The Monroe County Intermediate School District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master Plan 2017

RAAIISSIINNVVIILLLLEE TOOWWNNSSHHIIPP R T Approved and Adopted MM AASSTTEERR PPLLAANN March 3, 20 14 Adopted September 18, 2017 The Raisinville Township Planning Commission approves this Master Plan as a guide for the future development of the Township John Delmotte Planning Commission Chair September 18, 2017 Page 2 Adopted September 18, 2017 | RAISINVILLE TOWNSHIP Master Plan A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS Township Board Gerald Blanchette, Supervisor Brenda Fetterly, Clerk Rose Marie Meyer, Treasurer Keith Henderson, Trustee Thomas Woelmer, Trustee Planning Commission John Delmotte, Chair Michael Jaworski, Vice-Chair Ann Nickel-Swinkey, Secretary Craig Assenmacher, Commissioner Kevin Kruskie, Commissioner Gary Nowitzke, Commissioner Thomas Woelmer, Board Representative Prepared by: Assisted by: The Mannik & Smith Group, Inc. RAISINVILLE TOWNSHIP Master Plan | Adopted September 18, 2017 Page i This page intentionally left blank Page ii Adopted September 18, 2017 | RAISINVILLE TOWNSHIP Master Plan C ONTENTS I NTRODUCTION Purpose and Legislative Authority of the Master Plan ........................................... 1 How the Plan Is to Be Used ................................................................................... 2 Plan Update ........................................................................................................... 2 Planning Process ................................................................................................... 2 Plan Organization.................................................................................................. -

Center for Educational Performance and Information (CEPI)

Center for Educational Performance and Information (CEPI) State of Michigan 2010 Cohort 4-Year & 2009 Cohort 5-Year Graduation and Dropout Rate Reports Questions? Contact: 517.335.0505 e-mail: [email protected] Table of Contents Documentation Overview of Michigan’s Cohort Graduation and Dropout Rates ............................................................. 3 2010 Cohort Four-Year Graduation Rate ............................................................................................... 3 2010 Cohort Four-Year Dropout Rate .................................................................................................... 4 Reading the 2010 Cohort Four-Year Graduation and Dropout Rate Report ........................................... 4 2009 Cohort Five-Year Graduation and Dropout Rates .......................................................................... 5 Reading the 2009 Cohort Five-Year Graduation and Dropout Rate Report ............................................ 5 Data Validation and Appeals Process .................................................................................................... 6 Reports 2010 Cohort Four-Year Graduation and Dropout Rates for the State of Michigan………………………...7 2010 Cohort Four-Year Graduation and Dropout Rates for Local Education Agency (LEA) ................... 7 2010 Cohort Four-Year Graduation and Dropout Rates for Public School Academy (PSA) ................. 52 2010 Cohort Four-Year Dropout Rates for Intermediate School District (ISD) ..................................... -

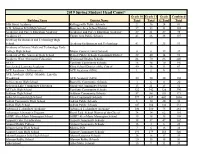

2019 Spring Student Head Count*

2019 Spring Student Head Count* Grade 10 Grade 11 Grade Combined Building Name District Name Total Total 12 Total Total 54th Street Academy Kelloggsville Public Schools 21 36 24 81 A.D. Johnston Jr/Sr High School Bessemer Area School District 39 33 31 103 Academic and Career Education Academy Academic and Career Education Academy 27 21 27 75 Academy 21 Center Line Public Schools 43 26 38 107 Academy for Business and Technology High School Academy for Business and Technology 41 17 35 93 Academy of Science Math and Technology Early College High School Mason County Central Schools 0 0 39 39 Academy of The Americas High School Detroit Public Schools Community District 39 40 14 93 Academy West Alternative Education Westwood Heights Schools 84 70 86 240 ACCE Ypsilanti Community Schools 28 48 70 146 Accelerated Learning Academy Flint, School District of the City of 40 16 11 67 ACE Academy - Jefferson site ACE Academy (SDA) 1 2 0 3 ACE Academy (SDA) -Glendale, Lincoln, Woodward ACE Academy (SDA) 50 50 30 130 Achievement High School Roseville Community Schools 3 6 11 20 Ackerson Lake Community Education Napoleon Community Schools 15 21 15 51 ACTech High School Ypsilanti Community Schools 122 142 126 390 Addison High School Addison Community Schools 57 54 60 171 Adlai Stevenson High School Utica Community Schools 597 637 602 1836 Adrian Community High School Adrian Public Schools 6 10 20 36 Adrian High School Adrian Public Schools 187 184 180 551 Advanced Technology Academy Advanced Technology Academy 106 100 75 281 Advantage Alternative Program -

