How Does Social Protection Contribute to Social Inclusion in Nepal?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Crisis of Caste Renouncer: a Study of Dasnami Sanyasi Identity in Nepal

Molung Educational Frontier 91 Cultural Crisis of Caste Renouncer: A Study of Dasnami Sanyasi Identity in Nepal Madhu Giri* Abstract Jat NasodhanuJogikois a famous mocking proverb to denote the caste status of Sanyasi because the renouncer has given up traditional caste rituals set by socio-cultural institutions. In other cultural terms, being Sanyasi means having dissociation himself/herself with whatever caste career or caste-based social rank one might imagine. To explore the philosophical foundation of Sanyasi, they sacrificed caste rituals and fire (symbol of power, desire, and creation). By the virtues of sacrifice, Sanyasi set images of universalism, higher than caste order, and otherworldly being. Therefore, one should not ask the renouncer caste identity. Traditionally, Sanyasi lived in Akhada or Matha,and leadership, including ownership of the Matha transformed from Guru to Chela. On the contrary, DasnamiMahanta started marital and private life, which is paradoxical to the philosophy of Sanyasi.Very few of them are living in Matha,but the ownership of the property of Mathatransformed from father to son. The land and property of many Mathas transformed from religious Guthi to private property. In terms of cultural practices, DasnamiSanyasi adopted high caste culture and rituals in their everyday life. Old Muluki Ain 1854 ranked them under Tagadhari, although they did notassert twice-born caste in Nepal. Central Bureau of Statistics, including other government institutions of Nepal, listed Dasnamiunder the line ofChhetri and Thakuri. The main objective of the paper is to explore the transformation of Dasnami institutional characteristics and status from caste renunciation identity to caste rejoinder and from images of monasticism, celibacy, universalism, otherworldly orientation to marital, individualistic lay life. -

Country Poverty Analysis (Detailed) Nepal

Country Poverty Analysis (Detailed) Nepal Country Partnership Strategy: Nepal, 2013–20172013-2017 COUNTRY POVERTY ANALYSIS: NEPAL A. Background 1. This country poverty analysis draws mainly on the National Living Standards Surveys (NLSS), which was first conducted in 1996, and carried out again in 2004 and 2011. 1 The NLSS estimates the national poverty line following the cost of basic needs approach, which is the expenditure value in local currency required to fulfill both food and non food basic needs. The NLSS III findings can be disaggregated into fourteen analytical domains (mountains, urban- Kathmandu, urban-hill, urban-terai, eastern rural hills, rural central hills, rural western hills, rural mid- and far-western hills, rural eastern terai, rural central terai, rural western terai, and rural mid- and far-western terai. This analysis also draws from the Nepal Demographic Health Survey (2011) and the Census (2011) for information on health and access to basic services. B. Income Poverty and its Distribution 2. Using the national poverty line, poverty incidence has been falling at an accelerated pace from 41.8% to 30.9% between 1996 and 2004 and further to 25.2% of the overall population in 2011. This remarkable decline occurred in the backdrop of a significant increase in the national poverty line from NRs7,696 per capita per year in 2004 to NRs19,261 per capita per year in 2011 to account for a higher quality consumption pattern . 3. Using international poverty line of $1.25 per day, the incidence of poverty has declined steadily from 68.0% in 1996 to 53.1% in 2004 and 24.8% in 2011. -

Appraisal of the Karnali Employment Programme As a Regional Social Protection Scheme

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aston Publications Explorer Appraisal of the Karnali Employment Programme as a regional social protection scheme Kirit Vaidya in collaboration with Punya Prasad Regmi & Bhesh Ghimire for Ministry of Local Development, Government of Nepal & ILO Office in Nepal November 2010 Copyright © International Labour Organization 2010 First published 2010 Publications of the International Labour Offi ce enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authoriza- tion, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Offi ce, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Offi ce welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with reproduction rights organizations may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to fi nd the reproduction rights organization in your country. social protection / decent work / poverty alleviation / public works / economic and social development / Nepal 978-92-2-124017-4 (print) 978-92-2-124018-1 (web pdf) ILO Cataloguing in Publication Data The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Offi ce of the opinions expressed in them. Reference to names of fi rms and commercial products and processes does not imply their endorsement by the International Labour Offi ce, and any failure to mention a particular fi rm, commercial product or process is not a sign of disapproval. -

Proceedings of International Conference on Climate Change Innovation and Resilience for Sustainable Livelihood 12-14 January 2015 Kathmandu, Nepal

