Improving Access to Justice Through Embracing a Legal Pluralistic Approach: a Case Study of Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Crisis of Caste Renouncer: a Study of Dasnami Sanyasi Identity in Nepal

Molung Educational Frontier 91 Cultural Crisis of Caste Renouncer: A Study of Dasnami Sanyasi Identity in Nepal Madhu Giri* Abstract Jat NasodhanuJogikois a famous mocking proverb to denote the caste status of Sanyasi because the renouncer has given up traditional caste rituals set by socio-cultural institutions. In other cultural terms, being Sanyasi means having dissociation himself/herself with whatever caste career or caste-based social rank one might imagine. To explore the philosophical foundation of Sanyasi, they sacrificed caste rituals and fire (symbol of power, desire, and creation). By the virtues of sacrifice, Sanyasi set images of universalism, higher than caste order, and otherworldly being. Therefore, one should not ask the renouncer caste identity. Traditionally, Sanyasi lived in Akhada or Matha,and leadership, including ownership of the Matha transformed from Guru to Chela. On the contrary, DasnamiMahanta started marital and private life, which is paradoxical to the philosophy of Sanyasi.Very few of them are living in Matha,but the ownership of the property of Mathatransformed from father to son. The land and property of many Mathas transformed from religious Guthi to private property. In terms of cultural practices, DasnamiSanyasi adopted high caste culture and rituals in their everyday life. Old Muluki Ain 1854 ranked them under Tagadhari, although they did notassert twice-born caste in Nepal. Central Bureau of Statistics, including other government institutions of Nepal, listed Dasnamiunder the line ofChhetri and Thakuri. The main objective of the paper is to explore the transformation of Dasnami institutional characteristics and status from caste renunciation identity to caste rejoinder and from images of monasticism, celibacy, universalism, otherworldly orientation to marital, individualistic lay life. -

Country Poverty Analysis (Detailed) Nepal

Country Poverty Analysis (Detailed) Nepal Country Partnership Strategy: Nepal, 2013–20172013-2017 COUNTRY POVERTY ANALYSIS: NEPAL A. Background 1. This country poverty analysis draws mainly on the National Living Standards Surveys (NLSS), which was first conducted in 1996, and carried out again in 2004 and 2011. 1 The NLSS estimates the national poverty line following the cost of basic needs approach, which is the expenditure value in local currency required to fulfill both food and non food basic needs. The NLSS III findings can be disaggregated into fourteen analytical domains (mountains, urban- Kathmandu, urban-hill, urban-terai, eastern rural hills, rural central hills, rural western hills, rural mid- and far-western hills, rural eastern terai, rural central terai, rural western terai, and rural mid- and far-western terai. This analysis also draws from the Nepal Demographic Health Survey (2011) and the Census (2011) for information on health and access to basic services. B. Income Poverty and its Distribution 2. Using the national poverty line, poverty incidence has been falling at an accelerated pace from 41.8% to 30.9% between 1996 and 2004 and further to 25.2% of the overall population in 2011. This remarkable decline occurred in the backdrop of a significant increase in the national poverty line from NRs7,696 per capita per year in 2004 to NRs19,261 per capita per year in 2011 to account for a higher quality consumption pattern . 3. Using international poverty line of $1.25 per day, the incidence of poverty has declined steadily from 68.0% in 1996 to 53.1% in 2004 and 24.8% in 2011. -

Proceedings of International Conference on Climate Change Innovation and Resilience for Sustainable Livelihood 12-14 January 2015 Kathmandu, Nepal

