Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Webfile121848.Pdf

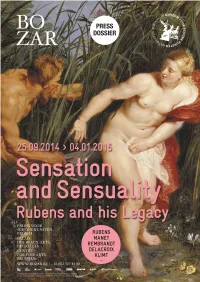

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

Honthorst, Gerrit Van Also Known As Honthorst, Gerard Van Gherardo Della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Honthorst, Gerrit van Also known as Honthorst, Gerard van Gherardo della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656 BIOGRAPHY Gerrit van Honthorst was born in Utrecht in 1592 to a large Catholic family. His father, Herman van Honthorst, was a tapestry designer and a founding member of the Utrecht Guild of St. Luke in 1611. After training with the Utrecht painter Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), Honthorst traveled to Rome, where he is first documented in 1616.[1] Honthorst’s trip to Rome had an indelible impact on his painting style. In particular, Honthorst looked to the radical stylistic and thematic innovations of Caravaggio (Roman, 1571 - 1610), adopting the Italian painter’s realism, dramatic chiaroscuro lighting, bold colors, and cropped compositions. Honthorst’s distinctive nocturnal settings and artificial lighting effects attracted commissions from prominent patrons such as Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1577–1633), Cosimo II, the Grand Duke of Tuscany (1590–1621), and the Marcheses Benedetto and Vincenzo Giustiniani (1554–1621 and 1564–1637). He lived for a time in the Palazzo Giustiniani in Rome, where he would have seen paintings by Caravaggio, and works by Annibale Carracci (Bolognese, 1560 - 1609) and Domenichino (1581–-1641), artists whose classicizing tendencies would also inform Honthorst’s style. The contemporary Italian art critic Giulio Mancini noted that Honthorst was able to command high prices for his striking paintings, which decorated -

Title the Hands of Rubens: on Copies and Their Reception Author(S)

Title The Hands of Rubens: On Copies and Their Reception Author(s) Büttner, Nils Citation Kyoto Studies in Art History (2017), 2: 41-53 Issue Date 2017-04 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/229459 © Graduate School of Letters, Kyoto University and the Right authors Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 41 The Hands of Rubens: On Copies and Their Reception Nils Büttner Peter Paul Rubens had more than two hands. How else could he have created the enormous number of works still associated with his name? A survey of the existing paintings shows that almost all of his famous paintings exist in more than one version. It is notable that the copies of most of his paintings are very often contemporary, sometimes from his workshop. It is astounding even to see the enormous range of painterly qualities which they exhibit. The countless copies and replicas of his works contributed to increasing Rubens’s fame and immortalizing his name. Not all paintings connected to his name, however, were well suited to do the inventor of the compositions any credit. This resulted in a problem of productions “harmed his reputation (fit du tort à sa reputation).” 1 Joachim von Sandrart, a which already one of his first biographers, Roger de Piles, was aware: some of these 2 “Through his industriousness the City of Antwerpbiographer became who had an exceptional met Rubens art in schoolperson, in on which the other students hand, achieved saw the notable benefits perfection.” of copying3 Rubens’sAccordingly, style for gainingthe art production one of the inapprenticeships Antwerp: in Rubens’s workshop was in great demand. -

The Amsterdam Civic Guard Pieces Within and Outside the New Rijksmuseum Pt. IV

Volume 6, Issue 2 (Summer 2014) The Amsterdam Civic Guard Pieces within and Outside the New Rijksmuseum Pt. IV D. C. Meijer Jr., trans. Tom van der Molen Recommended Citation: D. C. Meijer Jr., “The Amsterdam Civic Guard Pieces Within and Outside the New Rijksmuseum Pt. IV,” trans. Tom van der Molen, JHNA 6:2 (Summer 2014) DOI:10.5092/jhna.2014.6.2.4 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/amsterdam-civic-guard-pieces-within-outside-new-rijksmu- seum-part-iv/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This is a revised PDF that may contain different page numbers from the previous version. Use electronic searching to locate passages. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 6:2 (Summer 2014) 1 THE AMSTERDAM CIVIC GUARD PIECES WITHIN AND OUTSIDE THE NEW RIJKSMUSEUM PT. IV D. C. Meijer Jr. (Tom van der Molen, translator) This fourth installment of D. C. Meijer Jr.’s article on Amsterdam civic guard portraits focuses on works by Thomas de Keyser and Joachim von Sandrart (Oud Holland 6 [1888]: 225–40). Meijer’s article was originally published in five in- stallments in the first few issues of the journal Oud Holland. For translations (also by Tom van der Molen) of the first two installments, see JHNA 5, no. 1 (Winter 2013). For the third installment, see JHNA 6, no. -