Michig a N Educ a T

2019 MICHIGAN EDUCATION FALL THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN SCHOOL OF EDUCATION 2 Bastedo helped to develop Landscape, a tool that provides context about the opportunities that applicants have—or do not have—in their communities and high schools. His ongoing research informs college admissions practices and strategies, and will reveal the role that Landscape plays in efforts of colleges to admit a diverse freshman class. The newly launched TeachingWorks Resource Library supports teacher educa- tors with free, high-quality curriculum materials. We follow the researchers and FALL 2019 FALL product designers through their use of the design thinking process to discover • how they developed and refined the Resource Library and how it is being used. As educators, we empower students to be innovators. Ninth graders at The School at Marygrove, which we opened this fall in partnership with the Detroit Public Schools Community District, are taking Introduction to Human Centered Design and Engineering at their new school in northwest Detroit. Taught by the first “resident” of the Teaching School, Ms. Sneha Rathi, the curriculum was co-developed with a team of graduate students, staff, and faculty from the SOE. Students in Rathi’s class are learning how they can use design thinking to address challenges or needs in their community. I am proud of these young students; our teacher education graduate, Sneha Rathi; our graduate students; and our faculty and staff who are working together to build and study innovative education opportunities. Their work gives us all hope and inspiration. We also began work with the first cohort of Dow Innovation Teacher Fellows MICHIGAN EDUCATION EDUCATION MICHIGAN Dean Elizabeth Birr Moje at the SOE homecoming tailgate, October 5, 2019. -

The American Militia Phenomenon: a Psychological

THE AMERICAN MILITIA PHENOMENON: A PSYCHOLOGICAL PROFILE OF MILITANT THEOCRACIES ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Political Science ____________ by © Theodore C. Allen 2009 Summer 2009 PUBLICATION RIGHTS No portion of this thesis may be reprinted or reproduced in any manner unacceptable to the usual copyright restrictions without the written permission of the author. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Publication Rights ...................................................................................................... iii Abstract....................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER I. Introduction.............................................................................................. 1 II. Literature Review of the Modern Militia Phenomenon ........................... 11 Government Sources .................................................................... 11 Historical and Scholarly Works.................................................... 13 Popular Media .............................................................................. 18 III. The History of the Militia in America...................................................... 23 The Nexus Between Religion and Race ....................................... 28 Jefferson’s Wall of Separation ..................................................... 31 Revolution and the Church.......................................................... -

The Myth of the Hero

The Myth of the Hero by Bill Butler Revision: 20 July 2013 ONE On every beach there is a ninety-seven-pound weakling. He crouches where the The hero, then, is generated by the needs of ordinary mortals. He is the answer tides recede, glaring at the retreating backs of his girlfriend and the bully who to our prayers and will do those things which we are completely incapable of has just kicked sand in his face. What is he to do? Who will help him recover doing for ourselves. The genesis of literature and myth in which there are heroes his girl and his manhood? is in human need. At one end of the spectrum there are such figures as the Revenger, the Avenger, the Destroyer, Mike Hammer and Travis McGee. At the The headlines are a disaster. The economic situation is worsening with the other are Maitreya Buddha, Jesus Christ, and the Messiah of the Jews. All share rats of right and left deserting the ship as fast as they can. If inflation and a common genesis in human need for a good guy to ride in out of the sunset. unemployment continue to rise, the result has to be a political crisis leading to What he will do when he has dismounted depends on the situation. The anarchy or a dictatorship. We need a leader. Revengers will all solve their (and our) equations with bloodbaths, providing answers which are similar to Alexander’s when confronted with the problem Up to her elbows in the dirty dishwater of seven strange men, Snow White sighs of the Gordian Knot. -

