Lawrence of Airpower

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 29

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 29 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright 2003: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2003 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361-4231 Typeset by Creative Associates 115 Magdalen Road Oxford OX4 1RS Printed by Advance Book Printing Unit 9 Northmoor Park Church Road Northmoor OX29 5UH 3 CONTENTS BATTLE OF BRITAIN DAY. Address by Dr Alfred Price at the 5 AGM held on 12th June 2002 WHAT WAS THE IMPACT OF THE LUFTWAFFE’S ‘TIP 24 AND RUN’ BOMBING ATTACKS, MARCH 1942-JUNE 1943? A winning British Two Air Forces Award paper by Sqn Ldr Chris Goss SUMMARY OF THE MINUTES OF THE SIXTEENTH 52 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING HELD IN THE ROYAL AIR FORCE CLUB ON 12th JUNE 2002 ON THE GROUND BUT ON THE AIR by Charles Mitchell 55 ST-OMER APPEAL UPDATE by Air Cdre Peter Dye 59 LIFE IN THE SHADOWS by Sqn Ldr Stanley Booker 62 THE MUNICIPAL LIAISON SCHEME by Wg Cdr C G Jefford 76 BOOK REVIEWS. 80 4 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-Marshal -

Re-Visiting the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939 in Palestine

Oberlin Digital Commons at Oberlin Honors Papers Student Work 2016 Contested Land, Contested Representations: Re-visiting the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939 in Palestine Gabriel Healey Brown Oberlin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors Part of the History Commons Repository Citation Brown, Gabriel Healey, "Contested Land, Contested Representations: Re-visiting the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939 in Palestine" (2016). Honors Papers. 226. https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors/226 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Digital Commons at Oberlin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Oberlin. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Contested Land, Contested Representations: Re-visiting the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939 in Palestine Gabriel Brown Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Zeinab Abul-Magd Spring/2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgments………………………………………………………………………………...1 Map of Palestine, 1936……………………………………………………………………………2 Glossary…………………………………………………………………………………………...3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………….4 Chapter One……………………………………………………………………………………...15 Chapter Two……………………………………………………………………………………...25 Chapter Three…………………………………………………………………………………….37 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………….50 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………. 59 Brown 1 Acknowledgements Large research endeavors like this one are never undertaken alone, and I would be remiss if I didn’t thank the many people who have helped me along the way. I owe a huge debt to Shelley Lee, Jesse Gamoran, Gavin Ratcliffe, Meghan Mette, and Daniel Hautzinger, whose kind feedback throughout the year sharpened my ideas and improved the coherence of my work more times than I can count. A special thank you to Sam Coates-Finke and Leo Harrington, who were always ready to listen as I worked through the writing process. -

How the Luftwaffe Lost the Battle of Britain British Courage and Capability Might Not Have Been Enough to Win; German Mistakes Were Also Key

How the Luftwaffe Lost the Battle of Britain British courage and capability might not have been enough to win; German mistakes were also key. By John T. Correll n July 1940, the situation looked “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall can do more than delay the result.” Gen. dire for Great Britain. It had taken fight on the landing grounds, we shall Maxime Weygand, commander in chief Germany less than two months to fight in the fields and in the streets, we of French military forces until France’s invade and conquer most of Western shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, predicted, “In three weeks, IEurope. The fast-moving German Army, surrender.” England will have her neck wrung like supported by panzers and Stuka dive Not everyone agreed with Churchill. a chicken.” bombers, overwhelmed the Netherlands Appeasement and defeatism were rife in Thus it was that the events of July 10 and Belgium in a matter of days. France, the British Foreign Office. The Foreign through Oct. 31—known to history as the which had 114 divisions and outnumbered Secretary, Lord Halifax, believed that Battle of Britain—came as a surprise to the Germany in tanks and artillery, held out a Britain had lost already. To Churchill’s prophets of doom. Britain won. The RAF little longer but surrendered on June 22. fury, the undersecretary of state for for- proved to be a better combat force than Britain was fortunate to have extracted its eign affairs, Richard A. “Rab” Butler, told the Luftwaffe in almost every respect. -

