Representative and Responsive Bureaucracy In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mise En Page 1

ASIA PACIFIC NEPAL FEDERAL COUNTRY BASIC SOCIO-ECONOMIC INDICATORS INCOME GROUP: LOW INCOME LOCAL CURRENCY: NEPALESE RUPEE (NPR) POPULATION AND GEOGRAPHY ECONOMIC DATA Area: 147 180 km 2 GDP: 79 billion (current PPP international dollars), 2 697 dollars per inhabitant (2017) Population: 29.305 million inhabitants (2017), an increase of 1.2% Real GDP growth: 7.5 % (2017 vs 2016) per year (2010-2015) Unemployment rate: 2.7 % (2017) Density: 199 inhabitants / km 2 Foreign direct investment, net inflows (FDI): 196 (BoP, current USD millions, 2017) Urban population: 19.3 % of national population Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF): 34% of GDP (2017) Urban population growth: 3.2 % (2017 vs 2016) HDI: 0.574 (medium), ranking 149 (2017) Capital city: Kathmandu (4.5 % of national population) Poverty rate: 15% (2010) MAIN FEATURES OF THE MULTI-LEVEL GOVERNANCE FRAMEWORK Following the end in 2006 of a decade-long civil war, Nepal’s governance framework is currently in the transition from being a Monarchy to a multiparty democratic republic. With the promulgation of the new Constitution in 2015, Nepal moved from a unitary form of government to a federal one with a strong focus on decentralization based on “cooperative federalism”. The new federation has three tiers of government, namely federal, state and local, whereby powers shall be exercised pursuant to the Constitution and the state laws. The Constitution has assigned both exclusive and concurrent powers, to be jointly exercised by the federal and the state levels or jointly by all three tiers of government. The jurisdiction of the local governments is outlined under Schedule 8 of the Constitution, which establishes that local governments are responsible for development activities and for mobilizing the necessary resources to carry out such activities. -

Cultural Crisis of Caste Renouncer: a Study of Dasnami Sanyasi Identity in Nepal

Molung Educational Frontier 91 Cultural Crisis of Caste Renouncer: A Study of Dasnami Sanyasi Identity in Nepal Madhu Giri* Abstract Jat NasodhanuJogikois a famous mocking proverb to denote the caste status of Sanyasi because the renouncer has given up traditional caste rituals set by socio-cultural institutions. In other cultural terms, being Sanyasi means having dissociation himself/herself with whatever caste career or caste-based social rank one might imagine. To explore the philosophical foundation of Sanyasi, they sacrificed caste rituals and fire (symbol of power, desire, and creation). By the virtues of sacrifice, Sanyasi set images of universalism, higher than caste order, and otherworldly being. Therefore, one should not ask the renouncer caste identity. Traditionally, Sanyasi lived in Akhada or Matha,and leadership, including ownership of the Matha transformed from Guru to Chela. On the contrary, DasnamiMahanta started marital and private life, which is paradoxical to the philosophy of Sanyasi.Very few of them are living in Matha,but the ownership of the property of Mathatransformed from father to son. The land and property of many Mathas transformed from religious Guthi to private property. In terms of cultural practices, DasnamiSanyasi adopted high caste culture and rituals in their everyday life. Old Muluki Ain 1854 ranked them under Tagadhari, although they did notassert twice-born caste in Nepal. Central Bureau of Statistics, including other government institutions of Nepal, listed Dasnamiunder the line ofChhetri and Thakuri. The main objective of the paper is to explore the transformation of Dasnami institutional characteristics and status from caste renunciation identity to caste rejoinder and from images of monasticism, celibacy, universalism, otherworldly orientation to marital, individualistic lay life. -