Grantee Advised Grants Grants That Support SVCF's Grantmaking Strategies Total 10 Books a Home $256,500.00 $256,500.00 10,000 De

Grants that support SVCF's Grantee Advised Grants Total grantmaking strategies 10 Books A Home $256,500.00 $256,500.00 10,000 Degrees $5,000.00 $5,000.00 100 Women Charitable Foundation, Inc. $1,500.00 $1,500.00 1000 Friends of Oregon $1,500.00 $1,500.00 10000 Cries for Justice $20,000.00 $20,000.00 108 Monkeys $50,000.00 $50,000.00 1-A District Agricultural Association $2,000.00 $2,000.00 31heroes Projects $5,000.00 $5,000.00 350 Org $400.00 $400.00 3rd I South Asian Independent Film $10,000.00 $10,000.00 4 Paws For Ability, Inc. $250.00 $250.00 4word $5,000.00 $5,000.00 826 Michigan $1,000.00 $1,000.00 826 Valencia $17,500.00 $17,500.00 826LA $262.50 $262.50 A Foundation Building Strength Inc. $13,500.00 $13,500.00 A Future in Hope $2,000.00 $2,000.00 A Gifted Education, Inc. $1,000.00 $1,000.00 A Home Within, Inc. $200.00 $200.00 A Network for Grateful Living, Inc. $1,000.00 $1,000.00 A Place to Start $50,000.00 $50,000.00 A Safe Place, Inc. $3,500.00 $3,500.00 A Window Between Worlds $1,000.00 $1,000.00 A Wish With Wings, Inc. $3,000.00 $3,000.00 A Woman's Work, Inc. $3,500.00 $3,500.00 Grants that support SVCF's Grantee Advised Grants Total grantmaking strategies A. J. Muste Memorial Institute $400.00 $400.00 A.S.S.I.A. -

Historic Markers in Monroe County

Historic Markers in Monroe County The American Surrender - East Noble Anderson Trading Post - E. Elm, north side between N. Monroe & N. Macomb Streets The Armory Opera House - E. Second at Washington St. Boston Custer – Autie Reed - Woodland Cemetery Boy Scouts in Monroe County - E. Second & Washington St. Boyd School - Cass St. between Third & Fourth Streets Bridge School - Lewis Ave. at Dixon Rd., south side of the River Raisin British Victory at Frenchtown - North Dixie Hwy. Capture of General Winchester - Kentucky Ave. between Second & Third Streets Colonel Oliver Johnson’s Home - NE corner W. Second & Cass Streets The Custer Home - North Custer Rd. Death of Capt. Woolfolk - E. Elm Ave. between Hollywood Dr. & Riverview Ave. Death of Col. John Allen - E. Second near Winchester Deloeuil Blacksmith Shop - North Custer Rd. Doctor Eduard Dorsch - E. First St. Dr. George Francis Heath - E. Front St., north side in front of #29 Dundee – Hub of the Highways - in center of village square, Dundee Dundee’s Old Mill - Toledo Ave., Dundee, near M-50 Editor Ellis, 1825 - W. First St., north side in front of Monroe Evening News Edward D. Ellis - Ellis Library, M-50 (S. Custer Rd.) & Raisinville Rd. Edward M. Knabusch - La-Z-Boy Chair Co., Telegraph Rd. Erie and Kalamazoo Railroad - Whiteford Township Famous Waterfront - N. Dixie Hwy., near Sterling State Park entrance First Battle of the River Raisin - Hellenberg Park First District Court - E. Elm Ave., north side, east of North Dixie & railroad tracks First Presbyterian Church - SW corner First & Washington Streets Frenchtown Township - Vivian Rd., east side, north of Hurd Rd. -

