Imperial Air Routes: Discussion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Is a Pre-Copyedited, Author-Produced Version of an Article Accepted for Publication in Twentieth Century British History Following Peer Review

1 This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Twentieth Century British History following peer review. The version of record, Brett Holman, ‘The shadow of the airliner: commercial bombers and the rhetorical destruction of Britain, 1917-35’, Twentieth Century British History 24 (2013), 495-517, is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/tcbh/hws042. The shadow of the airliner: commercial bombers and the rhetorical destruction of Britain, 1917-19351 Brett Holman, Independent Scholar Aerial bombardment was widely believed to pose an existential threat to Britain in the 1920s and 1930s. An important but neglected reason for this was the danger from civilian airliners converted into makeshift bombers, the so-called ‘commercial bomber’: an idea which arose in Britain late in the First World War. If true, this meant that even a disarmed Germany 1 The author would like to thank: the referees, for their detailed comments; Chris A. Williams, for his assistance in locating a copy of Cd. 9218; and, for their comments on a draft version of this article, Alan Allport, Christopher Amano- Langtree, Corry Arnold, Katrina Gulliver, Wilko Hardenberg, Lester Hawksby, James Kightly, Beverley Laing, Ross Mahoney, Andre Mayer, Bob Meade, Andrew Reid, and Alun Salt. Figure 1 first appeared in the Journal of the Royal Institute of International Affairs, Vol, 8, No. 4, July 1929, pp, 289-317, and is reproduced with permission. 2 could potentially attack Britain with a large bomber force thanks to its successful civil aviation industry. By the early 1930s the commercial bomber concept appeared widely in British airpower discourse. -

Case 1: Sir Frederick Sykes the First Display in the Gallery Contains

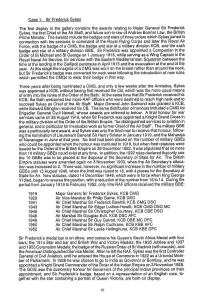

Case 1: Sir Frederick Sykes The first display in the gallery contains the awards relating to Major General Sir Frederick Sykes, the first Chief of the Air Staff, and future son-in-law of Andrew Bonnar Law, the British Prime Minister. The awards include the badges and stars of three orders which Sykes joined in connection with his services in command of the Royal Flying Corps and later the Royal Air Force, with the badge of a CMG, the badge and star of a military division KCB, and the sash badge and star of a military division GBE. Sir Frederick was appointed a Companion in the Order of St Michael and St George on 1 January 1916, while serving as a Wing Captain in the Royal Naval Air Service, for services with the Eastern Mediterranean Squadron between the time of the landing in the Gallipoli peninsula in April 1915 and the evacuation at the end of the year. At this stage the insignia of a CMG was worn on the breast rather than around the neck, but Sir Frederick’s badge was converted for neck wear following the introduction of new rules which permitted the CMGs to wear their badge in that way. Three years after being nominated a CMG, and only a few weeks after the Armistice, Sykes was appointed a KCB, without having first received the CB, which was the more usual means of entry into the ranks of the Order of the Bath. At the same time that Sir Frederick received his KCB, the Bath welcomed two more RAF officers who were destined to reach high rank and to succeed Sykes as Chief of the Air Staff: Major General John Salmond was granted a KCB, while Edward Ellington received his CB. -

