Title the Hands of Rubens: on Copies and Their Reception Author(S)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Grote Rubens Atlas

DE GROTE RUBENS ATLAS GUNTER HAUSPIE DUITSLAND INHOUD 1568-1589 12-23 13 VLUCHT NAAR KEULEN 13 HUISARREST IN SIEGEN 14 GEBOORTE VAN PETER PAUL ANTWERPEN 15 SIEGEN 16 JEUGD IN KEULEN 1561-1568 17 KEULEN 20 RUBENS’ SCHILDERIJ 10-11 10 WELGESTELDE OUDERS IN DE SANKT PETER 10 ONRUST IN ANTWERPEN 21 NEDERLANDSE ENCLAVE IN KEULEN 11 SCHRIKBEWIND VAN ALVA 22 RUBENS IN HET WALLRAF- RICHARTZ-MUSEUM 23 TERUGKEER NAAR ANTWERPEN 1561 1568 1577 LEEFTIJD 0 1 2 3 4 ITALIË 1600-1608 32-71 33 OVER DE ALPEN 53 OP MISSIE NAAR SPANJE 33 VIA VENETIË NAAR MANTUA 54 EEN ZWARE TOCHT 35 GLORIERIJK MANTUA 54 OPLAPWERK IN VALLADOLID 38 LAGO DI MEZZO 55 VALLADOLID 39 MANTUA IN RUBENS’ TIJD 56 PALACIO REAL 40 CASTELLO DI SAN GIORGIO 57 OVERHANDIGING VAN DE GESCHENKEN 41 PALAZZO DUCALE 57 HERTOG VAN LERMA 42 BASILICA DI SANT’ANDREA 59 GEEN SPAANSE HOFSCHILDER 42 IL RIO 59 TWEEDE VERBLIJF IN ROME 42 HUIS VAN GIULIO ROMANO 59 CHIESA NUOVA 42 HUIS VAN ANDREA MANTEGNA 60 DE GENUESE ELITE 43 PALAZZO TE 61 INSPIREREND GENUA 44 MANTUAANS MEESTERWERK 65 DE PALAZZI VAN GENUA 48 HUWELIJK VAN MARIA DE’ MEDICI 67 EEN LAATSTE KEER ROME IN FIRENZE 67 TERUGKEER NAAR ANTWERPEN 49 EERSTE VERBLIJF IN ROME 68 RUBENS IN ROME 49 SANTA CROCE IN GERUSALEMME 70 STEDEN MET SCHILDERIJEN UIT 51 VIA EEN OMWEG NAAR GRASSE RUBENS’ ITALIAANSE PERIODE 52 VERONA EN PADUA 1600 1608 VLAAMSE MEESTERS 4 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 ANTWERPEN 1589-1600 24-31 25 TERUG IN ANTWERPEN 25 STAD IN VERVAL 26 UITMUNTEND STUDENT 27 DE JEUGDJAREN IN ANTWERPEN 28 GOEDE MANIEREN LEREN 28 DE ROEP VAN DE KUNST 28 -

The Rubenianum Quarterly

2016 The Rubenianum Quarterly 1 Announcing project Collection Ludwig Burchard II Dear friends, colleagues and benefactors, We are pleased to announce that through a generous donation the Rubenianum will be I have the pleasure to inform you of the able to dedicate another project to Ludwig Burchard’s scholarly legacy. The project entails imminent publication of the first part of two main components, both building on previous undertakings that have been carried the mythology volumes in the Corpus out to preserve the Rubenianum’s core collection and at the same time ensure enhanced Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard. The accessibility to the scholarly community of the wealth of Rubens documentation. Digitizing the Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard, launched in 2013 and successfully two volumes are going to press as we extended until May 2016, will be continued for all Corpus volumes published before 2003, speak and will be truly impressive. abiding by the moving wall of 15 years, that was agreed upon with Brepols Publishers, for the Consisting of nearly 1000 pages and over years 2016–18. 400 images, they will be a monumental The second and larger component of the project builds on the enterprise titled A treasure addition to our ever-growing catalogue trove of study material. Disclosure and valorization of the Collection Ludwig Burchard, raisonné of Rubens’s oeuvre and constitute successfully executed in 2014–15. An archival description of Rubenianum objects originating from Burchard’s library and documentation has since allowed for a virtual reconstruction a wonderful Easter present. of the expert’s scholarly legacy. Much emphasis was placed on the Rubens files during In the meantime, volume xix, 4 on Peter this project, while the collection contains many other resources that are of considerable Paul Rubens’s many portrait copies, importance to Rubens research. -

