Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elite Music Productions This Music Guide Represents the Most Requested Songs at Weddings and Parties

Elite Music Productions This Music Guide represents the most requested songs at Weddings and Parties. Please circle songs you like and cross out the ones you don’t. You can also write-in additional requests on the back page! WEDDING SONGS ALL TIME PARTY FAVORITES CEREMONY MUSIC CELEBRATION THE TWIST HERE COMES THE BRIDE WE’RE HAVIN’ A PARTY SHOUT GOOD FEELIN’ HOLIDAY THE WEDDING MARCH IN THE MOOD YMCA FATHER OF THE BRIDE OLD TIME ROCK N ROLL BACK IN TIME INTRODUCTION MUSIC IT TAKES TWO STAYIN ALIVE ST. ELMOS FIRE, A NIGHT TO REMEMBER, RUNAROUND SUE MEN IN BLACK WHAT I LIKE ABOUT YOU RAPPERS DELIGHT GET READY FOR THIS, HERE COMES THE BRIDE BROWN EYED GIRL MAMBO #5 (DISCO VERSION), ROCKY THEME, LOVE & GETTIN’ JIGGY WITH IT LIVIN, LA VIDA LOCA MARRIAGE, JEFFERSONS THEME, BANG BANG EVERYBODY DANCE NOW WE LIKE TO PARTY OH WHAT A NIGHT HOT IN HERE BRIDE WITH FATHER DADDY’S LITTLE GIRL, I LOVED HER FIRST, DADDY’S HANDS, FATHER’S EYES, BUTTERFLY GROUP DANCES KISSES, HAVE I TOLD YOU LATELY, HERO, I’LL ALWAYS LOVE YOU, IF I COULD WRITE A SONG, CHICKEN DANCE ALLEY CAT CONGA LINE ELECTRIC SLIDE MORE, ONE IN A MILLION, THROUGH THE HANDS UP HOKEY POKEY YEARS, TIME IN A BOTTLE, UNFORGETTABLE, NEW YORK NEW YORK WALTZ WIND BENEATH MY WINGS, YOU LIGHT UP MY TANGO YMCA LIFE, YOU’RE THE INSPIRATION LINDY MAMBO #5BAD GROOM WITH MOTHER CUPID SHUFFLE STROLL YOU RAISE ME UP, TIMES OF MY LIFE, SPECIAL DOLLAR WINE DANCE MACERENA ANGEL, HOLDING BACK THE YEARS, YOU AND CHA CHA SLIDE COTTON EYED JOE ME AGAINST THE WORLD, CLOSE TO YOU, MR. -

Hothouse Flowers

MTM Checks Out Europe's Own MTV Unplugged. Also, GrooveMix Looks At French Club Charts. See page 10 & 12. Europe's Music Radio Newsweekly Volume 10 . Issue 11 . March 13, 1993 . £ 3, US$ 5, ECU 4 Radio Wins UK PolyGram Operating Copyright Battle Income Up 7% broadcasting revenue, including by Thom Duffy & income from sponsorship, barter Mike McGeever and contra deals for the first time, by Steve Wonsiewicz Record companies inthe UK as well as advertising revenue. Worldwide music and entertain- have been dealt a major setback The ratefor stations with net ment group PolyGram reported in their bid to boost the royalty broadcastingrevenuebetween a 7.3% increaseinoperating payments they receive from com- US$1.02 million and US$525.000 income to Dfl 789 million (app. mercial radio stations, under a will drop to 3% and 2% for those US$448 million) on a 4.6% rise ruling handed down March 2 by with net income below in sales to Dfl 6.62 billion last the Copyright Tribunal. US$525.000. The royaltiesare year, despite a severe recession DANISH GRAMMIES - Danish band Gangway (BMG/Genlyd Den- In an action brought by the retroactive to April 1, 1991. in several of its key European mark) received four prizes in this year's Danish Grammy Show while Association ofIndependent The total operating profit of markets. Lisa Nilsson (Diesel Music, Sweden) took two awards. Pictured (4) are: Radio Contractors (AIRC) to set the commercial UK radio indus- Net income for thefiscal Tonja Pedersen (musician, Lisa Nilsson), Lasse Illinton (Gangway), BMG new broadcast royalty rates for 79 try in 1990-91 was approximately year ended December 31 was up label manager Susanne Kier, Diesel Music MD Torbjorn Sten, Lisa Nils- commercialradiocompanies, US$11 millionwithCapital 13.5% to Dfl 506 million. -