Annual Education Report Statewide M-STEP Grades 3-11

01/06/2020 Annual Education Report Statewide M-STEP Grades 3-11 Subject Grade Student School State State Percent Number Percent Number Percent Number Percent Number Group Year Percent Number Advanced Advanced Proficient Proficient Partially Partially Not Not Students Students Proficient Proficient Proficient Proficient Proficient Proficient ELA 3rd Grade All 2017-18 44.4% 45,377 22.0% 22,509 22.4% 22,868 24.6% 25,162 31.0% 31,710 Content Students ELA 3rd Grade All 2018-19 45.1% 45,457 22.7% 22,858 22.4% 22,599 24.5% 24,693 30.4% 30,643 Content Students ELA 3rd Grade American 2017-18 37.8% 221 14.5% 85 23.2% 136 26.2% 153 36.1% 211 Content Indian or Alaska Native ELA 3rd Grade American 2018-19 33.9% 186 14.2% 78 19.7% 108 29.9% 164 36.2% 199 Content Indian or Alaska Native ELA 3rd Grade Asian 2017-18 64.4% 2,227 39.8% 1,377 24.6% 850 19.2% 664 16.3% 565 Content ELA 3rd Grade Asian 2018-19 64.6% 2,273 41.1% 1,448 23.4% 825 19.9% 702 15.5% 544 Content ELA 3rd Grade Black or 2017-18 19.2% 3,666 6.5% 1,243 12.7% 2,423 23.7% 4,522 57.1% 10,904 Content African American ELA 3rd Grade Black or 2018-19 19.9% 3,772 7.2% 1,362 12.7% 2,410 22.8% 4,333 57.3% 10,865 Content African American ELA 3rd Grade Hispanic of 2017-18 32.9% 2,721 13.4% 1,108 19.5% 1,613 29.1% 2,402 38.0% 3,139 Content Any Race ELA 3rd Grade Hispanic of 2018-19 34.1% 2,873 14.4% 1,213 19.7% 1,660 28.6% 2,406 37.3% 3,141 Content Any Race ELA 3rd Grade Native 2017-18 41.0% 34 15.7% 13 25.3% 21 26.5% 22 32.5% 27 Content Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander A service of the Center for -

MDE E-Rate 2019 NSLP Report

Michigan Department of Education E-Rate 2019 NSLP Report Students Annex Eligible for Total Name (DO Free Percentage Students in NOT ENTER /Reduced of Directly School District School DATA IN Meals Total Certified eligible for Percent Total Entity District NSLP % Entity COLUMNS (NSLP Students Students NSLP NSLP Number District Entity Name (Calculated) Number School Entity Name NCES Code I-N) Count) Enrolled CEP Base Year for CEP (Calculated) (Calculated) 16046621 ACE Academy (SDA) 100.00% 16046621 ACE Academy (SDA) -Glendale, Lincoln, Woodward 260094307776 224 224 224 100.00% 16046621 ACE Academy (SDA) 100.00% ACE Academy - Jefferson site 260094308800 11 11 11 100.00% 54107 AGBU Alex-Marie Manoogian School 58.96% 54107 AGBU Alex-Marie Manoogian School 260010600688 237 402 237 58.96% 16071890 Academic and Career Education Academy 78.36% 16071890 Academic and Career Education Academy 260033004509 105 134 105 78.36% 54366 Academy for Business and Technology 100.00% 16057019 Academy for Business and Technology Elementary 260016601667 255 264 2019 79.50% 264 100.00% 54366 Academy for Business and Technology 100.00% 54366 Academy for Business and Technology High School 260016601035 226 259 2019 79.50% 259 100.00% 16039853 Academy of Warren 100.00% 16039853 Academy of Warren 260030801884 636 652 2019 85.45% 652 100.00% 16058986 Achieve Charter Academy 15.34% 16058986 Achieve Charter Academy 260096307974 118 769 118 15.34% 131790 Adams Township School District 54.34% 58616 Jeffers High School 260189003921 130 250 130 52.00% 131790 Adams Township -

