Typography Day 2014 - Typography and Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perubahan Menu Tertakluk Pada Chef

PERUBAHAN MENU TERTAKLUK PADA CHEF ISNIN ULAM - ULAMAN Daun Kesum , Daun Gajus ,Daun Kadok ¸ Daun Pegaga , Kacang Botoi , Mix Salad , Tomato , Timun , Kacang Bendi , Kacang Panjang , Kerabu Taugeh , Kerabu Mangga , Acar Timun & Nenas , Acar Buah , Rojak Buah – Buahan JERUK BUAH Mangga Sala ,Jeruk Salak , Jeruk Kelubi , Jeruk Pala , Jeruk Mangga Kulit , Jeruk Kedondong Hijau , Jeruk Betik & Jeruk Cermai SAMBAL TRADISIONAL Sambal Belacan , Sambal Kicap , Air Asam , Budu , Cencalok , Thai Chili Sauce , Chili Sauce & Tomato Sauce BERANIKA KEROPOK Keropok Ikan , Keropok Udang , Keropok Lekor , Keropok Sayur , Papadom TRADISONAL GULAI KAWAH Gulai Kawah Bukhari KANJI TEMPATAN Bubur Lambuk SUP Sup Ayam Berempah ( Daun Bawang , Bawang Goreng , Nasi Impit ,Roti , Kacang Goreng & Daun Sup ) GERAI RAMADHAN Mee Bandung ( Taukua , Tauge , Sawi , Bebola Ikan , Bebola Sotong , Cabai Potong & Telur Rebus ) GERAI RAMADHAN Penang Tradisional Koay Teow GERAI RAMADHAN Roti Jala atau Roti Canai ( Kari Ayam , Kuah Manis ) GERAI RAMADHAN Ayam Goreng Berempah GERAI RAMADHAN Kambing Panggang ( Black Paper , Rosemary & BBQ ) GERAI RAMADHAN Satay Ayam ( Timun , Bawang , Nasi Impit & Kuah Kacang ) GERAI RAMADHAN Ais Kacang & Cendol ( Kacang Merah , Jagung , Buah Attap , Agar-Agar , Puah Pala , Cincau , Cendol , Susu , Santan , Sirap Rose , Sarsi & Gula Merah ) HIDANGAN UTAMA Nasi Putih Nasi Briyani Daging Rendang Keling Ikan Gulai Masak Lemak Lemak Lala Taukua Masak Sambal Sayur Kailan Ikan Masin Telur Rebus Bersos MINUMAN PANAH RAJUNA Soya Gula Hitam , Soya Gula -

Annex a Open Clusters

Annex A Open Clusters Epidemiological investigations and contact tracing have uncovered links between cases. i. 6 of the confirmed cases (Cases 63131, 63184, 63185, 63186, 63187 and 63188) are linked to the Case 63131 cluster, with the most recent cases (Cases 63184, 63185, 63186, 63187 and 63188) linked to the cluster on 13 May. Case 63131 is a 50 year-old female Singaporean who works as a tutor at Learning Point. She was confirmed to have COVID-19 infection on 12 May. Cases 63184, 63185, 63186, 63187 and 63188 are students at Learning Point. ii. 3 of the confirmed cases (Cases 63096, 63122 and 63221) are linked to the Case 63096 cluster, with the most recent case (Case 63221) linked to the cluster on 14 May. Case 63096 is a 33 year-old male Philippines national who works as an operating theatre nurse at Sengkang General Hospital. He was confirmed to have COVID-19 infection on 11 May. Cases 63122 and 63221 are household contacts of Case 63096. iii. 59 of the confirmed cases (Cases 62873, 62940, 62941, 62942, 62945, 62971, 62972, 63005, 63015, 63026, 63047, 63055, 63059, 63060, 63061, 63070, 63071, 63072, 63074, 63084, 63091, 63094, 63095, 63097, 63098, 63100, 63109, 63115, 63117, 63118, 63119, 63125, 63126, 63128, 63129, 63132, 63135, 63136, 63138, 63139, 63140, 63141, 63146, 63148, 63149, 63150, 63165, 63167, 63169, 63177, 63178, 63179, 63180, 63181, 63191, 63192, 63194, 63195 and 63219) are linked to the Case 62873 cluster, with the most recent cases (Case 63177) linked to the cluster on 12 May, Cases 63165, 63167, 63169, 63178, 63179, 63180, 63181, 63191, 63194 and 63195 linked to the cluster on 13 May, and Cases 63192 and 63219 linked to the cluster on 14 May. -

