Scott's Discovery Expedition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Landscapes of Exploration' Education Pack

Landscapes of Exploration February 11 – 31 March 2012 Peninsula Arts Gallery Education Pack Cover image courtesy of British Antarctic Survey Cover image: Launch of a radiosonde meteorological balloon by a scientist/meteorologist at Halley Research Station. Atmospheric scientists at Rothera and Halley Research Stations collect data about the atmosphere above Antarctica this is done by launching radiosonde meteorological balloons which have small sensors and a transmitter attached to them. The balloons are filled with helium and so rise high into the Antarctic atmosphere sampling the air and transmitting the data back to the station far below. A radiosonde meteorological balloon holds an impressive 2,000 litres of helium, giving it enough lift to climb for up to two hours. Helium is lighter than air and so causes the balloon to rise rapidly through the atmosphere, while the instruments beneath it sample all the required data and transmit the information back to the surface. - Permissions for information on radiosonde meteorological balloons kindly provided by British Antarctic Survey. For a full activity sheet on how scientists collect data from the air in Antarctica please visit the Discovering Antarctica website www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk and select resources www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk has been developed jointly by the Royal Geographical Society, with IBG0 and the British Antarctic Survey, with funding from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. The Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) supports geography in universities and schools, through expeditions and fieldwork and with the public and policy makers. Full details about the Society’s work, and how you can become a member, is available on www.rgs.org All activities in this handbook that are from www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk will be clearly identified. -

Of Penguins and Polar Bears Shapero Rare Books 93

OF PENGUINS AND POLAR BEARS Shapero Rare Books 93 OF PENGUINS AND POLAR BEARS EXPLORATION AT THE ENDS OF THE EARTH 32 Saint George Street London W1S 2EA +44 20 7493 0876 [email protected] shapero.com CONTENTS Antarctica 03 The Arctic 43 2 Shapero Rare Books ANTARCTIca Shapero Rare Books 3 1. AMUNDSEN, ROALD. The South Pole. An account of “Amundsen’s legendary dash to the Pole, which he reached the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the “Fram”, 1910-1912. before Scott’s ill-fated expedition by over a month. His John Murray, London, 1912. success over Scott was due to his highly disciplined dogsled teams, more accomplished skiers, a shorter distance to the A CORNERSTONE OF ANTARCTIC EXPLORATION; THE ACCOUNT OF THE Pole, better clothing and equipment, well planned supply FIRST EXPEDITION TO REACH THE SOUTH POLE. depots on the way, fortunate weather, and a modicum of luck”(Books on Ice). A handsomely produced book containing ten full-page photographic images not found in the Norwegian original, First English edition. 2 volumes, 8vo., xxxv, [i], 392; x, 449pp., 3 folding maps, folding plan, 138 photographic illustrations on 103 plates, original maroon and all full-page images being reproduced to a higher cloth gilt, vignettes to upper covers, top edges gilt, others uncut, usual fading standard. to spine flags, an excellent fresh example. Taurus 71; Rosove 9.A1; Books on Ice 7.1. £3,750 [ref: 96754] 4 Shapero Rare Books 2. [BELGIAN ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION]. Grande 3. BELLINGSHAUSEN, FABIAN G. VON. The Voyage of Fete Venitienne au Parc de 6 a 11 heurs du soir en faveur de Captain Bellingshausen to the Antarctic Seas 1819-1821. -

Written by Andy Baird, Education Officer, TMAG © Tasmanian

EDUCATION KIT Written by Andy Baird, Education Officer, TMAG 1 © Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery 2006 CONTENTS Introduction The exhibition Background information Earliest Perceptions The Southern Ocean Wildlife in Motion Diorama The sub-Antarctic islands Antarctica: The continent of Ice Humans in the Antarctic region: why people go there Theatrette featuring Frank Hurley’s stereoscopic photography Humans in the Antarctic region: how people live there Teacher’s notes & exhibition guides Teacher’s notes Quick Guide to program suitability Exhibition Guides and programs offered by TMAG, including Curriculum focus, Key Learning Outcomes, Key Ideas, Museum and Classroom Activities 5 key themes: 1 Life in the Freezer: A day in the life of Antarctic animals 2 Apples in Antarctica: Humans in the ice box polar innovation in how people live and work in the region 3 From Whaling to Wilderness? The changing values of natural resource management in the region 4 Climate Change: Messages from the Frozen Continent 5 Underwater Wonderland: Biodiversity in the Southern Ocean Conundrum sheets, self-guided tours on diverse themes Resources • Floor map of exhibition • Overall map of region • Earliest perceptions map • Diagram of bathymetry of Southern Ocean • Captain Cook Sheet, The Mercury Newspaper • Whale Media Archive • Web of Life diagram • Southern Ocean Biomass • Shelter in Antarctica • Wind chill chart • Engine of the oceans: ocean circulation • Under the ice: cross section through Antarctica • Joseph Hatch product labels Visiting TMAG Education visit guidelines, booking procedures page 2 EDUCATION KIT Introduction The following material has been developed by the Education section of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery to support the exhibition Islands to Ice: The Great Southern Ocean and Antarctica. -