The Wallace Collection — Rubens Reuniting the Great Landscapes

XT H E W ALLACE COLLECTION RUBENS: REUNITING THE GREAT LANDSCAPES • Rubens’s two great landscape paintings reunited for the first time in 200 years • First chance to see the National Gallery painting after extensive conservation work • Major collaboration between the National Gallery and the Wallace Collection 3 June - 15 August 2021 #ReunitingRubens In partnership with VISITFLANDERS This year, the Wallace Collection will reunite two great masterpieces of Rubens’s late landscape painting: A View of Het Steen in the Early Morning and The Rainbow Landscape. Thanks to an exceptional loan from the National Gallery, this is the first time in two hundred years that these works, long considered to be companion pieces, will be seen together. This m ajor collaboration between the Wallace Collection and the National Gallery was initiated with the Wallace Collection’s inaugural loan in 2019 of Titian’s Perseus and Andromeda, enabling the National Gallery to complete Titian’s Poesie cycle for the first time in 400 years for their exhibition Titian: Love, Desire, Death. The National Gallery is now making an equally unprecedented reciprocal loan to the Wallace Collection, lending this work for the first time, which will reunite Rubens’s famous and very rare companion pair of landscape paintings for the first time in 200 years. This exhibition is also the first opportunity for audiences to see the National Gallery painting newly cleaned and conserved, as throughout 2020 it has been the focus of a major conservation project specifically in preparation for this reunion. The pendant pair can be admired in new historically appropriate, matching frames, also created especially for this exhibition. -

HNA April 11 Cover-Final.Indd

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 28, No. 1 April 2011 Jacob Cats (1741-1799), Summer Landscape, pen and brown ink and wash, 270-359 mm. Hamburger Kunsthalle. Photo: Christoph Irrgang Exhibited in “Bruegel, Rembrandt & Co. Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850”, June 17 – September 11, 2011, on the occasion of the publication of Annemarie Stefes, Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850, Kupferstichkabinett der Hamburger Kunsthalle (see under New Titles) HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone/Fax: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President - Stephanie Dickey (2009–2013) Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Vice-President - Amy Golahny (2009–2013) Lycoming College Williamsport, PA 17701 Treasurer - Rebecca Brienen University of Miami Art & Art History Department PO Box 248106 Coral Gables FL 33124-2618 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Board Members Contents Dagmar Eichberger (2008–2012) HNA News ............................................................................1 Wayne Franits (2009–2013) Matt Kavaler (2008–2012) Personalia ............................................................................... 2 Henry Luttikhuizen (2009 and 2010–2014) Exhibitions -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