Universiti Malaya Faculty of Business & Accountancy

APPENDIX 1 UNIVERSITI MALAYA FACULTY OF BUSINESS & ACCOUNTANCY MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION Dear Sir/Madam/Miss, This survey is conducted as partial requirement for completion of Master of Business Administration degree from the University of Malaya. It is targeted to tourists who has been visited to Kuala Lumpur ( KL ) to participate in this survey. This questionnaire asking about your experience during the visit to Kuala Lumpur (KL ) concerning the overall destination image, perceived quality of service, perceived value and behavior intention. The data collected from this questionnaire will be used for my research project and will be put into a written thesis. Please take a few minutes to participate in this important study by filling out and returning your questionnaire. Your response to each question in this questionnaire will only be analyzed in aggregate forms and be kept strictly confidential. In other words, individuals who respond to this questionnaire will not be identified. Your cooperation and support is greatly appreciated. If you need further information about the project, do not hesitate to contact me (undersign) or my supervisor Dr Norbani Che Ha at 03-79673998 or email at [email protected] Your kind cooperation and participation in this study is valued and highly appreciated. Prepared by, Lim Ai Sal 012- 2722087 [email protected] 110 Section A: About your perceptions and impressions 1. Below is a list of statement assessing your perception and your own experience of Kuala Lumpur (KL) as a travel destination. Please circle only ONE answer for each section that best represent your agreement with the statements on a scale 1-5. -

Supplementary Table S1: Complete Food Group and List Included in the Semi-Quantitative FFQ

Supplementary Table S1: Complete food group and list included in the semi-quantitative FFQ. A. Cereals & cereals products D. Eggs L. Traditional Malaysian ‘Kuih’ & 1. White rice 74. Boiled egg Confectionaries 2. Basmati rice 75. Fried egg 144. Fried & spicy traditional kuih 3. Brown rice 76. Salted egg (e.g.: curry puff/ samosa/ popia 4. Fried rice rolls/ vadai) 5. Rice/ ‘Nasi Dagang’ E. Vegetables 145. Fried & sweet traditional kuih 6. Rice/ ‘Nasi Arab’/ ‘Nasi Briyani’/ 77. Fried green leafy vegetables (e.g.: doughnut / ‘ham chi peng/ lad- ‘Nasi Jagung’/ ‘Nasi Minyak’/ ‘Nasi 78. Green leafy vegetables soup doo/ cakoi’) Tomato’ 79. Green leafy vegetables cooked 146. Grilled/ Steamed spicy tradi- 7. Rice cooked with coconut milk/ with coconut milk gravy (e.g.: curry/ tional kuih (e.g.: grilled glutinous ‘Nasi Lemak’ ‘lemak’) rice/ ‘cara berlauk/ meat pau’) 8. Chicken Rice 80. Green leafy vegetables cooked by 147. Grilled/ Steamed sweet tradi- 9. Rice/ ‘Nasi Kerabu’ steamed/ boiled tional kuih (e.g.: apam/ kuih ang 10. Plain Porridge 81. Fried cruciferous vegetables koo/ kaya pau/ kuih talam) 11. Porridge (e.g.: chicken porridge/ 82. Cruciferous vegetables soup 148. Sweet porridge (e.g.: durians fish porridge/ meat porridge/ lambuk 83 Cruciferous vegetables cooked porridge/ green beans porridge/ porridge) with coconut milk gravy (e.g.: curry/ sweet potato porridge) 12. Fried Noodles (‘mee/ mee-hoon/ ‘lemak’) 149. Cakes kueh-teow/ wantan mee’) 84. Cruciferous vegetables cooked 150. Pastry (e.g.: pie/ croissant) 13. Noodles cooked with gravy (e.g.: by steamed/ boiled 151. Jelly/ ‘agar-agar’ ‘hailam/ kicap/ kolok/ sizzling’) 85. Fried bean vegetables 152. -

