBITTA 16/28216 51999000 SWABALAMBAN LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/33814 52399000 MIRMIRE LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/37157 28th March 2019 22nd November 52499000 INFINITY LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/39828 2019 52699000 GURANS LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/41877 7th August 2020 52799000 KANAKLAXMI SAVING & CREDIT CO. 16/43902 12th March 2021 60079203 ADHIKARI, GAJRAJ -

Improving Access to Justice Through Embracing a Legal Pluralistic Approach: a Case Study of Nepal

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 2017+ University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2018 Improving access to justice through embracing a legal pluralistic approach: a case study of Nepal Rajendra Ghimire University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses1 University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Ghimire, Rajendra, Improving access to justice through embracing a legal pluralistic approach: a case study of Nepal, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Law, University of Wollongong, 2018. -

Nepalese Translation Volume 1, September 2017 Nepalese Translation

Nepalese Translation Volume 1, September 2017 Nepalese Translation Volume 1,September2017 Volume cg'jfbs ;dfh g]kfn Society of Translators Nepal Nepalese Translation Volume 1 September 2017 Editors Basanta Thapa Bal Ram Adhikari Office bearers for 2016-2018 President Victor Pradhan Vice-president Bal Ram Adhikari General Secretary Bhim Narayan Regmi Secretary Prem Prasad Poudel Treasurer Karuna Nepal Member Shekhar Kharel Member Richa Sharma Member Bimal Khanal Member Sakun Kumar Joshi Immediate Past President Basanta Thapa Editors Basanta Thapa Bal Ram Adhikari Nepalese Translation is a journal published by Society of Translators Nepal (STN). STN publishes peer reviewed articles related to the scientific study on translation, especially from Nepal. The views expressed therein are not necessarily shared by the committee on publications. Published by: Society of Translators Nepal Kamalpokhari, Kathmandu Nepal Copies: 300 © Society of Translators Nepal ISSN: 2594-3200 Price: NC 250/- (Nepal) US$ 5/- EDITORIAL strategies the practitioners have followed to Translation is an everyday phenomenon in the overcome them. The authors are on the way to multilingual land of Nepal, where as many as 123 theorizing the practice. Nepali translation is languages are found to be in use. It is through desperately waiting for such articles so that translation, in its multifarious guises, that people diverse translation experiences can be adequately speaking different languages and their literatures theorized. The survey-based articles present a are connected. Historically, translation in general bird's eye view of translation tradition in the is as old as the Nepali language itself and older languages such as Nepali and Tamang. than its literature. -

Member Number Full Name Gender Membership Type M1718-195

Member Number Full Name Gender Membership Type M1718-195 Aakriti Dhakal Female General M1718-401 Aaradhana Devkota Nepal Female Student M1718-623 Aashika Upreti Ganywali Female Student M1718-499 Aashish Kandel Male Student M1718-498 Aashish Karki Male General M1718-482 Aayush Sapkota Male Student M1718-596 Abhinit Singh Male General M1718-241 ABINA GURUNG Female General M1718-274 Achyut Acharya Male General M1718-69 Adesh Sharma Male General M1718-130 Aditya Shrestha Male Student M1718-313 Akriti Chitrakar Female Student M1718-556 Akriti Ghimire Female General M1718-258 Aliz Karki Male Student M1718-307 Aliza Karki Female General M1718-20 Alok Kharel Male General M1718-296 Ambika Bhattarai Female General M1718-305 Ambika Sharma Female Student M1718-448 Ambika Tamang Female Student M1718-557 Ambika Adhikari Female General M1718-361 Ambika Bhusal adhikari Female Student M1718-18 Amit Parajuli Male General M1718-437 Amit Thapa Male Student M1718-275 Amita Shrestha Female General M1718-434 Amol Kattel Male Student M1718-618 Amrit Gyanwaly Male General M1718-24 Amrit Adhikari Male Student M1718-527 Amrita Gautam Female General M1718-370 Ananta Ghimire Female General M1718-555 Angir Babu Dahal Male General M1718-301 Angira Himadri Female Student M1718-34 Anil Basnet Male Current Team M1718-479 Anil Shrestha Male Student M1718-439 Anita Thapa Adhikari Female General M1718-229 Anita Pokharel Baskota Female General M1718-335 Anjan Paudel Male Student M1718-13 Anjana Pant Baral Female Current Team M1718-523 Anjana Poudel Female General M1718-174 -

