Printed in Munchen, 1925), 195–96

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

During the Seventeenth Century, Dutch Portraits Were Actively Commissioned by Corporate Groups and by Individuals from a Range of Economic and Social Classes

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-69803-1 - Public Faces and Private Identities in Seventeenth-Century Holland: Portraiture and the Production of Community Ann Jensen Adams Frontmatter More information PUBLIC FACES AND PRIVATE IDENTITIES IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY HOLLAND During the seventeenth century, Dutch portraits were actively commissioned by corporate groups and by individuals from a range of economic and social classes. They became among the most important genres of painting. Not merely mimetic representations of their subjects, many of these works create a new dialogic rela- tionship with the viewer. In this study, Ann Jensen Adams examines four portrait genres – individuals, family, history portraits, and civic guards. She analyzes these works in relation to inherited visual traditions; contemporary art theory; chang- ing cultural beliefs about the body, sight, and the image itself; and current events. Adams argues that as individuals became unmoored from traditional sources of identity, such as familial lineage, birthplace, and social class, portraits helped them to find security in a self-aware subjectivity and the new social structures that made possible the “economic miracle” that has come to be known as the Dutch Golden Age. Ann Jensen Adams is associate professor of art history at the University of California, Santa Barbara. A scholar of Dutch painting, she curated the exhibi- tion Dutch Paintings from New York Private Collections (1988) and edited Rembrandt’s “Bathsheba Reading David’s Letter” (1998). She has contributed essays to numer- ous exhibition catalogues and essay collections including Leselust. Niederl¨andische Malerei von Rembrandt bis Vermeer (1993), Landscape and Power (1994), Looking at Seventeenth-Century Dutch Painting: Realism Reconsidered (1997), Renaissance Culture and the Everyday (1999), and Love Letters: A Theme in Dutch Seventeenth-Century Genre Painting (2003) and published articles in The Art Bulletin and the Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek. -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

EEN BRIEF VAN THOMAS DE KEYSER, DOOR A. W. WEISSMAN. NDER De Papieren Van Den Beeldhouwer NICHOLAS STONE, Den Schoonzoon Van

EEN BRIEF VAN THOMAS DE KEYSER, DOOR A. W. WEISSMAN. NDER de papieren van den beeldhouwer NICHOLAS STONE, den schoonzoon van HENDRIK DE KEYSER, die in Sir JOHN SOANE's Museum te Londen bewaard worden, bevindt zich ook een brief van THOMAS DE KEYSER, waarvan ik door de welwillendheid van den directeur, de heer WALTER L. SPIERS, een afschrift mocht maken. De brief luidt als volgt. "Eerwaerde en seer discrete broeder en zuster STONE, na onse vriendelycke groetenisse ende wensinge alles goedts, soo sal U. L, door dezen verstaen ons aller gesontheyt; de uwen sijn wij van herte wensende. Hebben U. L, brieven als oock den beverhoet wel ontfangen, staet mij heel wel aen, bedancke U. L, voor de moeyte. Hebt mij maer te comman- deren in U. L. dienst en zal na mijn vermoghen niet manqueren. ?VAN SOMEREN heeft twe mael 2 £ betaelt, hebbe U. L. voor deze twe pont in rekeningh gebracht, alst U. L. belieft pertinente notitie daervan uyt mijn boeck te hebben zal het U. L. senden ofte de saeck is soo. 62 "Int jaer 1637, daer U. L. mij het laken sont resteerde mijn van U. L. f 54 - I I - 0 het laken dat U. L, sont f 6 r - o - o de papegaye kouwe ... " I 5 - o - o van VAN SOMEREN... " 22 - O - 0 aan SALOMON oom be- - - van VAN SOMEREN... " 22 4 8 taelt.............. " 20 - 0 - 0 - - de bever 27 14 0 2 lijsten aen U.L. zoone " I –10 – o de doos gespen ...... " 6 - o de kaggel met oncosten " 36 - 3 - 8 f I33- 4.-8 f 1 27 - 4 - 8 zoodat U. -