Proceedings of International Conference on Climate Change Innovation and Resilience for Sustainable Livelihood 12-14 January 2015 Kathmandu, Nepal Organizers: The Small Earth Nepal (SEN) City University of New York (CUNY), USA Colorado State University (CSU), USA Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM), Government of Nepal Nepal Academy of Science and Technology (NAST), Nepal Agriculture and Forestry University (AFU), Nepal Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC), Nepal Editors: Dr. Soni Pradhananga, University of Rhode Island, USA Jeeban Panthi, The Small Earth Nepal, Nepal Dilli Bhattarai, The Small Earth Nepal Executive Summary Climate change is one of the most crucial environmental, social, and economic issues the world is facing today. Some impacts such as increasing heat stress, more intense floods, prolonged droughts, and rising sea levels have now become inevitable. Climatic extremes are becoming more frequent; wet periods are becoming wetter and dry periods are becoming dryer. People are able to describe the impacts faced by climate change but not the meaning of „climate change‟. The impacts are most severe for the poor countries. It is high time to plan and implement adaptive measures to minimize the adverse impacts due to climate change, and it is important to explore innovative ideas and practices in building resilience for sustainable development and livelihood, particularly in rural areas of developing countries which are highly vulnerable to climate change. Climate innovation and technologies involve basic science and engineering as well as information dissemination, capacity building, and community organizing. In this context an International Conference on Climate Change Innovation and resilience for Sustainable Livelihood was held in Kathmandu, Nepal from 12-14 January 2015. -

Feasibility Study of Kailash Sacred Landscape

Kailash Sacred Landscape Conservation Initiative Feasability Assessment Report - Nepal Central Department of Botany Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Nepal June 2010 Contributors, Advisors, Consultants Core group contributors • Chaudhary, Ram P., Professor, Central Department of Botany, Tribhuvan University; National Coordinator, KSLCI-Nepal • Shrestha, Krishna K., Head, Central Department of Botany • Jha, Pramod K., Professor, Central Department of Botany • Bhatta, Kuber P., Consultant, Kailash Sacred Landscape Project, Nepal Contributors • Acharya, M., Department of Forest, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation (MFSC) • Bajracharya, B., International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) • Basnet, G., Independent Consultant, Environmental Anthropologist • Basnet, T., Tribhuvan University • Belbase, N., Legal expert • Bhatta, S., Department of National Park and Wildlife Conservation • Bhusal, Y. R. Secretary, Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Das, A. N., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Ghimire, S. K., Tribhuvan University • Joshi, S. P., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Khanal, S., Independent Contributor • Maharjan, R., Department of Forest • Paudel, K. C., Department of Plant Resources • Rajbhandari, K.R., Expert, Plant Biodiversity • Rimal, S., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Sah, R.N., Department of Forest • Sharma, K., Department of Hydrology • Shrestha, S. M., Department of Forest • Siwakoti, M., Tribhuvan University • Upadhyaya, M.P., National Agricultural Research Council -

Studies on the Most Traded Medicinal Plants from the Dolpa District of Nepal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Toyama Repository STUDIES ON THE MOST TRADED MEDICINAL PLANTS FROM THE DOLPA DISTRICT OF NEPAL Mohan B. Gewali Division of Visiting Professors Institute of Natural Medicine University of Toyama Abstract The traditional uses, major chemical constituents and prominent biological activities of the most traded medicinal plants from Dolpa district of Nepal are described in this article. Cradled on the laps of the central Himalayan range, Nepal (147,181 Km2) is sandwiched between two Asian giants, India on the South and China on the North. Nepal is divided into 14 zones and 75 districts. The Karnali zone, which has a border with Tibet region of China, is made up of five districts. Dolpa district (7,889 km²) is one of them. Dolpa district’s topography starts from the subtropical region (1575 meter) and ends in the nival region (6883 meter) in the trans-Himalayan region. The district has a population of about 29545 with Hindu 60%, Buddhist 40% including 5.5% ancient Bonpo Religion. Major ethnic groups/castes belonging to both Hindu and Buddhist religions include Kshetri, Dangi, Rokaya, Shahi, Buda, Thakuri, Thakulla, Brahmins, Karki, Shrestha, Sherpa and other people of Tibetan origin. The languages spoken are Nepali, Dolpo and Kaike. Dolpo is a variant of the Tibetan language. Kaike is considered indigenous language of Tichurong valley. In the Dolpa district, the traditional Tibetan medical practices are common. The traditional Tibetan practitioners called the Amchis provide the health care service. The Amchis have profound knowledge about the medicinal herbs and the associated healing properties of the medicinal plants found in the Dolpa district. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Tila Karnali Watershed Profile: Status, Challenges and Opportunities for Improved Water Resource Management