Nepal, November 2005

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Nepal, November 2005 COUNTRY PROFILE: NEPAL November 2005 COUNTRY Formal Name: Kingdom of Nepal (“Nepal Adhirajya” in Nepali). Short Form: Nepal. Term for Citizen(s): Nepalese. Click to Enlarge Image Capital: Kathmandu. Major Cities: According to the 2001 census, only Kathmandu had a population of more than 500,000. The only other cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants were Biratnagar, Birgunj, Lalitpur, and Pokhara. Independence: In 1768 Prithvi Narayan Shah unified a number of states in the Kathmandu Valley under the Kingdom of Gorkha. Nepal recognizes National Unity Day (January 11) to commemorate this achievement. Public Holidays: Numerous holidays and religious festivals are observed in particular regions and by particular religions. Holiday dates also may vary by year and locality as a result of the multiple calendars in use—including two solar and three lunar calendars—and different astrological calculations by religious authorities. In fact, holidays may not be observed if religious authorities deem the date to be inauspicious for a specific year. The following holidays are observed nationwide: Sahid Diwash (Martyrs’ Day; movable date in January); National Unity Day and birthday of Prithvi Narayan Shah (January 11); Maha Shiva Ratri (Great Shiva’s Night, movable date in February or March); Rashtriya Prajatantra Diwash (National Democracy Day, movable date in February); Falgu Purnima, or Holi (movable date in February or March); Ram Nawami (Rama’s Birthday, movable date in March or April); Nepali New Year (movable date in April); Buddha’s Birthday (movable date in April or May); King Gyanendra’s Birthday (July 7); Janai Purnima (Sacred Thread Ceremony, movable date in August); Children’s Day (movable date in August); Dashain (Durga Puja Festival, movable set of five days over a 15-day period in September or October); Diwali/Tihar (Festival of Lights and Laxmi Puja, movable set of five days in October); and Sambhidhan Diwash (Constitution Day, movable date in November). -

Download Publication

No. 43 Working Papers Working Negotiating Between Unequal Neighbours: India‘s Role in Nepal‘s Recent Constitution-Making Process Prakash Bhattarai December 2018 1 Negotiating Between Unequal Neighbours: India’s Role in Nepal’s Recent Constitution-Making Process1 Prakash Bhattarai ABSTRACT Nepal’s post-conflict constitution-making process has seen the involvement of many international actors. While studies on democracy promotion, to this day, mainly focus on Western “donors” and international organizations, this paper looks at the role played by India in the complicated process of moving from a peace agreement to the establishment of an inclusive, democratic constitution in Nepal. More specifically, it is analysed how a powerful neighbouring democracy (India) participated in what is essentially a domestic negotiation process (constitution-making) with a view to influencing the emerging demo- cratic regime. In terms of the issues on the negotiation table, the analysis shows that India, in pushing for an inclusive constitution, pursued the specific agenda of supporting the inclusion of the Madheshis, an ethnic group mostly living in Nepal’s Terai region. In terms of negotiation strategies, the paper identifies four different ways in which India tried to influence the constitution: high-level dialogue; economic blockade; international coalition building; and targeted support of domestic oppositional forces in Nepal. Com- prehensive as this negotiation strategy was, it only met with partial success. Parameters that limited India’s influence included the domestic strength and legitimacy of the official Nepali position (elite alignment; popular support) as well as scepticism concerning In- dia’s role in Nepal, which was reinforced by India’s overly partisan agenda. -

Framing of Nepal's Constitution

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2017 Framing of Nepal’s Constitution: How Indian and Nepali National Media Covered the Controversy Surrounding the Ratification of Nepal’s Constitution in 2015 Amir Joshi Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Joshi, Amir, "Framing of Nepal’s Constitution: How Indian and Nepali National Media Covered the Controversy Surrounding the Ratification of Nepal’s Constitution in 2015" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 15331. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/15331 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Framing of Nepal’s Constitution: How Indian and Nepali national media covered the controversy surrounding the ratification of Nepal’s Constitution in 2015 by Amir Joshi A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Journalism and Mass Communication Program of Study Committee: Raluca Cozma, Major Professor Daniela V. Dimitrova Olga Chyzh Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2017 Copyright © Amir Joshi, 2017. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES iv ABSTRACT v CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW 2 Introduction and Significance of Study 2 Constitution and Nepal India Ties 6 Madhesh and Minority Issues 7 Conflict and Media 8 Framing Theory 9 Research Questions 13 CHAPTER 3. -

