Detroit Rock & Roll by Ben Edmonds for Our Purposes, The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stranglers - Peaches (The Very Best Of)

The Stranglers - Peaches (The Very Best Of) 24-09-2020 15:00 CEST The Stranglers - Peaches (The Very Best Of) blir tilgjengelig på vinyl For første gang på vinyl skal The Stranglers «Peaches (The Very Best Of)» gjøres tilgjengelig som dobbelt-LP-sett. Dette vil være den eneste «Best Of»- samlingen av The Stranglers som vil være tilgjengelig på vinyl. Stranglers «Peaches (The Very Best Of)» er tilgjengelig for forhåndsbestilling nå. The Stranglers ble dannet tidlig i 1974, og ble oppdaget via punkrock-scenen. Bandet etablerte sitt omdømme og store fanskare gjennom deres aggressive og kompromissløse stil. Bandets sound utviklet seg derimot gjennom hele karrieren, og ble aldri kategorisert til en spesifikk sjanger. Som et resultat av dette, er deres verk svært variert og enormt verdsatt. Hittil har bandet oppnådd 23 britiske Top 40 singler og 17 britiske Top 40 album. The Stranglers er et av de lengst overlevende og mest kjente bandene som har sitt utspring fra den britiske punk-scenen. «Peaches (The Very Best Of)» er en samling av deres mest berømte låter fra de første to tiårene av deres berømte karriere, inkludert ikoniske spor som «Peaches», «Golden Brown», «No More Heroes» og «Hanging Around». Side A 1. Peaches 2. Golden Brown 3. Walk On By 4. No More Heroes 5. Skin Deep Side B 1. Hanging Around 2. All Day And All Of The Night 3. Straighten Out 4. Nice ‘N’ Sleazy 5. Strange Little Girl 6. Who Wants The World Side C 1. Something Better Change 2. Always The Sun (Sunny Side Up Mix) 3. European Female 4. -

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Song Artist 25 Or 6 to 4 Chicago 5 Years Time Noah and the Whale A

A B 1 Song Artist 2 25 or 6 to 4 Chicago 3 5 Years Time Noah and the Whale 4 A Horse with No Name America 5 Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus 6 Adelaide Old 97's 7 Adelaide 8 Africa Bamba Santana 9 Against the Wind Bob Seeger 10 Ain't to Proud to Beg The Temptations 11 All Along the W…. Dylan/ Hendrix 12 Back in Black ACDC 13 Bad Leroy Brown Jim Croce 14 Bad Moon Risin' CCR 15 Bad to the Bone George Thorogood 16 Bamboleo Gipsy Kings 17 Black Horse and… KT Tunstall 18 Born to be Wild Steelers Wheels 19 Brain Stew Green Day 20 Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison 21 Chasing Cars Snow Patrol 22 Cheesburger in Para… Jimmy Buffett 23 Clocks Coldplay 24 Close to You JLS 25 Close to You 26 Come as you Are Nirvana 27 Dead Flowers Rolling Stones 28 Down on the Corner CCR 29 Drift Away Dobie Gray 30 Duende Gipsy Kings 31 Dust in the Wind Kansas 32 El Condor Pasa Simon and Garfunkle 33 Every Breath You Take Sting 34 Evil Ways Santana 35 Fire Bruce Springsteen Pointer Sis.. 36 Fire and Rain James Taylor A B 37 Firework Katy Perry 38 For What it's Worth Buffalo Springfield 39 Forgiveness Collective Soul 40 Free Bird Lynyrd Skynyrd 41 Free Fallin Tom Petty 42 Give me One Reason Tracy Chapman 43 Gloria Van Morrison 44 Good Riddance Green Day 45 Have You Ever Seen… CCR 46 Heaven Los Lonely Boys 47 Hey Joe Hendrix 48 Hey Ya! Outcast 49 Honkytonk Woman Rolling Stones 50 Hotel California Eagles 51 Hotel California 52 Hotel California Eagles 53 Hotel California 54 I Won't Back Down Tom Petty 55 I'll Be Missing You Puff Daddy 56 Iko Iko Dr. -

STICK MEN - Tony Levin and Pat Mastelo�O, the Powerhouse Bass and Drums of the Group King Crimson for a Few Decades, Bring That Tradi�On to All Their Playing