Determinants of Eating at Local and Western Fast-Food Venues in an Urban Asian Population: a Mixed Methods Approach Nasheen Naidoo1, Rob M

Naidoo et al. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity (2017) 14:69 DOI 10.1186/s12966-017-0515-x RESEARCH Open Access Determinants of eating at local and western fast-food venues in an urban Asian population: a mixed methods approach Nasheen Naidoo1, Rob M. van Dam2,3, Sheryl Ng2, Chuen Seng Tan2, Shiqi Chen4, Jia Yi Lim4, Mei Fen Chan4, Ling Chew4 and Salome A. Rebello2* Abstract Background: Like several Southeast Asian countries, Singapore has a complex eating-out environment and a rising eating-out prevalence. However the determinants and drivers of eating-out in urban Asian environments are poorly understood. Methods: We examined the socio-demographic characteristics of persons who frequently ate away from home in local eateries called hawker centres and Western fast-food restaurants, using data from 1647 Singaporean adults participating in the National Nutrition Survey (NNS) 2010. We also assessed the underlying drivers of eating out and evaluated if these were different for eating at local eateries compared to Western fast-food restaurants using 18 focus group discussions of women (130 women). Results: Participants reported a high eating-out frequency with 77.3% usually eating either breakfast, lunch or dinner at eateries. Main venues for eating-out included hawker centres (61.1% usually ate at least 1 of 3 daily meals at this venue) and school/workplace canteens (20.4%). A minority of participants (1.9%) reported usually eating at Western fast-food restaurants. Younger participants and those of Chinese and Malay ethnicity compared to Indians were more likely to eat at Western fast-food restaurants. -

JURONG Heritage Trail

T he Jurong Heritage Trail is part of the National Heritage Board’s ongoing efforts » DISCOVER OUR SHARED HERITAGE to document and present the history and social memories of places in Singapore. We hope this trail will bring back fond memories for those who have worked, lived or played in the area, and serve as a useful source of information for new residents JURONG and visitors. HERITAGE TRAIL » CONTENTS » AREA MAP OF Early History of Jurong p. 2 Historical extent of Jurong Jurong The Orang Laut and early trade routes Early accounts of Jurong The gambier pioneers: opening up the interior HERITAGE TRAIL Evolution of land use in Jurong Growth of Communities p. 18 MARKED HERITAGE SITES Villages and social life Navigating Jurong Beginnings of industry: brickworks and dragon kilns 1. “60 sTalls” (六十档) AT YUNG SHENG ROAD ANd “MARKET I” Early educational institutions: village schools, new town schools and Nanyang University 2. AROUND THE JURONG RIVER Tide of Change: World War II p. 30 101 Special Training School 3. FORMER JURONG DRIVE-IN CINEMA Kranji-Jurong Defence Line Backbone of the Nation: Jurong in the Singapore Story p. 35 4. SCIENCE CENTRE SINGAPORE Industrialisation, Jurong and the making of modern Singapore Goh’s folly? Housing and building a liveable Jurong 5. FORMER JURONG TOWN HALL Heritage Sites in Jurong p. 44 Hawker centres in Jurong 6. JURONG RAILWAY Hong Kah Village Chew Boon Lay and the Peng Kang area 7. PANDAN RESERVOIR SAFTI Former Jurong Town Hall 8. JURONG HILL Jurong Port Jurong Shipyard Jurong Fishery Port 9. JURONG PORT AND SHIPYARD The Jurong Railway Jurong and Singapore’s waste management 10. -

