Writing the Nation: a Concise Introduction to American Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Realism.VL.2.Pdf

Realism Realism 1861- 1914: An artistic movement begun in 19th century France. Artists and writers strove for detailed realistic and factual description. They tried to represent events and social conditions as they actually are, without idealization. This form of literature believes in fidelity to actuality in its representation. Realism is about recreating life in literature. Realism arose as an opposing idea to Idealism and Nominalism. Idealism is the approach to literature of writing about everything in its ideal from. Nominalism believes that ideas are only names and have no practical application. Realism focused on the truthful treatment of the common, average, everyday life. Realism focuses on the immediate, the here and now, the specific actions and their verifiable consequences. Realism seeks a one-to-one relationship between representation and the subject. This form is also known as mimesis. Realists are concerned with the effect of the work on their reader and the reader's life, a pragmatic view. Pragmatism requires the reading of a work to have some verifiable outcome for the reader that will lead to a better life for the reader. This lends an ethical tendency to Realism while focusing on common actions and minor catastrophes of middle class society. Realism aims to interpret the actualities of any aspect of life, free from subjective prejudice, idealism, or romantic color. It is in direct opposition to concerns of the unusual, the basis of Romanticism. Stresses the real over the fantastic. Seeks to treat the commonplace truthfully and used characters from everyday life. This emphasis was brought on by societal changes such as the aftermath of the Civil War in the United States and the emergence of Darwin's Theory of Evolution and its effect upon biblical interpretation. -

Kathy Sledge Press

Web Sites Website: www.kathysledge.com Website: http: www.brightersideofday.com Social Media Outlets Facebook: www.facebook.com/pages/Kathy-Sledge/134363149719 Twitter: www.twitter.com/KathySledge Contact Info Theo London, Management Team Email: [email protected] Kathy Sledge is a Renaissance woman — a singer, songwriter, author, producer, manager, and Grammy-nominated music icon whose boundless creativity and passion has garnered praise from critics and a legion of fans from all over the world. Her artistic triumphs encompass chart-topping hits, platinum albums, and successful forays into several genres of popular music. Through her multi-faceted solo career and her legacy as an original vocalist in the group Sister Sledge, which included her lead vocals on worldwide anthems like "We Are Family" and "He's the Greatest Dancer," she's inspired millions of listeners across all generations. Kathy is currently traversing new terrain with her critically acclaimed show The Brighter Side of Day: A Tribute to Billie Holiday plus studio projects that span elements of R&B, rock, and EDM. Indeed, Kathy's reached a fascinating juncture in her journey. That journey began in Philadelphia. The youngest of five daughters born to Edwin and Florez Sledge, Kathy possessed a prodigious musical talent. Her grandmother was an opera singer who taught her harmonies while her father was one-half of Fred & Sledge, the tapping duo who broke racial barriers on Broadway. "I learned the art of music from my father and my grandmother. The business part of music was instilled through my mother," she says. Schooled on an eclectic array of artists like Nancy Wilson and Mongo Santamaría, Kathy and her sisters honed their act around Philadelphia and signed a recording contract with Atco Records. -

A History of American Civil War Literature Edited by Coleman Hutchison Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-10972-8 - A History of American Civil War Literature Edited by Coleman Hutchison Frontmatter More information A HISTORY OF AMERICAN CIVIL WAR LITERATURE Th is book is the fi rst omnibus history of the literature of the American Civil War, the deadliest confl ict in U.S. history. A History of American Civil War Literature examines the way the war has been remembered and rewritten over time. Th is history incorporates new directions in Civil War historiography and cultural studies while giving equal attention to writings from both the northern and the southern states. Written by leading scholars in the fi eld, this book works to redefi ne the boundaries of American Civil War literature while posing a fundamental question: Why does this 150-year-old confl ict continue to capture the American imagination? Coleman Hutchison is an associate professor of English at Th e University of Texas at Austin, where he teaches courses in nineteenth-century U.S. literature and culture, bibliography and tex- tual studies, and poetry and poetics. He is the author of the fi rst literary history of the Civil War South, Apples and Ashes: Literature, Nationalism, and the Confederate States of America (2012) and the coauthor of Writing about American Literature: A Guide for Students (2014). Hutchison’s work has appeared in American Literary History, Common-Place, Comparative American Studies, CR: Th e New Centennial Review, Journal of American Studies, Th e Emily Dickinson Journal, PMLA , and Southern Spaces, among other venues. -

