―Basically a True Story:‖ the Beginning Or the End, Fat Man and Little Boy, and American Remembrance of the Atomic Bomb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

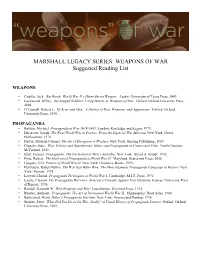

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: WEAPONS of WAR Suggested Reading List

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: WEAPONS OF WAR Suggested Reading List WEAPONS • Couffer, Jack. Bat Bomb: World War II’s Other Secret Weapon. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992. • Lockwood, Jeffrey. Six-Legged Soldiers: Using Insects as Weapons of War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. • O’Connell, Robert L. Of Arms and Men: A History of War, Weapons, and Aggression. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990. PROPAGANDA • Balfour, Michael. Propaganda in War 1939-1945. London: Routledge and Kegan, 1979. • Darracott, Joseph. The First World War in Posters: From the Imperial War Museum. New York: Dover Publications, 1974 • Dewar, Michael Colonel. The Art of Deception in Warfare. New York: Sterling Publishing, 1989. • Dipaolo, Marc. War, Politics and Superheroes: Ethics and Propaganda in Comics and Film. North Carolina: McFarland, 2011. • Ellul, Jacques. Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1965. • Fyne, Robert. The Hollywood Propaganda of World War II. Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2008. • Gregory, G.H. Posters of World War II. New York: Gramercy Books, 1993. • Hertzstein, Robert Edwin. The War that Hitler Won: The Most Infamous Propaganda Campaign in History. New York: Putnam, 1978. • Laswell, Harold. Propaganda Techniques in World War I. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press, 1971. • Laurie, Clayton. The Propaganda Warriors: America’s Crusade Against Nazi Germany. Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1996. • Rendell, Kenneth W. With Weapons and Wits. Lincolnshire: Overlord Press, 1992. • Rhodes, Anthony. Propaganda: The Art of Persuasion World War II. Minneapolis: Book Sales, 1988. • Rutherford, Ward. Hitler’s Propaganda Machine. New York: Grosset and Dunlop, 1978. • Stanley, Peter. What Did You Do in the War, Daddy? A Visual History of Propaganda Posters. -

The Making of an Atomic Bomb

(Image: Courtesy of United States Government, public domain.) INTRODUCTORY ESSAY "DESTROYER OF WORLDS": THE MAKING OF AN ATOMIC BOMB At 5:29 a.m. (MST), the world’s first atomic bomb detonated in the New Mexican desert, releasing a level of destructive power unknown in the existence of humanity. Emitting as much energy as 21,000 tons of TNT and creating a fireball that measured roughly 2,000 feet in diameter, the first successful test of an atomic bomb, known as the Trinity Test, forever changed the history of the world. The road to Trinity may have begun before the start of World War II, but the war brought the creation of atomic weaponry to fruition. The harnessing of atomic energy may have come as a result of World War II, but it also helped bring the conflict to an end. How did humanity come to construct and wield such a devastating weapon? 1 | THE MANHATTAN PROJECT Models of Fat Man and Little Boy on display at the Bradbury Science Museum. (Image: Courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory.) WE WAITED UNTIL THE BLAST HAD PASSED, WALKED OUT OF THE SHELTER AND THEN IT WAS ENTIRELY SOLEMN. WE KNEW THE WORLD WOULD NOT BE THE SAME. A FEW PEOPLE LAUGHED, A FEW PEOPLE CRIED. MOST PEOPLE WERE SILENT. J. ROBERT OPPENHEIMER EARLY NUCLEAR RESEARCH GERMAN DISCOVERY OF FISSION Achieving the monumental goal of splitting the nucleus The 1930s saw further development in the field. Hungarian- of an atom, known as nuclear fission, came through the German physicist Leo Szilard conceived the possibility of self- development of scientific discoveries that stretched over several sustaining nuclear fission reactions, or a nuclear chain reaction, centuries. -

Nathan Reingold Papers, 1947

Nathan Reingold Papers, 1947 Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 1 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Nathan Reingold Papers https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_arc_259150 Collection Overview Repository: Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington, D.C., [email protected] Title: Nathan Reingold Papers Identifier: Accession 05-266 Date: 1947 Extent: 0.43 cu. ft. (0.43 non-standard size boxes) Creator:: Reingold, Nathan, 1927- Language: English Administrative Information Prefered Citation Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-266, Nathan Reingold Papers Descriptive Entry These records consist of motion picture stills and a black-and-white photograph from the Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer movie, The Beginning or the End (1947), directed by Norman Taurog, with original story by Robert Considine and screenplay by Frank W. Wead, and -

