Download Report 2015–17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Landscapes of Exploration' Education Pack

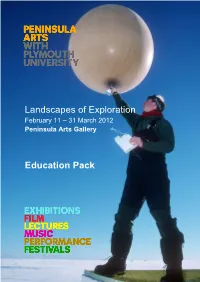

Landscapes of Exploration February 11 – 31 March 2012 Peninsula Arts Gallery Education Pack Cover image courtesy of British Antarctic Survey Cover image: Launch of a radiosonde meteorological balloon by a scientist/meteorologist at Halley Research Station. Atmospheric scientists at Rothera and Halley Research Stations collect data about the atmosphere above Antarctica this is done by launching radiosonde meteorological balloons which have small sensors and a transmitter attached to them. The balloons are filled with helium and so rise high into the Antarctic atmosphere sampling the air and transmitting the data back to the station far below. A radiosonde meteorological balloon holds an impressive 2,000 litres of helium, giving it enough lift to climb for up to two hours. Helium is lighter than air and so causes the balloon to rise rapidly through the atmosphere, while the instruments beneath it sample all the required data and transmit the information back to the surface. - Permissions for information on radiosonde meteorological balloons kindly provided by British Antarctic Survey. For a full activity sheet on how scientists collect data from the air in Antarctica please visit the Discovering Antarctica website www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk and select resources www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk has been developed jointly by the Royal Geographical Society, with IBG0 and the British Antarctic Survey, with funding from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. The Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) supports geography in universities and schools, through expeditions and fieldwork and with the public and policy makers. Full details about the Society’s work, and how you can become a member, is available on www.rgs.org All activities in this handbook that are from www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk will be clearly identified. -

Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate

Freistaat Sachsen State Chancellery Message and Greeting ................................................................................................................................................. 2 State and People Delightful Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate ......................................................................................... 5 The Saxons – A people unto themselves: Spatial distribution/Population structure/Religion .......................... 7 The Sorbs – Much more than folklore ............................................................................................................ 11 Then and Now Saxony makes history: From early days to the modern era ..................................................................................... 13 Tabular Overview ........................................................................................................................................................ 17 Constitution and Legislature Saxony in fine constitutional shape: Saxony as Free State/Constitution/Coat of arms/Flag/Anthem ....................... 21 Saxony’s strong forces: State assembly/Political parties/Associations/Civic commitment ..................................... 23 Administrations and Politics Saxony’s lean administration: Prime minister, ministries/State administration/ State budget/Local government/E-government/Simplification of the law ............................................................................... 29 Saxony in Europe and in the world: Federalism/Europe/International -

Scott's Discovery Expedition

New Light on the British National Antarctic Expedition (Scott’s Discovery Expedition) 1901-1904. Andrew Atkin Graduate Certificate in Antarctic Studies (GCAS X), 2007/2008 CONTENTS 1 Preamble 1.1 The Canterbury connection……………...………………….…………4 1.2 Primary sources of note………………………………………..………4 1.3 Intent of this paper…………………………………………………...…5 2 Bernacchi’s road to Discovery 2.1 Maria Island to Melbourne………………………………….…….……6 2.2 “.…that unmitigated fraud ‘Borky’ ……………………….……..….….7 2.3 Legacies of the Southern Cross…………………………….…….…..8 2.4 Fellowship and Authorship………………………………...…..………9 2.5 Appointment to NAE………………………………………….……….10 2.6 From Potsdam to Christchurch…………………………….………...11 2.7 Return to Cape Adare……………………………………….….…….12 2.8 Arrival in Winter Quarters-establishing magnetic observatory…...13 2.9 The importance of status………………………….……………….…14 3 Deeds of “Derring Doe” 3.1 Objectives-conflicting agendas…………………….……………..….15 3.2 Chivalrous deeds…………………………………….……………..…16 3.3 Scientists as Heroes……………………………….…….……………19 3.4 Confused roles……………………………….……..………….…...…21 3.5 Fame or obscurity? ……………………………………..…...….……22 2 4 “Scarcely and Exhibition of Control” 4.1 Experiments……………………………………………………………27 4.2 “The Only Intelligent Transport” …………………………………….28 4.3 “… a blasphemous frame of mind”……………………………….…32 4.4 “… far from a picnic” …………………………………………………34 4.5 “Usual retine Work diggin out Boats”………...………………..……37 4.6 Equipment…………………………………………………….……….38 4.8 Reflections on management…………………………………….…..39 5 “Walking to Christchurch” 5.1 Naval routines………………………………………………………….43 -

