Michig a N Educ a T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master Plan 2017

RAAIISSIINNVVIILLLLEE TOOWWNNSSHHIIPP R T Approved and Adopted MM AASSTTEERR PPLLAANN March 3, 20 14 Adopted September 18, 2017 The Raisinville Township Planning Commission approves this Master Plan as a guide for the future development of the Township John Delmotte Planning Commission Chair September 18, 2017 Page 2 Adopted September 18, 2017 | RAISINVILLE TOWNSHIP Master Plan A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS Township Board Gerald Blanchette, Supervisor Brenda Fetterly, Clerk Rose Marie Meyer, Treasurer Keith Henderson, Trustee Thomas Woelmer, Trustee Planning Commission John Delmotte, Chair Michael Jaworski, Vice-Chair Ann Nickel-Swinkey, Secretary Craig Assenmacher, Commissioner Kevin Kruskie, Commissioner Gary Nowitzke, Commissioner Thomas Woelmer, Board Representative Prepared by: Assisted by: The Mannik & Smith Group, Inc. RAISINVILLE TOWNSHIP Master Plan | Adopted September 18, 2017 Page i This page intentionally left blank Page ii Adopted September 18, 2017 | RAISINVILLE TOWNSHIP Master Plan C ONTENTS I NTRODUCTION Purpose and Legislative Authority of the Master Plan ........................................... 1 How the Plan Is to Be Used ................................................................................... 2 Plan Update ........................................................................................................... 2 Planning Process ................................................................................................... 2 Plan Organization.................................................................................................. -

Center for Educational Performance and Information (CEPI)

Center for Educational Performance and Information (CEPI) State of Michigan 2010 Cohort 4-Year & 2009 Cohort 5-Year Graduation and Dropout Rate Reports Questions? Contact: 517.335.0505 e-mail: [email protected] Table of Contents Documentation Overview of Michigan’s Cohort Graduation and Dropout Rates ............................................................. 3 2010 Cohort Four-Year Graduation Rate ............................................................................................... 3 2010 Cohort Four-Year Dropout Rate .................................................................................................... 4 Reading the 2010 Cohort Four-Year Graduation and Dropout Rate Report ........................................... 4 2009 Cohort Five-Year Graduation and Dropout Rates .......................................................................... 5 Reading the 2009 Cohort Five-Year Graduation and Dropout Rate Report ............................................ 5 Data Validation and Appeals Process .................................................................................................... 6 Reports 2010 Cohort Four-Year Graduation and Dropout Rates for the State of Michigan………………………...7 2010 Cohort Four-Year Graduation and Dropout Rates for Local Education Agency (LEA) ................... 7 2010 Cohort Four-Year Graduation and Dropout Rates for Public School Academy (PSA) ................. 52 2010 Cohort Four-Year Dropout Rates for Intermediate School District (ISD) ..................................... -

Articulation Agreements: College of Applied Technologies Updated: December 1, 2018

Articulation Agreements: College of Applied Technologies Updated: December 1, 2018 Connecticut A.I. Prince Tech. HS CT Automotive Bullard-Havens Tech. HS CT Automotive HVAC E.C. Goodwin Technical High School CT Automotive HVAC Eli Whitney Technical HS CT Automotive Emmett O'Brien Tech High School CT Automotive HVAC Grasso Southeastern Tech HS CT Automotive H.C. Wilcox Technical High School CT Automotive HVAC H.H. Ellis Tech H.S. CT MLR Henry Abbot Tech. HS CT Automotive HVAC Howell Cheney Tech HS CT Automotive HVAC J M Wright Technical High School CT Automotive Norwich Technical High School CT Automotive HVAC Oliver Wolcott Tech HS CT Automotive Platt Technical High School CT Automotive HVAC Vinal Technical High School CT Automotive HVAC W F Kaynor Technical High School CT Automotive Windham Technical High School CT MLR HVAC Delaware Delcastle Tech High School DE HVAC Dover High School DE Automotive Howard High School Technology DE Automotive HVAC Paul Hodgson Voc-Tech High School DE Automotive Polytech High School DE Automotive St. Georges Technical High School DE Automotive HVAC Sussex Technical High School DE Automotive HVAC Florida Charlotte Co. Vo-Tech FL Automotive Crestview Senior High School FL MLR Eau Gallie High School FL MLR First Coast Tech Inst FL Automotive Frank H Peterson Acad Tech FL Automotive Heritage High School FL Automotive Hernando High School FL Automotive Kathleen Senior High School FL Automotive Lively Area Voc-Tech Center FL Automotive Loften High School FL MLR Merritt Island High School FL MLR Middleburg High -

