Cass Corridor Documentation Project Oral History Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Add To), Provided That Credit Is Given to Michael Erlewine for Any Use of the Data Enclosed Here

POSTER DATA COMPILED BY MICHAEL ERLEWINE Copyright © 2003-2020 by Michael Erlewine THIS DATA IS FREE TO USE, SHARE, (AND ADD TO), PROVIDED THAT CREDIT IS GIVEN TO MICHAEL ERLEWINE FOR ANY USE OF THE DATA ENCLOSED HERE. There is no guarantee that this data is complete or without errors and typos. This is just a beginning to document this important field of study. [email protected] ------------------------------ P --------- / CP060727 / CP060727 20th Anniversary Notes: The original art, done by Gary Grimshaw for ArtRock Gallery, in San Francisco Benefit: First American Tour 1969 Artist: Gary Grimshaw Promoter: Artrock Items: Original poster / CP060727 / CP060727 (11 x 17) Performers: : Led Zeppelin ------------------------------ GBR-G/G 1966 T-1 --------- 1966 / GBR G/G CP010035 / CS05131 Free Ticket for Grande Ballroom Notes: Grande Free Pass The "Good for One Free Trip at the Grande" pass has more than passing meaning. It was the key to distributing the Grande postcards on the street and in schools. Volunteers, mostly high-school-aged kids, would get a stack of cards to pass out, plus a free pass to the Grande for themselves. Russ Gibb, who ran the Grande Ballroom, says that this was the ticket, so to speak, to bring in the crowds. While posters in Detroit did not have the effect that posters in San Francisco had, and handbills were only somewhat better, the cards turned out to actually work best. These cards are quite rare. Artist: Gary Grimshaw Venue: Grande Ballroom Promoter: Russ Gibb Presents Items: Ticket GBR-G/G Edition 1 / CP010035 / CS05131 Performers: 1966: Grande Ballroom ------------------------------ GBR-G/G P-01 (H-01) 1966-10-07 P-1 -- ------- 1966-10-07 / GBR G/G P-01 (H-01) CP007394 / CP02638 MC5, Chosen Few at Grande Ballroom - Detroit, MI Notes: Not the very rarest (they are at lest 12, perhaps as 15-16 known copies), but this is the first poster in the series, and considered more or less essential. -

Articulation Agreements: College of Applied Technologies Updated: December 1, 2018

Articulation Agreements: College of Applied Technologies Updated: December 1, 2018 Connecticut A.I. Prince Tech. HS CT Automotive Bullard-Havens Tech. HS CT Automotive HVAC E.C. Goodwin Technical High School CT Automotive HVAC Eli Whitney Technical HS CT Automotive Emmett O'Brien Tech High School CT Automotive HVAC Grasso Southeastern Tech HS CT Automotive H.C. Wilcox Technical High School CT Automotive HVAC H.H. Ellis Tech H.S. CT MLR Henry Abbot Tech. HS CT Automotive HVAC Howell Cheney Tech HS CT Automotive HVAC J M Wright Technical High School CT Automotive Norwich Technical High School CT Automotive HVAC Oliver Wolcott Tech HS CT Automotive Platt Technical High School CT Automotive HVAC Vinal Technical High School CT Automotive HVAC W F Kaynor Technical High School CT Automotive Windham Technical High School CT MLR HVAC Delaware Delcastle Tech High School DE HVAC Dover High School DE Automotive Howard High School Technology DE Automotive HVAC Paul Hodgson Voc-Tech High School DE Automotive Polytech High School DE Automotive St. Georges Technical High School DE Automotive HVAC Sussex Technical High School DE Automotive HVAC Florida Charlotte Co. Vo-Tech FL Automotive Crestview Senior High School FL MLR Eau Gallie High School FL MLR First Coast Tech Inst FL Automotive Frank H Peterson Acad Tech FL Automotive Heritage High School FL Automotive Hernando High School FL Automotive Kathleen Senior High School FL Automotive Lively Area Voc-Tech Center FL Automotive Loften High School FL MLR Merritt Island High School FL MLR Middleburg High -