Proceedings of International Conference on Climate Change Innovation and Resilience for Sustainable Livelihood 12-14 January 2015 Kathmandu, Nepal Organizers: The Small Earth Nepal (SEN) City University of New York (CUNY), USA Colorado State University (CSU), USA Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM), Government of Nepal Nepal Academy of Science and Technology (NAST), Nepal Agriculture and Forestry University (AFU), Nepal Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC), Nepal Editors: Dr. Soni Pradhananga, University of Rhode Island, USA Jeeban Panthi, The Small Earth Nepal, Nepal Dilli Bhattarai, The Small Earth Nepal Executive Summary Climate change is one of the most crucial environmental, social, and economic issues the world is facing today. Some impacts such as increasing heat stress, more intense floods, prolonged droughts, and rising sea levels have now become inevitable. Climatic extremes are becoming more frequent; wet periods are becoming wetter and dry periods are becoming dryer. People are able to describe the impacts faced by climate change but not the meaning of „climate change‟. The impacts are most severe for the poor countries. It is high time to plan and implement adaptive measures to minimize the adverse impacts due to climate change, and it is important to explore innovative ideas and practices in building resilience for sustainable development and livelihood, particularly in rural areas of developing countries which are highly vulnerable to climate change. Climate innovation and technologies involve basic science and engineering as well as information dissemination, capacity building, and community organizing. In this context an International Conference on Climate Change Innovation and resilience for Sustainable Livelihood was held in Kathmandu, Nepal from 12-14 January 2015. -

Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Diagnostic of Selected Sectors in Nepal

GENDER EQUALITY AND SOCIAL INCLUSION DIAGNOSTIC OF SELECTED SECTORS IN NEPAL OCTOBER 2020 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GENDER EQUALITY AND SOCIAL INCLUSION DIAGNOSTIC OF SELECTED SECTORS IN NEPAL OCTOBER 2020 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2020 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 8632 4444; Fax +63 2 8636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. Published in 2020. ISBN 978-92-9262-424-8 (print); 978-92-9262-425-5 (electronic); 978-92-9262-426-2 (ebook) Publication Stock No. TCS200291-2 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/TCS200291-2 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/. -

Four Ana and One Modem House: a Spatial Ethnography of Kathmandu's Urbanizing Periphery

I Four Ana and One Modem House: A Spatial Ethnography of Kathmandu's Urbanizing Periphery Andrew Stephen Nelson Denton, Texas M.A. University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, December 2004 B.A. Grinnell College, December 2000 A Disse11ation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology University of Virginia May 2013 II Table of Contents Introduction Chapter 1: An Intellectual Journey to the Urban Periphery 1 Part I: The Alienation of Farm Land 23 Chapter 2: From Newar Urbanism to Nepali Suburbanism: 27 A Social History of Kathmandu’s Sprawl Chapter 3: Jyāpu Farmers, Dalāl Land Pimps, and Housing Companies: 58 Land in a Time of Urbanization Part II: The Householder’s Burden 88 Chapter 4: Fixity within Mobility: 91 Relocating to the Urban Periphery and Beyond Chapter 5: American Apartments, Bihar Boxes, and a Neo-Newari 122 Renaissance: the Dual Logic of New Kathmandu Houses Part III: The Anxiety of Living amongst Strangers 167 Chapter 6: Becoming a ‘Social’ Neighbor: 171 Ethnicity and the Construction of the Moral Community Chapter 7: Searching for the State in the Urban Periphery: 202 The Local Politics of Public and Private Infrastructure Epilogue 229 Appendices 237 Bibliography 242 III Abstract This dissertation concerns the relationship between the rapid transformation of Kathmandu Valley’s urban periphery and the social relations of post-insurgency Nepal. Starting in the 1970s, and rapidly increasing since the 2000s, land outside of the Valley’s Newar cities has transformed from agricultural fields into a mixed development of planned and unplanned localities consisting of migrants from the hinterland and urbanites from the city center. -