MUSLIM VISITOR GUIDE HALAL DINING•PRAYERHALAL SPACES • CULTURE • STORIES to Singapore Your FOREWORD

Your MUSLIM VISITOR GUIDE to Singapore HALAL DINING • PRAYER SPACES • CULTURE • STORIES FIRST EDITION | 2020 | ENGLISH VERSION EDITION | 2020 FIRST FOREWORD Muslim-friendly Singapore P18 LITTLE INDIA Muslims make up 14 percent of Singapore’s population As a Muslim traveller, this guide provides you and it is no surprise that this island state offers a large with the information you need to enjoy your stay variety of Muslim-friendly gastronomic experiences. in Singapore — a city where your passions in life MASJID SULTAN P10 KAMPONG GLAM Many of these have been Halal certified by MUIS, are made possible. You may also download the P06 ORCHARD ROAD also known as the Islamic Religious Council of MuslimSG app and follow @halalSG on Twitter for Singapore (Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura). Visitors any Halal related queries while in Singapore. can also consider Muslim-owned food establishments throughout the city. Furthermore, mosques and – Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura (MUIS) musollahs around the island allow you to fulfill your P34 ESPLANADE religious obligations while you are on vacation. TIONG BAHRU P22 TIONGMARKET BAHRU P26 CHINATOWN P34 MARINA BAY CONTENTS 05 TIPS 26 CHINATOWN ORCHARD 06 ROAD 30 SENTOSA KAMPONG MARINA BAY & MAP OF SEVEN 10 GLAM 34 ESPLANADE NEIGHBOURHOODS This Muslim-friendly guide to the seven main LITTLE TRAVEL P30 SENTOSA neighbourhoods around 18 INDIA 38 ITINERARIES Singapore helps you make the best of your stay. TIONG HALAL RESTAURANT 22 BAHRU 42 DIRECTORY Tourism Court This guide was developed with inputs from writers Nur Safiah 1 Orchard Spring Lane Alias and Suffian Hakim, as well as CrescentRating, a leading Singapore 247729 authority on Halal travel. -

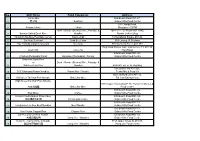

No. Stall Name Food Categories Address

No. Stall Name Food Categories Address Chi Le Ma 505 Beach Road #01-87, 1 吃了吗 Seafood Golden Mile Food Center 307 Changi Road, 2 Katong Laksa Laksa Singapore 419785 Duck / Goose (Stewed) Rice, Porridge & 168 Lor 1 Toa Payoh #01-1040, 3 Benson Salted Duck Rice Noodles Maxim Coffee Shop 4 Kampung Kia Blue Pea Nasi Lemak Nasi Lemak 10 Sengkang Square #01-26 5 Sin Huat Seafood Crab Bee Hoon 659 Lorong 35 Geylang 6 Hoy Yong Seafood Restaurant Cze Cha 352 Clementi Ave 2, #01-153 Haig Road Market and Food Centre, 13, #01-36 7 Chef Chik Cze Cha Haig Road 505 Beach Road #B1-30, 8 Charlie's Peranakan Food Eurasian / Peranakan / Nonya Golden Mile Food Centre Sean Kee Duck Rice or Duck / Goose (Stewed) Rice, Porridge & 9 Sia Kee Duck Rice Noodles 659-661Lor Lor 35 Geylang 665 Buffalo Rd #01-326, 10 545 Whampoa Prawn Noodles Prawn Mee / Noodle Tekka Mkt & Food Ctr 466 Crawford Lane #01-12, 11 Hill Street Tai Hwa Pork Noodle Bak Chor Mee Tai Hwa Eating House High Street Tai Wah Pork Noodle 531A Upper Cross St #02-16, Hong Lim Market & 12 大崋肉脞麵 Bak Chor Mee Food Centre 505 Beach Road #B1-49, 13 Kopi More Coffee Golden Mile Food Centre Hainan Fried Hokkien Prawn Mee 505 Beach Road #B1-34, 14 海南福建炒虾麵 Fried Hokkien Mee Golden Mile Food Centre 505 Beach Road #B1-21, 15 Longhouse Lim Kee Beef Noodles Beef Noodle Golden Mile Food Centre 505 Beach Road #01-73, 16 Yew Chuan Claypot Rice Claypot Rice Golden Mile Food Centre Da Po Curry Chicken Noodle 505 Beach Road #B1-53, 17 大坡咖喱鸡面 Curry Mee / Noodles Golden Mile Food Centre Heng Kee Curry Chicken Noodle 531A -

