AREA Thesis Statements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

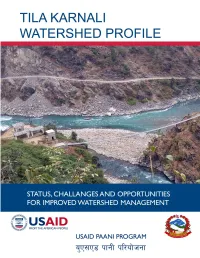

Tila Karnali Watershed Profile: Status, Challenges and Opportunities for Improved Water Resource Management

Cover photo: A view of the confluence of the Tila Karnali and the Humla Karnali rivers in the Tila- Karnali Watershed, Kalikot. Photo credit: USAID Paani Program II TILA KARNALI WATERSHED PROFILE: STATUS, CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR IMPROVED WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT Program Title: USAID Paani Program DAI Project Number: 1002810 Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Nepal IDIQ Number: AID-OAA-I-14-00014 Task Order Number: AID-367-TO-16-00001 Contractor: DAI Global LLC Date of Publication: March 28, 2019 The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. III Table of Contents TABLES ....................................................................................................................... VI FIGURES ................................................................................................................... VIII ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................................... IX ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................ 2 1. TILA KARNALI WATERSHED: NATURE, WEALTH AND POWER ..... 10 2. NATURE........................................................................................................... 11 2.1. TILA KARNALI WATERSHED ............................................................................... -

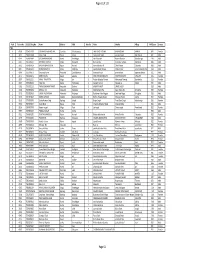

TSLC PMT Result

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal -

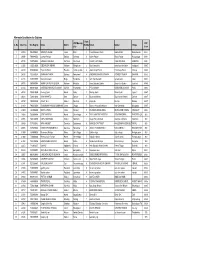

PMT Result 2075 List.Xlsx

Alternate Candidates for Diploma Ward VDC/Municip PMT S. No. Token No SLC Reg No Name District Numbe Father Mother Village ality Score r 1 29169 7063002034 NIRMAYA SHAHI Jumla Birat 3 Prem Bahadur Shahi Kabita Shahi Barkotebada 968.1 2 30698 7468080053 Laxman Pariyar Bardiya Sorhawa 9 Kuber Pariyar Bhula Pariyar Puspanagar 968.1 3 30798 7374036042 RAMESH BOHARA Darchula Sharmauli 1 HARDEV BOHARA HIRA BOHARA SARMOLI 968.1 4 33026 7100271008 SIDDHA DHUNGANA Achham Mangalsen 5 Moti Ram jaishi manshara devi jaishi kudabasti 968.2 5 33372 6724003049 Rajendra Bulun Rasuwa Laharepouwa 4 Jawan Singh Bulun Charimaya Bulun dhunge 968.2 6 28436 7429362034 SHANKAR THAPA Bajhang Patadewal 8 KRISHNA BAHADUR THAPA SITADEVI THAPA BAYANA 968.3 7 33115 7429729007 niraj kumar karki Mugu Kotdanda 6 ram chandra karki raj kala karki luwai 968.4 8 30775 7369007044 MANOJ BAHADUR BUDHA Achham Risidaha 2 Amar Bahadur Budha Dewa Devi Budha Sanikhet 968.6 9 29144 6662015026 LOKENDRA BAHADUR SINGH Dailekh Chamunda 1 PURA SINGH KARNASHILA SHAHI Palta 968.7 10 30158 7459010030 khemraj Sarki Humla Maila 2 Manrup Sarki Dhauli Sarki tajakot 968.7 11 30416 7436010092 AJAY MAHATO Bara Dahiyar 6 Bayanath Mahato Bigni Sahani Malahi Dahiyar 968.7 12 30792 7462050002 JAGAT B. K Kalikot Ranchuli 2 Anipal bk Biuri bk Ratada 968.7 13 31833 7463020058 SURENDRA PRASAD SIMKHADE Jumla Dhapa 7 Ganesh Prasad Simkhade Ram Simkhade Bistabada 968.7 14 35029 7363004002 NISHA HAMAL Jumla Narakot 2 DHARMAL BDR HAMAL DHAN LAXMI HAMAL NARAKOT 968.7 15 28683 7359004084 SITA PHADERA Humla ShreeNagar -