Native American Literature: Remembrance, Renewal

U.S. Society and Values, "Contemporary U.S. Literature: Multicultura...partment of State, International Information Programs, February 2000 NATIVE AMERICAN LITERATURE: REMEMBRANCE, RENEWAL By Geary Hobson In 1969, the fiction committee for the prestigious Pulitzer Prizes in literature awarded its annual honor to N. Scott Momaday, a young professor of English at Stanford University in California, for a book entitled House Made of Dawn. The fact that Momaday's novel dealt almost entirely with Native Americans did not escape the attention of the news media or of readers and scholars of contemporary literature. Neither did the author's Kiowa Indian background. As news articles pointed out, not since Oliver LaFarge received the same honor for Laughing Boy, exactly 40 years earlier, had a so-called "Indian" novel been so honored. But whereas LaFarge was a white man writing about Indians, Momaday was an Indian -- the first Native American Pulitzer laureate. That same year, 1969, another young writer, a Sioux attorney named Vine Deloria, Jr., published Custer Died For Your Sins, subtitled "an Indian Manifesto." It examined, incisively, U.S. attitudes at the time towards Native American matters, and appeared almost simultaneously with The American Indian Speaks, an anthology of writings by various promising young American Indians -- among them Simon J. Ortiz, James Welch, Phil George, Janet Campbell and Grey Cohoe, all of whom had been only fitfully published at that point. These developments that spurred renewed -- or new -- interest in contemporary Native American writing were accompanied by the appearance around that time of two works of general scholarship on the subject, Peter Farb's Man's Rise to Civilization (1968) and Dee Brown's Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee (1970). -

Accepted Draft

ACCEPTED DRAFT Title: ‘Bad Retail’: A romantic fiction Author: Laurence Figgis Output Type: Article Published: Journal of Writing in Creative Practice Date: 2017 Biography Laurence Figgis is an artist and writer and a lecturer in Fine Art (Painting and Printmaking) at the Glasgow School of Art. He works in collage, painting, drawing, fiction and poetry. His recent exhibitions include (After) After at Leeds College of Art (2017), Human Shaped at Sculpture & Design, Glasgow (for Glasgow International 2016) and Oh My Have at 1 Royal Terrace, Glasgow (2015). He has produced commissioned texts for other artists’ exhibitions and catalogues including for Lorna Macintyre, Zoe Williams and Cathy Wilkes. His live-performance work ‘Even or Perhaps’ (at DCA, Dundee, 2014) was programmed as part of Generation, a nationwide celebration of Scottish contemporary art. [email protected] www.laurencefiggis.co.uk Abstract ‘Bad Retail’ is a work of fiction that I wrote to accompany a series of my own narrative paintings. The text was originally disseminated through a series of exhibitions in the form of printed handouts that were included alongside the visual works. The story evolved from a simultaneous investigation of two related devices in literature and painting: anachronism and collage. These 1 ACCEPTED DRAFT terms are linked by an act of displacement: of objects from history and of images from their source. This compositional tendency is characteristic of late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth- century romantic fiction, which often refuses to conform to (and remain within) accustomed genre categories. The aforementioned narrative will be accompanied here by a series of illustrations based on the paintings and drawings that I produced in tandem with the text. -

In the Last Year Or So, Scholarship in American Literature Has Been

REVIEWS In the last year or so, scholarship in American Literature has been extended by the appearance of three exciting series which reassess, synthesize, and clarify the work and reputation of major American writers and literary groups. MASAJ begins with this issue reviews of representative titles in Twayne's United States Authors Series (Sylvia Bowman, Indiana University, General Editor); Barnes & Noble's American Authors and Critics Series (Foster Provost and John Mahoney, Duquesne University, General Editors); and The University of Minnesota Pamphlets on American Writers (William Van O'Connor, Allen Tate, Leonard Unger, and Robert Penn Warren, Editors), and will continue such reviews until the various series are completed. Twayne's United States Authors Series (TUSAS), (Hardback Editions) JOHN GREENLEAF WHITTIER. By Lewis Leary. New York: Twayne Pub lishers, Inc. 1961. $3.50. As a long overdue reappraisal, this book places Whittier squarely within the cultural context_of his age and then sympathetically, but objectively, ana lyzes his poetic achievement. Leary * s easy style and skillful use of quotations freshen the well-known facts of Whittier's life. Unlike previous biographers he never loses sight of the poet while considering Whittier's varied career as editor, politician and abolitionist. One whole chapter, "The Beauty of Holi ness ," presents Whittier1 s artistic beliefs and stands as one of the few extended treatments of his aesthetics in this century. Also Leary is not afraid to measure Whittier Ts limitations against major poets like Whitman and Emerson, and this approach does much to highlight Whittier's poetic successes. How ever, the book's real contribution is its illuminating examination of Whittier's artistry: the intricate expansion of theme by structure in "Snow-Bound," the tensions created by subtle Biblical references in "Ichabod, " and the graphic blending of legend and New England background in "Skipper Ireson's Ride." Even long forgotten poems like "The Cypress-Tree of Ceylon" reveal surprising poetic qualities. -