Representations of Antarctic Exploration by Lesser Known Heroic Era Photographers

Filtering ‘ways of seeing’ through their lenses: representations of Antarctic exploration by lesser known Heroic Era photographers. Patricia Margaret Millar B.A. (1972), B.Ed. (Hons) (1999), Ph.D. (Ed.) (2005), B.Ant.Stud. (Hons) (2009) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science – Social Sciences. University of Tasmania 2013 This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. ………………………………….. ………………….. Patricia Margaret Millar Date This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. ………………………………….. ………………….. Patricia Margaret Millar Date ii Abstract Photographers made a major contribution to the recording of the Heroic Era of Antarctic exploration. By far the best known photographers were the professionals, Herbert Ponting and Frank Hurley, hired to photograph British and Australasian expeditions. But a great number of photographs were also taken on Belgian, German, Swedish, French, Norwegian and Japanese expeditions. These were taken by amateurs, sometimes designated official photographers, often scientists recording their research. Apart from a few Pole-reaching images from the Norwegian expedition, these lesser known expedition photographers and their work seldom feature in the scholarly literature on the Heroic Era, but they, too, have their importance. They played a vital role in the growing understanding and advancement of Antarctic science; they provided visual evidence of their nation’s determination to penetrate the polar unknown; and they played a formative role in public perceptions of Antarctic geopolitics. -

Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) in a Coastal Plain Area in the State of Paraná, Brazil

62 TROP. LEPID. RES., 26(2): 62-67, 2016 LEVISKI ET AL.: Butterflies in Paraná Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) in a coastal plain area in the state of Paraná, Brazil Gabriela Lourenço Leviski¹*, Luziany Queiroz-Santos¹, Ricardo Russo Siewert¹, Lucy Mila Garcia Salik¹, Mirna Martins Casagrande¹ and Olaf Hermann Hendrik Mielke¹ ¹ Laboratório de Estudos de Lepidoptera Neotropical, Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Caixa Postal 19.020, 81.531-980, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]٭ Abstract: The coastal plain environments of southern Brazil are neglected and poorly represented in Conservation Units. In view of the importance of sampling these areas, the present study conducted the first butterfly inventory of a coastal area in the state of Paraná. Samples were taken in the Floresta Estadual do Palmito, from February 2014 through January 2015, using insect nets and traps for fruit-feeding butterfly species. A total of 200 species were recorded, in the families Hesperiidae (77), Nymphalidae (73), Riodinidae (20), Lycaenidae (19), Pieridae (7) and Papilionidae (4). Particularly notable records included the rare and vulnerable Pseudotinea hemis (Schaus, 1927), representing the lowest elevation record for this species, and Temenis huebneri korallion Fruhstorfer, 1912, a new record for Paraná. These results reinforce the need to direct sampling efforts to poorly inventoried areas, to increase knowledge of the distribution and occurrence patterns of butterflies in Brazil. Key words: Atlantic Forest, Biodiversity, conservation, inventory, species richness. INTRODUCTION the importance of inventories to knowledge of the fauna and its conservation, the present study inventoried the species of Faunal inventories are important for providing knowledge butterflies of the Floresta Estadual do Palmito. -

The Centenary of the Scott Expedition to Antarctica and of the United Kingdom’S Enduring Scientific Legacy and Ongoing Presence There”