Notice Fifth Lot for All PMT Upto 2075.10.13 Selected & Alternate 2Nd Quintile

मत / / गतेको "गोरखाप दैनक "मा काशत सुचना अनुसार ावधक श ालयहमा डलोमा तहमा भनाx भएर वगत (चार पटक ) मा परयोजनाले सुचना काशन गदाx तो"कएको #यादभ$ आवेदन दताx गराउन छु टेका व(याथ*हले छा$वि-तृ आवेदन (Scholarship Application) फाराम परयोजनाको वेवसाइट www.event.gov.np बाट डाउनलोड गर2 भरेर श ालयले मा3णत गर2 प"रयोजना स%चवालय , वु'नगरमा मत /( /() काया* य समयभ दताx गराउनुहोला । सो5ह सुचना अनुसार डलोमा तहमा बाँक8 रहेका 99 कोटामा छा$वि-तमाृ छनोट गन: योजनका लाग पुवx काशन भएको पएमट2 यो;यता<म अनुसारको =>?@ जनाको नामावल2 । नोट : आवेदन फाराम प"रयोजनाका पुवx सुचनाह1 अनुसार दताx ग"रसकेका 2व3याथ5ह1ले भनु x नपन6 । Selected candidates for Diploma Ward Token VDC/Municipa PMT SN. SLC Reg No Name District Numb Father Mother Village No lity Score er 1 34871 7416018187 SRIJANA KUMARI MAHATO Siraha RamnagarMirchaiya 7 BINDESHWAR MAHATO SUDI RAM DULARI DEVI BAN KARYALAYA CHOWK884.5 2 28644 7259004015 DANSINGH ROKAYA Humla ShreeNagar 5 Barkhe Rokaya Gorikala Parki Rokaya Village 899 3 28719 7059004006 BANDANA PHADERA Humla ShreeNagar 4 Netra Phadera Pushi Phadera Phadera Gaun 905 4 32936 7224003027 JEEWAN KUMAR NEUPANE Rasuwa Dhaibung 4 Khem Raj Neupane Chet Kumari Neupane Katunje 907.5 5 32696 7063022017 KAMAL ROKAYA Jumla Lihi(Rara) 6 MAN BAHADUR ROKAYA MANMA ROKAYA LIHI 910 6 32817 7124013003 Ghyu Jyalmo Tamang Rasuwa Gatlang 8 Kawa Tamang Dawa Chamo Tamang Gre 910.5 7 29380 6562005014 Dipak Kumar Shahi Kalikot Jubika 6 Harsa Bahadur Shahi Padma Shahi Jubitha 911.7 8 30311 7372001067 DEEPA PARIYAR Doti Dipayal Silgadhi N.P.5 DILIP PARIYAR NIRMALA PARIYAR SILGADI 915.5 -

How Does Social Protection Contribute to Social Inclusion in Nepal?

February 2014 Report How does social protection contribute to social inclusion in Nepal? Evidence from the Child Grant in the Karnali Region Tej Prasad Adhikari1, Fatik Bahadur Thapa1, Sonam Tamrakar1, Prakash Buda Magar1, Jessica Hagen-Zanker2 and Babken Babajanian2 1NEPAN 2ODI This study uses a social exclusion lens to analyse the effects of Nepal’s Child Grant in Karnali region and tests assumptions about the role social protection can play in contributing to social inclusion and poverty reduction. The study used mixed methods and employed a quasi-experimental impact evaluation. The findings show that in the first three years of implementation, the Child Grant has had only small effects on some indicators of social inclusion, most notably access to a more diversified diet. The research suggests that the impact of the Child Grant is limited by both design and implementation bottlenecks. Shaping policy for development odi.org Preface This report is part of a wider research project that assessed the effectiveness and relevance of social protection and labour programmes in promoting social inclusion in South Asia. The research was undertaken in collaboration with partner organisations in four countries, examining BRAC’s life skills education and livelihoods trainings for young women in Afghanistan, the Chars Livelihoods Programme and the Vulnerable Group Development Programme in Bangladesh, India’s National Health Insurance Programme (RSBY) in Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh and the Child Grant in the Karnali region of Nepal. Reports and briefings for each country and a paper providing cross-country analysis and drawing out lessons of relevance for regional and international policy can be found at: www.odi.org/sp-inclusion. -