Keyser, Thomas De Dutch, 1596 - 1667

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Keyser, Thomas de Dutch, 1596 - 1667 BIOGRAPHY Thomas de Keyser was the second son of Hendrick de Keyser (1565–1621), the famed Dutch architect, sculptor, and municipal stonemason of the city of Amsterdam, and his wife Beyken (Barbara) van Wildere, who hailed from Antwerp.[1] The family lived in a house that was part of the municipal stone yard along the Amstel River, between the Kloveniersburgwal and the Groenburgwal.[2] Thomas and his brothers Pieter and Willem were trained by their father in architecture, and each also became a highly regarded master stonemason and stone merchant in his own right. On January 10, 1616, the approximately 19-year-old Thomas became one of his father’s apprentices. As he must already have become proficient at the trade while growing up at the Amsterdam stone yard, the formal two-year apprenticeship that followed would have fulfilled the stonemasons’ guild requirements.[3] Thomas, however, achieved his greatest prominence as a painter and became the preeminent portraitist of Amsterdam’s burgeoning merchant class, at least until the arrival of Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606 - 1669) in 1632. Nothing is known about his artistic training as a painter, which likely occurred in his younger years. Four Amsterdam portraitists have been considered his possible teacher. Ann Jensen Adams, in her catalogue raisonné of Thomas de Keyser, posits (based on circumstantial evidence) that Cornelis van der Voort (c. 1576–1624) -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Culturele ondernemers in de Gouden Eeuw: De artistieke en sociaal- economische strategieën van Jacob Backer, Govert Flinck, Ferdinand Bol en Joachim von Sandrart Kok, E.E. Publication date 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kok, E. E. (2013). Culturele ondernemers in de Gouden Eeuw: De artistieke en sociaal- economische strategieën van Jacob Backer, Govert Flinck, Ferdinand Bol en Joachim von Sandrart. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:03 Oct 2021 Summary Jacob Backer (1608/9-1651), Govert Flinck (1615-1660), Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680), and Joachim von Sandrart (1606-1688) belong among the most successful portrait and history painters of the Golden Age in Amsterdam. -

Webfile121848.Pdf

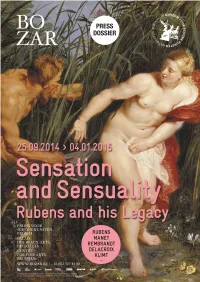

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

Country House in a Park Informal, Almost Wilderness Garden in This Painting Contains Architectural Elements Characteristic of C

different work because the Washington painting was sold by ile, 3rd Baron Savile [b. 1919], Rufford Abbey, Notting the Baron de Beurnonville only in 1881. hamshire; (sale, Christie, Manson & Woods, London, 18 2. The provenance given in Strohmer's 1943 catalogue of November 1938, no. 123); Rupert L. Joseph (d. 1959), New the Liechtenstein Collection and in the 1948 Lucerne exhibi York.1 tion catalogue contains misinformation. 3. See The Hague 1981, 34, and also Kuznetsov 1973, Exhibited: Jacob van Ruisdael, Mauritshuis, The Hague; Fogg 31-41. Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachu 4. Wright 1984, cat. 7. setts, 1981-1982, no. 54. 5. Landscape with a Footbridge (inv. no. 49.1.156) and Land scape with Bridge, Cattle, and Figures (inv. no. 29). DEPICTIONS of elegant country houses came into References vogue in the latter half of the seventeenth century as 1896 Bode: 99. 1903 Suida: 116. increasing numbers of wealthy Dutch merchants 1907- 1927 HdG, 4 (1912): 94, no. 295 129,no.407. built homes along the river Vecht and in other pic 1908 Hoss: 58, I.14, repro. turesque locations in the Netherlands. Artists who 1911 Preyer: 247-248. specialized in architectural painting, among them 1927 Kronfeld: 184-185, no. 911. Jan van der Heyden (q.v.), depicted the houses and 1928 Rosenberg: 87, no. 252. gardens in great detail. Surprisingly, however, not '943 Strohmer: 101, pi. 69. 1948 Lucerne: no. 175. all of these seemingly accurate representations por 1965 NGA: 119, no. 1637. tray actual structures; sometimes the scenes were 1968 NGA: 106, no. 1637. purely imaginary, intended to project an ideal of "975 NGA: 316-317, repro. -