Navigation on Shackleton's Voyage to Antarctica

Records of the Canterbury Museum, 2019 Vol. 33: 5–22 © Canterbury Museum 2019 5 Navigation on Shackleton’s voyage to Antarctica Lars Bergman1 and Robin G Stuart2 1Saltsjöbaden, Sweden 2Valhalla, New York, USA Email: [email protected] On 19 January 1915, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, under the leadership of Sir Ernest Shackleton, became trapped in their vessel Endurance in the ice pack of the Weddell Sea. The subsequent ordeal and efforts that lead to the successful rescue of all expedition members are the stuff of legend and have been extensively discussed elsewhere. Prior to that time, however, the voyage had proceeded relatively uneventfully and was dutifully recorded in Captain Frank Worsley’s log and work book. This provides a window into the navigational methods used in the day-to- day running of the ship by a master mariner under normal circumstances in the early twentieth century. The conclusions that can be gleaned from a careful inspection of the log book over this period are described here. Keywords: celestial navigation, dead reckoning, double altitudes, Ernest Shackleton, Frank Worsley, Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, Mercator sailing, time sight Introduction On 8 August 1914, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic passage in the 22½ foot (6.9 m) James Caird to Expedition under the leadership of Sir Ernest seek rescue from South Georgia. It is ultimately Shackleton set sail aboard their vessel the steam a tribute to Shackleton’s leadership and Worsley’s yacht (S.Y.) Endurance from Plymouth, England, navigational skills that all survived their ordeal. with the goal of traversing the Antarctic Captain Frank Worsley’s original log books continent from the Weddell to Ross Seas. -

Antarctic Peninsula

Hucke-Gaete, R, Torres, D. & Vallejos, V. 1997c. Entanglement of Antarctic fur seals, Arctocephalus gazella, by marine debris at Cape Shirreff and San Telmo Islets, Livingston Island, Antarctica: 1998-1997. Serie Científica Instituto Antártico Chileno 47: 123-135. Hucke-Gaete, R., Osman, L.P., Moreno, C.A. & Torres, D. 2004. Examining natural population growth from near extinction: the case of the Antarctic fur seal at the South Shetlands, Antarctica. Polar Biology 27 (5): 304–311 Huckstadt, L., Costa, D. P., McDonald, B. I., Tremblay, Y., Crocker, D. E., Goebel, M. E. & Fedak, M. E. 2006. Habitat Selection and Foraging Behavior of Southern Elephant Seals in the Western Antarctic Peninsula. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2006, abstract #OS33A-1684. INACH (Instituto Antártico Chileno) 2010. Chilean Antarctic Program of Scientific Research 2009-2010. Chilean Antarctic Institute Research Projects Department. Santiago, Chile. Kawaguchi, S., Nicol, S., Taki, K. & Naganobu, M. 2006. Fishing ground selection in the Antarctic krill fishery: Trends in patterns across years, seasons and nations. CCAMLR Science, 13: 117–141. Krause, D. J., Goebel, M. E., Marshall, G. J., & Abernathy, K. (2015). Novel foraging strategies observed in a growing leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx) population at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Animal Biotelemetry, 3:24. Krause, D.J., Goebel, M.E., Marshall. G.J. & Abernathy, K. In Press. Summer diving and haul-out behavior of leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) near mesopredator breeding colonies at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Marine Mammal Science.Leppe, M., Fernandoy, F., Palma-Heldt, S. & Moisan, P 2004. Flora mesozoica en los depósitos morrénicos de cabo Shirreff, isla Livingston, Shetland del Sur, Península Antártica, in Actas del 10º Congreso Geológico Chileno. -