Election-Result- 2021

Non-Resident Nepali Association National Coordination Council of USA National Election Commission (2021) Chief- Election Commissioner: Biswa N. Baral Election Commissioners: Bashu D. Phulara ESQ., Govinda K. Shrestha, Kul M. Acharya, Shiva R. Poudel Preliminary Result VOTE S.No CANDIDATE'S NAME POSITION RECEIVED POSITION Name President - National 1 Buddi S Subedi 5618 Winner 2 Dr Arjun Banjade 4148 3 Krishna P Lamichhane 5200 4 Tilak B KC 567 Name Senior Vice President - National 1 Babu Ram Lama 5563 2 Chitra Karki 2663 3 Krishna Jibi Pantha 6850 Winner Name Vice President - National 1 Ammar Bahadur Chhantyal 3126 2 Basudev Adhikari 4208 3 Bikash Upreti 4433 Winner 4 Chandra Lama 3369 5 Dilu Ram Parajuli 5097 Winner 6 Gopendra Raj Bhattrai 5496 Winner 7 Kishor Regmi 1065 8 Prabin KC 4049 9 Prakash Basnet 2358 10 Purna Chandra Baniya 2107 11 Ram Hari Adhikari 4296 12 Roshan Adhikari 1577 13 Suman Thapa 5975 Winner 14 Tank R Regmi 2147 Name Women Vice President - National 1 Diksha Basnet 8245 Winner 2 Kranti Aryal Bhandari 6466 Name General Secretary - National 1 Anjan Kumar Chaulagai 6312 Winner 2 Binod Bhatta 5145 3 Nabaraj Subedi 785 4 Nripendra Dhital 2509 Name Secretary (Open) - National 1 Anup Khanal 5957 Winner 2 Drona Gautam 5221 3 Narayan P Pokharel 3473 Name Secretary (Women) - National 1 Sunita Sapkota Kandel 7703 Winner 2 Tara Dhakal Marahatta 6872 Name Treasurer - National 1 Rajeev Prasad Shrestha 8808 Winner 2 Satendra Kumar Shah 5795 Name Joint Treasurer - National 1 Agni Prasad Dhakal 6206 Winner 2 Bikal Dhakal 4637 3 Rabindra -

539 4 - 10 February 2011 16 Pages Rs 30

#539 4 - 10 February 2011 16 pages Rs 30 Prime Minister-elect and UML Chairman Jhala Nath Khanal scored an improbable victory on Thursday MIN RATNA BAJRACHARYA ML Chairman Jhala Nath Khanal is now Uthe Prime Minister- elect, thanks to support from the Maoists in Thursdays election. He faces the multiple challenges of taking the MAN peace process forward while balancing the interests of the other parties, especially leaders within UML and the Maoists. OF THE MATCH 2 EDITORIAL 4 - 10 FEBRUARY 2011 #539 SLAP-HAPPY he media is better placed than most perceptive enough to recognise the public to predict what will happen next in anger against him and his ilk in the applause Tpolitics, but in Nepal this does not that slap generated? To go from red-faced to always apply. When politicians cannot be held abir-faced will not be enough to erase the accountable for what they say or do in private memory. He may be able to spin his ludicrous or public, anyone who claims to know what is position into one of necessity, but all we going on is on shaky ground indeed. can hear is this: I withdrew support for a With every turn of events in the ongoing majority government led by my own party, saga of the peace process, there has been and now I am ready to lead another majority cause for hope, cynicism or despair. The government. formal handover of PLA combatants to the The difference, of course, is that there will Special Committee a fortnight ago was one be many more hands reaching out to slap such milestone. -