Daikiya Group Holdings Limited

Daikiya Group Holdings Limited Daikiya Group Holdings Limited (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) Stock Code: 6813 Daikiya Group Holdings Limited SHARE OFFER Sole Sponsor Sole Global Coordinator Joint Bookrunners IMPORTANT If you are in any doubt about any of the contents of this prospectus, you should seek independent professional advice. Daikiya Group Holdings Limited 大 喜 屋 集 團 控 股 有 限 公 司 (incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) LISTINGONTHEMAINBOARDOF THE STOCK EXCHANGE OF HONG KONG LIMITED BY WAY OF SHARE OFFER Number of Offer Shares : 100,000,000 Shares (subject to the Over-allotment Option) Number of Hong Kong Offer Shares : 10,000,000 Shares (subject to reallocation) Number of International Placing Shares : 90,000,000 Shares (subject to reallocation and the Over- allotment Option) Offer Price : not more than HK$2.00 per Offer Share and not less than HK$1.60 per Offer Share, plus brokerage fee of 1%, SFC transaction levy of 0.0027% and Stock Exchange trading fee of 0.005% (payable in full on application in Hong Kong dollars and subject to refund) Nominal Value : HK$0.01 per Share Stock Code : 6813 Sole Sponsor Sole Global Coordinator Joint Bookrunners Joint Lead Managers Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited, The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited and Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this prospectus, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this prospectus. -

Mong Kok Job Expo Building a Multi-Culture Workplace

Mong Kok Job Expo Building a Multi-culture Workplace Date: 21-22 March 2018 (Wednesday and Thursday) Time: 11:00 a.m. – 5:30 p.m. (Last admission at 5:00 p.m.) Venue: MacPherson Stadium, 1/F, 38 Nelson Street, Mong Kok (MTR Mong Kok Station Exit E2) Employers conduct on-the-spot recruitment; Training bodies introduce training courses; Mini exhibition provides useful information Offering about 7 600 vacancies! On-site interpretation and support services for Ethnic Minority are available Free admission! Welcome to join! You can get a souvenir for joining the event! Subscribe for latest information on large-scale job fairs at “MyGovHK” (www.gov.hk/mygovhk/en)! 21 March 2018 (Wednesday) Participating Organisation Job Vacancy Location The Excelsior Hong Kong Commis Causeway Bay Waiter/Waitress Causeway Bay Room Attendant Causeway Bay Laundry Coordinator Causeway Bay Dish Washer Causeway Bay Jones Lang LaSalle Limited Customer Services Officer (Full-time / Central Part-time) Central , Kowloon Station , Facilities Assistant (Full-time / Part-time) Sheung Wan , Tseung Kwan O Central , Chek Lap Kok , Technician Kowloon Station , Mong Kok , Tung Chung Administrator Aberdeen Receptionist Aberdeen , Central Aberdeen , Kwun Tong , Facilities Officer Mong Kok 1 Participating Organisation Job Vacancy Location Physical Health Centre Hong Receptionist (Full-time / Part-time) Anywhere in H.K. Kong Limited Cleaner (Full-time / Part-time) Anywhere in H.K. Amoy Food Limited Production Operator (Frozen Foods) Tai Po Forklift Truck Driver Tai Po Cleaner Tai Po Production Operator (Soy & Sauce) Tai Po Distribution Helper Anywhere in H.K. Fairwood Fast Food Ltd. Production Assistant (Full-time / Part-time) Tai Po Cleaner Tai Po Cook I/Cook II Anywhere in H.K. -