Disco Top 15 Histories

10. Billboard’s Disco Top 15, Oct 1974- Jul 1981 Recording, Act, Chart Debut Date Disco Top 15 Chart History Peak R&B, Pop Action Satisfaction, Melody Stewart, 11/15/80 14-14-9-9-9-9-10-10 x, x African Symphony, Van McCoy, 12/14/74 15-15-12-13-14 x, x After Dark, Pattie Brooks, 4/29/78 15-6-4-2-2-1-1-1-1-1-1-2-3-3-5-5-5-10-13 x, x Ai No Corrida, Quincy Jones, 3/14/81 15-9-8-7-7-7-5-3-3-3-3-8-10 10,28 Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us, McFadden & Whitehead, 5/5/79 14-12-11-10-10-10-10 1,13 Ain’t That Enough For You, JDavisMonsterOrch, 9/2/78 13-11-7-5-4-4-7-9-13 x,89 All American Girls, Sister Sledge, 2/21/81 14-9-8-6-6-10-11 3,79 All Night Thing, Invisible Man’s Band, 3/1/80 15-14-13-12-10-10 9,45 Always There, Side Effect, 6/10/76 15-14-12-13 56,x And The Beat Goes On, Whispers, 1/12/80 13-2-2-2-1-1-2-3-3-4-11-15 1,19 And You Call That Love, Vernon Burch, 2/22/75 15-14-13-13-12-8-7-9-12 x,x Another One Bites The Dust, Queen, 8/16/80 6-6-3-3-2-2-2-3-7-12 2,1 Another Star, Stevie Wonder, 10/23/76 13-13-12-6-5-3-2-3-3-3-5-8 18,32 Are You Ready For This, The Brothers, 4/26/75 15-14-13-15 x,x Ask Me, Ecstasy,Passion,Pain, 10/26/74 2-4-2-6-9-8-9-7-9-13post peak 19,52 At Midnight, T-Connection, 1/6/79 10-8-7-3-3-8-6-8-14 32,56 Baby Face, Wing & A Prayer, 11/6/75 13-5-2-2-1-3-2-4-6-9-14 32,14 Back Together Again, R Flack & D Hathaway, 4/12/80 15-11-9-6-6-6-7-8-15 18,56 Bad Girls, Donna Summer, 5/5/79 2-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-2-2-3-10-13 1,1 Bad Luck, H Melvin, 2/15/75 12-4-2-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-2-2-3-4-5-5-7-10-15 4,15 Bang A Gong, Witch Queen, 3/10/79 12-11-9-8-15 -

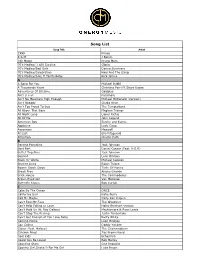

2020 C'nergy Band Song List

Song List Song Title Artist 1999 Prince 6:A.M. J Balvin 24k Magic Bruno Mars 70's Medley/ I Will Survive Gloria 70's Medley/Bad Girls Donna Summers 70's Medley/Celebration Kool And The Gang 70's Medley/Give It To Me Baby Rick James A A Song For You Michael Bublé A Thousands Years Christina Perri Ft Steve Kazee Adventures Of Lifetime Coldplay Ain't It Fun Paramore Ain't No Mountain High Enough Michael McDonald (Version) Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan Ain't Too Proud To Beg The Temptations All About That Bass Meghan Trainor All Night Long Lionel Richie All Of Me John Legend American Boy Estelle and Kanye Applause Lady Gaga Ascension Maxwell At Last Ella Fitzgerald Attention Charlie Puth B Banana Pancakes Jack Johnson Best Part Daniel Caesar (Feat. H.E.R) Bettet Together Jack Johnson Beyond Leon Bridges Black Or White Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Boogie Oogie Oogie Taste Of Honey Break Free Ariana Grande Brick House The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl Van Morisson Butterfly Kisses Bob Carisle C Cake By The Ocean DNCE California Gurl Katie Perry Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jespen Can't Feel My Face The Weekend Can't Help Falling In Love Haley Reinhart Version Can't Hold Us (ft. Ray Dalton) Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Can't Get Enough of You Love Babe Barry White Coming Home Leon Bridges Con Calma Daddy Yankee Closer (feat. Halsey) The Chainsmokers Chicken Fried Zac Brown Band Cool Kids Echosmith Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Counting Stars One Republic Country Girl Shake It For Me Girl Luke Bryan Crazy in Love Beyoncé Crazy Love Van Morisson D Daddy's Angel T Carter Music Dancing In The Street Martha Reeves And The Vandellas Dancing Queen ABBA Danza Kuduro Don Omar Dark Horse Katy Perry Despasito Luis Fonsi Feat. -