A Case Study of Sarki People from Naubise Vdc of Dhading District

16 Occasional Papers, Vol 11 SOCIO-CULTURAL SUBJECTIVITIES OF LANDLESSNESS IN NEPAL: A CASE STUDY OF SARKI PEOPLE FROM NAUBISE VDC OF DHADING DISTRICT Jailab Rai * Introduction Land is a primary resource for an agrarian economy in underdeveloped countries like Nepal. More than 85 percent of Nepal’s population lives in rural areas and more than 60 percent of the economically active population is involved in agriculture (HMG, 2003). Rapid population growth and increasing pressure on land resources to earn the much needed calorie is a major challenge in the country (Graner, 1997). In this context, the study of landlessness remains an important aspect of national agenda (Shrestha, 2001), particularly in the national inclusion process (Gurung, 2006). Moreover, the study of landlessness has become a policy debate and an issue of concern in the debates on national economic development (Shrestha, 2001). The sociological and anthropological understanding of landlessness has its own importance since it requires the analysis of cultural dimensions (Caplan, 1970 and 1972) as socio-cultural subjectivities in a historical context. The access to land resources or landlessness is an important social issue, which can be linked with social and cultural aspects of landless people as socio-cultural subjectivities in drawing out the implication of their access to land resources. This study deals with the socio-cultural subjectivities of landlessness with a focus on the Sarki people in the central hills of Nepal who are among the extremely marginalized groups of people in terms of the access and ownership to land resources. It reviews the process of * Jailab Rai holds M. -

Human Security in Nepal: Concepts, Issues and Challenges

Human Security in Nepal: Concepts, Issues and Challenges 1 Human Security in Nepal: Concepts, Issues and Challenges Edited by Bishnu Raj Upreti Rajan Bhattarai Geja Sharma Wagle Published by Nepal Institute for Policy Studies and South Asia Regional Coordination Office of NCCR (North-South) Kathmandu 2013 Citation: Upreti BR, Bhattarai R, Wagle GS, editors. 2013. Human Security in Nepal: Concepts, Issues and Challenges. Kathmandu: Nepal Institute for Policy Studies (NIPS) and South Asia Regional Coordination Office of NCCR (North-South). Copyright © 2013 by NIPS and NCCR North-South, Kathmandu, Nepal. All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-9937-2-5257-7 Subsidised price: NRs. 400/- Layout & cover design: Jyoti Khatiwada Printed by: Heidel Press Pvt. Ltd. Dillibazar, Kathmandu Cover Concept: Safal Ghimire Disclaimer: The content and materials presented in this book are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the institution with which the authors are affiliated. Dedication To the millions of people who are suffering from human insecurity. Acknowledgements The issue of security is a little-debated matter in our academic domain. When it comes to dealing human security, we often confront questions like: What constitutes human security? Why has it become so pertinent for a country like Nepal? How can human security be made tenable? These and many other questions on human security came to our mind before we decided to publish this book. This is our small attempt to address some of those questions and generate debate and discussion on the increasingly changing security dynamics of Nepal. This book is the collective outcome of the efforts of several people. -

A Case Study of Jana Andolan II in Nepal

Occasional Paper: Peace Building Series No.1 FutureGenerations Applied Community Graduate School Change and Conservation PeoPle’s ParticiPation in conflict transformation: a case study of Jana andolan II in nePal Bandita Sijapati Social Science Baha February 2009 Occasional Papers of the Future Generations Graduate School explore community-based approaches to social development, health, nature conservation, peace building, and governance. Faculty, alumni, and partner organizations present their field studies and applied research. www.future.edu People’s Participation in Conflict Transformation: A Case Study of Jana Andolan II in Nepal Rise from every village, rise from every settlement To change the face of this country, rise Those who have a pen in hand, bring your pen and rise Those who can play an instrument, bring your instrument and rise Those who have a tool in hand, bring your tool and rise Those who have nothing at all, bring your voice and rise.1 I. INTRODUCTION In April 2006, there was a country-wide people’s movement in Nepal, popularly known as the Jana Andolan II,2 against King Gyanendra’s direct rule3 following a 12-point understanding reached between the Seven Party Alliance4 and the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist), which was leading a communist insurgency against the state. The 19-day-long Jana Andolan II5 (People’s Movement II) ended direct rule by Gyanendra, forced him to return power to the reinstated parliament, and created a conducive environment for the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) between the government and the rebel Maoists in November 2006. The success of Jana Andolan II in thus ending the decade-long conflict that had affected all parts of the country has thus been hailed by many as being exemplary of the ways in which engaged citizenry and communities at the local level can have an impact on the resolution and transformation of violent conflict at the national level. -