BETTER Food BETTER People BETTER Life

KOUFU GROUP LIMITED GROUP KOUFU KOUFU GROUP LIMITED (Company Registration No: 201732833D) ANNUAL REPORT REPORT ANNUAL 18 Woodlands Terrace Singapore 738443 Tel: +65 6506 0161 Fax: +65 6752 1811 www.koufu.com.sg 2018 BETTER food BETTER people BETTER life 2018 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF Contents 01 02 03 04 OUR ABOUT KOUFU ISLANDWIDE CORPORATE CHAIRMAN’S GROUP LIMITED NETWORK MILESTONES MESSAGE 07 09 10 12 FINANCIAL & BOARD OF KEY FINANCIAL OPERATIONS DIRECTORS MANAGEMENT HIGHLIGHTS REVIEW 16 17 21 22 OUR AWARDS AND MULTI-BRAND INVESTOR GROUP ACCOLADES STRATEGY RELATIONS STRUCTURE 23 24 59 150 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS CORPORATE AND NOTICE OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE ADDITIONAL AGM AND INFORMATION REPORT INFORMATION PROXY FORM ANNUAL REPORT 2018 KOUFU GROUP LIMITED 01 ABOUT Koufu GROUP LIMITED Established in 2002 and listed on the Mainboard of the SGX-ST since July 2018, Koufu Group Limited (“Koufu”, 口福集团有限公司, or together with its subsidiaries, the “Group”) is one of the most established and largest operators and managers of food courts and coffee shops in Singapore, with a presence in Macau. Since its inception, Koufu’s philosophy has been to integrate modern management discipline into its business while retaining the traditional coffee shop culture, with particular emphasis on providing patrons with value for money dining options in a comfortable environment – congruent with its core values in its vision towards “Better Food”, “Better People”, “Better Life”. Koufu’s business comprises two segments – outlet & mall management and F&B retail. Under the outlet & mall management business segment, Koufu operates and/or manages food courts, coffee shops, a hawker centre and a commercial mall. -

![Baba Hawker [ Vegan Menu ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6896/baba-hawker-vegan-menu-2206896.webp)

Baba Hawker [ Vegan Menu ]

BABA HAWKER [ VEGAN MENU ] A traditional Malay blend of South Indian and South East Asian cuisine This is a family cooking, family business, our chef and matriarch Mila began developing a passion for cooking from an earlier age (when she wasn’t climbing trees to avoid getting eaten by Tigers roaming her native borneo jungle, walks to school were exciting!). As her powers grew, she focused upon Baba-Nyonya cuisine. This style, unique to the Malay Archipelago originated when early Chinese settlers took inspiration from Malaysian, South Indian and Thai cooking to create a seamless and delicious new cooking style, centuries before any fancy chef coined the term ‘fusion’. Now, we are delighted to bring this cuisine (with our Happy flair) to Melbourne’s heart of food and culture, Brunswick. We really hope you enjoy your taste of Baba Hawker. Starters Curry Puff ( DF, mild ) We make two types of pastry, then painstakingly roll, and re-roll them together to create just the right crunchy 2.5 flaky texture, it’s a serious undertaking involving the whole family but worth it. Filled with lightly spiced veggies, sold individually, about the size of a small pasty. Vegan Otah Otah (4 pieces, GF, DF, mild) 6 Four thin strips of vegan fish spiced curry, turmeric, & lemongrass with toasted within banana leaves. Pakora Bites (8 pieces, GF, mild) 6 Deep fried vegetables, spiced rice and moong dhaal bites. Served with sauce. Nasi Lemak (gf) Malaysia unofficial national dish, a little bit of Vegan Chicken Rendang ( medium ) 17 everything, think spicy boxless Bento. Fragrant rice dish Vegan Beef Rendang ( medium ) 17 cooked in coconut milk and pandan leaf.