DIRECTIONS to BAROQUE NAPLES Helen Hills

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rough Guide to Naples & the Amalfi Coast

HEK=> =K?:;I J>;HEK=>=K?:;je CVeaZh i]Z6bVaÒ8dVhi D7FB;IJ>;7C7B<?9E7IJ 7ZcZkZcid BdcYgV\dcZ 8{ejV HVc<^dg\^d 8VhZgiV HVciÉ6\ViV YZaHVcc^d YZ^<di^ HVciVBVg^V 8{ejVKiZgZ 8VhiZaKdaijgcd 8VhVaY^ Eg^cX^eZ 6g^Zcod / AV\dY^EVig^V BVg^\a^Vcd 6kZaa^cd 9WfeZ_Y^_de CdaV 8jbV CVeaZh AV\dY^;jhVgd Edoojda^ BiKZhjk^jh BZgXVidHVcHZkZg^cd EgX^YV :gXdaVcd Fecf[__ >hX]^V EdbeZ^ >hX]^V IdggZ6ccjco^ViV 8VhiZaaVbbVgZY^HiVW^V 7Vnd[CVeaZh GVkZaad HdggZcid Edh^iVcd HVaZgcd 6bVa[^ 8{eg^ <ja[d[HVaZgcd 6cVX{eg^ 8{eg^ CVeaZh I]Z8Vbe^;aZ\gZ^ Hdji]d[CVeaZh I]Z6bVa[^8dVhi I]Z^haVcYh LN Cdgi]d[CVeaZh FW[ijkc About this book Rough Guides are designed to be good to read and easy to use. The book is divided into the following sections, and you should be able to find whatever you need in one of them. The introductory colour section is designed to give you a feel for Naples and the Amalfi Coast, suggesting when to go and what not to miss, and includes a full list of contents. Then comes basics, for pre-departure information and other practicalities. The guide chapters cover the region in depth, each starting with a highlights panel, introduction and a map to help you plan your route. Contexts fills you in on history, books and film while individual colour sections introduce Neapolitan cuisine and performance. Language gives you an extensive menu reader and enough Italian to get by. 9 781843 537144 ISBN 978-1-84353-714-4 The book concludes with all the small print, including details of how to send in updates and corrections, and a comprehensive index. -

Baroque and Rococo Art and Architecture 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BAROQUE AND ROCOCO ART AND ARCHITECTURE 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robert Neuman | 9780205951208 | | | | | Baroque and Rococo Art and Architecture 1st edition PDF Book Millon Published by George Braziller, Inc. He completed two chapters and a table of con- tents for a projected five-volume treatise on painting, Discorso intorno alle immagini sacre e profane, published in part in , which, although directed at a Bolognese audience, had a great impact on artistic practice throughout the Italian peninsula. As Rubenists they painted in a similar manner; indeed contempo- raries called both "the Van Dyck of France" because they borrowed so considerably from Flemish Baroque pictorial tradition. United Kingdom. Francis ca. Both authors portray the sim- artists to study its sensuous and emot1onal ly stimulating effects. Create a Want BookSleuth Can't remember the title or the author of a book? Photographs by Wim Swaan. Henry A. Championing the that he took liberties with generally accepted ideas concept of art as the Bible of the illiterate, and pressing for regarding the Day of Judgment. Dust Jacket Condition: None. The university also prompted a strong antiquarian tradition among collectors, who sought out ancient sculpture and encouraged historical subjects in painting. Published by George Braziller To browse Academia. Thus Louis XIV, worshiping from the balcony, ruler or noble and focused on status rather than personal- appeared as successor to the great rulers of the past, spe- ity. Millon, Vincent Scully Jr. Gently used, light corner wear; crease to the spine. Sean B. The author, former Director of the Courtauld Institute of Art, is known internationally for his many works on French and Italian architecture and painting. -

Geomorphological Evolution of Phlegrean Volcanic Islands Near Naples, Southern Italy1