Kalikot-District-Prayer-Guide-Nepali

g]kfn b]zsf] nfuL k|fy{fgf ug{' xf]: x'Dnf d'u' h'Dnf sfnLsf]6 8f]Nkf s0f{fnL, sfnLsf]6 o]z" v|Li6sf] gfpFdf ;a}nfO{ ho dl;x Û xfd|f] ;'Gb/ b]zsf] x/]s ufpFsf] lglDt k|fy{gf ug{ cfk"mnfO{ xfdL ;Fu} ;lDk{t ug'{ ePsf] nfuL wGojfb lbbF5f}+ . o]z" cfk}mn] x/]s ufpFnfO{ k|]d ug'{ x'GYof] eGg] gd'gf cfkmgf] ;]jfsfO{sf] ;dodf cfkmg} r]nfx?nfO{ Pp6f zx/ b]lv csf]{ ufFpx?df hfFbf b]vfpg' eof] . csf]{ s'/f], o]z" cfkm}n] cfkmgf] r]nfx?nfO{ cfk'mn] u/]em}+ ug{ l;sfpg] / ljleGg ufpFdf k7fpg] sfd ug'{ eof] . afbdf, pxfFn] ;Q/L hgfnfO{ klg b'O{–b'O{ hgf u/L ljleGg ufpFdf k7fpg' eof] . n'sf *–!) cWofo . t/, xfdLx?n] cfh s;/L xfd|f] b]z g]kfnsf] #,(*$ uf=lj=;= sf] lglDt k|fy{gf ug]{< gx]Dofxsf] ;dodf, o?zn]dsf] kv{fn elTsPsf] va/ ox'bfsf bfHo–efO{x?n] NofP . o; kf7df kv{fn zAbn] /Iff, ;'/Iff, cflzif clg Pp6f eljiosf] cfzf b]vfpFb5 . gx]Dofxn] k|fy{gf u/], pkjf; a;], clg dflg;x?sf] kfksf] lglDt kZrtfk klg u/] . k/dk|e'n] gx]Dofxsf] k|fy{gfsf] pQ/ lbg'eof] . w]/} 7"nf] lhDd]jf/L ;f/f kv{fn k'g lgdf0f{ ug'{ kg]{ sfd pxfFsf] cflzif / cg'u|xdf ;Defj eof] . x/]sn] w]/} lj/f]w / ;tfj6 ;fdfgf ug'{ k/]tf klg cfkmgf] c3f8Lsf] kv{fnsf] lgdf0f{ ul//x] . o;/Lg}, xfd|f] nflu x/]s ufpF kv{fnsf] Pp6f O§f h:t} xf] . -