Download This List As PDF Here

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of 5.1 SACD, DVD-Audio and Blu-Ray Surround Discs JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow Dishwalla Services, State Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD Anderson, Jim Donna Byrne Licensed to Thrill SACD Anderson, Jim Jane Ira Bloom Sixteen Sunsets BD-A 2018 Grammy Winner: Anderson, Jim 2018 Jane Ira Bloom Early Americans BD-A Best Surround Album Wild Lines: Improvising on Emily Anderson, Jim 2020 Jane Ira Bloom DSD/DXD Download Dickinson Jazz Ambassadors/Sammy Anderson, Jim The Sammy Sessions BD-A Nestico Masur/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Kverndokk: Symphonic Dances BD-A Orchestra Anderson, Jim Patricia Barber Modern Cool BD-A SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2020 Patricia Barber Higher with Ulrike Schwarz Download SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2021 Patricia Barber Clique Download Svilvay/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Mortensen: Symphony Op. -

Bob Dylan Performs “It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009

Volume 19, Number 4, December 2013 Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory A Foreign Sound to Your Ear: Bob Dylan Performs “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009 * Steven Rings NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.13.19.4/mto.13.19.4.rings.php KEYWORDS: Bob Dylan, performance, analysis, genre, improvisation, voice, schema, code ABSTRACT: This article presents a “longitudinal” study of Bob Dylan’s performances of the song “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” over a 45-year period, from 1964 until 2009. The song makes for a vivid case study in Dylanesque reinvention: over nearly 800 performances, Dylan has played it solo and with a band (acoustic and electric); in five different keys; in diverse meters and tempos; and in arrangements that index a dizzying array of genres (folk, blues, country, rockabilly, soul, arena rock, etc.). This is to say nothing of the countless performative inflections in each evening’s rendering, especially in Dylan’s singing, which varies widely as regards phrasing, rhythm, pitch, articulation, and timbre. How can music theorists engage analytically with such a moving target, and what insights into Dylan’s music and its meanings might such a study reveal? The present article proposes one set of answers to these questions. First, by deploying a range of analytical techniques—from spectrographic analysis to schema theory—it demonstrates that the analytical challenges raised by Dylan’s performances are not as insurmountable as they might at first appear, especially when approached with a strategic and flexible methodological pluralism. -

Soundtrack and Garnering Accolades for Their Debut Album “Remind Me in Three Days.” Check out Our Exclusive Interview on Page 7

Ver su s Entertainment & Culture at Vanderbilt DECEMBER 3—DECEMBER 9, 2008 VOL. 46, NO. 26 “Abstract Progressive” rapping duo The Knux are giving Vincent Chase his soundtrack and garnering accolades for their debut album “Remind Me in Three Days.” Check out our exclusive interview on page 7. We saw a lot of movies over break. We weigh in on which to see and … from which to fl ee. “808s and Heartbreaks” is really good. Hey, Kanye, hey. PLACES TO GO, PEOPLE TO SEE THURSDAY, DECEMBER 4 FRIDAY, DECEMBER 5 SATURDAY, DECEMBER 6 The Regulars Harley Allen Band — Station Inn Parachute Musical and KinderCastle with Noises Carols & Cocoa — Barnes and Noble, Cool THE RUTLEDGE The go-to joint for bluegrass in the Music City features Harley Allen, 10 — The Mercy Lounge and Cannery Ballroom Springs 410 Fourth Ave. S. 37201 Part of the Mercy Lounge’s Winter of Dreamz musical showcase, a well-known song writer who’s worked with Garth Brooks, Dierks Need to get into the Christmas spirit? The Battle Ground Academy 782-6858 Bentley and Gary Allan to name a few. Make sure to see this living Friday’s event showcases Parachute Musical and KinderCastle along Middle School Chorus will lead you in some of your favorite seasonal legend in action. ($10, 9 p.m.) with opener Noises 10. Head to the Mercy Lounge to enjoy some carols as you enjoy delicious hot chocolate. (Free, 11 a.m., 1701 MERCY LOUNGE/CANNERY live local music and $2.50 pints courtesy of Winter of Dreamz co- Mallory Lane, Brentwood) presenter Sweetwater 420. -