Evaluating Agreement and Disagreement Among Movie Reviewers Alan Agresti & Larry Winner Version of Record First Published: 20 Sep 2012

This article was downloaded by: [University of Florida] On: 08 October 2012, At: 16:45 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK CHANCE Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ucha20 Evaluating Agreement and Disagreement among Movie Reviewers Alan Agresti & Larry Winner Version of record first published: 20 Sep 2012. To cite this article: Alan Agresti & Larry Winner (1997): Evaluating Agreement and Disagreement among Movie Reviewers, CHANCE, 10:2, 10-14 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09332480.1997.10542015 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with -

Roger Ebert's

The College of Media at Illinois presents Roger19thAnnual Ebert’s Film Festival2017 April 19-23, 2017 The Virginia Theatre Chaz Ebert: Co-Founder and Producer 203 W. Park, Champaign, IL Nate Kohn: Festival Director 2017 Roger Ebert’s Film Festival The University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign The College of Media at Illinois Presents... Roger Ebert’s Film Festival 2017 April 19–23, 2017 Chaz Ebert, Co-Founder, Producer, and Host Nate Kohn, Festival Director Casey Ludwig, Assistant Director More information about the festival can be found at www.ebertfest.com Mission Founded by the late Roger Ebert, University of Illinois Journalism graduate and a Pulitzer Prize- winning film critic, Roger Ebert’s Film Festival takes place in Urbana-Champaign each April for a week, hosted by Chaz Ebert. The festival presents 12 films representing a cross-section of important cinematic works overlooked by audiences, critics and distributors. The films are screened in the 1,500-seat Virginia Theatre, a restored movie palace built in the 1920s. A portion of the festival’s income goes toward on-going renovations at the theatre. The festival brings together the films’ producers, writers, actors and directors to help showcase their work. A film- maker or scholar introduces each film, and each screening is followed by a substantive on-stage Q&A discussion among filmmakers, critics and the audience. In addition to the screenings, the festival hosts a number of academic panel discussions featuring filmmaker guests, scholars and students. The mission of Roger Ebert’s Film Festival is to praise films, genres and formats that have been overlooked. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Chaz Ebert

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Chaz Ebert Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Ebert, Chaz, 1952- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Chaz Ebert, Dates: August 7, 2017 Bulk Dates: 2017 Physical 5 uncompressed MOV digital video files (2:30:48). Description: Abstract: Lawyer Chaz Ebert (1952 - ) worked as a litigation attorney and served as vice president of the Ebert Company Ltd. Ebert was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on August 7, 2017, in Chicago, Illinois. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2017_121 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Lawyer and entertainment manager Chaz Ebert was born on October 15, 1952 in Chicago, Illinois to Johnnie Hobbs Hammel and Wiley Hammel, Sr. She attended John M. Smyth Elementary School and Crane Technical High School in Chicago, Illinois and graduated in 1969. Ebert earned her B.A. degree in political science at the University of Dubuque in Dubuque, Iowa in 1972. She then received her M.A. degree in social science at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville in Platteville, Wisconsin. Ebert went on to receive her J.D. degree from DePaul University College of Law in Chicago. Ebert began her career in 1977 as a litigator for the Region Five office of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. After three years, she left the agency to join the litigation department at the Chicago law firm of Bell Boyd and Lloyd LLP, where she focused on mergers and acquisitions and intellectual property. -

Scorses by Ebert

Scorsese by Ebert other books by An Illini Century roger ebert A Kiss Is Still a Kiss Two Weeks in the Midday Sun: A Cannes Notebook Behind the Phantom’s Mask Roger Ebert’s Little Movie Glossary Roger Ebert’s Movie Home Companion annually 1986–1993 Roger Ebert’s Video Companion annually 1994–1998 Roger Ebert’s Movie Yearbook annually 1999– Questions for the Movie Answer Man Roger Ebert’s Book of Film: An Anthology Ebert’s Bigger Little Movie Glossary I Hated, Hated, Hated This Movie The Great Movies The Great Movies II Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert Your Movie Sucks Roger Ebert’s Four-Star Reviews 1967–2007 With Daniel Curley The Perfect London Walk With Gene Siskel The Future of the Movies: Interviews with Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas DVD Commentary Tracks Beyond the Valley of the Dolls Casablanca Citizen Kane Crumb Dark City Floating Weeds Roger Ebert Scorsese by Ebert foreword by Martin Scorsese the university of chicago press Chicago and London Roger Ebert is the Pulitzer The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 Prize–winning film critic of the Chicago The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London Sun-Times. Starting in 1975, he cohosted © 2008 by The Ebert Company, Ltd. a long-running weekly movie-review Foreword © 2008 by The University of Chicago Press program on television, first with Gene All rights reserved. Published 2008 Siskel and then with Richard Roeper. He Printed in the United States of America is the author of numerous books on film, including The Great Movies, The Great 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 Movies II, and Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert, the last published by the ISBN-13: 978-0-226-18202-5 (cloth) University of Chicago Press. -