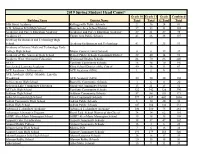

2019 Spring Student Head Count*

2019 Spring Student Head Count* Grade 10 Grade 11 Grade Combined Building Name District Name Total Total 12 Total Total 54th Street Academy Kelloggsville Public Schools 21 36 24 81 A.D. Johnston Jr/Sr High School Bessemer Area School District 39 33 31 103 Academic and Career Education Academy Academic and Career Education Academy 27 21 27 75 Academy 21 Center Line Public Schools 43 26 38 107 Academy for Business and Technology High School Academy for Business and Technology 41 17 35 93 Academy of Science Math and Technology Early College High School Mason County Central Schools 0 0 39 39 Academy of The Americas High School Detroit Public Schools Community District 39 40 14 93 Academy West Alternative Education Westwood Heights Schools 84 70 86 240 ACCE Ypsilanti Community Schools 28 48 70 146 Accelerated Learning Academy Flint, School District of the City of 40 16 11 67 ACE Academy - Jefferson site ACE Academy (SDA) 1 2 0 3 ACE Academy (SDA) -Glendale, Lincoln, Woodward ACE Academy (SDA) 50 50 30 130 Achievement High School Roseville Community Schools 3 6 11 20 Ackerson Lake Community Education Napoleon Community Schools 15 21 15 51 ACTech High School Ypsilanti Community Schools 122 142 126 390 Addison High School Addison Community Schools 57 54 60 171 Adlai Stevenson High School Utica Community Schools 597 637 602 1836 Adrian Community High School Adrian Public Schools 6 10 20 36 Adrian High School Adrian Public Schools 187 184 180 551 Advanced Technology Academy Advanced Technology Academy 106 100 75 281 Advantage Alternative Program -

Program to Recognize Excellence in Student Literary Magazines, 1985. Ranked Magazines. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 265 562 CS 209 541 AUTHOR Gibbs, Sandra E., Comp. TITLE Program to Recognize Excellence in Student Literary Magazines, 1985. Ranked Magazines. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, PUB DATE Mar 86 NOTE 88p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - General (130) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Awards; Creative Writing; Evaluation Criteria; Layout (Publications); Periodicals; Secondary Education; *Student Publications; Writing Evaluation IDENTIFIERS Contests; Excellence in Education; *Literary Magazines; National Council of Teachers of English ABSTRACT In keeping with efforts of the National Council of Teachers of English to promote and recognize excellence in writing in the schools, this booklet presents the rankings of winning entries in the second year of NCTE's Program to Recognize Excellence in Student Literary Magazines in American and Canadian schools, and American schools abroad. Following an introduction detailing the evaluation process and criteria, the magazines are listed by state or country, and subdivided by superior, excellent, or aboveaverage rankings. Those superior magazines which received the program's highest award in a second evaluation are also listed. Each entry includes the school address, student editor(s), faculty advisor, and cost of the magazine. (HTH) ***********************************************w*********************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best thatcan be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** National Council of Teachers of English 1111 Kenyon Road. Urbana. Illinois 61801 Programto Recognize Excellence " in Student LiteraryMagazines UJ 1985 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) Vitusdocument has been reproduced as roomed from the person or organization originating it 0 Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction Quality. -

Robert Griffin

ROBERT GRIFFIN Interviewed by Dennis Cawthorne July 25, 1996 Sponsored by the Michigan Political History Society P.O. Box 4684 East Lansing, MI 48826-4684 Transcript: MPHS Oral History of Robert P. Griffin, interviewed by Dennis Cawthorne, July 1996 This interview is part of the James J. Blanchard Living Library of Michigan Political History. Dennis Cawthorne (DC): Robert P. Griffin has had an exciting and remarkable political career that has spanned nearly 40 years of Michigan and American political history: United States Representative, United States Senator, author of major legislation, confidant of Presidents, Supreme Court Justice of the Michigan Supreme Court. He has been all of these things and more. DC: RG was born in Detroit, grew up in Garden City, and graduated from Dearborn Fordson High School. He served 14 months in the Infantry in World War II in Europe. After the war, he graduated from Central Michigan University, and the University of Michigan Law School. DC: Bob, what was the spark that caused you to get interested and excited about politics? Robert Griffin (RG): Well, like you and a lot of others, I know here and there, in junior high or someplace, I was perhaps a class president or a student council president or something of that kind, but I don't think I really became interested until I went to the Wolverine Boys' State, between the junior and senior year I had at Fordson High School. There, somehow, things seemed to come together. I was a candidate for governor, but I didn't have the support, so a deal was made, and I ran for the lieutenant governor and was elected and spent the day, as these young people do every year, in the legislative chambers in Lansing. -