Access to Land Resource: Dalits and Their Livelihood Insecurity

CHAPTER 7 Access to Land Resource: Dalits and their Livelihood Insecurity Purna B. Nepali 7.1 Background Land is a broad indicator of socioeconomic status in an agrarian society like Nepal (The World Bank, 2006). It constitutes a fundamental productive asset (Ellis, 2000), the principal source of livelihood and power, a means of pride, dignity, prestige and a symbol of prosperity (CBS, 2002; CSRC, 2001; ICIMOD, 2000; Regmi, 1999; Upreti, 2004). Endowed with these characteristics being, and also a fundamental economic asset, it can reduce vulnerability and build resilience against poverty. Land is not only a productive agricultural asset, it may be of potential advantage in a local labor market (e.g. through increased bargaining power), and in international labor market (e.g. as a collateral to obtain loan for migration). Land ownership may serve as productive and entrepreneurial activities (both observed and unobserved) (The World Bank, 2006). In Nepal, political and economic power was consolidated by the upper castes, interlinking it with the Hindu caste system. The priestly Brahmans were at the top of ritual order, with the Kshatriya (kings and warriors) just beneath them and in control of the political order; next came the Vaishya (merchants), and the Sudra (peasants and laborers) came at the bottom. Beneath them all were the occupational groups, considered as "impure", and untouchables, and today as Dalits 77 . In the Hills, in-migrating 77 The term ‘Dalit’, is understood to refer to the untouchable or Achhoot or the term connotes in the sense understood by the Old Legal Code of 1854, “Pani nachalne chhoi chhito halnu parne jat” (caste from whom water is not accepted and 163 Hindus of Caucasoid stock made up the castes of priests and warriors. -

Piers Locke: 'The Hattisar: the Integral Role of the Elephant Stable in The

1 Piers Locke: ‘The Hattisar: The Integral Role of The Elephant Stable in the Apparatus of lowland Nepali Park Management’ Slide 1: Introduction In this presentation I will examine the Nepali institution of the elephant stable or hattisar, tracing its history of change and continuity within the broader context of Nepali state and society. I argue that although the uses for which captive elephants are deployed has changed as Nepal has embraced modern concerns of political reform, development and biodiversity conservation, the institutional sub-culture of the government stable or sarkari hattisar remains rooted in the structures and practices that emerged in the era of regal hunting expeditions for which it was originally established. With its own elaborated system of ranks and roles, I argue that the hattisar retains its own distinctive Tharu character as an enclaved and total institution. By providing an encompassing social environment in which men live and work, and are required to make intense and enduring commitments to their elephant companions, elephant handlers or hattisares represent an occupational community with their own distinct group habitus of attitudes, dispositions, competencies and forms of know-how, which is essential to the management of Nepal’s lowland national parks and conservation areas. So that’s the basic gist of what I am trying to say today, although I should make a few caveats to begin with. My primary aim here is to provide an account of the history of the institution of the hattisar; to provide a contextual understanding of how it has come to take the form that it has and fulfil the functions that it does in a state committed to a complementary marriage of biodiversity conservation and nature tourism. -