Chapter 1 Chapter 2

Notes Chapter 1 1. Jeffrey Mirel, “The Traditional High School: Historical Debates over Its Nature and Function,” Education Next 6 (2006): 14–21. 2. US Census Bureau, “Education Summary––High School Gradu- ates, and College Enrollment and Degrees: 1900 to 2001,” His- torical Statistics Table HS-21, http://www.census.gov/statab/ hist/HS-21.pdf. 3. Andrew Monument, dir., Nightmares in Red, White, and Blue: The Evolution of American Horror Film (Lux Digital Pictures, 2009). 4. Monument, Nightmares in Red. Chapter 2 1. David J. Skal, Screams of Reason: Mad Science and Modern Cul- ture (New York: Norton, 1998), 18–19. For a discussion of this more complex image of the mad scientist within the context of postwar film science fiction comedies, see also Sevan Terzian and Andrew Grunzke, “Scrambled Eggheads: Ambivalent Represen- tations of Scientists in Six Hollywood Film Comedies from 1961 to 1965,” Public Understanding of Science 16 (October 2007): 407–419. 2. Esther Schor, “Frankenstein and Film,” in The Cambridge Com- panion to Mary Shelley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 63; James A. W. Heffernan, “Looking at the Monster: Frankenstein and Film,” Critical Inquiry 24, no. 1 (Autumn 1997): 136. 3. Russell Jacoby, The Last Intellectuals: American Culture in the Age of Academe (New York: Basic Books, 1987). 4. Richard Hofstadter, Anti-Intellectualism and American Life (New York: Knopf, 1963); Craig Howley, Aimee Howley, and Edwine D. Pendarvis, Out of Our Minds: Anti-Intellectualism and Talent 178 Notes Development in American Schooling (New York: Teachers Col- lege Press: 1995); Merle Curti, “Intellectuals and Other People,” American Historical Review 60 (1955): 259–282. -

Un Dioparama Du Regroupement Pour La Surveillance Du Nucléaire

l’Uranium un dioparama du Regroupement pour la surveillance du nucléaire (Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility) presenté par Gordon Edwards, Ph.D., président du RSN, aux commissaires du BAPE, le 17 novembre, 2014 Regroupement pour la surveillance du nucléaire www.ccnr.org/index_f.html PART 1 Uses for Uranium 1. Nuclear Weapons 2. Fuel for Nuclear Reactors A Model of the Every atom has a Uranium Atom tiny “nucleus” at the centre, with electrons in orbit around it. Uranium is special. It is the key element behind all nuclear technology, whether military or civilian. Photo: Robert Del Tredici A Monument to the Splitting of the Atom Splitting of the Atom When the uranium nucleus is “split” enormous energy is released. And the broken pieces of uranium atoms are extremely radioactive. iPhoto: Robert Del Tredici Canadian Uranium for Bombs 1941-1965 The Quebec Accord CANADA – USA - UK Prime Quebec City President Prime Minister 1943 of the U.S.A. Minister of Canada of Britain Quebec Agreement Uranium from Canada to be used in WWII Atomic Bomb Project Fat Man – made from plutonium (a uranium derivative) Fat Man and Little Boy Little Boy – made from Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU) Models of the two Atomic Bombs dropped on Japan in 1945 iPhoto: Robert Del Tredici Destruction of the City of Hiroshima caused by Little Boy, August 6, 1945 The Yellowcake Road (Canada) Yellowcake Road All uranium goes to Port Hope on Lake Ontario for Map by G. Edwards conversion to uranium hexafluoride or uranium dioxide & Robert Del Tredici Uses of Uranium UnGl 1945, all Canadian uranium was sold to the US military for Bombs. -

