Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecce Accoglie Caravaggio

LECCE ACCOGLIE CARAVAGGIO LECCE ACCOGLIE CARAVAGGIO (DI MICHELE CUPPONE) Mai così strettamente legate, mistero e opera di un Caravaggio errante nel meridione in cerca di riscatto, approdano dopo quattro secoli in terra salentina. Da sempre paese di accoglienza, Lecce si prepara alla stagione estiva ospitando in primo luogo l'illustre lombardo che, nelle più disparate celebrazioni di quest’anno, forse un po' inaspettatamente scopre a sua volta una città d'arte e capitale della cultura degna del suo talento. Qui sono di certo le sfavillanti e fastose architetture barocche l'episodio artistico di maggior pregio, in un territorio che non lesina importanti testimonianze di altri periodi storico-artistici: preistoria e protostoria, età messapica e romana, bizantina e normanna, rinascimentale e manierista, tardo manierista e barocca appunto. Frapposta e sovrapposta a queste ultime due, la vicenda del caravaggismo ebbe i suoi echi anche qui; allora si era al tempo dei Vicerè spagnoli, e la Napoli nella quale operò prolificamente il Merisi era il naturale punto di riferimento e centro di irradiazione di impulsi artistici per, nella fattispecie, i pittori locali. Nel capoluogo salentino, come hanno ricostruito gli studi di Antonio Cassiano e Pierluigi Leone de Castris, si trasferì, praticamente all’indomani della morte di Caravaggio, il partenopeo Paolo Finoglio, che veicolò il verbo caravaggesco di cui a Napoli fu uno dei primi seguaci; teneva a mente, oltre alle opere del Lombardo, che lì soggiornava negli stessi anni, quelle del suo più grande interprete napoletano Battistello Caracciolo o di un Carlo Sellitto, o ancora di pittori tardomanieristi che conobbero una, magari anche breve, stagione caravaggesca e naturalistica: Filippo Vitale e Ippolito Borghese. -

Kingston Lacy Illustrated List of Pictures K Introduction the Restoration

Kingston Lacy Illustrated list of pictures Introduction ingston Lacy has the distinction of being the however, is a set of portraits by Lely, painted at K gentry collection with the earliest recorded still the apogee of his ability, that is without surviving surviving nucleus – something that few collections rival anywhere outside the Royal Collection. Chiefly of any kind in the United Kingdom can boast. When of members of his own family, but also including Ralph – later Sir Ralph – Bankes (?1631–1677) first relations (No.16; Charles Brune of Athelhampton jotted down in his commonplace book, between (1630/1–?1703)), friends (No.2, Edmund Stafford May 1656 and the end of 1658, a note of ‘Pictures in of Buckinghamshire), and beauties of equivocal my Chamber att Grayes Inne’, consisting of a mere reputation (No.4, Elizabeth Trentham, Viscountess 15 of them, he can have had little idea that they Cullen (1640–1713)), they induced Sir Joshua would swell to the roughly 200 paintings that are Reynolds to declare, when he visited Kingston Hall at Kingston Lacy today. in 1762, that: ‘I never had fully appreciated Sir Peter That they have done so is due, above all, to two Lely till I had seen these portraits’. later collectors, Henry Bankes II, MP (1757–1834), Although Sir Ralph evidently collected other – and his son William John Bankes, MP (1786–1855), but largely minor pictures – as did his successors, and to the piety of successive members of the it was not until Henry Bankes II (1757–1834), who Bankes family in preserving these collections made the Grand Tour in 1778–80, and paid a further virtually intact, and ultimately leaving them, in the visit to Rome in 1782, that the family produced astonishingly munificent bequest by (Henry John) another true collector. -