Michig a N Educ a T

2019 MICHIGAN EDUCATION FALL THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN SCHOOL OF EDUCATION 2 Bastedo helped to develop Landscape, a tool that provides context about the opportunities that applicants have—or do not have—in their communities and high schools. His ongoing research informs college admissions practices and strategies, and will reveal the role that Landscape plays in efforts of colleges to admit a diverse freshman class. The newly launched TeachingWorks Resource Library supports teacher educa- tors with free, high-quality curriculum materials. We follow the researchers and FALL 2019 FALL product designers through their use of the design thinking process to discover • how they developed and refined the Resource Library and how it is being used. As educators, we empower students to be innovators. Ninth graders at The School at Marygrove, which we opened this fall in partnership with the Detroit Public Schools Community District, are taking Introduction to Human Centered Design and Engineering at their new school in northwest Detroit. Taught by the first “resident” of the Teaching School, Ms. Sneha Rathi, the curriculum was co-developed with a team of graduate students, staff, and faculty from the SOE. Students in Rathi’s class are learning how they can use design thinking to address challenges or needs in their community. I am proud of these young students; our teacher education graduate, Sneha Rathi; our graduate students; and our faculty and staff who are working together to build and study innovative education opportunities. Their work gives us all hope and inspiration. We also began work with the first cohort of Dow Innovation Teacher Fellows MICHIGAN EDUCATION EDUCATION MICHIGAN Dean Elizabeth Birr Moje at the SOE homecoming tailgate, October 5, 2019. -

Program to Recognize Excellence in Student Literary Magazines, 1985. Ranked Magazines. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 265 562 CS 209 541 AUTHOR Gibbs, Sandra E., Comp. TITLE Program to Recognize Excellence in Student Literary Magazines, 1985. Ranked Magazines. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, PUB DATE Mar 86 NOTE 88p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - General (130) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Awards; Creative Writing; Evaluation Criteria; Layout (Publications); Periodicals; Secondary Education; *Student Publications; Writing Evaluation IDENTIFIERS Contests; Excellence in Education; *Literary Magazines; National Council of Teachers of English ABSTRACT In keeping with efforts of the National Council of Teachers of English to promote and recognize excellence in writing in the schools, this booklet presents the rankings of winning entries in the second year of NCTE's Program to Recognize Excellence in Student Literary Magazines in American and Canadian schools, and American schools abroad. Following an introduction detailing the evaluation process and criteria, the magazines are listed by state or country, and subdivided by superior, excellent, or aboveaverage rankings. Those superior magazines which received the program's highest award in a second evaluation are also listed. Each entry includes the school address, student editor(s), faculty advisor, and cost of the magazine. (HTH) ***********************************************w*********************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best thatcan be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** National Council of Teachers of English 1111 Kenyon Road. Urbana. Illinois 61801 Programto Recognize Excellence " in Student LiteraryMagazines UJ 1985 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) Vitusdocument has been reproduced as roomed from the person or organization originating it 0 Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction Quality. -

DKT/MC5 Sonic Revolution

Listen mister, back in my day, blotter was 25 cents a hit and we had to walk two miles uphill to get it! And we liked it! Wayne Kramer is not someone who normally seems into beaming—his image is a little more ferocious than that. But onstage during the second night of the DKT-MC5 tour in Chicago, Kramer busted loose a big fat grin and started jumping up and down at one point. Back in the MC5 days, the band was known for its energetic, physical shows. Having never seen them live, I don't know if they ever jumped for pure joy back then, but that's clearly what Kramer was doing that night. The reunion of the surviving members of the MC5 (guitarist Kramer, bassist Michael Davis and drummer Dennis Thompson)—along with resurrections of the Stooges and the New York Dolls—is showing a renewed interest in these progenitors of punk rock. "It's surprising to me and it should be surprising to Iggy and those guys how much influence and affect our two bands have had on music now," Davis said. "I'm kind of in awe of it. We've had this kind of effect. And it's one thing to do something that people DKT/MC5 admire a lot, and go, 'That was really cool Sonic Revolution: Live At London's 100 stuff,' but to have this much influence is really Club [DVD] surprising to me." 2004 Image He continued: "I thought it was great, but I The DKT/MC5 gig at London's 100 Club never thought it was so foundational to the was the first salvo in what has become a future. -