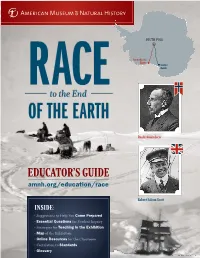

Educator's Guide

SOUTH POLE Amundsen’s Route Scott’s Route Roald Amundsen EDUCATOR’S GUIDE amnh.org/education/race Robert Falcon Scott INSIDE: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources for the Classroom • Correlation to Standards • Glossary ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Who would be fi rst to set foot at the South Pole, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen or British Naval offi cer Robert Falcon Scott? Tracing their heroic journeys, this exhibition portrays the harsh environment and scientifi c importance of the last continent to be explored. Use the Essential Questions below to connect the exhibition’s themes to your curriculum. What do explorers need to survive during What is Antarctica? Antarctica is Earth’s southernmost continent. About the size of the polar expeditions? United States and Mexico combined, it’s almost entirely covered Exploring Antarc- by a thick ice sheet that gives it the highest average elevation of tica involved great any continent. This ice sheet contains 90% of the world’s land ice, danger and un- which represents 70% of its fresh water. Antarctica is the coldest imaginable physical place on Earth, and an encircling polar ocean current keeps it hardship. Hazards that way. Winds blowing out of the continent’s core can reach included snow over 320 kilometers per hour (200 mph), making it the windiest. blindness, malnu- Since most of Antarctica receives no precipitation at all, it’s also trition, frostbite, the driest place on Earth. Its landforms include high plateaus and crevasses, and active volcanoes. -

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1955-1958

THE COMMONWEALTH TRANS-ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1955-1958 HOW THE CROSSING OF ANTARCTICA MOVED NEW ZEALAND TO RECOGNISE ITS ANTARCTIC HERITAGE AND TAKE AN EQUAL PLACE AMONG ANTARCTIC NATIONS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree PhD - Doctor of Philosophy (Antarctic Studies – History) University of Canterbury Gateway Antarctica Stephen Walter Hicks 2015 Statement of Authority & Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Elements of material covered in Chapter 4 and 5 have been published in: Electronic version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume00,(0), pp.1-12, (2011), Cambridge University Press, 2011. Print version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume 49, Issue 1, pp. 50-61, Cambridge University Press, 2013 Signature of Candidate ________________________________ Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................. -

Thesis Template

Thinking with photographs at the margins of Antarctic exploration A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Canterbury by Kerry McCarthy University of Canterbury 2010 Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................... 2 List of Figures and Tables ............................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................... 6 Abstract ........................................................................................................................... 7 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Thinking with photographs ....................................................................... 10 1.2 The margins ............................................................................................... 14 1.3 Antarctic exploration ................................................................................. 16 1.4 The researcher ........................................................................................... 20 1.5 Overview ................................................................................................... 22 2 An unauthorised genealogy of thinking with photographs .............................. 27 2.1 The -

February 2019 MEET SHAPE CLIENTS COBAN and KRISTIAN

… An Extraordinary Place on a Path to Prosperity Issue 73 February 2019 MEET SHAPE CLIENTS COBAN AND KRISTIAN t Helena Active Participation in Enterprise (SHAPE) aims to promote the rights and wellbeing of people with disabilities in all spheres of society and also to increase awareness. Their training programmes offer opportunities for structured work or supported employment. The focus of their service is Sto enhance employability and to support people with disabilities to achieve their maximum potential. Read the interesting stories of two SHAPE Clients, Coban and Kristian. Coban Scott-John Kristian Green y name is Coban Scott-John and I was born in Stanley on the Falkland Islands in 2001. y name is Kristian Green and I was born on At the age of two I was diagnosed in Ascension Island on 16 February 2001. At Guy’s Hospital in London, UK, as being two weeks old I was flown to the UK and Mautistic. I moved to St Helena at the age of 12 and was diagnosed in the John Radcliffe attended Prince Andrew School. I have been on holidays MHospital, Oxford, as having Down syndrome. I attended to St Helena before and always enjoy my time here. Two Boats School on Ascension until I was 16 years old. I returned to St Helena for good in January 2017. I attend SHAPE twice a week under the Carraresi programme. I am transitioning to SHAPE for when I leave I now attend Prince Andrew School which I really enjoy. I school in September this year. At SHAPE, I engage in a like reading, writing, Art, Maths, English, ICT and I love variety of activities including learning life skills and swimming. -