April 2018 Vol

News We’re All a Part Of . April 2018 Vol. 7 Issue 6 Observer Contents 2 Vol. 7 Issue 6 April 2018 Cover Design: Joshua Mission & Vision Carstens & Dekanuva News We’re All a 3. Announcements Part Of 4. Titanic Panic Dear Readers, It is our mission as the Alfred-Almond Observer to provide truthful, 6. Cherry Blossoms Welcome to the sixth unbiased, and accurate edition of The Observer! information to the student 7. Different, Not Less body. Our goal is to In this edition we’ll cover deliver relevant stories 8. March for Our Lives how the Alfred-Almond focused on both informing and entertaining the alumni are handling Alfred-Almond community. 10. School Safety We strive to promote a college, and how the positive school climate 12. Youth Summit track team is ready to and will use the Observer spring into action. Did as a way to give all voices 14. Who is it? at Alfred-Almond a platform. you miss the March For 16. Alumni Answers Our Lives event? No Observer Staff: worries, we have it 19. Track Previews covered! Having trouble DJ Don and the Bees: Duncan B-C: DJ Don; Public 21. Spring Break trying to figure out what Relation Manager to do over spring break? Josh C. : Bee 2.253; Design Bee 23. Coachella Attilo C. : Bee 6; Worker Bee We have some options! Jessie M. : Queen Bee/ Editor-in-Chief 25. Amazing eBay and Want to see the peculiar Sophie N. : Bee Numba 5; Writer Amazon Products Bee things you can buy on Maya R. -

Fall 2009 Riding, Eating and Raising Money for Good Causes

Analyze This Not Just Bricks Winning Words 14 17 and Mortar 20 I have a wonderful life and I am forever grateful for that, so I give back. Maybe I can help somebody else along the way. After putting her children through college, Connie Kihm ’95 decided it was her turn to earn a bachelor’s degree. She had had a successful career as a retail buyer, but still wanted “that piece of paper.” At the age of 48, she started her degree at Towson “University, and has wanted to give back ever since. “I give back to the school that has given me so much. Nothing in life is free. If you have been blessed, I believe you need to give,” Kihm says. Amid difficult economic times and declining state support, Kihm realizes how important it is to give to the Towson Fund, TU’s campaign for annual operating support that ” provides students and faculty with vital funding. Most recently, in addition to her annual gift, Kihm focused her support on the new College of Liberal Arts building. As an English major, Kihm was excited to help her alma mater with its beautiful addition. “My husband, Jim, and I donated a classroom in honor of emeritus Professor George Friedman, who inspired me as a student. Although Jim is not a TU graduate he’s a big supporter because of how happy the university made me. His company matches whatever I give,“ she says. Join Connie and the many others whose lives have been touched by their experiences at Towson University. -

APUSH) SUMMER ASSIGNMENT 2014/2015 Ms

AP US HISTORY (APUSH) SUMMER ASSIGNMENT 2014/2015 Ms. Young [email protected] SUGGESTED READINGS *Remember you really should read one of these books in addition to Founding Brothers. You will thank me later! The Killer Angels – by Michael Shaara Undaunted Courage – by Stephen Ambrose Confederates in the Attic – by Tony Horwitz Andrew Jackson, His Life and Times – by H. W. Brands 1776 – by David McCulloch Seabiscuit: An American Legend- Laura Hillenbrand Water for elephants – by Sara Gruen Under the Banner of Heaven – John Krakauer March – by Geraldine Brooks The Help – by Kathryn Stockett Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy – by Jules Tygiel Somebody Knows My Name – by Lawrence Hill The Last Boy: Mickey Mantle and the End of America’s Childhood – by Jane Leavy Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption by Laura Hillendbrand Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee – Dee Brown Founding Mothers – by Cokie Roberts Team of Rivals – by Doris Kearns Goodwin Lies My Teacher Told Me – by James W. Loewen Narrative of the Life of Frederick Dougalss – by Frederick Douglass The Greatest Generation – by Tom Brokaw Devil in the White City – by Erik Larson In the Garden of Beasts – by Erik Larson The Rape of Nanking – by Iris change Triangle: the Tire that Changed America – by David von Drehle We Were Soldiers Once…and Young – by Harold G. Moore and Joseph L. Galloway A Rumor of War – by Philip Caputo Lonesome Dove – by Larry McMurtry At the Hands of Persons Unknown – Phillip Dray Fire in a Canebrake: The Last Mass Lynching in America – Laura Wexler SUGGESTED MOVIES *The movies are divided by historical eras.