Gallery Baroque Art in Italy, 1600-1700

Gallery Baroque Art in Italy, 1600-1700 The imposing space and rich color of this gallery reflect the Baroque taste for grandeur found in the Italian palaces and churches of the day. Dramatic and often monumental, this style attested to the power and prestige of the individual or institution that commissioned the works of art. Spanning the 17th century, the Baroque period was a dynamic age of invention, when many of the foundations of the modern world were laid. Scientists had new instruments at their disposal, and artists discovered new ways to interpret ancient themes. The historical and contemporary players depicted in these painted dramas exhibit a wider range of emotional and spiritual conditions. Artists developed a new regard for the depiction of space and atmosphere, color and light, and the human form. Two major stylistic trends dominated the art of this period. The first stemmed from the revolutionary naturalism of the Roman painter, Caravaggio, who succeeded in fusing intense physical observations with a profound sense of drama, achieved largely through his chiaroscuro, or use of light and shadow. The second trend was inspired by the Bolognese painter, Annibale Carracci, and his school, which aimed to temper the monumental classicism of Raphael with the optical naturalism of Titian. The expressive nature of Carracci and his followers eventually developed into the imaginative and extravagant style known as the High Baroque. The Docent Collections Handbook 2007 Edition Niccolò de Simone Flemish, active 1636-1655 in Naples Saint Sebastian, c. 1636-40 Oil on canvas Bequest of John Ringling, 1936, SN 144 Little documentation exists regarding the career of Niccolò de Simone. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Culturele ondernemers in de Gouden Eeuw: De artistieke en sociaal- economische strategieën van Jacob Backer, Govert Flinck, Ferdinand Bol en Joachim von Sandrart Kok, E.E. Publication date 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kok, E. E. (2013). Culturele ondernemers in de Gouden Eeuw: De artistieke en sociaal- economische strategieën van Jacob Backer, Govert Flinck, Ferdinand Bol en Joachim von Sandrart. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:03 Oct 2021 Summary Jacob Backer (1608/9-1651), Govert Flinck (1615-1660), Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680), and Joachim von Sandrart (1606-1688) belong among the most successful portrait and history painters of the Golden Age in Amsterdam. -

Webfile121848.Pdf

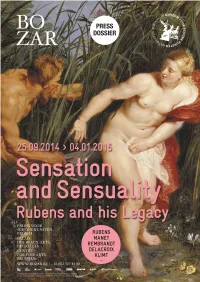

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

Honthorst, Gerrit Van Also Known As Honthorst, Gerard Van Gherardo Della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Honthorst, Gerrit van Also known as Honthorst, Gerard van Gherardo della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656 BIOGRAPHY Gerrit van Honthorst was born in Utrecht in 1592 to a large Catholic family. His father, Herman van Honthorst, was a tapestry designer and a founding member of the Utrecht Guild of St. Luke in 1611. After training with the Utrecht painter Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), Honthorst traveled to Rome, where he is first documented in 1616.[1] Honthorst’s trip to Rome had an indelible impact on his painting style. In particular, Honthorst looked to the radical stylistic and thematic innovations of Caravaggio (Roman, 1571 - 1610), adopting the Italian painter’s realism, dramatic chiaroscuro lighting, bold colors, and cropped compositions. Honthorst’s distinctive nocturnal settings and artificial lighting effects attracted commissions from prominent patrons such as Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1577–1633), Cosimo II, the Grand Duke of Tuscany (1590–1621), and the Marcheses Benedetto and Vincenzo Giustiniani (1554–1621 and 1564–1637). He lived for a time in the Palazzo Giustiniani in Rome, where he would have seen paintings by Caravaggio, and works by Annibale Carracci (Bolognese, 1560 - 1609) and Domenichino (1581–-1641), artists whose classicizing tendencies would also inform Honthorst’s style. The contemporary Italian art critic Giulio Mancini noted that Honthorst was able to command high prices for his striking paintings, which decorated -