Berlin .Stuttgart Geomorphological evolution of Phlegrean volcanic islands near Naples, southern Italy1 by G.AIELLO, D.BARRA, T.DE PIPPO, C.DONADIO, and C.PETROSINO with 9 figures and 5 tables Summary. Using volcanological, morphological, palaeoecological and geoarchaeological data we reconstructed the complex evolution of the island volcanic system of Procida-Vivara, situated west of Naples betweenthe lsland of lschia and the PhlegreanFields, far the last 75 ky. Late Pleistocenemorphological evolution was chiefly controlled by a seriesof pyroclas tic eruptions that resulted in at least eight volcanic edifices, mainly under water. Probably the eruptive centresshifted progressively clockwise until about 18 ky BP when volcanic develop ment on the islands ceased. The presenceof stretches of marine terraces and traces of wave cut notches, both be low and abovè'current sea levels, the finding of exposed infralittoral rnicrofossils, and the identification of three palaeo-surfacesburied by palaeosoilsindicates at least three differen tial uplift phases.These phases interacted with postglacial eustaticfIuctuations, and were sep arated by at least two periods of generai stability in vertical movements. A final phase of ground stability, characterisedby the deposition of Phlegrean and lschia pyroclastics, start ed in the middle Holocene. Finally, fIattened surfacesand a sandy tombolo developedup to the present-day. Recent archaeological surveys and soil-borings at Procida confirm the presence of a lagoon followed by marshland at the back of a sandy tombolo that were formed after the last uplift between the Graeco-Roman periodandthe15di_16dicentury. These areaswere gradu ally filled with marine and continental sedimentsup to the 20di century. ' Finally, our investigation showed that the volcanic sector of Procida-Vivara in the late Pleistocene-Holocenewas affected by vertical displacementswhich were independent of and less marked than the concurrent movement in the adjacent sectors of lschia and of the Phle grean Fields. -

The Symbolism of Blood in Two Masterpieces of the Early Italian Baroque Art

The Symbolism of blood in two masterpieces of the early Italian Baroque art Angelo Lo Conte Throughout history, blood has been associated with countless meanings, encompassing life and death, power and pride, love and hate, fear and sacrifice. In the early Baroque, thanks to the realistic mi of Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi, blood was transformed into a new medium, whose powerful symbolism demolished the conformed traditions of Mannerism, leading art into a new expressive era. Bearer of macabre premonitions, blood is the exclamation mark in two of the most outstanding masterpieces of the early Italian Seicento: Caravaggio's Beheading a/the Baptist (1608)' (fig. 1) and Artemisia Gentileschi's Judith beheading Halo/ernes (1611-12)2 (fig. 2), in which two emblematic events of the Christian tradition are interpreted as a representation of personal memories and fears, generating a powerful spiral of emotions which constantly swirls between fiction and reality. Through this paper I propose that both Caravaggio and Aliemisia adopted blood as a symbolic representation of their own life-stories, understanding it as a vehicle to express intense emotions of fear and revenge. Seen under this perspective, the red fluid results as a powerful and dramatic weapon used to shock the viewer and, at the same time, express an intimate and anguished condition of pain. This so-called Caravaggio, The Beheading of the Baptist, 1608, Co-Cathedral of Saint John, Oratory of Saint John, Valletta, Malta. 2 Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith beheading Halafernes, 1612-13, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples. llO Angelo La Conte 'terrible naturalism'3 symbolically demarks the transition from late Mannerism to early Baroque, introducing art to a new era in which emotions and illusion prevail on rigid and controlled representation. -

Spectral Clustering on Mercury Hollows: the Dominici Crater Case

Lunar and Planetary Science XLVIII (2017) 1329.pdf SPECTRAL CLUSTERING ON MERCURY HOLLOWS: THE DOMINICI CRATER CASE. A. Lucchetti1, M. Pajola2,3,1, G. Cremonese1, C. Carli4, G. A. Marzo5 and T. Roush3, 1INAF-Astronomical Observatory of Padova, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, 35131 Padova, Italy ([email protected] ), 2Universities Space Research Association, NASA NPP Program (Supported by an appointment at NASA Ames Research Center: [email protected]), 3NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA; 4INAF-IAPS Roma, Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali di Roma, Via del Fosso del Cavaliere, 00133 Rome, Italy; 5ENEA Centro Ricerche Casaccia, 00123 Rome, Italy. Introduction: The Mercury Dual Imaging System [8], i.e. incidence angle of 30°, emission angle of 0° (MDIS, [1]) onboard NASA MESSENGER (MErcury and phase angle of 30°. On the photometrically cor- Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and rected dataset we applied a statistical clustering over Ranging) spacecraft, provided the first global coverage the entire dataset based on a K-means partitioning al- of Mercury's surface with varying spatial resolution. gorithm [9]. It was developed and evaluated by [9-11] Early in the mission, high-resolution images showed and makes use of the Calinski and Harabasz criterion that specific areas exhibiting high reflectance and rela- [12] to find the intrinsically natural number of clusters, tive bluer in color were composed of shallow, irregular making the process unsupervised. A natural number of and rimless, flat-floored depressions with bright interi- ten clusters was identified within the crater and its ors and halos, often found on crater walls, rims, floors closest surroundings, see Fig. -