Debate on 18 October: Scott Expedition to Antarctica and Scientific Legacy This Library Note provides background reading for the debate to be held on Thursday, 18 October: “the centenary of the Scott Expedition to Antarctica and of the United Kingdom’s enduring scientific legacy and ongoing presence there” The Note provides information on Antarctica’s geography and environment; provides a history of its exploration; outlines the international agreements that govern the territory; and summarises international scientific cooperation and the UK’s continuing role and presence. Ian Cruse 15 October 2012 LLN 2012/034 House of Lords Library Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of the House of Lords and their personal staff, to provide impartial, politically balanced briefing on subjects likely to be of interest to Members of the Lords. Authors are available to discuss the contents of the Notes with the Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. Any comments on Library Notes should be sent to the Head of Research Services, House of Lords Library, London SW1A 0PW or emailed to [email protected]. Table of Contents 1.1 Geophysics of Antarctica ....................................................................................... 1 1.2 Environmental Concerns about the Antarctic ......................................................... 2 2.1 Britain’s Early Interest in the Antarctic .................................................................... 4 2.2 Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration ....................................................................... -

Vor Den Anschlägen

Fernsehen 14 Tage TV-Programm 15.11. bis 28.11.2018 Themenabend „Saat des Terrors“ am 21.11. bei der ARD Vor den Anschlägen Kaputte Krieger Picnic at Hanging Rock Feature über die Folgen der Bundeswehr- Der Stoff des australischen Mystery- Einsätze am Hindukusch im Kulturradio Klassikers als neue Serie auf DVD Tip2418_001 1 01.11.18 16:02 FERNSEHEN 15. – 28.11. TELEVISOR Preisverdächtig VON TERESA SCHOMBURG Schon wieder eine Preisverleihung. Gefühlt läuft mittlerweile jeden zweiten Tag eine, am 16. November ist der Bambi dran, das Erste ist live dabei. Als Genre ist so eine Verleihung ja eher weniger attrak- UNIVERSUM tiv. Entweder feiert sich eine Grup- FOTO pe kräftig selbst wie letztens am 7. Oktober beim Deutschen Comedy- preis, zum ersten Mal live auf RTL. GMBH DIWAFILM SWR/ Oder das Auswahlprinzip ist arg FOTO fragwürdig wie beim glücklicher- Als Agentin in Pakistan muss Christiane Paul (Foto, Mi.) sich mit vielen Männer rumschlagen weise abgeschafften Echo. Und meist werden elendig viele Preise THEMENABEND in abstrusen Kategorien (Was soll der „Millenium“-Bambi sein?) an einen überschaubaren, wiederkeh- renden Kreis von Personen verge- Das Spionage-Debakel ben, die sich in langen Reden bei allen bedanken, die je ihren Le- Der investigative Spielfilm „Saat des Terrors“ und eine Doku bensweg kreuzten. Von der Oma decken üble Versäumnisse westlicher Geheimdienste auf bis zum Kaffeemaschinenherstel- ler, ohne den sie es nie geschafft umbai am 26. November 2008. Am ten James Logan Davies (Crispin Glover), hätten, überhaupt bis zu diesem M Bahnhof der indischen Metropole die westlichen Geheimdienste zu narren. Punkt der Veranstaltung wach zu beginnt eine Serie von Bombenanschlä- Doch keiner nimmt ihre Warnungen bleiben. -

Preliminary Analysis of the Diurnal Lepidoptera Fauna of the Três Picos State Park, Rio De Janeiro, Brazil, with a Note on Parides Ascanius (Cramer, 1775)