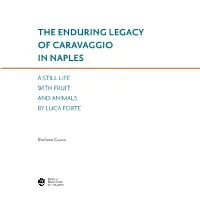

The Enduring Legacy of Caravaggio in Naples

THE ENDURING LEGACY OF CARAVAGGIO IN NAPLES A STILL LIFE WITH FRUIT AND ANIMALS BY LUCA FORTE Stefano Causa ENRICO FRASCIONE ANTIQUARIO [2] [3] LUCA FORTE (Naples, c. 1605 - c. 1660) STILL LIFE WITH FRUIT, A JAY, A KESTREL, A BUTTERFLY, AND A SNAIL Oil on canvas, 41¾ x 71 in (106 x 180.5 cm), c. 1640 [5] its consistency. In the grand productions of the still life masters of the later seventeenth century, there’s a close interaction – not always deferential, and often evenly- THE ENDURING LEGACY OF matched – with the thunderous, far-reaching approach CARAVAGGIO IN NAPLES of a painter such as Luca Giordano (1634-1705). Here, instead, things seem much more clearly-defined – as if the painting were revealing greater composure and A STILL LIFE WITH FRUIT AND following an older pace. The singular quality of such a work – that is, how challenging it is – does not lie in ANIMALS BY LUCA FORTE whether it can be judged according to a criterion of naturalism, but then it cannot be measured against a fully Baroque yardstick, either. It is no longer a question of looking (solely) at the venerated examples left by Caravaggio, Battistello and Ribera, in that precise order; but nor has Giordano emerged on the horizon. So it was that as Enrico and I examined every detail of this rich, kaleidoscopic greengrocer’s stall, I thought of words written by the still life expert Raffaello Causa, which I wanted to use as a subtitle for this essay: “What is characteristic of Luca Forte is a stony, polished A STONY, POLISHED PIGMENT pigment, almost as if – within the formal circumstances “A Neapolitan picture, painted around 1640. -

Faq20200908.Pdf

PREGUNTAS MÁS FRECUENTES Índice 1. Preguntas más frecuentes referentes a HORARIO .................................................................... 3 1.1. ¿Cuál es el horario de apertura del Museo? ....................................................................... 3 1.2. ¿Hay horario de gratuidad? ............................................................................................... 3 1.3. ¿Cuál es el horario de taquilla? .......................................................................................... 3 1.4. ¿Cuál es el horario de la tienda? ........................................................................................ 3 1.5. ¿Cuál es el horario del Café Prado? ................................................................................... 3 2. Preguntas más frecuentes referentes a ENTRADAS y PRECIOS .............................................. 3 2.1. ¿Dónde se pueden adquirir las entradas al Museo? ........................................................... 3 2.2. ¿Cuál es el precio de las entradas? ..................................................................................... 4 2.3. ¿Dónde se recoge el ejemplar incluido en la entrada general + La Guía del Prado? ........... 4 2.4. ¿Qué entradas son válidas durante este periodo? ............................................................... 4 2.5. ¿Dónde pueden comprar sus entradas las personas con discapacidad? ............................. 4 2.6. ¿Dónde se realiza el canje de la Tarjeta anual de Museos Estatales y del ICOM? ............. -

Title the Hands of Rubens: on Copies and Their Reception Author(S)

Title The Hands of Rubens: On Copies and Their Reception Author(s) Büttner, Nils Citation Kyoto Studies in Art History (2017), 2: 41-53 Issue Date 2017-04 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/229459 © Graduate School of Letters, Kyoto University and the Right authors Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 41 The Hands of Rubens: On Copies and Their Reception Nils Büttner Peter Paul Rubens had more than two hands. How else could he have created the enormous number of works still associated with his name? A survey of the existing paintings shows that almost all of his famous paintings exist in more than one version. It is notable that the copies of most of his paintings are very often contemporary, sometimes from his workshop. It is astounding even to see the enormous range of painterly qualities which they exhibit. The countless copies and replicas of his works contributed to increasing Rubens’s fame and immortalizing his name. Not all paintings connected to his name, however, were well suited to do the inventor of the compositions any credit. This resulted in a problem of productions “harmed his reputation (fit du tort à sa reputation).” 1 Joachim von Sandrart, a which already one of his first biographers, Roger de Piles, was aware: some of these 2 “Through his industriousness the City of Antwerpbiographer became who had an exceptional met Rubens art in schoolperson, in on which the other students hand, achieved saw the notable benefits perfection.” of copying3 Rubens’sAccordingly, style for gainingthe art production one of the inapprenticeships Antwerp: in Rubens’s workshop was in great demand. -