Robert Griffin

ROBERT GRIFFIN Interviewed by Dennis Cawthorne July 25, 1996 Sponsored by the Michigan Political History Society P.O. Box 4684 East Lansing, MI 48826-4684 Transcript: MPHS Oral History of Robert P. Griffin, interviewed by Dennis Cawthorne, July 1996 This interview is part of the James J. Blanchard Living Library of Michigan Political History. Dennis Cawthorne (DC): Robert P. Griffin has had an exciting and remarkable political career that has spanned nearly 40 years of Michigan and American political history: United States Representative, United States Senator, author of major legislation, confidant of Presidents, Supreme Court Justice of the Michigan Supreme Court. He has been all of these things and more. DC: RG was born in Detroit, grew up in Garden City, and graduated from Dearborn Fordson High School. He served 14 months in the Infantry in World War II in Europe. After the war, he graduated from Central Michigan University, and the University of Michigan Law School. DC: Bob, what was the spark that caused you to get interested and excited about politics? Robert Griffin (RG): Well, like you and a lot of others, I know here and there, in junior high or someplace, I was perhaps a class president or a student council president or something of that kind, but I don't think I really became interested until I went to the Wolverine Boys' State, between the junior and senior year I had at Fordson High School. There, somehow, things seemed to come together. I was a candidate for governor, but I didn't have the support, so a deal was made, and I ran for the lieutenant governor and was elected and spent the day, as these young people do every year, in the legislative chambers in Lansing. -

An Occupational Study of the Graduates of the Fordson High School

lll‘ I I l l lit I I | ;| i f ‘ ' ‘31 'H i |‘' ' 1mm .HNA _mmm AN OCCUPATIONAL STUDY OF THE GMEWES OF THE FDRDSUN HlGH SCENE. DEARBDRN, Mia-23:3. ii THESiS fDR THE DEGREE OF M. A STANLEY 8. SMITH W32 S‘L ' I.....‘ .t‘lul‘ll‘llr THESIS A THESIS BASED UPON AN OCJUPATIOHAL STUDY OF THE GRADUATES " OF THE FORDSOH HIGH SCHOOL DEARBCRN , iISHiGAN Submitted as Partial Fulfillment of the Recuirements For the Degree of Easter of Arts Michigan State College July 1952 By Stanley S. Snith THESlS CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ............................................ .1 The Purpose and Nature of the Study ................. l The Method of the Study ............................. 5, THE COMNUNITY ............................................ 9 The City of Dearcorn ................................ 9 The City of Detroit ................................ 11 E nployznent Conditions in Detroit from 1925-31 ...... 13 THE SCHOOLS OF DEARBORN. ................................ 16 The Fordson Public Schools ......................... 18 ' The Fordson High School ............................ 17 Vocational Guidance in the Fordson High School ..... 20 The Fordson High School Placement Service .......... 21 The Henry Ford Trade School ........................ 23 FACTORS INFLUENCING GRADUATES' CHOICE OF AN OCCUPATION..29 Nativity of the Graduates and their Parents ........ 31 Present Occupations of the Graduates and their Fathers ....................................... 35 The Choice of an Occupation ........................ 4O OCCUPATIONAL DISTRIBUTION OF GRADUATES BY -

Dearborn Federation of Teachers Local 681 Records 37.75 Linear Feet (37 SB, 2 MB) 1939-1995, Bulk 1960S-1980S