Mattia & Marianovella Romano

Mattia & MariaNovella Romano A Selection of Master Drawings A Selection of Master Drawings Mattia & Maria Novella Romano A Selection of Drawings are sold mounted but not framed. Master Drawings © Copyright Mattia & Maria Novelaa Romano, 2015 Designed by Mattia & Maria Novella Romano and Saverio Fontini 2015 Mattia & Maria Novella Romano 36, Borgo Ognissanti 50123 Florence – Italy Telephone +39 055 239 60 06 Email: [email protected] www.antiksimoneromanoefigli.com Mattia & Maria Novella Romano A Selection of Master Drawings 2015 F R FRATELLI ROMANO 36, Borgo Ognissanti Florence - Italy Acknowledgements Index of Artists We would like to thank Luisa Berretti, Carlo Falciani, Catherine Gouguel, Martin Hirschoeck, Ellida Minelli, Cristiana Romalli, Annalisa Scarpa and Julien Stock for their help in the preparation of this catalogue. Index of Artists 15 1 3 BARGHEER EDUARD BERTANI GIOVAN BAttISTA BRIZIO FRANCESCO (?) 5 9 7 8 CANTARINI SIMONE CONCA SEBASTIANO DE FERRARI GREGORIO DE MAttEIS PAOLO 12 10 14 6 FISCHEttI FEDELE FONTEBASSO FRANCESCO GEMITO VINCENZO GIORDANO LUCA 2 11 13 4 MARCHEttI MARCO MENESCARDI GIUSTINO SABATELLI LUIGI TASSI AGOSTINO 1. GIOVAN BAttISTA BERTANI Mantua c. 1516 – 1576 Bacchus and Erigone Pen, ink and watercoloured ink on watermarked laid paper squared in chalk 208 x 163 mm. (8 ¼ x 6 ⅜ in.) PROVENANCE Private collection. Giovan Battista Bertani was the successor to Giulio At the centre of the composition a man with long hair Romano in the prestigious work site of the Ducal Palace seems to be holding a woman close to him. She is seen in Mantua.1 His name is first mentioned in documents of from behind, with vines clinging to her; to the sides of 1531 as ‘pictor’, under the direction of the master, during the central group, there are two pairs of little erotes who the construction works of the “Palazzina della Paleologa”, play among themselves, passing bunches of grapes to each which no longer exists, in the Ducal Palace.2 According other. -

INU - SIU Sulla “Riforma Della Disciplina Urbanistica” Schedatura Dei Sistemi Di Governo Del Territorio Delle Regioni Italiane

Commissione CeNSU - INU - SIU sulla “Riforma della Disciplina Urbanistica” Schedatura dei sistemi di governo del territorio delle regioni italiane Elaborazione della scheda a cura di: Gerardo Carpentieri, Carmela Gargiulo, Rosa Anna La Rocca e Alessandro Sgobbo 1. Regione: CAMPANIA 2. Legge urbanistica vigente: Legge Regionale 22 dicembre 2004, n. 16 Norme sul Governo del territorio e sm. http://www.sito.regione.campania.it/territorio/documenti/dl_urbanistica03.pdf REGOLAMENTO DI ATTUAZIONE N. 5/2011 http://www.sito.regione.campania.it/regolamenti/regolamento05_2011.pdf È in stato avanzato di elaborazione una nuova Legge Regionale sul governo del territorio il cui iter si è rallentato a causa dell’evento pandemico Covid-19. 3. Dati di base del territorio regionale. complessiva 13.670,95 kmq Superficie Circa 950 kmq (ISPRA e (kmq) urbanizzata PTR)1 1991 5.631.659 ab. Popolazione 2001 5.701.931 ab. (ab) 2011 5.766.810 ab. 2020 5.785.861 ab Suolo consumato 2019 140.033 ha (ha) Fonte: Dati Istat – Dati ISPRA 2019 Suddivisione amministrativa 4. Dati relativi alla suddivisione amministrativa della Regione (al 2020). Province o altre unità Città Comuni subregionali Metropolitane Numero complessivo 4 1 550 Superficie 1.178,93 kmq Popolazione 3.082.905 ab. Eventuali suddivisioni in zone 5 aree omogenee omogenee proposte2 1 Nucleo Di Valutazione E Verifica Degli Investimenti Pubblici Regione Campania (2010) Analisi di Contesto Territoriale della Regione Campania http://regione.campania.it/assets/documents/nvvip-analisi-del-contesto-territoriale-regionale-a-cura-del- nvvip-ottobre-2010.pdf 2 Si fa riferimento alla “Proposta orientativa di identificazione delle Zone Omogenee della Città Metropolitana di Napoli ai sensi della Legge 56/2014 e dello Statuto Metropolitano” approvata con Deliberazione Sindacale DLG-49-2019 del 13/02/2019 visionabile a: https://www.cittametropolitana.na.it/documents/10181/3486979/proposta%20zone%20omogenee.pdf/9c5a72ae- f48e-480b-86cb-079225c54166 [accesso del 5 dicembre 2020]. -