Between Academic Art and Guild Traditions 21

19 JULIA STROBL, INGEBORG SCHEMPER-SPARHOLZ, quently accompanied Philipp Jakob to Graz in 1733.2 MATEJ KLEMENČIČ The half-brothers Johann Georg Straub (1721–73) and Franz Anton (1726–74/6) were nearly a decade younger. There is evidence that in 1751 Johann Georg assisted at BETWEEN ACADEMIC ART AND Philipp Jakobs’s workshop in Graz before he married in Bad Radkersburg in 1753.3 His sculptural œuvre is GUILD TRADITIONS hardly traceable, and only the figures on the right-side altar in the Church of Our Lady in Bad Radkersburg (ca. 1755) are usually attributed to him.4 The second half- brother, Franz Anton, stayed in Zagreb in the 1760s and early 1770s; none of his sculptural output has been confirmed by archival sources so far. Due to stylistic similarities with his brother’s works, Doris Baričević attributed a number of anonymous sculptures from the 1760s to him, among them the high altar in Ludina The family of sculptors Johann Baptist, Philipp Jakob, and the pulpit in Kutina.5 Joseph, Franz Anton, and Johann Georg Straub, who worked in the eighteenth century on the territory of present-day Germany (Bavaria), Austria, Slovenia, Cro- STATE OF RESEARCH atia, and Hungary, derives from Wiesensteig, a small Bavarian enclave in the Swabian Alps in Württemberg. Due to his prominent position, Johann Baptist Straub’s Johann Ulrich Straub (1645–1706), the grandfather of successful career in Munich awoke more scholarly in- the brothers, was a carpenter, as was their father Jo- terest compared to his younger brothers, starting with hann Georg Sr (1674–1755) who additionally acted as his contemporary Johann Caspar von Lippert. -

Spur Der Arbeit. Oberfläche Und Werkprozess

MAGDALENA BUSHART, HENRIKE HAUG (HG.): SPUR DER ARBEIT. OBERFLÄCHE UND WERKPROZESS. ISBN 978-3-412-50388-8 © 2017 by BÖHLAU VERLAG GMBH & CIE, WIEN KÖLN WEIMAR Magdalena Bushart | Henrike Haug (Hg.) Spur der Arbeit Oberfläche und Werkprozess ELEKTRONISCHER SONDERDRUCK 2018 BÖHLAU VERLAG KÖLN WEIMAR WIEN DIESER eSONDERDRUCK DARF NUR ZU PERSÖNLICHEN ZWECKEN UND WEDER DIREKT NOCH INDIREKT FÜR ELEKTRONISCHE PUBLIKATIONEN DURCH DIE VERFASSERIN ODER DEN VERFASSER DES BEITRAGS GENUTZT WERDEN. MAGDALENA BUSHART, HENRIKE HAUG (HG.): SPUR DER ARBEIT. OBERFLÄCHE UND WERKPROZESS. ISBN 978-3-412-50388-8 © 2017 by BÖHLAU VERLAG GMBH & CIE, WIEN KÖLN WEIMAR Inhalt 7 Magdalena Bushart und Henrike Haug Spurensuche/Spurenlese Zur Sichtbarkeit von Arbeit im Werk 25 Bastian Eclercy Spuren im Gold Technik und Ästhetik des Goldgrunddekors in der toskanischen Dugentomalerei 39 Heiko Damm Imprimitur und Fingerspur Zu Luca Giordanos Londoner Hommage an Velázquez 65 Farbtafeln 81 Yannis Hadjinicolaou Contradictory Liveliness Painting as Process in the Work of Arent de Gelder and Christopher Paudiß 95 Christian Berger Edgar Degas’ Bildoberflächen als Experimentierfelder 111 Aleksandra Lipin´ska Alabasterskulptur zwischen sprezzatura und Verwandlung 127 Nicola Suthor (Non)Transparency in the Description of a Sketch Rembrandt’s Christ Carrying the Cross 145 Niccola Shearman Reversal of Values On the Woodblock and its Print in Weimar Germany 167 Ekaterina Petrova Von Index zu Ikon Transfigurationen der Arbeitsspur im zeichnerischen Werk von Auguste Rodin Inhalt I 5 DIESER eSONDERDRUCK DARF NUR ZU PERSÖNLICHEN ZWECKEN UND WEDER DIREKT NOCH INDIREKT FÜR ELEKTRONISCHE PUBLIKATIONEN DURCH DIE VERFASSERIN ODER DEN VERFASSER DES BEITRAGS GENUTZT WERDEN. MAGDALENA BUSHART, HENRIKE HAUG (HG.): SPUR DER ARBEIT. -