Dearborn Federation of Teachers Local 681 Records 37.75 linear feet (37 SB, 2 MB) 1939-1995, bulk 1960s-1980s Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI Finding aid written by Jennifer Meekhof on March 19, 2012 Accession Number: LR001794 Creator: Dearborn Federation of Teachers Local 681 Acquisition: The records of the Dearborn Federation of Teachers were deposited at the Reuther Library in October 2002. Language: Material entirely in English. Access: Collection is open for research. Use: Refer to the Walter P. Reuther Library Rules for Use of Archival Materials. Restrictions: Researchers may encounter records of a sensitive nature – personnel files, case records and those involving investigations, legal and other private matters. Privacy laws and restrictions imposed by the Library prohibit the use of names and other personal information which might identify an individual, except with written permission from the Director and/or the donor. Notes: Citation style: “Dearborn Federation of Teachers Local 681 Records, Box [#], Folder [#], Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University” Related Material: Michigan Federation of Teachers Records Photograph negatives, audiocassette tapes and B&W slides (Box 39) have been transferred to the Archives Audiovisual Department. PLEASE NOTE: Material in this collection has been arranged by series ONLY. Folders are not arranged within each series – we have provided an inventory based on their original order. Subjects may be dispersed throughout several boxes within any given series. Abstract Part of the national American Federation of Teachers and statewide Michigan Federation of Teachers, the Dearborn Federation of Teachers, was chartered on February 28, 1945. Twenty years later, in1965, Michigan passed the Public Employee Relations Act; a law making organization and collective bargaining legal for public employees. -

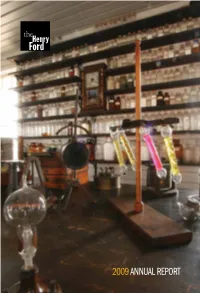

2009Annual Report

2009 Annual Report The only true test of values, either of men or of things, is that of their ability to make the world a better place in which to live. – Henry Ford Welcome and thanks from the chairman and the president For our region, our state, our country and the world, the year 2009 was one marked by great economic upheaval. Here in Southeast Michigan, it was felt in particularly profound ways, as we experienced historic and momentous change in what, for decades, had been our primary industrial base and the source of our global reputation. The impact on the American automotive industry was equaled, if not eclipsed, by a near-meltdown in the world’s financial markets. Throughout the country, it was a year of incredible challenge for our industries, our government, our institutions and our families. In such challenging times, institutions — particularly cultural institutions like The Henry Ford — become all the more important. In 2009, more than 1.6 million people were drawn to our campus, roughly 100,000 more than we had averaged during the previous several years. Why, in a time of such severe economic strain, did an increased number of people choose to spend time and discretionary resources visiting an American history complex? We believe the answer lies in The Henry Ford’s unique offerings; namely, the opportunity for families to immerse themselves in the optimism that infuses the stories of American innovation, ingenuity and resourcefulness that we present. They are traits that have successfully led us through the toughest and most challenging moments in our history. -

Arab Stereotypes and American Educators

Arab Stereotypes and American Educators by Marvin Wingfield and Bushra Karaman When American children hear the word "Arab," what is the first thing that often comes to mind? It might well be the Arabian Nights fantasy imagery in the Disney film "Aladdin," a film which has been very popular in theaters and on video and is sometimes shown in school classrooms. Yet Arab Americans have problems with this film. Although in many ways it is charming, artistically impressive and one of the few American films to feature an Arab hero or heroine, a closer look reveals some disturbing features. The film's light-skinned lead characters, Aladdin and Jasmine, have Anglicized features and Anglo American accents. This is in contrast to the other characters who are dark-skinned, swarthy and villainous - cruel palace guards or greedy merchants with "Arabic" accents and grotesque facial features. The film's opening song sets the tone: Oh, I come from a land, From a faraway place Where the caravan camels roam. Where they cut off your ear If they don't like your face. It's barbaric, but hey, it's home. Thus the film immediately characterizes the Arab world as alien, exotic and “other.” Arab Americans see this film as perpetuating the tired stereotype of the Arab world as a place of deserts and camels, of arbitrary cruelty and barbarism. Therefore, Arab Americans raised a cry of protest regarding “Aladdin.” The American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC) challenged Disney and persuaded the studio to change a phrase in the lyrics for the video version of the film to say: “It's flat and immense, and the heat is intense. -