Honthorst, Gerrit Van Also Known As Honthorst, Gerard Van Gherardo Della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Honthorst, Gerrit van Also known as Honthorst, Gerard van Gherardo della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656 BIOGRAPHY Gerrit van Honthorst was born in Utrecht in 1592 to a large Catholic family. His father, Herman van Honthorst, was a tapestry designer and a founding member of the Utrecht Guild of St. Luke in 1611. After training with the Utrecht painter Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), Honthorst traveled to Rome, where he is first documented in 1616.[1] Honthorst’s trip to Rome had an indelible impact on his painting style. In particular, Honthorst looked to the radical stylistic and thematic innovations of Caravaggio (Roman, 1571 - 1610), adopting the Italian painter’s realism, dramatic chiaroscuro lighting, bold colors, and cropped compositions. Honthorst’s distinctive nocturnal settings and artificial lighting effects attracted commissions from prominent patrons such as Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1577–1633), Cosimo II, the Grand Duke of Tuscany (1590–1621), and the Marcheses Benedetto and Vincenzo Giustiniani (1554–1621 and 1564–1637). He lived for a time in the Palazzo Giustiniani in Rome, where he would have seen paintings by Caravaggio, and works by Annibale Carracci (Bolognese, 1560 - 1609) and Domenichino (1581–-1641), artists whose classicizing tendencies would also inform Honthorst’s style. The contemporary Italian art critic Giulio Mancini noted that Honthorst was able to command high prices for his striking paintings, which decorated -

Country House in a Park C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Jacob van Ruisdael Dutch, c. 1628/1629 - 1682 Country House in a Park c. 1675 oil on canvas overall: 76.3 x 97.5 cm (30 1/16 x 38 3/8 in.) framed: 98.4 x 118.4 x 6.7 cm (38 3/4 x 46 5/8 x 2 5/8 in.) Inscription: lower left: J v Ruisdael (JvR in ligature) Gift of Rupert L. Joseph 1960.2.1 ENTRY Depictions of elegant country houses came into vogue in the latter half of the seventeenth century as increasing numbers of wealthy Dutch merchants built homes along the river Vecht and in other picturesque locations in the Netherlands. Artists who specialized in architectural painting, among them Jan van der Heyden (Dutch, 1637 - 1712), depicted the houses and gardens in great detail. Surprisingly, however, not all of these seemingly accurate representations portray actual structures; sometimes the scenes were purely imaginary, intended to project an ideal of country existence rather than its actuality (see Van der Heyden’s An Architectural Fantasy). Ruisdael, who painted views of country houses only rarely during his long career, was not an artist who felt constrained to convey a precise record of an actual site, and it seems probable that this view of a country estate is an imaginative reconstruction of one he had seen. The elegant classicist villa standing beyond the informal, almost wilderness garden in this painting contains architectural elements characteristic of country houses from the period. -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Pendantbildnisse bei Rembrandt von 1631 bis 1634“ Verfasserin Ingeborg Wilfinger angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2008 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 315 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Kunstgeschichte Betreuer: O. Univ. – Prof. Dr. Artur Rosenauer INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1.0 EINLEITUNG………………………………………………………………..……..3 1.1 Zielsetzung…………………………………………………………….….…..…..5 2.0 FORSCHUNGSLAGE ZU REMBRANDTS FRÜHEM PORTRÄTSCHAFFEN………………………………………...……..7 2.1 Alois Riegl: Das holländische Gruppenporträt…………...……………...15 3.0 DAS PORTRÄT IN DEN NÖRDLICHEN NIEDERLANDEN DES SPÄTEN 16. UND FRÜHEN 17. JAHRHUNDERTS…..……………...26 3.1 Exkurs: Das Schützenbild als Beispiel für ein neues Bewusstsein der bürgerlichen Oberschicht Amsterdams………….…..26 3.2 Die Porträtproduktion in Amsterdam von 1580 – 1630……………….…27 4.0 PENDANTPORTRÄTS..…………………………………………………….….30 4.1 Porträtbüsten……………….………………………………………….………..30 4.1.1 Jacques de Gheyn III. (London, The Dulwich Picture Gallery)- Maurits Huygens (Hamburg, Kunsthalle).………………………………………30 4.1.2 Porträt eines 41- jährigen Mannes (Pasadena, Norton Simon Museum of Art) - Porträt einer 40 – jährigen Frau (Louisville, J.B. Speed Art Museum) Dirck Jansz. Pesser (Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Museum of Art) - Haesje Jacobsdr. van Cleyburg (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum)……….………36 4.2 Kniestücke….……………………………………………………………….…..41 4.2.1 Porträt eines sitzenden Mannes (Wien, Kunsthistorisches Museum)- Porträt einer sitzenden Frau (Wien, Kunsthistorisches Museum).…………...41 -