Facility Based Assessment for Reproductive Health Commodities and Services

Facility Based Assessment for Reproductive Health Commodities and Services FINAL REPORT United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Shanta Bhawan Road, Jhamsikhel Lalitpur, Nepal Submitted By Nepal Development Research Institute Shree Durbar Tole, Pulchowk, Lalitpur, Nepal Submission date: 16th March 2015 i This report is a product of research on "Facility Based Assessment for Reproductive Health Commodities and Services “carried out by Nepal Development Research Institute with the financial support of United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) from October 2014 to January 2015 Study Team • Dr. Basu Dev Pandey, Team Leader • Prof. Naveen Shrestha, Senior Consultant Expert • Dr. Jaya Kumar Gurung, Project Coordinator • Dr. Rabita Mulmi, Field Survey Coordinator • Ms. Saruna Ghimire, Consultant Expert • Ms. Sona Shakya , Senior Research Associate Report By: Nepal Development Research Institute Shree Durbar Tole, Pulchowk, Lalitpur www.ndri.org.np ii Acknowledgement It is a great pleasure for Nepal Development Research Institute (NDRI) to accomplish this research in collaboration with concern departments of Government of Nepal and UNFPA/Nepal. We thank UNFPA for entrusting NDRI and making congenial environment for this research work. It's immense pleasure to acknowledge the representatives of Nepal Government's agencies particularly Dr. Senendra Raj Upreti, Director General , Department of Health services, Dr. Bhim Singh Tinkari, Director of Logistic Management Division (LMD), Dr. Pushpa Chaudhari, Director, Family Health Division (FHD), Bhogendra Raj Dotel, Senior Public Health Administrator, Mr. Gyan Bahadur BC, Planning Officer (LMD), Krishna Ghimire, Joint Secretary (LMD), Upendra Dhungana (LMD) for their invaluable cooperation into various ways; valuable inputs in the inception phase of project, important contribution in training to field researchers, arranging the district and regional level health facilities for their cooperation, and providing suggestions in the draft report. -

RAR of Kalikot

Rapid Assessment Report On Hunger Situation in Kalikot 12 ? 21 July, 2006 1 1 The Lutheran World Federation Nepal Western Region Coordination Unit Nepalgunj, Banke Rapid Assessment Report On Hunger Situation in Kalikot (12 ? 21 July, 2006) Introduction Since 1984, the Lutheran World Federation-Nepal, a humanitarian organization, has been launching programmes related to relief and rehabilitation, and people’s empowerment for sustainable development. Kalikot district that lies in the Karnali Zone reeled under a natural disaster on April 10, 2006. Incessant rain and ferocious hailstorm damaged standing crops and ripe vegetables. Wheat, barley, Uwa, potatoes, fruits and so on were ruined by the rainfall. As food crisis struck the district, villagers sold their properties, jewellery, utensils, and took loans to meet their ends. Various news media gave massive coverage to this incident. Hence, LWF Nepal’s Western Regional Coordination Unit (WRCU) formed a Rapid Assessment Team (RAT) and sent it on July 12, 2006 to conduct research and survey of the district, with the objective of exploring the possibility of providing the victims of food crisis with some relief and assistance. The LWF Nepal, WRCU organized an orientation program to assess the situation and provided guidelines and format for RAT on 12 July, 2006. Objectives · To inspect and survey the areas affected by drought and ha ilstorm in Kalikot. · To acquire a summary understanding of the situation by organizing an interaction programme and establishing coordination with governmental and non-governmental organizations, political parties, civil society and other organizations concerned in Kalikot district. · To conduct a study in and to map the areas in accordance with the standards set earlier. -