Gaurishankar 2066 67

Gaurishankar List of UnPaid Divident Warrants Fiscal Year :67/68 S.NO. Holder No. Holder'S Name KITTA Net Amt W.No 1 81 JAGANNATH BHATTARAI 10 14.00 000081 2 82 YOGESH CHANDRA MISHRA 10 14.00 000082 3 83 NARESH PARIYAR 10 14.00 000083 4 84 VANDANA KUMARI MISHRA 10 14.00 000084 5 85 BIMALA NEPALI 10 14.00 000085 6 86 DIVAS NEPAL 10 14.00 000086 7 87 UTSAV NEPAL 10 14.00 000087 8 88 NIRMALA BASTOLA NEPAL 10 14.00 000088 9 89 BHARAT PD. NEPAL 10 14.00 000089 10 90 TILAK BDR. BHATTARAI 10 14.00 000090 11 91 GANGA BHATTARAI 10 14.00 000091 12 92 ROZINA KARKI 10 14.00 000092 13 97 LAXMAN PD. POKHREL 10 14.00 000097 14 98 KAMALA KUMARI KHANAL POKHREL 10 14.00 000098 15 99 ALINA POKHREL 10 14.00 000099 16 100 ABHISEK POKHREL 10 14.00 000100 17 101 YOG NRN. SAH 10 14.00 000101 18 102 PRABHA KUMARI MAHATO 10 14.00 000102 19 103 AMAN BIKRAM SHAH 10 14.00 000103 20 104 AYUSH BIKRAM SHAH 10 14.00 000104 21 105 SHILA KUMARI MAHATO 10 14.00 000105 22 137 SHARMILA KHADKA 10 14.00 000127 23 150 RAMESH KRISHNA MAHARJAN 10 14.00 000135 24 185 DHUNDIRAM KHANAL 10 14.00 000157 25 197 TULSI RAM KHANAL 10 14.00 000169 26 198 BHAGHABATA KHANAL 10 14.00 000170 27 199 MAHESH KHANAL 10 14.00 000171 28 200 SHEKHAR KHANAL 10 14.00 000172 29 207 NAWARAJ PURI 10 14.00 000179 30 208 UMESH PURI 10 14.00 000180 31 228 RAMESH LAGE 10 14.00 000198 32 229 TULSI PD NEPAL 10 14.00 000199 33 236 BIRAJ GAUTAM 10 14.00 000206 34 238 KANCHHI DAHAL 10 14.00 000208 35 239 RAM PD DAHAL 10 14.00 000209 36 262 SANJAY KUMAR PANDEY 10 14.00 000220 37 263 SAURAV PANDEY 10 14.00 000221 -

Curriculum Vitae

January, 2021 Curriculum Vitae Mahesh Jaishi Tarkeshwor-5, Kathmandu Date of birth: 2027-11-27 (1971-03-11) Mobile: 9851242042, Email: [email protected] [email protected] Academic qualification Degree Institute Division M. Sc. (Extension education) 2005 IAAS, Rampur, Chitwan, Nepal Distinction Major subjects in M. Sc.: Agricultural Extension and Rural Sociology Thesis: Impact of Rural-Urban Partnership Program (RUPP/UNDP) on Human Resource Development: A Case from Rupandehi district, Nepal. Job experiences: Position, duration and employer Job responsibilities Academic related experiences Assistant Professor • Teaching and guide undergraduates and post Agriculture Extension graduates for agriculture extension subject Department of social Science • Guide to student for Undergraduate Practicum Institute of Agriculture and Animal assessment (UPA) program as a partial fulfillment Science (IAAS), Lamjung Campus of course of B.Sc. (Ag.) • Guide Post graduate student for thesis research and February 2014 to till date documentation as a partial fulfillment Assistant Campus Chief • To assist and support the Campus Chief to execute, plan, monitor the overall academic and administrative activities of the Campus as per the vision, mission and goal of IAAS • Collaborate and liaison IAAS and Lamjung Campus for academic and administrative achievement • Act as a Chair of Annex program comittee of the campus Head of department (July2017-till) • Ensure, facilitate, monitor the teaching learning Department of Agri-economics Agri activities of B.Sc. -

Journal of Agriculture and Forestry University (JAFU) Volume 3 2019

Agriculture and Forestry University Rampur, Chitwan, Nepal Journal of Agriculture and Forestry University (JAFU) Volume 3 2019 Review Article 1. Agriculture land use in Nepal: Prospects and impacts on food security 1-9 R. H. Timilsina, G. P. Ojha, P. B. Nepali, and U. Tiwari Research Articles 1 Farmer’s perception on vulnerability of cropping pattern and adaptive mechanism in Panchthar and 11-23 Chitwan, Nepal D. Devkota, S. Dhakal, S. K. Khatri, and N. R. Devkota 2. Validating technical performance of micro-hydropower plants in Nepal 25-36 R. B. Thapa, B. R. Upreti, D. Devkota, and G. R. Pokharel 3. Fatty acid composition of oil extracted from soybean seeds harvested at different days of reproductive 37-42 stage K. H. Dhakal 4. Effects of different doses of nitrogen on jassid (Amrasca biguttula biguttula Ishida), and red cotton bug 43-48 (Dysdercus koenigii F) population and yield of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench) in Chitwan, Nepal B. Belbase, G. Neupane, H. Yadav, N. Pandey, and R. Regmi 5. Fruit bagging with cloth bag: An eco-friendly and cost effective management method of cucurbit’s 49-56 fruitfly (Bactocera cucurbiteae Coq.) on bitter gourd (Momordica charantia L.) in Kathmandu, Nepal S. Pokhrel 6. Variability, heritability and correlation studies on grain yield and related traits in spring wheat genotypes 57-62 B. R. Ojha, A. Ojha, and R. Chaudhary 7. Effects of foliar application of urea and micronutrients on yield and fruit quality of Mandarin 63-68 (Citrus reticulata Blanco) P. R. Rokaya, D. R. Baral, D. M. Gautam, A. K. -