Ii. Ausgangslage 1. Die Royal Air Force Am Ende Des Ersten Weltkriegs

II. AUSGANGSLAGE 1. DIE ROYAL AIR FORCE AM ENDE DES ERSTEN WELTKRIEGS 1.1 DER ERSTE WELTKRIEG Die Entwicklung des militärischen Flugwesens Im Verlauf der voranschreitenden Entwicklungen in der zivilen Luftfahrt wur- de die seit dem Jahr 1888 bestehende School of Ballooning am 1. April 1911 in ein Air Battalion als Teil der Royal Engineers reorganisiert. Diese Einheit, bestehend aus etwa 150 Mann, verwendete erstmals motorgetriebene Flugma- schinen für militärische Zwecke. Ihr erster Kommandeur war Major Sir Alex- ander Bannerman, dem ein Jahr darauf Major Frederick Sykes nachfolgte. Sykes war ein Befürworter des Einsatzes von Flugzeugen zu Aufklärungszwe- cken. Im gleichen Jahr wurde er vom Committee of Imperial Defence1 (CID) mit einer Untersuchung des Nutzens von Flugzeugen im Krieg betraut.2 Das War Office schickte den damaligen Captain nach Frankreich, wo er als Manö- verbeobachter den Wert von Flugzeugen bei militärischen Operationen beur- teilen sollte. Er war davon überzeugt, dass Flugzeuge künftig eine entschei- dende Rolle in der Kriegführung spielen würden und bereitete sich auch privat darauf vor. Sykes erlernte das Fliegen und belegte einen Kurs über Aerodyna- mik an der London University. Entsprechend positiv fiel sein Bericht nach den französischen Manövern aus. Er resümierte, dass ein Flugzeug Aufklärungs- ergebnisse in vier Stunden liefern konnte, wo eine Patrouille zu Pferd vier Tage benötigen würde: „There can no longer be any doubt as to the value of aero- planes in locating an enemy on land and obtaining information.“3 Der Bericht veranlasste die Entscheidungsträger zur Formierung eines Naval Wing, eines Military Wing, einer Central Flying School und einer Aircraft Factory.4 Zu- 1 Vom Beginn des 20. -

British Identity, the Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2019 A Return to Camelot?: British Identity, The Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image Abby S. Whitlock College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Whitlock, Abby S., "A Return to Camelot?: British Identity, The Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image" (2019). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1276. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1276 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Return to Camelot?: British Identity, The Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image Abby Stapleton Whitlock Undergraduate Honors Thesis College of William and Mary Lyon G. Tyler Department of History 24 April 2019 Whitlock !2 Whitlock !3 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………….. 4 Introduction …………………………………….………………………………… 5 Chapter I: British Aviation and the Future of War: The Emergence of the Royal Flying Corps …………………………………….……………………………….. 13 Wartime Developments: Organization, Training, and Duties Uniting the Air Services: Wartime Exigencies and the Formation of the Royal Air Force Chapter II: The Cultural Image of the Royal Flying Corps .……….………… 25 Early Roots of the RFC Image: Public Imagination and Pre-War Attraction to Aviation Marketing the “Cult of the Air Fighter”: The Dissemination of the RFC Image in Government Sponsored Media Why the Fighter Pilot? Media Perceptions and Portrayals of the Fighter Ace Chapter III: Shaping the Ideal: The Early Years of Aviation Psychology .…. -

View of the British Way in Warfare, by Captain B

“The Bomber Will Always Get Through”: The Evolution of British Air Policy and Doctrine, 1914-1940 A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Katie Lynn Brown August 2011 © 2011 Katie Lynn Brown. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled “The Bomber Will Always Get Through”: The Evolution of British Air Policy and Doctrine, 1914-1940 by KATIE LYNN BROWN has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Peter John Brobst Associate Professor of History Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT BROWN, KATIE LYNN, M.A., August 2011, History “The Bomber Will Always Get Through”: The Evolution of British Air Policy and Doctrine, 1914-1940 Director of Thesis: Peter John Brobst The historiography of British grand strategy in the interwar years overlooks the importance air power had in determining Britain’s interwar strategy. Rather than acknowledging the newly developed third dimension of warfare, most historians attempt to place air power in the traditional debate between a Continental commitment and a strong navy. By examining the development of the Royal Air Force in the interwar years, this thesis will show that air power was extremely influential in developing Britain’s grand strategy. Moreover, this thesis will study the Royal Air Force’s reliance on strategic bombing to consider any legal or moral issues. Finally, this thesis will explore British air defenses in the 1930s as well as the first major air battle in World War II, the Battle of Britain, to see if the Royal Air Force’s almost uncompromising faith in strategic bombing was warranted. -