Cover photo: A view of the confluence of the Tila Karnali and the Humla Karnali rivers in the Tila- Karnali Watershed, Kalikot. Photo credit: USAID Paani Program II TILA KARNALI WATERSHED PROFILE: STATUS, CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR IMPROVED WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT Program Title: USAID Paani Program DAI Project Number: 1002810 Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Nepal IDIQ Number: AID-OAA-I-14-00014 Task Order Number: AID-367-TO-16-00001 Contractor: DAI Global LLC Date of Publication: March 28, 2019 The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. III Table of Contents TABLES ....................................................................................................................... VI FIGURES ................................................................................................................... VIII ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................................... IX ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................ 2 1. TILA KARNALI WATERSHED: NATURE, WEALTH AND POWER ..... 10 2. NATURE........................................................................................................... 11 2.1. TILA KARNALI WATERSHED ............................................................................... -

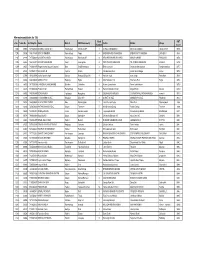

PMT Result 2075 List.Xlsx

Alternate candidates for TSLC Ward PMT S. No. Token No SLC Reg No Name District VDC/Municipality Father Mother Village Number Score 1205 29868 7477022010 BHARAT RAJ BHATT Kanchanpur Bhimdatta NP 8 SHREE NAND BHATT MOTI DEVI BHATT TILACHOUR 997.6 1206 30396 1807718001 BINUTA KHADKA Ramechhap Farpu 4 BADRI BAHADUR KHADKA BISHNU MAYA KHADKA LACHEPU 997.6 1207 32226 7277059022 SUSMITA CHAND Kanchanpur Bhimdatta NP 6 KESHAB BAHADUR CHAND MANJU CHAND BANGAUN 997.6 1208 34943 7441233012 SUSMITA ADHIKARI Kaski Lwangghale 4 TEK PRASAD ADHIKARI TIL KUMARI ADHIKARI KOLELI 997.6 1209 30035 7436031070 Ragani kumari jayswal Jayswal Bara GanjBhawanipur 3 Bhairo parsad Shambha devi jayswal Ganjbhawanipur 997.7 1210 32691 7457005127 SUJATA G M Pyuthan Khaira 2 Nim Bahadur G m Laxmi Gharti Magar Palasi 997.8 1211 32804 7010176010 aasha kumari singh Sunsari RamganjBelgachhi 8 hariram singh nanu singh Ramdhuni 997.8 1212 33666 6946100001 ANDIKA PUN Baglung Righa 6 Man Bahadur Pun Tilachana Pun Righa 997.8 1213 34050 7417059004 CHANDIKA LAMICHHANE Dolakha Chilankha 8 Kumar Lamichhane Rama Lamichhane 997.8 1214 32273 7418082005 Prabin Khatri Ramechhap Deurali 6 Ganesh Bahadur Khatri Maiya Khatri Deurali 997.9 1215 33092 7401013060 SONI MADEN Taplejung Hangdeva 9 SILBAHADUR MADEN SITAMAYA PALUNGWA MADEN eseratol 997.9 1216 33391 7225022009 CHHOISANG GHALE Nuwakot Bidur N.P. 8 SHAKTI GHALE MANMAYA GHALE RAISING 997.9 1217 28738 7436099042 AJAY KUMAR YADAV Bara Madhurijabdi 7 Jhoti Prasad Yadav Mina Devi Madhurijabdi 998 1218 30814 7456070039 PATHA BAHADUR D.C. -

Krishna Bahadur Shahi

CV-Krishna Krishna Bahadur Shahi Born: 29 May 1983 Address: Tilagupha Municipality-6, Kalikot, Nepal Contact No.: Mobile: 9848305151/9858320505 Email: [email protected]/[email protected] Academic Qualifications: 2014 M. A. in Sociology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Science, Birendranagar Multiple Campus Surkhet (T.U.) 2005 Bachelor in Education, Education Campus Surkhet (T.U.) 2002 Intermediate (+2) in Education, Birendranagar Multiple Campus, Surkhet (HSEB) 2000 S.L.C., Satya Devi H.S. School Jubitha, Kalikot Major Trainings Received: 2nd to 11th Sep. 2006 Professional Report Writing and Proposal Writing by SNV/Nepal 13th to 19th Oct. 2006 Social Mobilization TOT by PAF, Nepal 2008 Start and Improve Your Business SIYB-Level-1 International Labor Organization (ILO)s Two week Training of Trainers' Program by MEDEP, Nepal 21st to 23rd Feb. 2009 Institutional Development (TOT) by PAF, Nepal 25th June to 9th July 2009 Development of Trainers (DOT) by UNICEF/VDRC, Nepal 23rd Aug. to 2nd Sep. 2009 Professional Arc GIS Training by Sea Gate Company, Lalitpur 15th to 22nd Sep. 2009 Tourism Based Micro-Enterprises Development Training by MEDEP, Nepal 11th to 15th Nov. 2009 Transparency, Accountability and Good Governance by SNV/nepal 28th Nov. to 2nd Dec. 2009 Appreciate Inquiry Training by PAF, Nepal 29th Aug. to 2nd Sep. 2013 Value Chain Based GESI (TOT) by HVAP, Surkhet 25th Oct. to 1st Nov. 2013 Cooperative Development, Procurement System and Business Plan Preparation Training by PCU/WUPAP 30th May to 3rd June 2014 Participatory Monitoring, -