Standard and Syllabus of Specialization Training

Standard and Syllabus of Specialization Training................. Office of the Attorney General, Nepal Government Attorney’s Specialization Standard, 2075 Preamble: Whereas, it is expedient to make provisions, for effective government representation and defense; Government Attorney had to have training of specialization, the Office of Attorney General has laid down this standard. 1. Short Title and Commencement: (1) This Standard may be called as “Government attorney Specialization Standard, 2075”. (2) This Standard shall come into force from 15 Jestha 2074. 2. Definition: In this Standard, unless the subject or the context means otherwise: - (a) “Government Attorney” means the Attorney General, Deputy Attorney General, Joint Attorney, Deputy Attorney, District Attorney, Deputy District Attorney, and the word shall also represent Gazetted officer of Government Attorney groups of Nepal Judicial Service. (b) “Specialized Government Attorney” means the government attorney who has gained a Standard determined special qualification, experience, and knowledge and has listed in section 8 of the standard. (c) “Management Committee” means the management committee of the Office of the Attorney General. (d) “Training provider Authority” means National Judicial Academy, Judicial Service Training Centre, Prosecution Training Centre and other National and Foreign institutions established according to the law which provide training on Law and Justice. 3. Government Attorney to be Specialized: (1) Government Attorney shall be specialized for the effective work performance of the Government Attorney. (2) While specialization of the government attorney according to the sub clause (1) the following specific area shall be considered: (a) Constitutional Law, (b) Organized Crime Prevention Law, (c) Banking and Commercial offence related Law, (d) Tax and Revenue Law, (e) Corruption Prevention Law, (f) Service related Law, (g) Government and Public Property Protection Law, (h) Cyber Crime Prevention Law, (i) Other Subjects as specified time to time by the Management Committee. -

Garima Bikas Bank Limited

GARIMA BIKAS BANK LIMITED BONUS TAX RECEIVABLE (FY 2073/74) BONUS TAX S.N BOID FULL NAME Amount 1 1301170000182670 KRISHNA ARYAL 51,500.25 2 1301170000013818 KRISHNA PRASAD PANGENI 45,900.00 3 1301150000056438 CHET NARAYAN SHRESTHA 27,386.10 4 1301140000007224 RUDRA BAHADUR B K 25,500.00 5 1301150000056480 RABINDRA KUNWAR 25,428.75 6 1301090000056541 BABU RAM DHAKAL 25,245.75 7 1301150000056476 OM BAHADUR THAPA 22,650.00 8 1301590000002589 GHAN SHYAM GAUNDEL 22,500.00 9 1301170000026390 AMRIT BANIYA 18,750.00 10 1301150000056398 TULASI RAM TIWARI 15,300.00 11 1301160000003116 SABIN SHRESTHA 15,300.00 12 1301370000797335 RAJESH SUBEDI 15,000.00 13 1301120000497532 DIWAKAR PAUDEL 12,240.00 14 1301120000029970 BINAY REGMI 11,250.00 15 1301120000482868 DHRUBA RAJ SUBEDI 10,710.00 16 1301100000286691 PADAM PANI KAFLE 8,972.25 17 1301150000056495 RAM CHANDRA GURUNG 8,100.00 18 1301010000010666 BHARAT RAJ DHAKAL 7,686.09 RADHADEVI PAUDEL BHANNE YUDDHA 1301150000047653 7,650.75 19 KUMARI MALLA 20 1301080000127921 DIPAK SHARMA 7,650.00 21 1301170000166745 THAHAR BAHADUR BHANDARI 7,500.00 22 1301090000418467 SANGITA UPADHYAYA 7,500.00 23 1301060000370553 PARBATI ARYAL PARU 7,500.00 24 1301100000339734 JAGANNATH PANGENI 7,500.00 25 1301060001052452 LOK PRASAD ARYAL 7,500.00 26 1301060000188081 RAJENDRA LIGAL 6,788.25 27 1301370000029897 PURUSHOTTAM PARAJULI 6,000.00 28 1301120000031935 YEK NARAYAN SHARMA 4,835.25 29 1301070000208131 LEKHNATH CHAPAGAIN 4,698.00 30 1301070000309358 KOPILDEV ADHIKARI 4,698.00 31 1301070000038093 BABU RAM ADHIKARI 4,590.75