66 TROP. LEPID. RES., 21(2):66-79, 2011 SOARES ET AL.: Butterflies of Três Picos PRELIMINARY ANALYSIS OF THE DIURNAL LEPIDOPTERA FAUNA OF THE TRÊS PICOS STATE PARK, RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL, WITH A NOTE ON PARIDES ASCANIUS (CRAMER, 1775) Alexandre Soares1, Jorge M. S. Bizarro2, Carlos B. Bastos1, Nirton Tangerini1, Nedyson A. Silva1, Alex S. da Silva1 and Gabriel B. Silva1 1Departamento de Entomologia, Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Quinta da Boa Vista s/n, 20940-040 RIO DE JANEIRO-RJ, Brasil. 2Reserva Ecológica de Guapiaçu, Caixa Postal 98112, 28680-000 CACHOEIRAS DE MACACU-RJ, Brasil. Correspondence to Alexandre Soares: [email protected] Abstract - This paper deals with the butterfly fauna of the Três Picos State Park (PETP) area, Rio de Janeiro State (RJ), Brazil, sampled by an inventory of the entomological collections housed in the Museu Nacional/UFRJ (MNRJ) and a recent field survey at Reserva Ecologica de Guapiaçu (REGUA). The lowland butterfly fauna (up to 600m) is compared for both sites and observations are presented onParides ascanius (Cramer, 1775). Resumo - Apresentam-se dados provisórios sobre a Biodiversidade da fauna de borboletas do Parque Estadual dos Três Picos (PETP), Estado do Rio de Janeiro (RJ), Brasil, inventariada mediante o recurso a dados de etiquetas do acervo da coleção entomológica do Museu Nacional/UFRJ (MNRJ) e uma amostragem de campo executada na Reserva Ecologica de Guapiaçu (REGUA). A riqueza da fauna de borboletas da floresta ombrófila densa de baixada (até 600m) é comparada entre ambas as localidades, registrando-se uma extensão recente da área de ocorrência de Parides ascanius (Cramer, 1775). -

Underground Mines, Down to 200 M, 1500 Km Length • 311 Mio

New challenges for mine rescue in Saxony Prof. Dr. Bernhard Cramer, Oberberghauptmann Chief Mine Inspector of Saxony, Freiberg Mining Authority of Saxony — Sächsisches Oberbergamt • mining concessions — permissions for exploration (Erlaubnis), approval for mining (Bewilligung) • collection of royalties (Feldes- und Förderabgaben) • operational plans for mining activity — revision and authorization • mine inspection — safety, environment, health • police authoritiy — for protection against threats to public safety from old mines, tailings and subsurface cavities responsibilities in mine rescue mine safety, operational plan mining company maintained by employer's liability insurance association mine rescue (BGRCI) central office mining authority mine rescue supervision, control, common tasks approval of (training, test of technical operational plans equipment) guidelines, advice to companies basis for mine rescue in Germany Guidelines of the Central Office for Mine Rescue (Hauptstelle GR) of the employer's liability insurance association for mining (BGRCI) concerning organisation, equipment and operation of mine rescue, April 2006 1. Scope 2. Tasks of mine rescue 3. Structure of mine rescue 4. Organisation and equipment of mine rescue 5. Mission and procedure of mine rescue 6. Final clause Attachments 1 Standardübung 2 Übung in Flammenschutzkleidung 3 Tragezeitbegrenzung nach Anlage 2 der BGR 190 „Benutzung von Atemschutzgeräten“ 4 Einsatzzeittabelle für Grubenwehren im Salzbergbau 5 Sofortmeldung über Einsätze 6a Meldung I über den Einsatz -

The Ecological Role of Extremely Long-Proboscid Neotropical Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae) in Plant-Pollinator Networks

Arthropod-Plant Interactions DOI 10.1007/s11829-015-9379-7 ORIGINAL PAPER The ecological role of extremely long-proboscid Neotropical butterflies (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae) in plant-pollinator networks 1 2 1 J. A.-S. Bauder • A. D. Warren • H. W. Krenn Received: 30 August 2014 / Accepted: 8 April 2015 Ó The Author(s) 2015. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Extremely long proboscides of insect flower Introduction visitors have been regarded as an example of a coevolu- tionary arms race, assuming that these insects act as effi- Many scientists have pondered over the evolutionary pro- cient pollinators for their nectar host plants. However, the cesses that led to the development of particularly elongate effect of proboscis length on generalized or specialized proboscides in flower-visiting insects (Darwin 1862; flower use remains unclear and the efficiency of butterfly Johnson 1997; Johnson and Anderson 2010; Muchhala and pollination is ambiguous. Neotropical Hesperiidae feature a Thomson 2009; Nilsson 1988, 1998; Pauw et al. 2009; surprising variation of proboscis length, which makes them Rodrı´guez-Girone´s and Llandres 2008; Rodrı´guez-Girone´s a suitable study system to elucidate the role of extremely and Santamarı´a 2007; Wasserthal 1997, 1998; Whittall and long-proboscid insects in plant-pollinator networks. The Hodges 2007). The most widely accepted hypothesis for results of this study show that skippers with longer pro- the evolution of extreme mouthpart lengths is that they boscides visit plant species with deep-tubed flowers to take coevolved with long nectar spurs of angiosperms. In this up food, but do not pollinate them. -