By the Seat of Their Pants

BY THE SEAT OF THEIR PANTS THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE HELD AT THE RAAF MUSEUM , POINT COOK BY MILITARY HISTORY AND HERITAGE VICTORIA 12 NOVEMBER 2012 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AAC Australian Air Corps AFC Australian Flying Corps AIF Australian Imperial Force AWM Australian War Memorial CFS Central Flying School DFC Distinguished Flying Cross DSO Distinguished Service Order KIA Killed in Action MC Military Cross MM Military Medal NAA National Archives of Australia NAUK The National Archives of the UK NCO Non-Commissioned Officer POW Prisoner of War RAAF Royal Australian Air Force RFC Royal Flying Corps RNAS Royal Naval Air Service SLNSW State Library of New South Wales NOTES ON CONTRIBUTOR MR MICHAEL MOLKENTIN Michael is a PhD candidate at the University of New South Wales where he is writing a thesis titled ‘Australia, the Empire and the Great War in the Air’. His research will form the basis of a volume in the Australian Army’s Centenary History of the Great War series that Oxford University Press will publish in 2014. Michael is a qualified history teacher and battlefield tour guide and has worked as a consultant for programs screened on the ABC and Chanel 9. Michael has contributed articles to the Journal of the Australian War Memorial , Teaching History , Wartime , Cross & Cockade , Over the Front and Flightpath , and is the author of two books: Fire in the Sky: The Australian Flying Corps in the First World War (Allen & Unwin, 2010) and Flying the Southern Cross: Aviators Charles Ulm and Charles Kingsford Smith (National Library of Australia, 2012). -

THE BRITISH AIR CAMPAIGN DURING the BATTLE of the SOMME APRIL-NOVEMBER, 1916: a PYRRHIC VICTORY by Thomas G. Bradbeer M.A., Univ

THE BRITISH AIR CAMPAIGN DURING THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME APRIL-NOVEMBER, 1916: A PYRRHIC VICTORY By Thomas G. Bradbeer M.A., University of Saint Mary, 1999 Submitted to the graduate degree program in History and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________ Chairperson Theodore A. Wilson, PhD Committee members ____________________ Jonathan H. Earle, PhD ____________________ Adrian R. Lewis, PhD ____________________ Brent J. Steele, PhD ____________________ Jacob Kipp, PhD Date defended: March 28, 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Thomas G. Bradbeer certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE BRITISH AIR CAMPAIGN DURING THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME APRIL-NOVEMBER, 1916: A PYRRHIC VICTORY ___________________ Chairperson Theodore A. Wilson, PhD Date approved March 28, 2011 ii THE BRITISH AIR CAMPAIGN DURING THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME, APRIL-NOVEMBER, 1916: A PYRRHIC VICTORY ABSTRACT The Battle of the Somme was Britain’s first major offensive of the First World War. Just about every facet of the campaign has been analyzed and reexamined. However, one area of the battle that has been little explored is the second battle which took place simultaneously to the one on the ground. This second battle occurred in the skies above the Somme, where for the first time in the history of warfare a deliberate air campaign was planned and executed to support ground operations. The British Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was tasked with achieving air superiority over the Somme sector before the British Fourth Army attacked to start the ground offensive. -

Trenchard's Doctrine: Organisational Culture, the 'Air Force Spirit' and The

TRENCHARD’S DOCTRINE Trenchard’s Doctrine: Organisational Culture, the ‘Air Force spirit’ and the Foundation of the Royal Air Force in the Interwar Years ROSS MAHONEY Independent Scholar Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT While the Royal Air Force was born in war, it was created in peace. In his 1919 memorandum on the Permanent Organization of the Royal Air Force, Air Marshal Sir Hugh Trenchard outlined his vision for the development of the Service. In this strategy, Trenchard developed the idea of generating an ‘Air Force spirit’ that provided the basis of the RAF’s development in the years after the First World War. The basis for this process was the creation of specific institutions and structures that helped generate a culture that allowed the RAF to establish itself as it dealt with challenges from its sister services. This article explores the character of that culture and ethos and in analysing the early years of the RAF through a cultural lens, suggests that Trenchard’s so-called ‘doctrine’ was focussed more on organisational developments rather than air power thinking as has often been suggested. In 1917, during the First World War and in direct response to the challenge of the aerial bombing of Great Britain, the British government decided to create an independent air service to manage the requirements of aerial warfare. With the formation of the Royal Air Force (RAF) on 1 April 1918, the Service’s senior leaders had to deal with the challenge of developing a new culture for the organisation that was consistent with the aims of the Air Force and delivered a sense of identity to its personnel. -