Art to Commerce: the Trajectory of Popular Music Criticism

Art to Commerce: The Trajectory of Popular Music Criticism Thomas Conner and Steve Jones University of Illinois at Chicago [email protected] / [email protected] Abstract This article reports the results of a content and textual analysis of popular music criticism from the 1960s to the 2000s to discern the extent to which criticism has shifted focus from matters of music to matters of business. In part, we believe such a shift to be due likely to increased awareness among journalists and fans of the industrial nature of popular music production, distribution and consumption, and to the disruption of the music industry that began in the late 1990s with the widespread use of the Internet for file sharing. Searching and sorting the Rock’s Backpages database of over 22,000 pieces of music journalism for keywords associated with the business, economics and commercial aspects of popular music, we found several periods during which popular music criticism’s focus on business-related concerns seemed to have increased. The article discusses possible reasons for the increases as well as methods for analyzing a large corpus of popular music criticism texts. Keywords: music journalism, popular music criticism, rock criticism, Rock’s Backpages Though scant scholarship directly addresses this subject, music journalists and bloggers have identified a trend in recent years toward commerce-specific framing when writing about artists, recording and performance. Most music journalists, according to Willoughby (2011), “are writing quasi shareholder reports that chart the movements of artists’ commercial careers” instead of artistic criticism. While there may be many reasons for such a trend, such as the Internet’s rise to prominence not only as a medium for distribution of music but also as a medium for distribution of information about music, might it be possible to discern such a trend? Our goal with the research reported here was an attempt to empirically determine whether such a trend exists and, if so, the extent to which it does. -

Final Version

This research has been supported as part of the Popular Music Heritage, Cultural Memory and Cultural Identity (POPID) project by the HERA Joint Research Program (www.heranet.info) which is co-funded by AHRC, AKA, DASTI, ETF, FNR, FWF, HAZU, IRCHSS, MHEST, NWO, RANNIS, RCN, VR and The European Community FP7 2007–2013, under ‘the Socio-economic Sciences and Humanities program’. ISBN: 978-90-76665-26-9 Publisher: ERMeCC, Erasmus Research Center for Media, Communication and Culture Printing: Ipskamp Drukkers Cover design: Martijn Koster © 2014 Arno van der Hoeven Popular Music Memories Places and Practices of Popular Music Heritage, Memory and Cultural Identity *** Popmuziekherinneringen Plaatsen en praktijken van popmuziekerfgoed, cultureel geheugen en identiteit Thesis to obtain the degree of Doctor from the Erasmus University Rotterdam by command of the rector magnificus Prof.dr. H.A.P Pols and in accordance with the decision of the Doctorate Board The public defense shall be held on Thursday 27 November 2014 at 15.30 hours by Arno Johan Christiaan van der Hoeven born in Ede Doctoral Committee: Promotor: Prof.dr. M.S.S.E. Janssen Other members: Prof.dr. J.F.T.M. van Dijck Prof.dr. S.L. Reijnders Dr. H.J.C.J. Hitters Contents Acknowledgements 1 1. Introduction 3 2. Studying popular music memories 7 2.1 Popular music and identity 7 2.2 Popular music, cultural memory and cultural heritage 11 2.3 The places of popular music and heritage 18 2.4 Research questions, methodological considerations and structure of the dissertation 20 3. The popular music heritage of the Dutch pirates 27 3.1 Introduction 27 3.2 The emergence of pirate radio in the Netherlands 28 3.3 Theory: the narrative constitution of musicalized identities 29 3.4 Background to the study 30 3.5 The dominant narrative of the pirates: playing disregarded genres 31 3.6 Place and identity 35 3.7 The personal and cultural meanings of illegal radio 37 3.8 Memory practices: sharing stories 39 3.9 Conclusions and discussion 42 4. -