Very Simplified All Schools Ranked

Top to Bottom List of all Schools Determined by mathematics and English language arts achievement and improvement scores 6/23/2010 Statewide combined math/ELA achievement/improve ment percentile District Name Building Name ranking Forest Hills Public Schools Eastern Middle School 100.0 Detroit City School District Cooley North Wing 99.9 Detroit City School District Kettering West Wing 99.9 Grand Rapids Public Schools City Middle/High School 99.9 Forest Hills Public Schools Northern Hills Middle School 99.8 Bloomfield Hills School District Conant Elementary School 99.8 Saginaw City School District Saginaw Arts and Sciences Academy 99.8 Livonia Public Schools Holmes Middle School 99.7 Okemos Public Schools Kinawa Middle School 99.7 Grand Blanc Community Schools City School 99.7 Birmingham City School District Birmingham Covington School 99.6 Forest Hills Public Schools Ada Vista Elementary School 99.6 Homer Community Schools Homer Middle School 99.6 North Muskegon Public Schools North Muskegon High School 99.5 Novi Community School District Novi Middle School 99.5 Forest Hills Public Schools Central Middle School 99.5 Livonia Public Schools Webster Elementary School 99.4 DeWitt Public Schools DeWitt Junior High School 99.4 Forest Hills Public Schools Northern Trails 5/6 School 99.4 East Grand Rapids Public Schools East Grand Rapids Middle School 99.3 Okemos Public Schools Okemos High School 99.3 Houghton-Portage Township Schools Houghton Central High School 99.2 Utica Community Schools Eisenhower High School 99.2 Okemos Public Schools Chippewa -

Michigan Department of Community Health Mercury-Free Schools in Michigan

Michigan Department of Community Health Mercury-Free Schools in Michigan Entity Name City Eastside Middle School Bay City Trinity Lutheran School St. Joseph A.D. Johnston Jr/Sr High School Bessemer Abbot School Ann Arbor Abbott Middle School West Bloomfield Academic Transitional Academy Port Huron Academy for Business and Technology Elementary Dearborn Ada Christian School Ada Ada Vista Elementary Ada Adams Christian School Wyoming Adams Elementary School Bad Axe Adams Middle School Westland Adlai Stevenson Middle School Westland Adrian High School Adrian Adrian Middle School 5/6 Building Adrian Adrian Middle School 7/8 Building Adrian Airport Senior High School Carleton Akiva Hebrew Day School Southfield Akron-Fairgrove Elem. School Akron Akron-Fairgrove Jr/Sr High School Fairgrove Alaiedon Elementary School Mason Alamo Elementary School Kalamazoo Albee Elementary School Burt Albert Schweitzer Elementary School Westland Alcona Elementary School Lincoln Alcona Middle School Lincoln Alexander Elementary School Adrian Alexander Hamilton Elementary School Westland All Saints Catholic School Alpena Allegan High School Allegan Allegan Street Elementary School Otsego Allen Elementary School Southgate Allendale Christian School Allendale Allendale High School Allendale Allendale Middle School Allendale Alma Middle School Alma Alma Senior High School Alma Almont Middle School Almont Alpena High School Alpena Alward Elementary School Hudsonville Amberly Elementary School Portage Amerman Elementary School Northville Anchor Bay High School Fair Haven Anchor Bay Middle School North New Baltimore Anderson Elementary School Bronson Anderson Middle School Berkley Andrew G. Schmidt Middle School Fenton Andrews Elementary School Three Rivers Angell School Ann Arbor Angelou, Maya Elementary School Detroit Angling Road Elementary School Portage Angus Elementary School Sterling Heights Ann Arbor Open at Mack School Ann Arbor Ann J.