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: a Newar Perspective

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: A Newar Perspective A Dissertation Submitted to the University of Tsukuba In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Public Policy Suwarn VAJRACHARYA 2014 To my mother, who taught me the value in a mother tongue and my father, who shared the virtue of empathy. ii Map-1: Original Nepal (Constituted of 12 districts) and Present Nepal iii Map-2: Nepal Mandala (Original Nepal demarcated by Mandalas) iv Map-3: Gorkha Nepal Expansion (1795-1816) v Map-4: Present Nepal by Ecological Zones (Mountain, Hill and Tarai zones) vi Map-5: Nepal by Language Families vii TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents viii List of Maps and Tables xiv Acknowledgements xv Acronyms and Abbreviations xix INTRODUCTION Research Objectives 1 Research Background 2 Research Questions 5 Research Methodology 5 Significance of the Study 6 Organization of Study 7 PART I NATIONALISM AND LANGUAGE POLITICS: VICTIMS OF HISTORY 10 CHAPTER ONE NEPAL: A REFLECTION OF UNITY IN DIVERSITY 1.1. Topography: A Unique Variety 11 1.2. Cultural Pluralism 13 1.3. Religiousness of People and the State 16 1.4. Linguistic Reality, ‘Official’ and ‘National’ Languages 17 CHAPTER TWO THE NEWAR: AN ACCOUNT OF AUTHORS & VICTIMS OF THEIR HISTORY 2.1. The Newar as Authors of their history 24 2.1.1. Definition of Nepal and Newar 25 2.1.2. Nepal Mandala and Nepal 27 Territory of Nepal Mandala 28 viii 2.1.3. The Newar as a Nation: Conglomeration of Diverse People 29 2.1.4. -

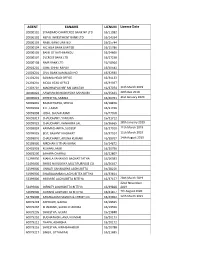

List of Active Agents

AGENT EANAME LICNUM License Date 20000101 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK NP LTD 16/11082 20000102 NEPAL INVESTMENT BANK LTD 16/14334 20000103 NABIL BANK LIMITED 16/15744 20000104 NIC ASIA BANK LIMITED 16/15786 20000105 BANK OF KATHMANDU 16/24666 20000107 EVEREST BANK LTD. 16/27238 20000108 NMB BANK LTD 16/18964 20901201 GIME CHHETRAPATI 16/30543 21001201 CIVIL BANK KAMALADI HO 16/32930 21101201 SANIMA HEAD OFFICE 16/34133 21201201 MEGA HEAD OFFICE 16/34037 21301201 MACHHAPUCHRE BALUWATAR 16/37074 11th March 2019 40000022 AAWHAN BAHUDAYSIYA SAHAKARI 16/35623 20th Dec 2019 40000023 SHRESTHA, SABINA 16/40761 31st January 2020 50099001 BAJRACHARYA, SHOVA 16/18876 50099003 K.C., LAXMI 16/21496 50099008 JOSHI, SHUVALAXMI 16/27058 50099017 CHAUDHARY, YAMUNA 16/31712 50099023 CHAUDHARY, KANHAIYA LAL 16/36665 28th January 2019 50099024 KARMACHARYA, SUDEEP 16/37010 11th March 2019 50099025 BIST, BASANTI KADAYAT 16/37014 11th March 2019 50099026 CHAUDHARY, ARUNA KUMARI 16/38767 14th August 2019 50199000 NIRDHAN UTTHAN BANK 16/14872 50401003 KISHAN LAMKI 16/20796 50601200 SAHARA CHARALI 16/22807 51299000 MAHILA SAHAYOGI BACHAT TATHA 16/26083 51499000 SHREE NAVODAYA MULTIPURPOSE CO 16/26497 51599000 UNNATI SAHAKARYA LAGHUBITTA 16/28216 51999000 SWABALAMBAN LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/33814 52399000 MIRMIRE LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/37157 28th March 2019 22nd November 52499000 INFINITY LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/39828 2019 52699000 GURANS LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/41877 7th August 2020 52799000 KANAKLAXMI SAVING & CREDIT CO. 16/43902 12th March 2021 60079203 ADHIKARI, GAJRAJ -

DAHAL-THESIS-2019.Pdf (8.716Mb)