OLD MASTER PAINTINGS Wednesday 9 December 2015

OLD MASTER PAINTINGS Wednesday 9 December 2015 BONHAMS OLD MASTERS DEPARTMENT Andrew McKenzie Caroline Oliphant Brian Koetser Director, Head of Department, Group Head of Pictures Consultant, London London London London – – – Lisa Greaves Archie Parker Poppy Harvey-Jones Department Director Senior Specialist Junior Specialist London London London – – – Alexandra Frost Mark Fisher Madalina Lazen Administrator, Director, European Paintings, Senior Specialist, European Paintings Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams 1793 Ltd Directors Bonhams UK Ltd Directors Registered No. 4326560 Robert Brooks Co-Chairman, Colin Sheaf Chairman, Jonathan Baddeley, Gordon McFarlan, Andrew McKenzie, London Los Angeles New York Registered Office: Montpelier Galleries Malcolm Barber Co-Chairman, Antony Bennett, Matthew Bradbury, Simon Mitchell, Jeff Muse, Mike Neill, Montpelier Street, London SW7 1HH Colin Sheaf Deputy Chairman, Lucinda Bredin, Harvey Cammell, Simon Cottle, Charlie O’Brien, Giles Peppiatt, Peter Rees, Matthew Girling CEO, Andrew Currie, Paul Davidson, Jean Ghika, Iain Rushbrook, John Sandon, Tim Schofield, – – – +44 (0) 20 7393 3900 Patrick Meade Group Vice Chairman, Charles Graham-Campbell, Miranda Leslie, Veronique Scorer, James Stratton, Roger Tappin, +44 (0) 20 7393 3905 fax Geoffrey Davies, Jonathan Horwich, Richard Harvey, Robin Hereford, Asaph Hyman, Ralph Taylor, Shahin Virani, David Williams, James Knight, Caroline Oliphant. David Johnson, Charles Lanning, Michael Wynell-Mayow, Suzannah Yip. OLD MASTER PAINTINGS Wednesday 9 December 2015, at -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Culturele ondernemers in de Gouden Eeuw: De artistieke en sociaal- economische strategieën van Jacob Backer, Govert Flinck, Ferdinand Bol en Joachim von Sandrart Kok, E.E. Publication date 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kok, E. E. (2013). Culturele ondernemers in de Gouden Eeuw: De artistieke en sociaal- economische strategieën van Jacob Backer, Govert Flinck, Ferdinand Bol en Joachim von Sandrart. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:03 Oct 2021 Summary Jacob Backer (1608/9-1651), Govert Flinck (1615-1660), Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680), and Joachim von Sandrart (1606-1688) belong among the most successful portrait and history painters of the Golden Age in Amsterdam. -

Webfile121848.Pdf

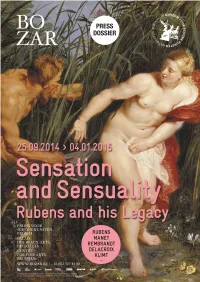

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

Honthorst, Gerrit Van Also Known As Honthorst, Gerard Van Gherardo Della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Honthorst, Gerrit van Also known as Honthorst, Gerard van Gherardo della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656 BIOGRAPHY Gerrit van Honthorst was born in Utrecht in 1592 to a large Catholic family. His father, Herman van Honthorst, was a tapestry designer and a founding member of the Utrecht Guild of St. Luke in 1611. After training with the Utrecht painter Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), Honthorst traveled to Rome, where he is first documented in 1616.[1] Honthorst’s trip to Rome had an indelible impact on his painting style. In particular, Honthorst looked to the radical stylistic and thematic innovations of Caravaggio (Roman, 1571 - 1610), adopting the Italian painter’s realism, dramatic chiaroscuro lighting, bold colors, and cropped compositions. Honthorst’s distinctive nocturnal settings and artificial lighting effects attracted commissions from prominent patrons such as Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1577–1633), Cosimo II, the Grand Duke of Tuscany (1590–1621), and the Marcheses Benedetto and Vincenzo Giustiniani (1554–1621 and 1564–1637). He lived for a time in the Palazzo Giustiniani in Rome, where he would have seen paintings by Caravaggio, and works by Annibale Carracci (Bolognese, 1560 - 1609) and Domenichino (1581–-1641), artists whose classicizing tendencies would also inform Honthorst’s style. The contemporary Italian art critic Giulio Mancini noted that Honthorst was able to command high prices for his striking paintings, which decorated -

The Leiden Collection

Emperor Commodus as Hercules ca. 1599–1600 and as a Gladiator oil on panel Peter Paul Rubens 65.5 x 54.4 cm Siegen 1577 – 1640 Antwerp PR-101 © 2017 The Leiden Collection Emperor Commodus as Hercules and as a Gladiator Page 2 of 11 How To Cite Van Tuinen, Ilona. "Emperor Commodus as Hercules and as a Gladiator." InThe Leiden Collection Catalogue. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. New York, 2017. https://www.theleidencollection.com/archive/. This page is available on the site's Archive. PDF of every version of this page is available on the Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. Archival copies will never be deleted. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2017 The Leiden Collection Emperor Commodus as Hercules and as a Gladiator Page 3 of 11 Peter Paul Rubens painted this bold, bust-length image of the eccentric Comparative Figures and tyrannical Roman emperor Commodus (161–92 A.D.) within an illusionistic marble oval relief. In stark contrast to his learned father Marcus Aurelius (121–80 A.D.), known as “the perfect Emperor,” Commodus, who reigned from 180 until he was murdered on New Year’s Eve of 192 at the age of 31, proudly distinguished himself by his great physical strength.[1] Toward the end of his life, Commodus went further than any of his megalomaniac predecessors, including Nero, and identified himself with Hercules, the superhumanly strong demigod of Greek mythology famous for slaughtering wild animals and monsters with his bare hands. According to the contemporary historian Herodian of Antioch (ca. -

