Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking Dutch Art Seriously: Now and Next? Author(S): MARIËT WESTERMANN Source: Studies in the History of Art, Vol

National Gallery of Art Taking Dutch Art Seriously: Now and Next? Author(s): MARIËT WESTERMANN Source: Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 74, Symposium Papers LI: Dialogues in Art History, from Mesopotamian to Modern: Readings for a New Century (2009), pp. 258-270 Published by: National Gallery of Art Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42622727 Accessed: 11-04-2020 11:41 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42622727?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms National Gallery of Art is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Studies in the History of Art This content downloaded from 85.72.204.160 on Sat, 11 Apr 2020 11:41:16 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms /';-=09 )(8* =-0/'] This content downloaded from 85.72.204.160 on Sat, 11 Apr 2020 11:41:16 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms MARIËT WESTERMANN New York University Taking Dutch Art Seriously : Now and Nextl vative, staid, respectable discipline, some- posium with mounting anxiety. -

The Infancy of Jesus and Religious Painting by Gerard De Lairesse

Volume 12, Issue 1 (Winter 2020) The Infancy of Jesus and Religious Painting by Gerard de Lairesse Robert Schillemans [email protected] Recommended Citation: Robert Schillemans, “The Infancy of Jesus and Religious Painting by Gerard de Lairesse,” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 12:1 (Winter 2020) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2020.12.1.6 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/the-infancy-of-jesus-and-religious-painting-by-gerard-de- lairesse/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 The Infancy of Jesus and Religious Painting by Gerard de Lairesse Robert Schillemans Just after his arrival in Amsterdam, Lairesse painted an impressive series of six paintings on the infancy of Jesus. This article argues that the series must have been made for the Catholic South, presumably for an ecclesiastical institute in Liège or vicinity. Its character connects his painted cycle with the Counter-Reformation. Lairesse involves the viewer closely with the religious content, encouraging meditation, contemplation, and reflection. Despite his flight to Protestant Amsterdam, and his joining (as a full member) the Francophone Walloon Reformed Church, Lairesse continued to maintain warm links with the highest circles in his native Liège. In the Infancy of Jesus, Lairesse thoroughly studied the engravings of Goltzius’s Life of Mary (as well as Rubens and Rembrandt). -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Culturele ondernemers in de Gouden Eeuw: De artistieke en sociaal- economische strategieën van Jacob Backer, Govert Flinck, Ferdinand Bol en Joachim von Sandrart Kok, E.E. Publication date 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kok, E. E. (2013). Culturele ondernemers in de Gouden Eeuw: De artistieke en sociaal- economische strategieën van Jacob Backer, Govert Flinck, Ferdinand Bol en Joachim von Sandrart. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:03 Oct 2021 Summary Jacob Backer (1608/9-1651), Govert Flinck (1615-1660), Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680), and Joachim von Sandrart (1606-1688) belong among the most successful portrait and history painters of the Golden Age in Amsterdam. -

Webfile121848.Pdf

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

Honthorst, Gerrit Van Also Known As Honthorst, Gerard Van Gherardo Della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Honthorst, Gerrit van Also known as Honthorst, Gerard van Gherardo della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656 BIOGRAPHY Gerrit van Honthorst was born in Utrecht in 1592 to a large Catholic family. His father, Herman van Honthorst, was a tapestry designer and a founding member of the Utrecht Guild of St. Luke in 1611. After training with the Utrecht painter Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), Honthorst traveled to Rome, where he is first documented in 1616.[1] Honthorst’s trip to Rome had an indelible impact on his painting style. In particular, Honthorst looked to the radical stylistic and thematic innovations of Caravaggio (Roman, 1571 - 1610), adopting the Italian painter’s realism, dramatic chiaroscuro lighting, bold colors, and cropped compositions. Honthorst’s distinctive nocturnal settings and artificial lighting effects attracted commissions from prominent patrons such as Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1577–1633), Cosimo II, the Grand Duke of Tuscany (1590–1621), and the Marcheses Benedetto and Vincenzo Giustiniani (1554–1621 and 1564–1637). He lived for a time in the Palazzo Giustiniani in Rome, where he would have seen paintings by Caravaggio, and works by Annibale Carracci (Bolognese, 1560 - 1609) and Domenichino (1581–-1641), artists whose classicizing tendencies would also inform Honthorst’s style. The contemporary Italian art critic Giulio Mancini noted that Honthorst was able to command high prices for his striking paintings, which decorated -