Copyright By Asmita Dahal 2019 The Thesis Committee for Asmita Dahal Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Thesis: An investigation on Vernacular Architecture of Marpha, Mustang, Nepal and understanding the influences and changes in architecture and its sustainability APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Juliana Felkner, Supervisor Michael Garrison An investigation on Vernacular Architecture of Marpha, Mustang, Nepal and understanding the influences and changes in architecture and its sustainability by Asmita Dahal Thesis Presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements For the degree of Master of Science in Sustainable Design The University of Texas at Austin August 2019 Dedication I would like to dedicate this to the high mountains, tilted trees and scary roads of Mustang, Nepal where the beautiful and kind soul lives in simplicity and ground to earth. And of course, to my parents, my brothers and my friends who made it easy when the times were hard. Acknowledgment I would like to thank, my supervisor Juliana Felkner and Michael Garrison who supported me for this research and helped me in all possible ways. They guided me to give proper shape to my thesis and I am grateful towards them. I am grateful to my family. Despite being born as a girl in an underdeveloped country, they gave me courage and blessing to travel 8000 miles away from home alone to make my dream a reality. I am thankful towards all those kind and helpful souls, who came as a friend in my life to handle my panics and drama. -

Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal

UNEQUAL CITIZENS UNEQUAL37966 Public Disclosure Authorized CITIZENS Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal Caste and Ethnic Exclusion Gender, THE Department For International WORLD DFID Development SUMMARY BANK The World Bank DFID Nepal Nepal Office P.O. Box 106 P.O. Box 798 Kathmandu, Nepal Yak and Yeti Hotel Tel.: 5542980 Complex Fax: 5542979 Durbar Marg Public Disclosure Authorized Kathmandu, Nepal Tel.: 4226792, 4226793 E-mail Fax: 4225112 [email protected] Websites www.worldbank.org.np, Website www.bishwabank.org.np www.dfid.gov.uk Public Disclosure Authorized DFID Development International Department For ISBN 99946-890-0-2 9 799994 689001 > BANK WORLD THE Public Disclosure Authorized A Kathmandu businessman gets his shoes shined by a Sarki. The Sarkis belong to the leatherworker subcaste of Nepal’s Dalit or “low caste” community. Although caste distinctions and the age-old practices of “untouchability” are less rigid in urban areas, the deeply entrenched caste hierarchy still limits the life chances of the 13 percent of Nepal’s population who belong to the Dalit caste group. UNEQUAL CITIZENS Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal SUMMARY THE Department For International WORLD DFID Development BANK THE Department For International WORLD DFID Development BANK The World Bank DFID Nepal Nepal Office P.O. Box 106 P.O. Box 798 Kathmandu, Nepal Yak and Yeti Hotel Complex Tel.: 5542980 Durbar Marg Fax: 5542979 Kathmandu, Nepal Tel.: 4226792, 4226793 E-mail Fax: 4225112 [email protected] Websites www.worldbank.org.np, Website www.bishwabank.org.np www.dfid.gov.uk A copublication of The World Bank and the Department For International Development, U.K. -

To Download the Presentation Slides

5/15/2014 Development Orthodoxy: Persistent policy failure in the Himalayas Netra Chhetri Consortium for Science, Policy and Outcomes Arizona State University 5/15/2014 Fast Facts 27.47 millions population (25.2% living below poverty) Ranked 157th out of 187 countries (HDR, 2013) High juvenile malnutrition (47% under 5 are stunted and 36% underweight) 1/3rd of working age male population migrate for work Agriculture is one of the largest contributors to national GDP (36%) Netra Chhetri, Arizona State University 1 5/15/2014 1 5/15/2014 …investment in agricultural development is crucial Netra Chhetri, Arizona State University 2 5/15/2014 ….struggle for agricultural development continues in mythical Shangri-La Netra Chhetri, Arizona State University 3 5/15/2014 2 5/15/2014 Netra Chhetri, Arizona State University 4 5/15/2014 Courtesy: M. Shrestha One of the unique features of Nepal’s agriculture is its close coupling among crop, forest, rangeland & other common resources Courtesy: M. Shrestha Netra Chhetri, Arizona State University 5 5/15/2014 3 5/15/2014 Courtesy: M. Shrestha Netra Chhetri, Arizona State University 6 5/15/2014 Forms of agricultural development Bottom-up Top-down Generating income Managing risk Building capacity Confronting Livelihoods Large scale NetraClumsy Chhetri, Arizona State University 7 5/15/2014Elegant 4 5/15/2014 Forms of engagement Social mobilization Participatory Top-down Bilateral Small scale Large scale Netra Chhetri, Arizona State University 8 5/15/2014 Economic development activities Small and diverse Specific -