STICK MEN - Tony Levin and Pat Masteloo, the powerhouse bass and drums of the group King Crimson for a few decades, bring that tradion to all their playing. Levin plays the Chapman Sck, from which the band takes it’s name. Having bass and guitar strings, the Chapman Sck funcons at mes like two instruments. Markus Reuter plays his selfdesigned touch style guitar – again covering much more ground than a guitar or a bass. And Masteloo’s drumming encompasses not just the acousc kit, but a unique electronic setup too, allowing him to add loops, samples, percussion and more. TONY LEVIN - Born in Boston, Tony Levin started out in classical music, playing bass in the Rochester Philharmonic. Then moving into jazz and rock, he has had a notable career, recording and touring with John Lennon, Pink Floyd, Yes, Alice Cooper, Gary Burton, Buddy Rich and many more. He has also released 5 solo CDs and three books. In addion to touring with Sck Men, since more than 30 years is currently a member of King Crimson and Peter Gabriel Band, and jazz bands Levin Brothers and L’Image. His popular website, tonylevin.com, featured one of the web’s first blogs, and has over 4 million visits. PAT MASTELOTTO - Very rarely does a drummer go on to forge the most successful career on the demise of their former hit band. Phil Collins and Dave Grohl have managed it, so too has Pat Masteloo, a self taught drummer from Northern California, who has also been involved with pushing the envelope of electronic drumming. -

Course Outline and Syllabus the Fab Four and the Stones: How America Surrendered to the Advance Guard of the British Invasion

Course Outline and Syllabus The Fab Four and the Stones: How America surrendered to the advance guard of the British Invasion. This six-week course takes a closer look at the music that inspired these bands, their roots-based influences, and their output of inspired work that was created in the 1960’s. Topics include: The early days, 1960-62: London, Liverpool and Hamburg: Importing rhythm and blues and rockabilly from the States…real rock and roll bands—what a concept! Watch out, world! The heady days of 1963: Don’t look now, but these guys just might be more than great cover bands…and they are becoming very popular…Beatlemania takes off. We can write songs; 1964: the rock and roll band as a creative force. John and Paul, their yin and yang-like personal and musical differences fueling their creative tension, discover that two heads are better than one. The Stones, meanwhile, keep cranking out covers, and plot their conquest of America, one riff at a time. The middle periods, 1965-66: For the boys from Liverpool, waves of brilliant albums that will last forever—every cut a memorable, sing-along winner. While for the Londoners, an artistic breakthrough with their first all--original record. Mick and Keith’s tempestuous relationship pushes away band founder Brian Jones; the Stones are established as a force in the music world. Prisoners of their own success, 1967-68: How their popularity drove them to great heights—and lowered them to awful depths. It’s a long way from three chords and a cloud of dust. -

Jess Glynne's

CHART WEEK 16 CLUB CHARTS UPFRONT CLUB TOP 30 URBAN TOP 20 COOL CUTS TOP 20 TW LW WKS ARTIST/TITLE/LABEL TW LW WKS ARTIST/TITLE/LABEL TW ARTIST/TITLE 1 9 5 Lucas & Steve Say Something / Atlantic/Spinnin' 1 Mike Mago Wake Up 2 3 4 Friend Within Waiting / Toolroom 2 Becky Hill & Weiss 3 18 5 Tom Budin Undercontrol / Onelove I Could Get Used To This , online and retail stores distributors. 4 12 3 Mybadd + Sam Gray Sugar / Humble Angel 3 Jax Jones & Martin Solveig Present 5 1 4 Ferreck Dawn, Robosonic & Nikki Ambers In My Arms / Defected Europa Ft Maddison Beer 6 27 4 Lee Dagger & Courtney Harrell So Lost Hearted / Tazmania All Day & Night 7 25 3 Purple Disco Machine Body Funk / Positiva 4 Hot Chip Hungry Child 8 13 3 Majestic I Wanna Be Down / 3 Beat 5 Peggy Gou Starry Night 9 RE 2 Rika Wanna Know / Virgin 6 Kove Ft Ben Duffy Echoes 10 20 3 Snakehips Ft Rivers Cuomo & Kyle Gucci Rock N Rolla / Hoffman West & J BALVIN SEAN PAUL 7 Leftwing : Kody I Feel It 11 30 2 Ina Wroldsen X Dynoro Obsessed / Ministry Of Sound 1 5 3 Sean Paul & J Balvin Contra La Pared / Island 8 The Chemical Brothers 12 22 2 Jay Pryor So What / Positiva/Selected 2 1 4 Mariah Carey A No No / Epic No Geography 13 11 4 Sean Finn & Corona The Rhythm Of The Night / Nitron 3 8 4 T Mulla Link Up / Virgin 9 Chase & Status Ft Irah Program 14 31 2 Jax Jones & Martin Solveig Ft Madison Beer All Day And Night / Polydor 4 4 5 Col3trane x DJDS x Raye The Fruits / Island 10 Tom Hall Lifeline 15 19 3 Jack Back Survivor/Put Your Phone Down (Low) / DFTD 5 10 2 Tory Lanez Freaky / Mad Love/Interscope 11 Kokiri Ft Joe Killington Friends 16 14 3 Keelie Walker This Is What It's Like / 2220 6 7 3 Jay Sean Ft Gucci Mane & Asian Doll With You / Republic 12 Lee Foss, Eli Brown & Anabel 17 15 2 RTEN Volume 1 (EP): Cheeky One (Freak)/I Think.. -

Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century Saesha Senger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.011 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Senger, Saesha, "Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 150. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/150 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

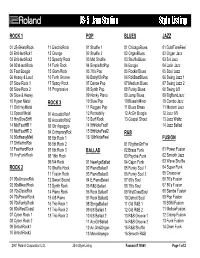

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing ROCK 1 POP BLUES JAZZ 01 JS-5HardRock 11 ElectricRock 01 Shuffle 1 01 ChicagoBlues 01 DublTimeFeel 02 BritHardRck1 12 Grunge 02 Shuffle 2 02 OrganBlues 02 Organ Jazz 03 BritHardRck2 13 Speedy Rock 03 Mid Shuffle 03 ShuffleBlues 03 5/4 Jazz 04 80'sHardRock 14 Funk Rock 04 Simple8btPop 04 Boogie 04 Latin Jazz 05 Fast Boogie 15 Glam Rock 05 70's Pop 05 Rockin'Blues 05 Soul Jazz 06 Heavy & Loud 16 Funk Groove 06 Early80'sPop 06 RckBeatBlues 06 Swing Jazz 1 07 Slow Rock 1 17 Spacy Rock 07 Dance Pop 07 Medium Blues 07 Swing Jazz 2 08 Slow Rock 2 18 Progressive 08 Synth Pop 08 Funky Blues 08 Swing 6/8 09 Slow & Heavy 09 Honky Piano 09 Jump Blues 09 BigBandJazz 10 Hyper Metal ROCK 3 10 Slow Pop 10 BluesInMinor 10 Combo Jazz 11 Old HvyMetal 11 Reggae Pop 11 Blues Brass 11 Modern Jazz 12 Speed Metal 01 AcousticRck1 12 Rockabilly 12 AcGtr Boogie 12 Jazz 6/8 13 HvySlowShffl 02 AcousticRck2 13 Surf Rock 13 Gospel Shout 13 Jazz Waltz 14 MidFastHR 1 03 Gtr Arpeggio 14 8thNoteFeel1 14 Jazz Ballad 15 MidFastHR 2 04 CntmpraryRck 15 8thNoteFeel2 R&B 16 80sHeavyMetl 05 8bt Rock 1 16 16thNoteFeel FUSION 17 ShffleHrdRck 06 8bt Rock 2 01 RhythmGtrFnk 18 FastHardRock 07 8bt Rock 3 BALLAD 02 Brass Funk 01 Power Fusion 19 HvyFunkRock 08 16bt Rock 03 Psyche-Funk 02 Smooth Jazz 09 5/4 Rock 01 NewAgeBallad 04 Cajun Funk 03 Wave Shuffle ROCK 2 10 Shuffle Rock 02 PianoBallad1 05 Funky Soul 1 04 Super Funk 11 Fusion Rock 03 PianoBallad2 06 Funky Soul 2 05 Crossover 01 90sGrooveRck 12 Sweet Sound 04 E.PianoBalad 07 60's Soul 06 -

JD Reynolds Is an Artist in the Truest Sense of the Word

JD Reynolds is an artist in the truest sense of the word. A true singer, a real songwriter, a neoteric producer, an incredible dancer and striking performer, all wrapped up in a stunning package that could grace the cover of any magazine in the world, and yet, her down to earth country girl charm is what makes this extraordinary artist so real. JD Reynolds was born an artist. “It’s in my blood. Music, melody, lyrics and dance flow through my veins, gifts straight from God for which I am thankful”. JD’s Mother had Elvis, Michael Jackson, Prince, Roy Orbison, Dolly Parton and Whitney Houston on daily replay in the house, so JD grew up listening to the King of Rock ‘n Roll, The Prince of Pop, The PRINCE of Everything, The Caruso of Rock, The Queen of Country Music and The Queen of the Night. JD’s sound is fresh originality for country music. “My entire album came to me like a bolt of lightning, the JD sound, my sound, respecting country music routes yet having my own next level twist”. As an up and coming producer, JD teamed up with seasoned producer Braddon Williams to co-produce what country music insiders have nicknamed “The Jagged Little Pill of country". Braddon has achieved more than thirty top-ten hits, amassed over thirty times platinum in record sales, and his work has received both Grammy and ARIA award nominations, credits include Beyoncé, Snoop Dogg, P Diddy, The Script, Kelly Clarkson, and his latest favourite, JD Reynolds. Braddon knew he was helping to create a unique country album for an incredible talent. -