January 21, 2020 CAPTIVATING STORIES EMOTIONALLY

For Immediate Release: January 21, 2020 CAPTIVATING STORIES EMOTIONALLY DEPICTED BY SOME OF THE GREATEST RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE PAINTERS, ON VIEW AT THE KIMBELL ART MUSEUM Flesh and Blood: Italian Masterpieces from the Capodimonte Museum March 1–June 14, 2020 FORT WORTH, TX (January 21, 2020) –The Kimbell Art Museum presents the breathtaking special exhibition Flesh and Blood, featuring 40 masterpieces from the Capodimonte Museum in Naples, one of the most important art collections in Italy. This monumental gathering of paintings is a journey through the major artistic achievements of Italian Renaissance and Baroque painting—featuring captivating stories, from Christian martyrdom to mythological passion, and diverse formats and purposes, from the intimacy of private devotion to the grandeur of state portraiture. The works in Flesh and Blood are by some of the greatest artists of the 16th and 17th centuries, including Titian, Raphael, Parmigianino, El Greco, Annibale Carracci, Artemisia Gentileschi, Guido Reni, Jusepe de Ribera and Luca Giordano. Their masterful paintings can be imposing or intimate, violent or tender, extravagant or humble, tragic or even seductive. The exhibition is on view at the Kimbell Art Museum from March 1 through June 14, 2020. “The Museo di Capodimonte in Naples is one of the largest and most spectacular collections in Italy,” commented Eric M. Lee, “and its holdings have a particular strength in paintings of the Renaissance and Baroque periods. These paintings embody innovation, exuberance and grandeur—the result of revolutionary painting techniques and dramatic use of light and dark. The works continue to influence artists and inspire art lovers the world over. -

The Amsterdam Civic Guard Pieces Within and Outside the New Rijksmuseum Pt. IV

Volume 6, Issue 2 (Summer 2014) The Amsterdam Civic Guard Pieces within and Outside the New Rijksmuseum Pt. IV D. C. Meijer Jr., trans. Tom van der Molen Recommended Citation: D. C. Meijer Jr., “The Amsterdam Civic Guard Pieces Within and Outside the New Rijksmuseum Pt. IV,” trans. Tom van der Molen, JHNA 6:2 (Summer 2014) DOI:10.5092/jhna.2014.6.2.4 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/amsterdam-civic-guard-pieces-within-outside-new-rijksmu- seum-part-iv/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This is a revised PDF that may contain different page numbers from the previous version. Use electronic searching to locate passages. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 6:2 (Summer 2014) 1 THE AMSTERDAM CIVIC GUARD PIECES WITHIN AND OUTSIDE THE NEW RIJKSMUSEUM PT. IV D. C. Meijer Jr. (Tom van der Molen, translator) This fourth installment of D. C. Meijer Jr.’s article on Amsterdam civic guard portraits focuses on works by Thomas de Keyser and Joachim von Sandrart (Oud Holland 6 [1888]: 225–40). Meijer’s article was originally published in five in- stallments in the first few issues of the journal Oud Holland. For translations (also by Tom van der Molen) of the first two installments, see JHNA 5, no. 1 (Winter 2013). For the third installment, see JHNA 6, no. -

Between Academic Art and Guild Traditions 21

19 JULIA STROBL, INGEBORG SCHEMPER-SPARHOLZ, quently accompanied Philipp Jakob to Graz in 1733.2 MATEJ KLEMENČIČ The half-brothers Johann Georg Straub (1721–73) and Franz Anton (1726–74/6) were nearly a decade younger. There is evidence that in 1751 Johann Georg assisted at BETWEEN ACADEMIC ART AND Philipp Jakobs’s workshop in Graz before he married in Bad Radkersburg in 1753.3 His sculptural œuvre is GUILD TRADITIONS hardly traceable, and only the figures on the right-side altar in the Church of Our Lady in Bad Radkersburg (ca. 1755) are usually attributed to him.4 The second half- brother, Franz Anton, stayed in Zagreb in the 1760s and early 1770s; none of his sculptural output has been confirmed by archival sources so far. Due to stylistic similarities with his brother’s works, Doris Baričević attributed a number of anonymous sculptures from the 1760s to him, among them the high altar in Ludina The family of sculptors Johann Baptist, Philipp Jakob, and the pulpit in Kutina.5 Joseph, Franz Anton, and Johann Georg Straub, who worked in the eighteenth century on the territory of present-day Germany (Bavaria), Austria, Slovenia, Cro- STATE OF RESEARCH atia, and Hungary, derives from Wiesensteig, a small Bavarian enclave in the Swabian Alps in Württemberg. Due to his prominent position, Johann Baptist Straub’s Johann Ulrich Straub (1645–1706), the grandfather of successful career in Munich awoke more scholarly in- the brothers, was a carpenter, as was their father Jo- terest compared to his younger brothers, starting with hann Georg Sr (1674–1755) who additionally acted as his contemporary Johann Caspar von Lippert.