Valuing Congestion Costs in Museums

Valuing congestion costs in small museums: the case of the Rubenshuis Museum in Antwerp Juliana Salazar Borda Master Cultural Economics & Cultural Entrepreneurship Faculteit der Historische en Kunstwetenschappen Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam [email protected] Supervisor: Dr. F.R.R. Vermeylen Second Reader: Dr. A. Klamer 2007 Summary Within the methodological framework of Contingent Valuation (CV), the purpose of this research was to find in the Rubenshuis Museum the ‘congestion cost’ or the amount visitors are willing to pay in order to avoid too many people inside. A number of 200 site interviews with museum visitors, either entering or leaving the museum, were made. The analysis of the results showed a strong tendency of visitors to prefer not congested situations. However, their WTP more for the ticket was low (€1.33 in average). It was also found that if visitors were women, were older, were better educated and had a bad experience at the museum, the WTP went up. In addition, those visitors who were in their way out of the museum showed a higher WTP than those ones who were in their way in. Other options to diminish congestion were also asked to visitors. Extra morning and night opening hours were the most popular ones among the sample, which is an alert to the museum to start thinking in improving its services. The Rubenshuis Museum is a remarkable example of how congestion can be handled in order to have a better experience. That was reflected in the answers visitors gave about congestion. In general, even if the museum had a lot of attendance, people were very pleased with the experience and they were amply capable to enjoy the collection. -

Annual Report 2004

mma BOARD OF TRUSTEES Richard C. Hedreen (as of 30 September 2004) Eric H. Holder Jr. Victoria P. Sant Raymond J. Horowitz Chairman Robert J. Hurst Earl A. Powell III Alberto Ibarguen Robert F. Erburu Betsy K. Karel Julian Ganz, Jr. Lmda H. Kaufman David 0. Maxwell James V. Kimsey John C. Fontaine Mark J. Kington Robert L. Kirk Leonard A. Lauder & Alexander M. Laughlin Robert F. Erburu Victoria P. Sant Victoria P. Sant Joyce Menschel Chairman President Chairman Harvey S. Shipley Miller John W. Snow Secretary of the Treasury John G. Pappajohn Robert F. Erburu Sally Engelhard Pingree Julian Ganz, Jr. Diana Prince David 0. Maxwell Mitchell P. Rales John C. Fontaine Catherine B. Reynolds KW,< Sharon Percy Rockefeller Robert M. Rosenthal B. Francis Saul II if Robert F. Erburu Thomas A. Saunders III Julian Ganz, Jr. David 0. Maxwell Chairman I Albert H. Small John W. Snow Secretary of the Treasury James S. Smith Julian Ganz, Jr. Michelle Smith Ruth Carter Stevenson David 0. Maxwell Roselyne C. Swig Victoria P. Sant Luther M. Stovall John C. Fontaine Joseph G. Tompkins Ladislaus von Hoffmann John C. Whitehead Ruth Carter Stevenson IJohn Wilmerding John C. Fontaine J William H. Rehnquist Alexander M. Laughlin Dian Woodner ,id Chief Justice of the Robert H. Smith ,w United States Victoria P. Sant John C. Fontaine President Chair Earl A. Powell III Frederick W. Beinecke Director Heidi L. Berry Alan Shestack W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Deputy Director Elizabeth Cropper Melvin S. Cohen Dean, Center for Advanced Edwin L. Cox Colin L. Powell John W.