Exclusionary Policies and Practices in Chinese Minority Education: the Case of Tibetan Education

Exclusionary Policies and Practices in Chinese Minority Education: The Case of Tibetan Education Bonnie Johnson Pennsylvania State University Nalini Chhetri Pennsylvania State University Introduction Multicultural countries around the world have implemented mass education for school- aged children. Educational systems exist to reproduce the dominant society in which they are an integral part or to impose a new social order. "Transmitting culture and socializing youth are basic goals of the public school" (Gabjrcia, 1978, p.8). Another goal of public education is to promote national unity and economic development. However, the development of mass education in multicultural societies has often been at the expense of minority culture and ethnic identity. Schools are often the medium through which the state establishes the culture of the dominant language while at the same time depriving linguistic minority children of their right to use their mother tongue. Minority education policy is fraught with political, educational, economic and social complexities. This paper examines how the government of the People's Republic of China (hereafter referred to as China) modifies its educational policies to achieve separate and distinct regional objectives, which are linked to regional and ethnic differences. These policies often result in exclusionary practices. Using the case of the Chinese region of Tibet, this paper illustrates the dichotomy of Chinese educational policy: how to achieve universal education for all students and at the same time contain regional ethnic resistance against the communist government and maintain national unity. Education in China China is a country of 56 "official nationalities." Out of a population of 1.2 billion people, over 70 million are non-Han Chinese (Insight Guide, 1998). -

Fatalism And

* e FATALISM AND *. ., 4 . 1 \ MODERNIZATION f~!???>$+, .7xp.SL. + psi +--. c-% :-+$,;.+. 6. d td f*&$ < Wz'5..*ak lib It attempts to' diagnose4 Nepal's ills throukh the eye&of a 'sympathetic yet critic'al I insider. It 'has something of the flavo,ur-of , -4 #. other such attempts: 'Re Tocqueville~s . ~ncienRegime, Weber's Protestant . Ethic, Taine's ~oteiUpon England. P It .,,is worth considering at some length 4,--,yf2* , a,.- Ld , i. because of its insights and because a% Bista, a$-<anM~-~..*~Finsidq. , ll,.x , canc say things wdich i :,;a;:&h&:*%y2*t. t-i:+ - i no outslQr could'say .-Alan ~acfirlane k 8 in Cambridge Anthropolqgy. e C % g DOR BAHADUR BISTA i _r $: f > 8.$7 -, *, 9. p: I continued from front jlap should be scrutinized and their negative A bold and incisive analysis of Nepal's elements purged before they are adopted. society, and its attempts to develop and Nepal's future hope lies in its ethnic cultures respond to change, from someone who is whose simplicity provides a greater both an insider and an outsider to Nepal. At flexibility and thus a greater propensity to an early age Dor Bahadur Bista travelled all development and change, than the over Nepal in the company of the leading cumbersome and ossified structure of the anthropologist Christoph von urbane upper class, and caste, society of the Furer-Haimendor f which helped him to Kathmandu Valley. acquire an insight that enables him to make an objective and frank comment on his country . Born in 1928 in Lalitpur, Nepal, Dor Bahadur Bista was educated at Kathmandu, Nepal has a heteronomous society with a London and Wisconsin, and is now complex ethnic mix.