Dolpa Juphal Airport

DOLPA JUPHAL AIRPORT Brief Description Dolpa (Juphal) Airport is situated at Juphal Municipality of Dolpa District, Karnali Province. The airport serves as the gate way to Shey- Phoksundo National Park where the Phoksundo Lake is the major attraction. The airport also serves for the means of connection to upper Dolpa Trek which is one of the famous destinations for tourists. General Information Name DOLPA Location Indicator VNDP IATA Code DOP Aerodrome Reference Code 1B Aerodrome Reference Point 285909 N/0824909 E Province/District Karnali/Dolpa Distance and Direction from City Three hours walking Distance from District Headquater( Dunai) Elevation 2503 m. /8212 ft. Off: 977-87690429 Tower: 977-87690429 Contact AFS: VNDPYDYX E-mail: [email protected] 16th Feb to 15th Nov 0600LT-1215LT Operation Hours 16th Nov to 15th Feb 0630LT-1215LT Status Operational Year of Start of Operation 1975 Serviceability All Weather Land Approx. 59659.09 m2 Re-fueling Facility Not Available Service AFIS Type of Traffic Permitted Visual Flight Rule (VFR) Type of Aircraft DHC6, L410, Y12 Schedule Operating Airlines Tara Air, Sita Air, Nepal Airlines, Summit Air Schedule Connectivity Nepalgunj, Surkhet RFF Not Available Infrastructure Condition Airside Runway Type of Surface Bituminous Paved (Asphalt Concrete) Runway Dimension 560 m x 20 m Runway Designation 16/34 Parking Capacity Two DHC6 Types Size of Apron 2400 sq.m. Apron Type Asphalt Concrete Airport Facilities Console One Man Position Tower Console with Associated Equipment and Accessories Communication, -

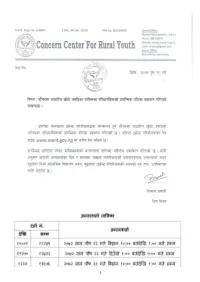

VBST Short List

1 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10002 2632 SUMAN BHATTARAI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. KEDAR PRASAD BHATTARAI 136880 10003 28733 KABIN PRAJAPATI BHAKTAPUR BHAKTAPUR N.P. SITA RAM PRAJAPATI 136882 10008 271060/7240/5583 SUDESH MANANDHAR KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. SHREE KRISHNA MANANDHAR 136890 10011 9135 SAMERRR NAKARMI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. BASANTA KUMAR NAKARMI 136943 10014 407/11592 NANI MAYA BASNET DOLAKHA BHIMESWOR N.P. SHREE YAGA BAHADUR BASNET136951 10015 62032/450 USHA ADHIJARI KAVRE PANCHKHAL BHOLA NATH ADHIKARI 136952 10017 411001/71853 MANASH THAPA GULMI TAMGHAS KASHER BAHADUR THAPA 136954 10018 44874 RAJ KUMAR LAMICHHANE PARBAT TILAHAR KRISHNA BAHADUR LAMICHHANE136957 10021 711034/173 KESHAB RAJ BHATTA BAJHANG BANJH JANAK LAL BHATTA 136964 10023 1581 MANDEEP SHRESTHA SIRAHA SIRAHA N.P. KUMAR MAN SHRESTHA 136969 2 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10024 283027/3 SHREE KRISHNA GHARTI LALITPUR GODAWARI DURGA BAHADUR GHARTI 136971 10025 60-01-71-00189 CHANDRA KAMI JUMLA PATARASI JAYA LAL KAMI 136974 10026 151086/205 PRABIN YADAV DHANUSHA MARCHAIJHITAKAIYA JAYA NARAYAN YADAV 136976 10030 1012/81328 SABINA NAGARKOTI KATHMANDU DAANCHHI HARI KRISHNA NAGARKOTI 136984 10032 1039/16713 BIRENDRA PRASAD GUPTABARA KARAIYA SAMBHU SHA KANU 136988 10033 28-01-71-05846 SURESH JOSHI LALITPUR LALITPUR U.M.N.P. RAJU JOSHI 136990 10034 331071/6889 BIJAYA PRASAD YADAV BARA RAUWAHI RAM YAKWAL PRASAD YADAV 136993 10036 071024/932 DIPENDRA BHUJEL DHANKUTA TANKHUWA LOCHAN BAHADUR BHUJEL 136996 10037 28-01-067-01720 SABIN K.C.