HITMAKERS – 6 X 60M Drama

HITMAKERS – 6 x 60m drama LOGLINE In Sixties London, the managers of the Beatles, the Stones and the Who struggle to marry art and commerce in a bid to become the world’s biggest hitmakers. CHARACTERS Andrew Oldham (19), Beatles publicist and then manager of the Rolling Stones. A flash, mouthy trouble-maker desperate to emulate Brian Epstein’s success. His bid to create the anti-Beatles turns him from Epstein wannabe to out-of-control anarchist, corrupted by the Stones lifestyle and alienated from his girlfriend Sheila. For him, everything is a hustle – work, relationships, his own psyche – but always underpinned by a desire to surprise and entertain. Suffers from (initially undiagnosed) bi-polar disorder, which is exacerbated by increasing drug use, with every high followed by a self-destructive low. Nobody in the Sixties burns brighter: his is the legend that’s never been told on screen, the story at the heart of Hitmakers. Brian Epstein (28), the manager of the Beatles. A man striving to create with the Beatles the success he never achieved in entertainment himself (as either actor or fashion designer). Driven by a naive, egotistical sense of destiny, in the process he basically invents what we think of as the modern pop manager. He’s an emperor by the age of 30 – but this empire is constantly at risk of being undone by his desperate (and – to him – shameful) homosexual desires for inappropriate men, and the machinations of enemies jealous of his unprecedented, upstart success. At first he sees Andrew as a protege and confidant, but progressively as a threat. -

Fēnix® 6 Series Owner's Manual

FĒNIX® 6 SERIES Owner’s Manual © 2019 Garmin Ltd. or its subsidiaries All rights reserved. Under the copyright laws, this manual may not be copied, in whole or in part, without the written consent of Garmin. Garmin reserves the right to change or improve its products and to make changes in the content of this manual without obligation to notify any person or organization of such changes or improvements. Go to www.garmin.com for current updates and supplemental information concerning the use of this product. Garmin®, the Garmin logo, ANT+®, Approach®, Auto Lap®, Auto Pause®, Edge®, fēnix®, inReach®, QuickFit®, TracBack®, VIRB®, Virtual Partner®, and Xero® are trademarks of Garmin Ltd. or its subsidiaries, registered in the USA and other countries. Body Battery™, Connect IQ™, Garmin Connect™, Garmin Explore™, Garmin Express™, Garmin Golf™, Garmin Move IQ™, Garmin Pay™, HRM-Run™, HRM-Tri™, tempe™, TruSwing™, TrueUp™, Varia™, Varia Vision™, and Vector™ are trademarks of Garmin Ltd. or its subsidiaries. These trademarks may not be used without the express permission of Garmin. Android™ is a trademark of Google Inc. Apple®, iPhone®, iTunes®, and Mac® are trademarks of Apple Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries. The BLUETOOTH® word mark and logos are owned by the Bluetooth SIG, Inc. and any use of such marks by Garmin is under license. The Cooper Institute®, as well as any related trademarks, are the property of The Cooper Institute. Di2™ is a trademark of Shimano, Inc. Shimano® is a registered trademark of Shimano, Inc. The Spotify® software is subject to third-party licenses found here: https://developer.spotify.com/legal/third- party-licenses. -

Bob Dylan Performs “It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009

Volume 19, Number 4, December 2013 Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory A Foreign Sound to Your Ear: Bob Dylan Performs “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009 * Steven Rings NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.13.19.4/mto.13.19.4.rings.php KEYWORDS: Bob Dylan, performance, analysis, genre, improvisation, voice, schema, code ABSTRACT: This article presents a “longitudinal” study of Bob Dylan’s performances of the song “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” over a 45-year period, from 1964 until 2009. The song makes for a vivid case study in Dylanesque reinvention: over nearly 800 performances, Dylan has played it solo and with a band (acoustic and electric); in five different keys; in diverse meters and tempos; and in arrangements that index a dizzying array of genres (folk, blues, country, rockabilly, soul, arena rock, etc.). This is to say nothing of the countless performative inflections in each evening’s rendering, especially in Dylan’s singing, which varies widely as regards phrasing, rhythm, pitch, articulation, and timbre. How can music theorists engage analytically with such a moving target, and what insights into Dylan’s music and its meanings might such a study reveal? The present article proposes one set of answers to these questions. First, by deploying a range of analytical techniques—from spectrographic analysis to schema theory—it demonstrates that the analytical challenges raised by Dylan’s performances are not as insurmountable as they might at first appear, especially when approached with a strategic and flexible methodological pluralism.