Global Initiative on Out-Of-School Children

ALL CHILDREN IN SCHOOL Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children NEPAL COUNTRY STUDY JULY 2016 Government of Nepal Ministry of Education, Singh Darbar Kathmandu, Nepal Telephone: +977 1 4200381 www.moe.gov.np United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Institute for Statistics P.O. Box 6128, Succursale Centre-Ville Montreal Quebec H3C 3J7 Canada Telephone: +1 514 343 6880 Email: [email protected] www.uis.unesco.org United Nations Children´s Fund Nepal Country Office United Nations House Harihar Bhawan, Pulchowk Lalitpur, Nepal Telephone: +977 1 5523200 www.unicef.org.np All rights reserved © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) 2016 Cover photo: © UNICEF Nepal/2016/ NShrestha Suggested citation: Ministry of Education, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Global Initiative on Out of School Children – Nepal Country Study, July 2016, UNICEF, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2016. ALL CHILDREN IN SCHOOL Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children © UNICEF Nepal/2016/NShrestha NEPAL COUNTRY STUDY JULY 2016 Tel.: Government of Nepal MINISTRY OF EDUCATION Singha Durbar Ref. No.: Kathmandu, Nepal Foreword Nepal has made significant progress in achieving good results in school enrolment by having more children in school over the past decade, in spite of the unstable situation in the country. However, there are still many challenges related to equity when the net enrolment data are disaggregated at the district and school level, which are crucial and cannot be generalized. As per Flash Monitoring Report 2014- 15, the net enrolment rate for girls is high in primary school at 93.6%, it is 59.5% in lower secondary school, 42.5% in secondary school and only 8.1% in higher secondary school, which show that fewer girls complete the full cycle of education. -

RFP Documents Before the Proposal Submission Date

REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL RFP 01 F/Y 2066/67 Monitoring and Evaluation of the Basic Telecommunication Service Licensee of license no:- Basic 03 (Nepal Satellite Telecom Pvt. Ltd) October 2009 RFA Selection of Consultant Basic-03 2/ 73 Section 1. Letter of Invitation Nepal Telecommunications Authority Bluestar Office Complex, Tripureshwor, Kathmandu Dear Mr./Ms 1. Nepal Telecommunications Authority (NTA) invites proposals to provide the consulting services on Monitoring and Evaluation of the Basic Telecommunication Service Licensee of license no:- Basic 03 (Nepal Satellite Telecom Pvt. Ltd) with the objective to supervise the implementation of the Roll out Obligation of the Licensee. More details on the services are provided in the Terms of References . 2. A firm/consultant will be selected under Least Cost Selection (LCS) method and procedures described in this RFP 3. The RFP includes the following documents: Section 1 - Letter of Invitation Section 2 - Instructions to Consultants (including Data Sheet) Section 3 - Technical Proposal - Standard Forms Section 4 - Financial Proposal - Standard Forms Section 5 - Terms of Reference Section 6 - Standard Forms of Contract 4. Please inform us in writing at the following address before the closing date mentioned in this RFP (a) Whether you will submit a proposal alone or in association which shall be in the form of a Joint Venture with joint and several liabilities. 5. NTA reserves all rights to accept or reject any or all proposals without assigning any reason whatsoever. Yours sincerely, _____________________________ Mr. Bhesh Raj Kanel Chairman, Nepal Telecommunications Authority Date :- 5th November 2009 RFA Selection of Consultant Basic-03 3/ 73 Section 2. -

EPI) Clinics in One District

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A. Introduction The Family Health Division of Nepal’s Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) recognises the importance of strengthening the provision of family planning and counselling for healthy timing and spacing of births, particularly for women during the first year after child birth. WHO recommends a two year interval between births as a means to reduce the risk of adverse maternal and child health outcomes (WHO 2005). Yet in Nepal, one fifth of births occur within that two year period and 50% within less than 35 months (DHS 2011). Only 9% of women who had a live birth in the past 5 years recall being counselled on family planning during postpartum check-up (DHS 2011). This piece of operational research responds directly to the huge unmet need and demand in Nepal for family planning information and services by integrating family planning services into Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) clinics in one district. It investigates whether the integrated service can increase uptake of family planning services among women in the district, particularly among new users, without negatively impacting on the delivery of the (highly successful) core EPI service. The Family Health Division (FHD) led the operational research in coordination with Child Health Division (CHD). The research was designed and implemented with technical support from the Nepal Health Sector Support Programme (NHSSP) with monitoring support from the Health Research and Social Development Forum (HERD). The research began in July 2012 and was monitored and evaluated using the following methods: 1. On-going monitoring of intervention sites — Focused monitoring was conducted in 20 selected health facilities and routine monitoring data was collected from EPI registers at all the sites.