Dritten Reich”

4. Mit Charakterst¨arke und Integrit¨at ubernommene¨ Verantwortung im “Dritten Reich” 4.1 Die ersten Jahre der nationalsozialistischen Diktatur Das Jahr 1933 begann mit der wohl folgenschwersten politischen Ver¨anderung Deutschlands (zumindest) im 20. Jahrhundert – der “Machtergreifung” durch die Nationalsozialisten am 30. Januar 77 78 1933: Reichskanzler Heinrich Bruning¨ , der aufgrund seiner strik- ten Sparpolitik ohnehin nicht popul¨ar war, verlor u. a. wegen der Osthilfeverordnung und des Verbots der SA die Unterstutzung¨ des Reichspr¨asidenten Paul von Hindenburg, fur¨ dessen am 10. April 1932 im zweiten Wahlgang (gegen Adolf Hitler und Ernst Th¨almann) erfolgte Wiederwahl er sich sehr stark engagiert hatte. Auf Betrei- ben des (parteilosen) Generals Kurt von Schleicher musste Bruning¨ am 30. Mai 1932 zurucktreten¨ – nach seinen eigenen Worten “hun- dert Meter vor dem Ziel”. Zu seinem Nachfolger ernannte Hinden- burg Franz von Papen79. Nach den Reichstagswahlen vom 6. No- vember 1932, aufgrund deren (ebenso wie bei der Reichstagswahl vom 31. Juli 1932) wiederum keine arbeitsf¨ahige Koalition m¨oglich war, trat das Kabinett Papen am 17. November 1932 zuruck.¨ Nach ergebnislosen Verhandlungen mit Hitler wurde Schleicher am 3. De- zember 1932 zum Reichskanzler berufen und mit der Bildung eines Pr¨asidialkabinetts beauftragt. Hinter seinem Rucken¨ verhandelte je- doch Papen am 22. Januar 1933 im Auftrage Hindenburgs mit Hitler uber¨ dessen Berufung zum Reichskanzler. Nach einem Gespr¨ach mit 77 Der Anfang dieses Abschnitts ist aus Jurgen¨ Elstrodt, Norbert Schmitz: Geschichte der Mathematik an der Universit¨at Munster,¨ Teil I: 1773 – 1945, Munster,¨ 2008, S. 54 ff., ubernommen.¨ 78 Geboren am 26. November 1885 in Munster,¨ Abitur am Gymnasium Pauli- num; in der Weimarer Republik fuhrender¨ Vertreter der Zentrumspartei. -

One Hundred Years of Chemical Warfare: Research

Bretislav Friedrich · Dieter Hoffmann Jürgen Renn · Florian Schmaltz · Martin Wolf Editors One Hundred Years of Chemical Warfare: Research, Deployment, Consequences One Hundred Years of Chemical Warfare: Research, Deployment, Consequences Bretislav Friedrich • Dieter Hoffmann Jürgen Renn • Florian Schmaltz Martin Wolf Editors One Hundred Years of Chemical Warfare: Research, Deployment, Consequences Editors Bretislav Friedrich Florian Schmaltz Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Max Planck Institute for the History of Society Science Berlin Berlin Germany Germany Dieter Hoffmann Martin Wolf Max Planck Institute for the History of Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Science Society Berlin Berlin Germany Germany Jürgen Renn Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Berlin Germany ISBN 978-3-319-51663-9 ISBN 978-3-319-51664-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-51664-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017941064 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/), which permits any noncom- mercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.