Ribera's Drunken Silenusand Saint Jerome

99 NAPLES IN FLESH AND BONES: RIBERA’S DRUNKEN SILENUS AND SAINT JEROME Edward Payne Abstract Jusepe de Ribera did not begin to sign his paintings consistently until 1626, the year in which he executed two monumental works: the Drunken Silenus and Saint Jerome and the Angel of Judgement (Museo di Capodimonte, Naples). Both paintings include elaborate Latin inscriptions stating that they were executed in Naples, the city in which the artist had resided for the past decade and where he ultimately remained for the rest of his life. Taking each in turn, this essay explores the nature and implications of these inscriptions, and offers new interpretations of the paintings. I argue that these complex representations of mythological and religious subjects – that were destined, respectively, for a private collection and a Neapolitan church – may be read as incarnations of the city of Naples. Naming the paintings’ place of production and the artist’s city of residence in the signature formulae was thus not coincidental or marginal, but rather indicative of Ribera inscribing himself textually, pictorially and corporeally in the fabric of the city. Keywords: allegory, inscription, Naples, realism, Jusepe de Ribera, Saint Jerome, satire, senses, Silenus Full text: http://openartsjournal.org/issue-6/article-5 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5456/issn.2050-3679/2018w05 Biographical note Edward Payne is Head Curator of Spanish Art at The Auckland Project and an Honorary Fellow at Durham University. He previously served as the inaugural Meadows/Mellon/Prado Curatorial Fellow at the Meadows Museum (2014–16) and as the Moore Curatorial Fellow in Drawings and Prints at the Morgan Library & Museum (2012–14). -

The Collecting, Dealing and Patronage Practices of Gaspare Roomer

ART AND BUSINESS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NAPLES: THE COLLECTING, DEALING AND PATRONAGE PRACTICES OF GASPARE ROOMER by Chantelle Lepine-Cercone A thesis submitted to the Department of Art History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (November, 2014) Copyright ©Chantelle Lepine-Cercone, 2014 Abstract This thesis examines the cultural influence of the seventeenth-century Flemish merchant Gaspare Roomer, who lived in Naples from 1616 until 1674. Specifically, it explores his art dealing, collecting and patronage activities, which exerted a notable influence on Neapolitan society. Using bank documents, letters, artist biographies and guidebooks, Roomer’s practices as an art dealer are studied and his importance as a major figure in the artistic exchange between Northern and Sourthern Europe is elucidated. His collection is primarily reconstructed using inventories, wills and artist biographies. Through this examination, Roomer emerges as one of Naples’ most prominent collectors of landscapes, still lifes and battle scenes, in addition to being a sophisticated collector of history paintings. The merchant’s relationship to the Spanish viceregal government of Naples is also discussed, as are his contributions to charity. Giving paintings to notable individuals and large donations to religious institutions were another way in which Roomer exacted influence. This study of Roomer’s cultural importance is comprehensive, exploring both Northern and Southern European sources. Through extensive use of primary source material, the full extent of Roomer’s art dealing, collecting and patronage practices are thoroughly examined. ii Acknowledgements I am deeply thankful to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Sebastian Schütze. -

Declaration in Support of Plaintiffs

Case: 18-36082, 02/07/2019, ID: 11183380, DktEntry: 21-12, Page 1 of 80 Case No. 18-36082 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT KELSEY CASCADIA ROSE JULIANA, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al., Defendants-Appellants. On Interlocutory Appeal Pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b) DECLARATION OF STEVEN W. RUNNING IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’ URGENT MOTION UNDER CIRCUIT RULE 27-3(b) FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION JULIA A. OLSON PHILIP L. GREGORY (OSB No. 062230, CSB No. 192642) (CSB No. 95217) Wild Earth Advocates Gregory Law Group 1216 Lincoln Street 1250 Godetia Drive Eugene, OR 97401 Redwood City, CA 94062 Tel: (415) 786-4825 Tel: (650) 278-2957 ANDREA K. RODGERS (OSB No. 041029) Law Offices of Andrea K. Rodgers 3026 NW Esplanade Seattle, WA 98117 Tel: (206) 696-2851 Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees Case: 18-36082, 02/07/2019, ID: 11183380, DktEntry: 21-12, Page 2 of 80 I, Steven W. Running, hereby declare and if called upon would testify as follows: 1. In this Declaration, I offer my expert opinion about how excessive greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, largely from the burning of fossil fuels, are causing climate change that is dangerously warming the surface of the Earth and causing devastating impacts to the Youth Plaintiffs in this case. Because there is a decades-long delay between the release of carbon dioxide (CO2) and the resultant warming of the climate, these Youth Plaintiffs have not yet experienced the full amount of warming that will occur from emissions already released. -