An Occupational Study of the Graduates of the Fordson High School

lll‘ I I l l lit I I | ;| i f ‘ ' ‘31 'H i |‘' ' 1mm .HNA _mmm AN OCCUPATIONAL STUDY OF THE GMEWES OF THE FDRDSUN HlGH SCENE. DEARBDRN, Mia-23:3. ii THESiS fDR THE DEGREE OF M. A STANLEY 8. SMITH W32 S‘L ' I.....‘ .t‘lul‘ll‘llr THESIS A THESIS BASED UPON AN OCJUPATIOHAL STUDY OF THE GRADUATES " OF THE FORDSOH HIGH SCHOOL DEARBCRN , iISHiGAN Submitted as Partial Fulfillment of the Recuirements For the Degree of Easter of Arts Michigan State College July 1952 By Stanley S. Snith THESlS CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ............................................ .1 The Purpose and Nature of the Study ................. l The Method of the Study ............................. 5, THE COMNUNITY ............................................ 9 The City of Dearcorn ................................ 9 The City of Detroit ................................ 11 E nployznent Conditions in Detroit from 1925-31 ...... 13 THE SCHOOLS OF DEARBORN. ................................ 16 The Fordson Public Schools ......................... 18 ' The Fordson High School ............................ 17 Vocational Guidance in the Fordson High School ..... 20 The Fordson High School Placement Service .......... 21 The Henry Ford Trade School ........................ 23 FACTORS INFLUENCING GRADUATES' CHOICE OF AN OCCUPATION..29 Nativity of the Graduates and their Parents ........ 31 Present Occupations of the Graduates and their Fathers ....................................... 35 The Choice of an Occupation ........................ 4O OCCUPATIONAL DISTRIBUTION OF GRADUATES BY -

Dearborn Federation of Teachers Local 681 Records 37.75 Linear Feet (37 SB, 2 MB) 1939-1995, Bulk 1960S-1980S

Dearborn Federation of Teachers Local 681 Records 37.75 linear feet (37 SB, 2 MB) 1939-1995, bulk 1960s-1980s Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI Finding aid written by Jennifer Meekhof on March 19, 2012 Accession Number: LR001794 Creator: Dearborn Federation of Teachers Local 681 Acquisition: The records of the Dearborn Federation of Teachers were deposited at the Reuther Library in October 2002. Language: Material entirely in English. Access: Collection is open for research. Use: Refer to the Walter P. Reuther Library Rules for Use of Archival Materials. Restrictions: Researchers may encounter records of a sensitive nature – personnel files, case records and those involving investigations, legal and other private matters. Privacy laws and restrictions imposed by the Library prohibit the use of names and other personal information which might identify an individual, except with written permission from the Director and/or the donor. Notes: Citation style: “Dearborn Federation of Teachers Local 681 Records, Box [#], Folder [#], Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University” Related Material: Michigan Federation of Teachers Records Photograph negatives, audiocassette tapes and B&W slides (Box 39) have been transferred to the Archives Audiovisual Department. PLEASE NOTE: Material in this collection has been arranged by series ONLY. Folders are not arranged within each series – we have provided an inventory based on their original order. Subjects may be dispersed throughout several boxes within any given series. Abstract Part of the national American Federation of Teachers and statewide Michigan Federation of Teachers, the Dearborn Federation of Teachers, was chartered on February 28, 1945. Twenty years later, in1965, Michigan passed the Public Employee Relations Act; a law making organization and collective bargaining legal for public employees. -

Arab Stereotypes and American Educators

Arab Stereotypes and American Educators by Marvin Wingfield and Bushra Karaman When American children hear the word "Arab," what is the first thing that often comes to mind? It might well be the Arabian Nights fantasy imagery in the Disney film "Aladdin," a film which has been very popular in theaters and on video and is sometimes shown in school classrooms. Yet Arab Americans have problems with this film. Although in many ways it is charming, artistically impressive and one of the few American films to feature an Arab hero or heroine, a closer look reveals some disturbing features. The film's light-skinned lead characters, Aladdin and Jasmine, have Anglicized features and Anglo American accents. This is in contrast to the other characters who are dark-skinned, swarthy and villainous - cruel palace guards or greedy merchants with "Arabic" accents and grotesque facial features. The film's opening song sets the tone: Oh, I come from a land, From a faraway place Where the caravan camels roam. Where they cut off your ear If they don't like your face. It's barbaric, but hey, it's home. Thus the film immediately characterizes the Arab world as alien, exotic and “other.” Arab Americans see this film as perpetuating the tired stereotype of the Arab world as a place of deserts and camels, of arbitrary cruelty and barbarism. Therefore, Arab Americans raised a cry of protest regarding “Aladdin.” The American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC) challenged Disney and persuaded the studio to change a phrase in the lyrics for the video version of the film to say: “It's flat and immense, and the heat is intense. -

2013 Annual Report VISION CCESS Strives to Enable and Empower Individuals, Families and a Communities to Lead Informed, Productive and Culturally Sensitive Lives