L the Charlatans UK the Charlatans UK Vs. the Chemical Brothers

These titles will be released on the dates stated below at physical record stores in the US. The RSD website does NOT sell them. Key: E = Exclusive Release L = Limited Run / Regional Focus Release F = RSD First Release THESE RELEASES WILL BE AVAILABLE AUGUST 29TH ARTIST TITLE LABEL FORMAT QTY Sounds Like A Melody (Grant & Kelly E Alphaville Rhino Atlantic 12" Vinyl 3500 Remix by Blank & Jones x Gold & Lloyd) F America Heritage II: Demos Omnivore RecordingsLP 1700 E And Also The Trees And Also The Trees Terror Vision Records2 x LP 2000 E Archers of Loaf "Raleigh Days"/"Street Fighting Man" Merge Records 7" Vinyl 1200 L August Burns Red Bones Fearless 7" Vinyl 1000 F Buju Banton Trust & Steppa Roc Nation 10" Vinyl 2500 E Bastille All This Bad Blood Capitol 2 x LP 1500 E Black Keys Let's Rock (45 RPM Edition) Nonesuch 2 x LP 5000 They's A Person Of The World (featuring L Black Lips Fire Records 7" Vinyl 750 Kesha) F Black Crowes Lions eOne Music 2 x LP 3000 F Tommy Bolin Tommy Bolin Lives! Friday Music EP 1000 F Bone Thugs-N-Harmony Creepin' On Ah Come Up Ruthless RecordsLP 3000 E David Bowie ChangesNowBowie Parlophone LP E David Bowie ChangesNowBowie Parlophone CD E David Bowie I’m Only Dancing (The Soul Tour 74) Parlophone 2 x LP E David Bowie I’m Only Dancing (The Soul Tour 74) Parlophone CD E Marion Brown Porto Novo ORG Music LP 1500 F Nicole Bus Live in NYC Roc Nation LP 2500 E Canned Heat/John Lee Hooker Hooker 'N Heat Culture Factory2 x LP 2000 F Ron Carter Foursight: Stockholm IN+OUT Records2 x LP 650 F Ted Cassidy The Lurch Jackpot Records7" Vinyl 1000 The Charlatans UK vs. -

Is Rock Music in Decline? a Business Perspective

Jose Dailos Cabrera Laasanen Is Rock Music in Decline? A Business Perspective Helsinki Metropolia University of Applied Sciences Bachelor of Business Administration International Business and Logistics 1405484 22nd March 2018 Abstract Author(s) Jose Dailos Cabrera Laasanen Title Is Rock Music in Decline? A Business Perspective Number of Pages 45 Date 22.03.2018 Degree Bachelor of Business Administration Degree Programme International Business and Logistics Instructor(s) Michael Keaney, Senior Lecturer Rock music has great importance in the recent history of human kind, and it is interesting to understand the reasons of its de- cline, if it actually exists. Its legacy will never disappear, and it will always be a great influence for new artists but is important to find out the reasons why it has become what it is in now, and what is the expected future for the genre. This project is going to be focused on the analysis of some im- portant business aspects related with rock music and its de- cline, if exists. The collapse of Gibson guitars will be analyzed, because if rock music is in decline, then the collapse of Gibson is a good evidence of this. Also, the performance of independ- ent and major record labels through history will be analyzed to understand better the health state of the genre. The same with music festivals that today seem to be increasing their popularity at the expense of smaller types of live-music events. Keywords Rock, music, legacy, influence, artists, reasons, expected, fu- ture, genre, analysis, business, collapse, -

Filter Take My Picture Lyrics

Filter take my picture lyrics Continue 1999 single Filter Take a PictureSingle by Filter from title of RecordRejanuary 18, 2000 (2000-01-18) author (s) Richard PatrickProducer (s) Ben Gross Patrick Geno Lenardo Rae DiLeo Filter Singles Chronology Welcome to the Crease (1999) Take the picture (2000) Best Things (2000) Music Video Take a picture on YouTube Take a picture of the song American rock band Filter, released in 1999 as the second single from the second studio album, The name of the record. The song became a hit in early 2000 after its release on January 18, peaking at number 12 on the Billboard Hot 100 and at number 3 in Canada. It also became a top ten hit in New York, peaking at number eight on the SINGLE charts. Background and lyrics filter frontman and founding member Richard Patrick said the song was about him getting drunk on a plane and swiping all his clothes. Patrick expanded in more detail in a 2008 retrospective interview: When I wrote the chorus on Take a Picture it was right after my friend was like, do you remember anything you did last night? And I said, What are you talking about? She said, Oh my God, you threw beer bottles out of a taxi window at a police officer's car. Do you remember that? And I said, oh my God, could you take a picture of me because I won't remember. And that line just kind of stuck. Weeks later, I had another drunken experience - being on a plane and being blacked out and not feeling well and taking my shirt half in and out of consciousness - and I'm in the back of a paddy wagon. -