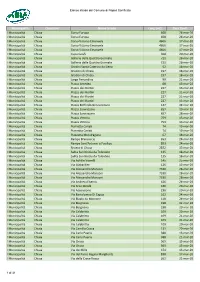

Municipalità Quartiere Nome Strada Lung.(Mt) Data Sanif

Elenco strade del Comune di Napoli Sanificate Municipalità Quartiere Nome Strada Lung.(mt) Data Sanif. I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Europa 608 24-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Europa 608 24-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Cupa Caiafa 368 20-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Galleria delle Quattro Giornate 721 28-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Galleria delle Quattro Giornate 721 28-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradini Santa Caterina da Siena 52 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradoni di Chiaia 197 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradoni di Chiaia 197 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Largo Ferrandina 99 21-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Amedeo 68 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 21-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 21-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Roffredo Beneventano 147 24-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Sannazzaro 657 20-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Sannazzaro 657 28-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Vittoria 759 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Vittoria 759 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Cariati 74 19-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Cariati 74 19-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Mondragone 67 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Rampe Brancaccio 653 24-mar-20 I Municipalità -

De Gasperi Sede Di Castellammare Di Stabia

Allegato 8 Competenza territoriale delle Sedi di riferimento SEDE DI NAPOLI (continua Sede di Napoli) 80021 AFRAGOLA 80046 SAN GIORGIO A CREMANO 80071 ANACAPRI 80040 SAN SEBASTIANO AL VESUVIO 80022 ARZANO 80029 SANT'ANTIMO 80070 BACOLI 80070 SERRARA FONTANA 80070 BARANO D'ISCHIA 80023 CAIVANO NAPOLI - DE GASPERI 80073 CAPRI 80012 CALVIZZANO 80024 CARDITO 80014 GIUGLIANO IN CAMPANIA 80074 CASAMICCIOLA TERME 80016 MARANO DI NAPOLI 80025 CASANDRINO 80017 MELITO DI NAPOLI 80020 CASAVATORE 80018 MUGNANO DI NAPOLI 80026 CASORIA 80127 NAPOLI 80020 CRISPANO 80128 NAPOLI 80056 ERCOLANO 80131 NAPOLI 80075 FORIO 80136 NAPOLI 80027 FRATTAMAGGIORE 80144 NAPOLI 80020 FRATTAMINORE 80145 NAPOLI 80028 GRUMO NEVANO 80019 QUALIANO 80077 ISCHIA 80010 VILLARICCA 80076 LACCO AMENO 80070 MONTE DI PROCIDA SEDE DI CASTELLAMMARE DI STABIA 80121 NAPOLI 80122 NAPOLI 80051 AGEROLA 80123 NAPOLI 80041 BOSCOREALE 80124 NAPOLI 80042 BOSCOTRECASE 80125 NAPOLI 80050 CASOLA DI NAPOLI 80126 NAPOLI 80053 CASTELLAMMARE DI STABIA 80129 NAPOLI 80054 GRAGNANO 80132 NAPOLI 80050 LETTERE 80133 NAPOLI 80061 MASSA LUBRENSE 80134 NAPOLI 80062 META 80135 NAPOLI 80063 PIANO DI SORRENTO 80137 NAPOLI 80050 PIMONTE 80138 NAPOLI 80040 POGGIOMARINO 80139 NAPOLI 80045 POMPEI 80141 NAPOLI 80065 SANT'AGNELLO 80142 NAPOLI 80057 SANT'ANTONIO ABATE 80143 NAPOLI 80050 SANTA MARIA LA CARITA' 80146 NAPOLI 80067 SORRENTO 80147 NAPOLI 80040 STRIANO 80044 OTTAVIANO 80058 TORRE ANNUNZIATA 80055 PORTICI 80059 TORRE DEL GRECO 80078 POZZUOLI 80040 TRECASE 80079 PROCIDA 80069 VICO EQUENSE 80010 QUARTO (continua