De Lairesse on the Theory and Practice Lyckle De Vries

NEW PUBLICATION How to create beauty De Lairesse on the theory and practice Lyckle de Vries Gerard de Lairesse (1641-1711) was the most of drawing (1701) and a manual on painting successful Dutch painter of his time, admired (1707). The latter, the Groot Schilderboek, is by the patricians of Amsterdam and the court the subject of this fine new study by art histo- of William III of Orange. An eighteenth-cen- rian Lyckle de Vries. Among De Vries’s earlier tury critic called him ‘undoubtedly the greatest publications are a monograph and a number genius there ever was in painting’. After a cen- of articles on De Lairesse, his paintings, his tury of neglect his rehabilitation began in 1970 work for the theatre and his writings. when the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum acquired a De Vries found that Gerard de Lairesse’s series of his monumental grisaille paintings. In treatise (‘offering thorough instruction in an international exhibition (Cologne, Cassel, the art of painting in all its aspects’) is not Dordrecht 2007) he was presented as the primarily a discourse on the theory of art, leading artist of his time, the last quarter of the but a practical manual for young painters. seventeenth century. As part of this rehabili- It probably was meant as a course for self tation process, interest in his writings also in- study. In view of the fact that the author was creased. De Lairesse wrote a booklet on the art highly critical of the training methods of his contemporaries, it is not so surprising that he put pen to paper to explain how the mind and hand of a young painter should cooperate in order to turn a mental image into a beautiful picture. -

Title the Hands of Rubens: on Copies and Their Reception Author(S)

Title The Hands of Rubens: On Copies and Their Reception Author(s) Büttner, Nils Citation Kyoto Studies in Art History (2017), 2: 41-53 Issue Date 2017-04 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/229459 © Graduate School of Letters, Kyoto University and the Right authors Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 41 The Hands of Rubens: On Copies and Their Reception Nils Büttner Peter Paul Rubens had more than two hands. How else could he have created the enormous number of works still associated with his name? A survey of the existing paintings shows that almost all of his famous paintings exist in more than one version. It is notable that the copies of most of his paintings are very often contemporary, sometimes from his workshop. It is astounding even to see the enormous range of painterly qualities which they exhibit. The countless copies and replicas of his works contributed to increasing Rubens’s fame and immortalizing his name. Not all paintings connected to his name, however, were well suited to do the inventor of the compositions any credit. This resulted in a problem of productions “harmed his reputation (fit du tort à sa reputation).” 1 Joachim von Sandrart, a which already one of his first biographers, Roger de Piles, was aware: some of these 2 “Through his industriousness the City of Antwerpbiographer became who had an exceptional met Rubens art in schoolperson, in on which the other students hand, achieved saw the notable benefits perfection.” of copying3 Rubens’sAccordingly, style for gainingthe art production one of the inapprenticeships Antwerp: in Rubens’s workshop was in great demand. -

The Amsterdam Civic Guard Pieces Within and Outside the New Rijksmuseum Pt. IV

Volume 6, Issue 2 (Summer 2014) The Amsterdam Civic Guard Pieces within and Outside the New Rijksmuseum Pt. IV D. C. Meijer Jr., trans. Tom van der Molen Recommended Citation: D. C. Meijer Jr., “The Amsterdam Civic Guard Pieces Within and Outside the New Rijksmuseum Pt. IV,” trans. Tom van der Molen, JHNA 6:2 (Summer 2014) DOI:10.5092/jhna.2014.6.2.4 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/amsterdam-civic-guard-pieces-within-outside-new-rijksmu- seum-part-iv/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This is a revised PDF that may contain different page numbers from the previous version. Use electronic searching to locate passages. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 6:2 (Summer 2014) 1 THE AMSTERDAM CIVIC GUARD PIECES WITHIN AND OUTSIDE THE NEW RIJKSMUSEUM PT. IV D. C. Meijer Jr. (Tom van der Molen, translator) This fourth installment of D. C. Meijer Jr.’s article on Amsterdam civic guard portraits focuses on works by Thomas de Keyser and Joachim von Sandrart (Oud Holland 6 [1888]: 225–40). Meijer’s article was originally published in five in- stallments in the first few issues of the journal Oud Holland. For translations (also by Tom van der Molen) of the first two installments, see JHNA 5, no. 1 (Winter 2013). For the third installment, see JHNA 6, no. -

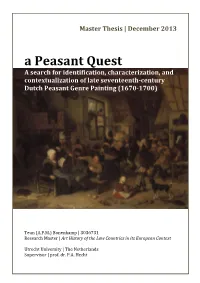

Thesis | December 2013

Master Thesis | December 2013 a Peasant Quest A search for identification, characterization, and contextualization of late seventeenth-century Dutch Peasant Genre Painting (1670-1700) Teun (A.P.M.) Bonenkamp | 3036731 Research Master | Art History of the Low Countries in its European Context Utrecht University | The Netherlands Supervisor | prof. dr. P.A. Hecht Table of contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Defining the subject ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Structure ........................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 1 | Peasant genre painting 1600-1670 .................................................................................... 8 Adriaen Brouwer (1605/06-1638) ....................................................................................................................... 9 Adriaen van Ostade (1610-1685) ........................................................................................................................ 11 In Van Ostade’s footsteps ........................................................................................................................................ 13 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Between Academic Art and Guild Traditions 21