Title the Hands of Rubens: on Copies and Their Reception Author(S)

Title The Hands of Rubens: On Copies and Their Reception Author(s) Büttner, Nils Citation Kyoto Studies in Art History (2017), 2: 41-53 Issue Date 2017-04 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/229459 © Graduate School of Letters, Kyoto University and the Right authors Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 41 The Hands of Rubens: On Copies and Their Reception Nils Büttner Peter Paul Rubens had more than two hands. How else could he have created the enormous number of works still associated with his name? A survey of the existing paintings shows that almost all of his famous paintings exist in more than one version. It is notable that the copies of most of his paintings are very often contemporary, sometimes from his workshop. It is astounding even to see the enormous range of painterly qualities which they exhibit. The countless copies and replicas of his works contributed to increasing Rubens’s fame and immortalizing his name. Not all paintings connected to his name, however, were well suited to do the inventor of the compositions any credit. This resulted in a problem of productions “harmed his reputation (fit du tort à sa reputation).” 1 Joachim von Sandrart, a which already one of his first biographers, Roger de Piles, was aware: some of these 2 “Through his industriousness the City of Antwerpbiographer became who had an exceptional met Rubens art in schoolperson, in on which the other students hand, achieved saw the notable benefits perfection.” of copying3 Rubens’sAccordingly, style for gainingthe art production one of the inapprenticeships Antwerp: in Rubens’s workshop was in great demand. -

The Amsterdam Civic Guard Pieces Within and Outside the New Rijksmuseum Pt. IV

Volume 6, Issue 2 (Summer 2014) The Amsterdam Civic Guard Pieces within and Outside the New Rijksmuseum Pt. IV D. C. Meijer Jr., trans. Tom van der Molen Recommended Citation: D. C. Meijer Jr., “The Amsterdam Civic Guard Pieces Within and Outside the New Rijksmuseum Pt. IV,” trans. Tom van der Molen, JHNA 6:2 (Summer 2014) DOI:10.5092/jhna.2014.6.2.4 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/amsterdam-civic-guard-pieces-within-outside-new-rijksmu- seum-part-iv/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This is a revised PDF that may contain different page numbers from the previous version. Use electronic searching to locate passages. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 6:2 (Summer 2014) 1 THE AMSTERDAM CIVIC GUARD PIECES WITHIN AND OUTSIDE THE NEW RIJKSMUSEUM PT. IV D. C. Meijer Jr. (Tom van der Molen, translator) This fourth installment of D. C. Meijer Jr.’s article on Amsterdam civic guard portraits focuses on works by Thomas de Keyser and Joachim von Sandrart (Oud Holland 6 [1888]: 225–40). Meijer’s article was originally published in five in- stallments in the first few issues of the journal Oud Holland. For translations (also by Tom van der Molen) of the first two installments, see JHNA 5, no. 1 (Winter 2013). For the third installment, see JHNA 6, no.