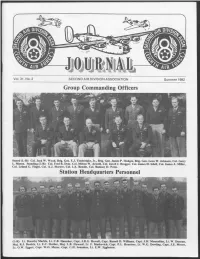

Summer 1992 Group Commanding Officers

Vol. 31, No. 2 SECOND AIR DIVISION ASSOCIATION Summer 1992 Group Commanding Officers Seated (L-R): Col. Jack W. Wood, Brig. Gen. E.J. Timberlake, Jr., Brig. Gen. James P. Hodges, Brig. Gen. Leon W. Johnson, Col. Gerry L. Mason. Standing (L-R): Col. Fred R. Dent, Col. Milton W. Arnold, Col. Jacob J. Brogger, Col. James H. Isbell, Col. James A. Miller, Col. Leland G. Fiegel, Col. A.J. Shower, Col. I.A. Rendle, Col. Ramsay D. Potts. Station Headquarters Personnel (L-R): Lt. Dorothy Marble, Lt. C.B. Hamsher, Capt. J.R.G. Howell, Capt. Russell D. Williams, Capt. J.H. Mouradian, Lt. W. Duncan, Maj. R.J. Bostick, Lt. E.C. Shriber, Maj. L.B. Howard, Lt. F. Markovich, Capt. P.L. Rountree, Lt. W.G. Dowling, Capt. J.E. Moore, Lt. O.W. Eggert, Capt. W.O. Mayer, Capt. C.H. Saunders, Lt. E.W. Eggleston. Second Air Division Association President's Message Eighth Air Force "Musings" HONORARY PRESIDENT by Richard M. Kennedy JORDAN UTTAL 7824 Meadow Park Drive, Apt. 101, Dallas, TX 75230 I continue to register a high level of amazement with OFFICERS respect to the vast amount of "business" that flows across President RICHARD M. KENNEDY my desk as President of the 2nd ADA. While I had a 8051 Goshen Road, Malvern, PA 19355 Executive Vice President JOHN B. CONRAD reasonably solid idea that the 2nd ADA was a viable 2981 Four Pines #1, Lexington, KY 40502 veterans organization, I was considerably off target with Vice President Membership EVELYN COHEN my own estimation of activity from both within and outside Apt. -

We Look for Light Within

“We look for light from within”: Shackleton’s Indomitable Spirit “For scientific discovery, give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel, give me Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when you are seeing no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.” — Raymond Priestley Shackleton—his name defines the “Heroic Age of Antarctica Exploration.” Setting out to be the first to the South Pole and later the first to cross the frozen continent, Ernest Shackleton failed. Sent home early from Robert F. Scott’s Discovery expedition, seven years later turning back less than 100 miles from the South Pole to save his men from certain death, and then in 1914 suffering disaster at the start of the Endurance expedition as his ship was trapped and crushed by ice, he seems an unlikely hero whose deeds would endure to this day. But leadership, courage, wisdom, trust, empathy, and strength define the man. Shackleton’s spirit continues to inspire in the 100th year after the rescue of the Endurance crew from Elephant Island. This exhibit is a learning collaboration between the Rauner Special Collections Library and “Pole to Pole,” an environmental studies course taught by Ross Virginia examining climate change in the polar regions through the lens of history, exploration and science. Fifty-one Dartmouth students shared their research to produce this exhibit exploring Shackleton and the Antarctica of his time. Discovery: Keeping Spirits Afloat In 1901, the first British Antarctic expedition in sixty years commenced aboard the Discovery, a newly-constructed vessel designed specifically for this trip. -

Representations of Antarctic Exploration by Lesser Known Heroic Era Photographers

Filtering ‘ways of seeing’ through their lenses: representations of Antarctic exploration by lesser known Heroic Era photographers. Patricia Margaret Millar B.A. (1972), B.Ed. (Hons) (1999), Ph.D. (Ed.) (2005), B.Ant.Stud. (Hons) (2009) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science – Social Sciences. University of Tasmania 2013 This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. ………………………………….. ………………….. Patricia Margaret Millar Date This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. ………………………………….. ………………….. Patricia Margaret Millar Date ii Abstract Photographers made a major contribution to the recording of the Heroic Era of Antarctic exploration. By far the best known photographers were the professionals, Herbert Ponting and Frank Hurley, hired to photograph British and Australasian expeditions. But a great number of photographs were also taken on Belgian, German, Swedish, French, Norwegian and Japanese expeditions. These were taken by amateurs, sometimes designated official photographers, often scientists recording their research. Apart from a few Pole-reaching images from the Norwegian expedition, these lesser known expedition photographers and their work seldom feature in the scholarly literature on the Heroic Era, but they, too, have their importance. They played a vital role in the growing understanding and advancement of Antarctic science; they provided visual evidence of their nation’s determination to penetrate the polar unknown; and they played a formative role in public perceptions of Antarctic geopolitics.