U DDLG Papers of the Lloyd-Greame 12Th Cent. - 1950 Family of Sewerby

Hull History Centre: Papers of the Lloyd-Greame Family of Sewerby U DDLG Papers of the Lloyd-Greame 12th cent. - 1950 Family of Sewerby Historical Background: The estate papers in this collection relate to the manor of Sewerby, Bridlington, which was in the hands of the de Sewerdby family from at least the twelfth century until descendants in a female line sold it in 1545. For two decades the estate passed through several hands before being bought by the Carliell family of Bootham, York. The Carliells moved to Sewerby and the four daughters of the first owner, John Carliell, intermarried with local gentry. His son, Tristram Carliell succeeded to the estates in 1579 and upon his death in 1618 he was succeeded by his son, Randolph or Randle Carliell. He died in 1659 and was succeeded by his son, Robert Carliell, who was married to Anne Vickerman, daughter and heiress of Henry Vickerman of Fraisthorpe. Robert Carliell died in in 1685 and his son Henry Carliell was the last male member of the family to live at Sewerby, dying in 1701 (Johnson, Sewerby Hall and Park, pp.4-9). Around 1714 Henry Carliell's heir sold the Sewerby estate to tenants, John and Mary Greame. The Greame family had originated in Scotland before moving south and establishing themselves in and around Bridlington. One line of the family were yeoman farmers in Sewerby, but John Greame's direct family were mariners and merchants in Bridlington. John Greame (b.1664) made two good marriages; first, to Grace Kitchingham, the daughter of a Leeds merchant of some wealth and, second to Mary Taylor of Towthorpe, a co-heiress. -

Geographical Reconnaissance by Aeroplane Photography, With

Geographical Reconnaissance by Aeroplane Photography, with Special Reference to the Work Done on the Palestine Front: Discussion Author(s): Geoffrey Salmond, Coote Hedley, H. S. L. Winterbotham, A. R. Hinks and E. M. Jack Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 55, No. 5 (May, 1920), pp. 370-376 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1780447 Accessed: 25-06-2016 21:41 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 137.99.31.134 on Sat, 25 Jun 2016 21:41:03 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms 370 GEOGRAPHICAL RECONNAISSANCE BY the great utility of maps which are sufficiently complete in local features to enable one to identify one's position by reference to the map detail. Most of the pre-war reconnaissance maps which I have used in the East, and which would be probably regarded as good of their type, involved the need of constantly stopping to take bearings on some distant known points in order to ascertain one's position, and this is a tiresome proceeding. -

Supreme Air Command: the Development of Royal Air Force Practice in the Second World

SUPREME AIR COMMAND THE DEVELOPMENT OF ROYAL AIR FORCE COMMAND PRACTICE IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR By DAVID WALKER A Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham January 2017 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines the development of RAF high command of the Metropolitan Air Force (MAF) during the Second World War. It sheds new light on the re-organisations of the Air Ministry in 1934, the RAF Command structure in 1936, and the tri-service debate in 1937 concerning the RAF proposal to establish a Supreme Air Commander (SAC). It reveals that while frontline expansion created an impetus for re-organisation, it was operational readiness that was the dominant factor in the re-structuring of the RAF. It examines the transition in RAF frontline organization from the mono-functional command system of 1936 to the multi- functional organisation that emerged after 1943 by looking at command structure and practice, personalities, and operational thinking. -

A Partial History of Connecticut College Lilah Raptopoulos Connecticut College, [email protected]

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Self-Designed Majors Honors Papers Self-Designed Majors 2011 A Partial History of Connecticut College Lilah Raptopoulos Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/selfdesignedhp Part of the Education Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Raptopoulos, Lilah, "A Partial History of Connecticut College" (2011). Self-Designed Majors Honors Papers. 3. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/selfdesignedhp/3 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Self-Designed Majors at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Self-Designed Majors Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. A Partial History of Connecticut College (conncollegehistory.lilahrap.com) An Honors Thesis presented by Lilah Raptopoulos in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major Field Connecticut College New London, Connecticut May 2011 Raptopoulos 1 /// TABLE OF CONTENTS /// ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 2 DEDICATION 4 INTRODUCTION 5 IDEALISM 10 LIBERAL ARTS 30 RELEVANCE 49 EQUITY 80 SHARED GOVERNANCE 101 CONCLUSION 125 IMAGE INDEX 131 BIBLIOGRAPHY 137 Raptopoulos 2 /// ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS /// It seems too obvious to say that this project would not have been possible without the people who make up the Connecticut College community – it was built out of their foundation. My gratitude belongs primarily to my two most important faculty mentors, Theresa Ammirati and Blanche Boyd. Dean Ammirati’s office was my first home at Connecticut College: a place of refuge from a new, scary place.