The All American Boy

The All American Boy His teeth I remember most about him. An absolutely perfect set kept totally visible through the mobile shutter of a mouth that rarely closed as he chewed gum and talked, simultaneously. A tricky manoeuvre which demanded great facial mobility. He was in every way the epitome of what the movies, and early TV had taught me to think of as the “All American Boy”. Six foot something, crew cut hair, big beaming smile, looked to be barely twenty. His mother must have been very proud of him! I was helping him to refuel the Neptune P2V on the plateau above Wilkes from numerous 44 gallon drums of ATK we had hauled to the “airstrip” on the Athey waggon behind a D4 driven by Max Berrigan. I think he was an aircraft mechanic. He and eight of his compatriots had just landed after a flight from Mirny, final stop McMurdo. Somehow almost all of the rest of his crew, and ours, had hopped into the weasels to go back to base for a party, leaving just a few of us “volunteers” to refuel. I remember too, feeling more than a little miffed when one of the first things he said after our self- introductions was “That was one hell of a rough landing strip you guys have - nearly as bad as Mirny”. Poor old Max had ploughed up and down with the D4 for hours knocking the tops of the Sastrugi and giving the “strip” as smooth a surface as he could. For there was not really a strip at Wilkes just a slightly flatter area of plateau defined by survey pegs. -

The RAND American Life Panel

LABOR AND POPULATION The RAND American Life Panel Technical Description Michael Pollard, Matthew D. Baird For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1651 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This report describes the methodology behind the RAND American Life Panel. This research was undertaken within RAND Labor and Population. RAND Labor and Population has built an international reputation for conducting objective, high-quality, empirical research to support and improve policies and organizations around the world. Its work focuses on chil- dren and families, demographic behavior, education and training, labor markets, social welfare policy, immigration, international development, financial decisionmaking, and issues related to aging and retirement, with a common aim of understanding how policy and social and eco- nomic forces affect individual decisionmaking and human well-being. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

I PRACTICAL MAGIC: MAGICAL REALISM and the POSSIBILITIES

i PRACTICAL MAGIC: MAGICAL REALISM AND THE POSSIBILITIES OF REPRESENTATION IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY FICTION AND FILM by RACHAEL MARIBOHO DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2016 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Wendy B. Faris, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Kenneth Roemer Johanna Smith ii ABSTRACT: Practical Magic: Magical Realism And The Possibilities of Representation In Twenty-First Century Fiction And Film Rachael Mariboho, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2016 Supervising Professor: Wendy B. Faris Reflecting the paradoxical nature of its title, magical realism is a complicated term to define and to apply to works of art. Some writers and critics argue that classifying texts as magical realism essentializes and exoticizes works by marginalized authors from the latter part of the twentieth-century, particularly Latin American and postcolonial writers, while others consider magical realism to be nothing more than a marketing label used by publishers. These criticisms along with conflicting definitions of the term have made classifying contemporary works that employ techniques of magical realism a challenge. My dissertation counters these criticisms by elucidating the value of magical realism as a narrative mode in the twenty-first century and underlining how magical realism has become an appealing means for representing contemporary anxieties in popular culture. To this end, I analyze how the characteristics of magical realism are used in a select group of novels and films in order to demonstrate the continued significance of the genre in modern art. I compare works from Tea Obreht and Haruki Murakami, examine the depiction of adolescent females in young adult literature, and discuss the environmental and apocalyptic anxieties portrayed in the films Beasts of the Southern Wild, Take iii Shelter, and Melancholia.