4 O C T Ob E R 2 015 to 17 Ja N U Ar Y 2

»GOVERT FLINCK 4 October 2015 to 17 January 2016 REFLECTING Museum Kurhaus Kleve – Ewald Mataré-Collection, HISTORY« Kleve / Germany ork Y ew N ollection, C eiden L he T 1643, , Self-portrait , GOVERT FLINCK of Kloveniers’ civic guards in Amsterdam. Today’s most well- most Today’s Amsterdam. in guards civic Kloveniers’ of have survived. have into present-day modes of perception. of modes present-day into A portraits for the Great Hall of the Kloveniersdoelen, the seat seat the Kloveniersdoelen, the of Hall Great the for portraits the fi rst works by Flinck with his signature signature his with Flinck by works rst fi the 1636 in Starting fascinating still-lifes of Juan Sanchez Cotàn, translating them them translating Cotàn, Sanchez Juan of still-lifes fascinating mong other works, Govert Flinck painted two of seven group group seven of two painted Flinck Govert works, other mong missions is not known. not is missions structure of historical painting in previous projects, such as the the as such projects, previous in painting historical of structure Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Rijksmuseum teacher, or whether his teacher voluntarily let him have com- have him let voluntarily teacher his whether or teacher, years, has already critically engaged with the aesthetics and and aesthetics the with engaged critically already has years, Rembrandt as shepherd as Rembrandt 1636 , , FLINCK GOVERT painting. Whether Flinck took business away from his former former his from away business took Flinck Whether painting. The artist Ori Gersht, who has been living in London for many many for London in living been has who Gersht, Ori artist The MAIN WORKS WORKS MAIN Rembrandt’s competitors, especially in the area of portrait portrait of area the in especially competitors, Rembrandt’s the essence of artistic freedom, juxtaposing his own position to it. -

Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory Thesis Claude Lorrain's Great Escape

Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory Thesis Claude Lorrain’s Great Escape: An Exploration into the Human Connection with Landscape Painting Hannah Anderson Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory, School of Art and Design Division of Art History New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University Alfred, New York 2020 Hannah Anderson, BS Jennifer Lyons, Thesis Advisor 1 Abstract: My thesis centers on the idea of the human connection towards landscape paintings by analyzing the seaport and coastal scenes by Baroque landscape painter, Claude Lorrain. Within these bodies of work I focus on ideas of escapism, visual pilgrimage, and virtual reality. My work will explore the questions of what escapism or a visual pilgrimage is, how a person can be drawn into a landscape painting, and whether or not the placement or orientation can impact how we interpret and feel about a work. I draw upon a wide variety of methodologies such as semiotics and psychoanalysis to frame my argument. 2 The scene is set, and all that is in sight is a dazzling body of water with a glimmering sunset surrounded by classical architecture. For a second, we are able to notice the chaotic scene that is happening around us but it’s hard to focus because we can’t keep our eyes off the light. It’s like this great, glowing beam that is pulling us closer and closer into the scene, making it hard to pay attention to anything else. Certainly, we are able to notice the people around us and that there is a more important event that is about to begin but it’s like everything has simply melted away and the only aspect we can keep an eye on is this warm, golden orb that shines down upon the sea. -