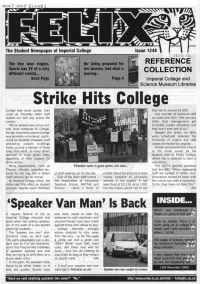

Felix Issue 1223, 2002

IMP £ { XAft } The Student Newspaper of Imperial College Issue 1248 I S/ U /2__ The five wise virgins. Bo' being prepared for REFERENCE Sports has XV of a very her journey. And what a different variety... journey... B§ COLLECTION Back Page Page 4 Imperial College and Science Museum Libraries Strike Hits College College was much quieter than that rise to around £4,000. usual on Thursday when staff One member of technical staff walked out over pay across the on strike told Felix, "We are very capital. bitter that management get Official pickets were set up out- £16,000 London allowance and side most entrances to College, they won't even talk to us." though movement around College Despite the strike, no talks was generally unhindered, partic- were scheduled between the ularly for students. However, staff University of London and staff protesting outside buildings unions to resolve the dispute. made up only a fraction of those Unison announced that a focus away from work, as many others of the strike would be the declined to cross picket lines, Queen's visit to King's College, regardless of their support for where she is expected to open a strike action. new library. Many departments, such as Picketers were in good spirits, but cold.. The AUT's general secretary Physics, officially cancelled lec- told the BBC "When reasonable turers for the day, but in others of staff walking out for the day. protest about the amount of extra staff are pushed to strike, vice- most lectures ran as normal. Four of the main staff unions - money awarded to university chancellors should sit down with At Imperial College Union, the the Association of University workers in the capital. -

ARTIST INDEX(Continued)

ChartARTIST Codes: CJ (Contemporary Jazz) INDEXINT (Internet) RBC (R&B/Hip-Hop Catalog) –SINGLES– DC (Dance Club Songs) LR (Latin Rhythm) RP (Rap Airplay) –ALBUMS– CL (Traditional Classical) JZ (Traditional Jazz) RBL (R&B Albums) A40 (Adult Top 40) DES (Dance/Electronic Songs) MO (Alternative) RS (Rap Songs) B200 (The Billboard 200) CX (Classical Crossover) LA (Latin Albums) RE (Reggae) AC (Adult Contemporary) H100 (Hot 100) ODS (On-Demand Songs) STS (Streaming Songs) BG (Bluegrass) EA (Dance/Electronic) LPA (Latin Pop Albums) RLP (Rap Albums) ARB (Adult R&B) HA (Hot 100 Airplay) RB (R&B Songs) TSS (Tropical Songs) BL (Blues) GA (Gospel) LRS (Latin Rhythm Albums) RMA (Regional Mexican Albums) CA (Christian AC) HD (Hot Digital Songs) RBH (R&B Hip-Hop) XAS (Holiday Airplay) MAY CA (Country) HOL (Holiday) NA (New Age) TSA (Tropical Albums) CS (Country) HSS (Hot 100 Singles Sales) RKA (Rock Airplay) XMS (Holiday Songs) CC (Christian) HS (Heatseekers) PCA (Catalog) WM (World) CST (Christian Songs) LPS (Latin Pop Songs) RMS (Regional Mexican Songs) 15 CCA (Country Catalog) IND (Independent) RBA (R&B/Hip-Hop) DA (Dance/Mix Show Airplay) LT (Hot Latin Songs) RO (Hot Rock Songs) 2021 $NOT HS 23 BIG30 H100 80; RBH 34 NAT KING COLE JZ 5 -F- PETER HOLLENS CX 13 LAKE STREET DIVE RKA 43 21 SAVAGE B200 111; H100 54; HD 21; RBH 25; BIG DADDY WEAVE CA 20; CST 39 PHIL COLLINS HD 36 MARIANNE FAITHFULL NA 3 WHITNEY HOUSTON B200 190; RBL 17 KENDRICK LAMAR B200 51, 83; PCA 5, 17; RS 19; STM 35 RBA 26, 40; RLP 23 BIG SCARR B200 116 OLIVIA COLMAN CL 12 CHET