19 JULIA STROBL, INGEBORG SCHEMPER-SPARHOLZ, quently accompanied Philipp Jakob to Graz in 1733.2 MATEJ KLEMENČIČ The half-brothers Johann Georg Straub (1721–73) and Franz Anton (1726–74/6) were nearly a decade younger. There is evidence that in 1751 Johann Georg assisted at BETWEEN ACADEMIC ART AND Philipp Jakobs’s workshop in Graz before he married in Bad Radkersburg in 1753.3 His sculptural œuvre is GUILD TRADITIONS hardly traceable, and only the figures on the right-side altar in the Church of Our Lady in Bad Radkersburg (ca. 1755) are usually attributed to him.4 The second half- brother, Franz Anton, stayed in Zagreb in the 1760s and early 1770s; none of his sculptural output has been confirmed by archival sources so far. Due to stylistic similarities with his brother’s works, Doris Baričević attributed a number of anonymous sculptures from the 1760s to him, among them the high altar in Ludina The family of sculptors Johann Baptist, Philipp Jakob, and the pulpit in Kutina.5 Joseph, Franz Anton, and Johann Georg Straub, who worked in the eighteenth century on the territory of present-day Germany (Bavaria), Austria, Slovenia, Cro- STATE OF RESEARCH atia, and Hungary, derives from Wiesensteig, a small Bavarian enclave in the Swabian Alps in Württemberg. Due to his prominent position, Johann Baptist Straub’s Johann Ulrich Straub (1645–1706), the grandfather of successful career in Munich awoke more scholarly in- the brothers, was a carpenter, as was their father Jo- terest compared to his younger brothers, starting with hann Georg Sr (1674–1755) who additionally acted as his contemporary Johann Caspar von Lippert. -

Spur Der Arbeit. Oberfläche Und Werkprozess

MAGDALENA BUSHART, HENRIKE HAUG (HG.): SPUR DER ARBEIT. OBERFLÄCHE UND WERKPROZESS. ISBN 978-3-412-50388-8 © 2017 by BÖHLAU VERLAG GMBH & CIE, WIEN KÖLN WEIMAR Magdalena Bushart | Henrike Haug (Hg.) Spur der Arbeit Oberfläche und Werkprozess ELEKTRONISCHER SONDERDRUCK 2018 BÖHLAU VERLAG KÖLN WEIMAR WIEN DIESER eSONDERDRUCK DARF NUR ZU PERSÖNLICHEN ZWECKEN UND WEDER DIREKT NOCH INDIREKT FÜR ELEKTRONISCHE PUBLIKATIONEN DURCH DIE VERFASSERIN ODER DEN VERFASSER DES BEITRAGS GENUTZT WERDEN. MAGDALENA BUSHART, HENRIKE HAUG (HG.): SPUR DER ARBEIT. OBERFLÄCHE UND WERKPROZESS. ISBN 978-3-412-50388-8 © 2017 by BÖHLAU VERLAG GMBH & CIE, WIEN KÖLN WEIMAR Inhalt 7 Magdalena Bushart und Henrike Haug Spurensuche/Spurenlese Zur Sichtbarkeit von Arbeit im Werk 25 Bastian Eclercy Spuren im Gold Technik und Ästhetik des Goldgrunddekors in der toskanischen Dugentomalerei 39 Heiko Damm Imprimitur und Fingerspur Zu Luca Giordanos Londoner Hommage an Velázquez 65 Farbtafeln 81 Yannis Hadjinicolaou Contradictory Liveliness Painting as Process in the Work of Arent de Gelder and Christopher Paudiß 95 Christian Berger Edgar Degas’ Bildoberflächen als Experimentierfelder 111 Aleksandra Lipin´ska Alabasterskulptur zwischen sprezzatura und Verwandlung 127 Nicola Suthor (Non)Transparency in the Description of a Sketch Rembrandt’s Christ Carrying the Cross 145 Niccola Shearman Reversal of Values On the Woodblock and its Print in Weimar Germany 167 Ekaterina Petrova Von Index zu Ikon Transfigurationen der Arbeitsspur im zeichnerischen Werk von Auguste Rodin Inhalt I 5 DIESER eSONDERDRUCK DARF NUR ZU PERSÖNLICHEN ZWECKEN UND WEDER DIREKT NOCH INDIREKT FÜR ELEKTRONISCHE PUBLIKATIONEN DURCH DIE VERFASSERIN ODER DEN VERFASSER DES BEITRAGS GENUTZT WERDEN. MAGDALENA BUSHART, HENRIKE HAUG (HG.): SPUR DER ARBEIT.