Introduction

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Netherlandish immigrant painters in Naples (1575-1654): Aert Mytens, Louis Finson, Abraham Vinck, Hendrick De Somer and Matthias Stom Osnabrugge, M.G.C. Publication date 2015 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Osnabrugge, M. G. C. (2015). Netherlandish immigrant painters in Naples (1575-1654): Aert Mytens, Louis Finson, Abraham Vinck, Hendrick De Somer and Matthias Stom. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:28 Sep 2021 INTRODUCTION ‘After that they completed their journey to Naples and saw the works of art there, and also the interesting phenomena at Pozzuoli. -

Dianakosslerovamlittthesis1988 Original C.Pdf

University of St Andrews Full metadata for this thesis is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by original copyright M.LITT. (ART GALLERY STUDIES) DISSERTATION AEGIDIDS SADELER'S ENGRAVINGS IN TM M OF SCOTLAND VOLUME I BY DIANA KOSSLEROVA DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF ST ANDREWS 1988 I, Diana Kosslerova, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 24 000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. date.?.0. /V. ?... signature of candidate; I was admitted as a candidate for the degree of M.Litt. in October 1985 the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St. Andrews between October 1985 and April 1988. date... ????... signature of candidate. I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of in the University of St. Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. datefV.Q. signature of supervisor, In submitting this thesis to the University of St. Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the work may be made and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. -

View, Worked Closely with Artemisia

which the .hlel lwd Sisenl fell far short. In the JHel Hnd ..S)senl the figures appear as light-an-dark silhouettes depriving the work of mood or atmosphere. The result is one of the least powerful pictures ,"vithin the oeuvre of Artemisia. In terms of anatomical depiction, the Detroit picture makes subtle advances over Artemisia's other pictures including the Uffizi Judith, the Penitent il-h{Rthilen. and the illinen'll. As for dating the Detroit painting, one should consider that it shows advancement over the above mentioned pictures. To determine a date for Artemisia's pictures, one cannot assume her work shows a linear progression of quality. But in the case of the Detroit Judith, the painting's Caravaggesque lighting and sophisticated space suggest a date in the late part of her Roman years, just before she left for Naples. However, of A.rtemisia's output in Rome, in fact, nothing except the Oonl111oniere and the Burghley 5'U}'iWnH is certainly known. Bissell hypothesized that the Capodimonte Jud.1th Rnd Holofernes might belong to Artemisia's Roman period, but he was not aware of the penlimenli in this picture which led Garrard and later scholars to a different conclusion. 1 Garrard gives it a relatively early date of ca. 1612-13, well prior the date usually hypothesized for the Uffizi verSiOn, a Florentine picture, whih as he have seen, it appears to predate. 1Garrard , 1989, 32 and n. 35. The X rays were made at her request in 1983 at the National Gallery of "'lash D C See p. -

Introduction

Volume 12, Issue 1 (Winter 2020) Introduction Jasper Hillegers, Elmer Kolfin, Marrigje Rikken, Eric Jan Sluijter [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Recommended Citation: Jasper Hillegers, Elmer Kolfin, Marrigje Rikken, Eric Jan Sluijter, “Introduction,” Journal of Histo- rians of Netherlandish Art 12:1 (Winter 2020) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2020.12.1.1 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/introduction/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 Introduction Jasper Hillegers, Elmer Kolfin, Marrigje Rikken, Eric Jan Sluijter In 2017-2018, the first exhibition ever devoted to the oeuvre of Gerard de Lairesse – in his own time one of the most celebrated Netherlandish artists – was held in the Rijksmuseum Twenthe. It was appropriately called: Eindelijk! De Lairesse (Finally! De Lairesse). At the close of the exhibition, a two-day symposium took place at the Rijksmuseum Twenthe in Enschede and the RKD-Netherlands Institute for Art History in The Hague, in collaboration with the University of Amsterdam. The symposium formed the starting point for this special issue of JHNA. The issue presents new insights into Gerard de Lairesse’s artistic development, subject matter, workshop practice, and technique. This special issue has been guest edited by Jasper Hillegers, Research Curator, Salomon Lilian Gallery, Amsterdam; Elmer Kol- fin, Associate Professor of Art History, University of Amsterdam; Marrigje Rikken, Head of Collections, Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem; Eric Jan Sluijter, Emeritus Professor of Art History, University of Amsterdam.