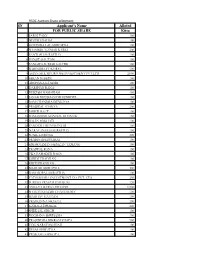

Applicant's Name Alloted for PUBLIC SHARE Kitta

RSDC Auction Share Allotment SN Applicant's Name Alloted FOR PUBLIC SHARE Kitta 1 SAROJ PANT 200 2 NITESH DAHAL 100 3 GOVINDA LAL SHRESTHA 100 4 SHAMBHU KUMAR KARKI 200 5 SANTOSH SHRESTHA 100 6 RANJIT GAUTAM 150 7 SANGITA SUBEDI KHATRI 100 8 RABINDRA POKHREL 100 9 ASIAN MULTIPURPOSE INVESTMENT PVT.LTD. 2,000 10 KIRAN SUBEDI 160 11 ARCHANA KUMARI 100 12 DARSHAN RANA 100 13 RUKESH MAHARJAN 450 14 JANAK BHUSHAN DHAUBHDEL 100 15 RAM CHANDRA DEVKOTA 100 16 PRAJJWAL SHAKYA 200 17 SMRITI RAUT 100 18 RAMASHISH MANDAL DHANUK 150 19 RAJAN BAKHATI 100 20 SANDESH DHAUBANJAR 100 21 NARAYAN DAS SHRESTHA 150 22 SUNIL GURUNG 300 23 PRABIN BHATTARAI 100 24 KRISHNAMAN HEMZAN TAMANG 100 25 PRAJWAL RANA 100 26 EKA BAHADUR RANA 100 27 SMRITI PRADHAN 100 28 KRITI PRADHAN 100 29 MAHESH SHRESTHA 300 30 RAM GOPAL SHRESTHA 100 31 PATHIBHARA INVESTMENT CO. PVT. LTD. 250 32 SURESH PRASAD PARAJULI 120 33 AMULYA RATNA STHAPIT 1,500 34 SHAKTI KUMARI CHAUDHARY 100 35 MADHAV GAUTAM 100 36 PRASSANNA SHAKYA 200 37 KAMALA DHAKAL 220 38 SHEETAL SINGH 100 39 ROCHANA SHRESTHA 200 40 PRASIDDHA BIKRAM THAPA 500 41 YOG NARAYAN SHAH 100 42 DIBAS SHRESTHA 100 43 PRAKASH SAPKOTA 100 44 BINU POUDEL THAPA 210 45 SHAKTI AMAR SINGH 250 46 NAWRAJ SIGDEL 150 47 KUL BAHADUR PANDIT 240 48 RAVINDRA ACHARYA 200 49 RAM MANOHAR SHRESTHA 100 50 BASANT KUMAR MISHRA 100 51 JOON SHRESTHA 200 52 PRATAP MAN SHRESTHA 500 53 DURGA BAHADUR BANIYA 1,500 54 GUHESWORI MERCHANT BANKING AND FINANCE 5,000 55 MUNA DEVI RAWAL 100 56 KUSUM SHRESTHA 100 57 CHHABILAL GYAWALI 550 58 YOGA RAJ JOSHI 100 59 NABINDRA -

Chronology of Major Political Events in Contemporary Nepal

Chronology of major political events in contemporary Nepal 1846–1951 1962 Nepal is ruled by hereditary prime ministers from the Rana clan Mahendra introduces the Partyless Panchayat System under with Shah kings as figureheads. Prime Minister Padma Shamsher a new constitution which places the monarch at the apex of power. promulgates the country’s first constitution, the Government of Nepal The CPN separates into pro-Moscow and pro-Beijing factions, Act, in 1948 but it is never implemented. beginning the pattern of splits and mergers that has continued to the present. 1951 1963 An armed movement led by the Nepali Congress (NC) party, founded in India, ends Rana rule and restores the primacy of the Shah The 1854 Muluki Ain (Law of the Land) is replaced by the new monarchy. King Tribhuvan announces the election to a constituent Muluki Ain. The old Muluki Ain had stratified the society into a rigid assembly and introduces the Interim Government of Nepal Act 1951. caste hierarchy and regulated all social interactions. The most notable feature was in punishment – the lower one’s position in the hierarchy 1951–59 the higher the punishment for the same crime. Governments form and fall as political parties tussle among 1972 themselves and with an increasingly assertive palace. Tribhuvan’s son, Mahendra, ascends to the throne in 1955 and begins Following Mahendra’s death, Birendra becomes king. consolidating power. 1974 1959 A faction of the CPN announces the formation The first parliamentary election is held under the new Constitution of CPN–Fourth Congress. of the Kingdom of Nepal, drafted by the palace.