2013 Annual Report VISION CCESS strives to enable and empower individuals, families and A communities to lead informed, productive and culturally sensitive lives. As a nonprofit model of excellence, we honor our Arab American heritage through community-building and service to all those in need, of every heritage. ACCESS is a strong advocate for cultural and social entrepreneurship imbued with the values of community service, healthy lifestyles, education and philanthropy. 2 / 2013 Annual Report Contents 2 4 OVERVIEW BOARD 6 38 DEPARTMENTS STATISTICAL REPORT 40 42 TREASURER’S REPORT DONORS / 2013 Annual Report 1 A MESSAGE FROM OUR LEADERS Hassan Jaber Wadad Abed Executive Director President PASSION TO SERVE. PASSION TO SUCCEED. PASSION FOR FAIRNESS AND JUSTICE. PASSION TO IMPROVE THE LIVES OF OTHERS. assion” describes the daily work by ACCESS staff members who ACCESS greatly improved in the areas of technology, human “P are determined to stand and work as a team in their efforts to create resources, and development. successful, happy and productive communities. In addition to our nearly 100 traditional programs that cover the It is that ferocity and passion that has given us great achievements this whole gamut of social, economic, health and educational programs, year. With ACCESS as a stronger institution, we can do more to assist, we also launched new innovative initiatives including ACCESS Growth improve and empower others; and work stronger as advocates on the local Center and Welcome Mat Detroit. and national levels for Arab American communities and all whom we serve. Welcome Mat Detroit, in partnership with Global Detroit, is a We made significant improvements in building our capacity to major initiative led by ACCESS and funded through the W.K. -

Grantee Advised Grants Grants That Support SVCF's Grantmaking Strategies Total 10 Books a Home $256,500.00 $256,500.00 10,000 De

Grants that support SVCF's Grantee Advised Grants Total grantmaking strategies 10 Books A Home $256,500.00 $256,500.00 10,000 Degrees $5,000.00 $5,000.00 100 Women Charitable Foundation, Inc. $1,500.00 $1,500.00 1000 Friends of Oregon $1,500.00 $1,500.00 10000 Cries for Justice $20,000.00 $20,000.00 108 Monkeys $50,000.00 $50,000.00 1-A District Agricultural Association $2,000.00 $2,000.00 31heroes Projects $5,000.00 $5,000.00 350 Org $400.00 $400.00 3rd I South Asian Independent Film $10,000.00 $10,000.00 4 Paws For Ability, Inc. $250.00 $250.00 4word $5,000.00 $5,000.00 826 Michigan $1,000.00 $1,000.00 826 Valencia $17,500.00 $17,500.00 826LA $262.50 $262.50 A Foundation Building Strength Inc. $13,500.00 $13,500.00 A Future in Hope $2,000.00 $2,000.00 A Gifted Education, Inc. $1,000.00 $1,000.00 A Home Within, Inc. $200.00 $200.00 A Network for Grateful Living, Inc. $1,000.00 $1,000.00 A Place to Start $50,000.00 $50,000.00 A Safe Place, Inc. $3,500.00 $3,500.00 A Window Between Worlds $1,000.00 $1,000.00 A Wish With Wings, Inc. $3,000.00 $3,000.00 A Woman's Work, Inc. $3,500.00 $3,500.00 Grants that support SVCF's Grantee Advised Grants Total grantmaking strategies A. J. Muste Memorial Institute $400.00 $400.00 A.S.S.I.A. -

Student Code of Conduct

Student Code of Conduct Responsibilities and Rights Dearborn Public Schools Dearborn, Michigan Dearborn Board of Education Joseph A. Guido, President Aimee Blackburn, Vice President Darrell Donelson, Secretary James H. Schoolmaster, Treasurer Mary Lane, Trustee Mary Petlichkoff, Trustee Pamela L. Adams, Trustee Superintendent of Schools Brian Whiston 2008 CODE OF CONDUCT COMMITTEE MEMBERS Marc A. Zigterman........................................................ Co-Chair-Coordinator, Student Services Dr. Kenneth K. Ayouby ................. Co-Chair-Administrative Hearing Officer, Student Services Heyam Alcodray ....................................................... Assistant Principal, Dearborn High School William Ali............................................Youth Intervention Facilitator, Edsel Ford High School Charles Baughman ..................................................Assistant Principal, Edsel Ford High School Oussama Baydoun....................................................... Assistant Principal, Fordson High School Tahsine Bazzi.....................................................Student Services Liaison, Fordson High School Patti Buoy.............................................................................Principal, Haigh Elementary School Angela Burley ...............................................School Social Worker, O. L. Smith Middle School Scott Casebolt.............................................................. Assistant Principal, Fordson High School Danene Charles ...............................................................