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI Via AP Balazs Mohai

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI via AP Balazs Mohai Sziget Festival March 26-April 2 Horizon Festival Arinsal, Andorra Web www.horizonfestival.net Artists Floating Points, Motor City Drum Ensemble, Ben UFO, Oneman, Kink, Mala, AJ Tracey, Midland, Craig Charles, Romare, Mumdance, Yussef Kamaal, OM Unit, Riot Jazz, Icicle, Jasper James, Josey Rebelle, Dan Shake, Avalon Emerson, Rockwell, Channel One, Hybrid Minds, Jam Baxter, Technimatic, Cooly G, Courtesy, Eva Lazarus, Marc Pinol, DJ Fra, Guim Lebowski, Scott Garcia, OR:LA, EL-B, Moony, Wayward, Nick Nikolov, Jamie Rodigan, Bahia Haze, Emerald, Sammy B-Side, Etch, Visionobi, Kristy Harper, Joe Raygun, Itoa, Paul Roca, Sekev, Egres, Ghostchant, Boyson, Hampton, Jess Farley, G-Ha, Pixel82, Night Swimmers, Forbes, Charline, Scar Duggy, Mold Me With Joy, Eric Small, Christer Anderson, Carina Helen, Exswitch, Seamus, Bulu, Ikarus, Rodri Pan, Frnch, DB, Bigman Japan, Crawford, Dephex, 1Thirty, Denzel, Sticky Bandit, Kinno, Tenbagg, My Mate From College, Mr Miyagi, SLB Solden, Austria June 9-July 10 DJ Snare, Ambiont, DLR, Doc Scott, Bailey, Doree, Shifty, Dorian, Skore, March 27-April 2 Web www.electric-mountain-festival.com Jazz Fest Vienna Dossa & Locuzzed, Eksman, Emperor, Artists Nervo, Quintino, Michael Feiner, Full Metal Mountain EMX, Elize, Ernestor, Wastenoize, Etherwood, Askery, Rudy & Shany, AfroJack, Bassjackers, Vienna, Austria Hemagor, Austria F4TR4XX, Rapture,Fava, Fred V & Grafix, Ostblockschlampen, Rafitez Web www.jazzfest.wien Frederic Robinson, -

Now Here Live Internet Bidding with Special Auction

NOW HERE LIVE INTERNET BIDDING WITH SPECIAL AUCTION SERVICES We are delighted to announce that you are now able to bid online directly with SAS We have now launched the new SAS Live bidding platform Visit: auctions.specialauctionservices.com for more details Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Forrester (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) Music & Entertainment Auction Tuesday 17th September 2019 at 10.00 Viewing: For enquiries relating to the auction please contact: Monday 16th September 2019 10:00 - 16:00 09:00 morning of auction Otherwise by Appointment Saleroom One 81 Greenham Business Park NEWBURY RG19 6HW Christopher David Martin David Howe Proudfoot Music & Music & Telephone: 01635 580595 Mechanical Entertainment Entertainment Fax: 0871 714 6905 Music Email: [email protected] www.specialauctionservices.com Buyers Premium: 17.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 21% of the Hammer Price SAS Live Premium: 20% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24% of the Hammer Price Internet Buyers Premium: 22.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 27% of the Hammer Price As per our Terms and Conditions and with particular reference to autograph material or works, it is imperative that potential buyers or their agents have inspected pieces that interest them to ensure satisfaction with the lot prior to auction; the purchase will be made at their own risk. Special Auction Services will give indications of the provenance where stated by vendors. Subject to our normal Terms and Conditions, we cannot accept returns. ORDER OF AUCTION GRAMOPHONES & PHONOGRAPHS 1-143 VINYL RECORDS 144-448 CDs / CD BOX SETS 449-494 PSYCHEDELIC POSTERS 495-562 OTHER MUSIC POSTERS 563-577 MUSIC MEMORABILIA 578-627 FILM POSTERS 628-653 FILM & TV MEMORABILIA 654-661 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS 662-690 HI-FI 691-703 LOT 126 www.specialauctionservices.com 3 Gramophones & Phonographs 11.