Security & Defence European

a 7.90 D 14974 E D European & Security ES & Defence 6/2019 International Security and Defence Journal COUNTRY FOCUS: AUSTRIA ISSN 1617-7983 • Heavy Lift Helicopters • Russian Nuclear Strategy • UAS for Reconnaissance and • NATO Military Engineering CoE Surveillance www.euro-sd.com • Airborne Early Warning • • Royal Norwegian Navy • Brazilian Army • UAS Detection • Cockpit Technology • Swiss “Air2030” Programme Developments • CBRN Decontamination June 2019 • CASEVAC/MEDEVAC Aircraft • Serbian Defence Exports Politics · Armed Forces · Procurement · Technology ANYTHING. In operations, the Eurofighter Typhoon is the proven choice of Air Forces. Unparalleled reliability and a continuous capability evolution across all domains mean that the Eurofighter Typhoon will play a vital role for decades to come. Air dominance. We make it fly. airbus.com Editorial Europe Needs More Pragmatism The elections to the European Parliament in May were beset with more paradoxes than they have ever been. The strongest party which will take its seats in the plenary chambers in Brus- sels (and, as an expensive anachronism, also in Strasbourg), albeit only for a brief period, is the Brexit Party, with 29 seats, whose programme is implicit in their name. Although EU institutions across the entire continent are challenged in terms of their public acceptance, in many countries the election has been fought with a very great deal of emotion, as if the day of reckoning is dawning, on which decisions will be All or Nothing. Some have raised concerns about the prosperous “European Project”, which they see as in dire need of rescue from malevolent sceptics. Others have painted an image of the decline of the West, which would inevitably come about if Brussels were to be allowed to continue on its present course. -

1 P247 Musketry Regulations, Part II RECORDS' IDENTITY STATEMENT Reference Number

P247 Musketry Regulations, Part II RECORDS’ IDENTITY STATEMENT Reference number: GB1741/P247 Alternative reference number: Title: Musketry Regulations, Part II Dates of creation: 1910 Level of description: Fonds Extent: 1 volume Format: Paper RECORDS’ CONTEXT Name of creators: The War Office Administrative history: The War Office was a department of the British Government, responsible for the administration of the British Army between the 17th century and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the Ministry of Defence. The name "War Office" is also often given to the former home of the department, the Old War Office Building on Horse Guards Avenue, London. The War Office declined greatly in importance after the First World War, a fact illustrated by the drastic reductions in its staff numbers during the inter-war period. On 1 April 1920, it employed 7,434 civilian staff; this had shrunk to 3,872 by 1 April 1930. Its responsibilities and funding were also reduced. In 1936, the government of Stanley Baldwin appointed a Minister for Co-ordination of Defence, who worked outside of the War Office. When Winston Churchill became Prime Minister in 1940, he bypassed the War Office altogether and appointed himself Minister of Defence (though there was, curiously, no ministry of defence until 1947). Clement Attlee continued this arrangement when he came to power in 1945 but appointed a separate Minister of Defence for the first time in 1947. In 1964, the present form of the Ministry of Nucleus: The Nuclear and Caithness Archives 1 Defence was established, unifying the War Office, Admiralty, and Air Ministry. -

The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Schriften Des Historischen Kollegs

The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Schriften des Historischen Kollegs Herausgegeben von Andreas Wirsching Kolloquien 91 The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Herausgegeben von Holger Afflerbach An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Schriften des Historischen Kollegs herausgegeben von Andreas Wirsching in Verbindung mit Georg Brun, Peter Funke, Karl-Heinz Hoffmann, Martin Jehne, Susanne Lepsius, Helmut Neuhaus, Frank Rexroth, Martin Schulze Wessel, Willibald Steinmetz und Gerrit Walther Das Historische Kolleg fördert im Bereich der historisch orientierten Wissenschaften Gelehrte, die sich durch herausragende Leistungen in Forschung und Lehre ausgewiesen haben. Es vergibt zu diesem Zweck jährlich bis zu drei Forschungsstipendien und zwei Förderstipendien sowie alle drei Jahre den „Preis des Historischen Kollegs“. Die Forschungsstipendien, deren Verleihung zugleich eine Auszeichnung für die bisherigen Leis- tungen darstellt, sollen den berufenen Wissenschaftlern während eines Kollegjahres die Möglich- keit bieten, frei von anderen Verpflichtungen eine größere Arbeit abzuschließen. Professor Dr. Hol- ger Afflerbach (Leeds/UK) war – zusammen mit Professor Dr. Paul Nolte (Berlin), Dr. Martina Steber (London/UK) und Juniorprofessor Simon Wendt (Frankfurt am Main) – Stipendiat des Historischen Kollegs im Kollegjahr 2012/2013. Den Obliegenheiten der Stipendiaten gemäß hat Holger Afflerbach aus seinem Arbeitsbereich ein Kolloquium zum Thema „Der Sinn des Krieges. Politische Ziele und militärische Instrumente der kriegführenden Parteien von 1914–1918“ vom 21. -

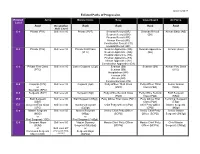

Enlisted Paths of Progression Chart

Updated 2/24/17 Enlisted Paths of Progression Enlisted Army Marine Corps Navy Coast Guard Air Force Level Rank Occupation Rank Rank Rank Rank Skill Level E-1 Private (PV1) Skill level 10 Private (PVT) Seaman Recruit (SR) Seaman Recruit Airman Basic (AB) Seaman Recruit (SR) (SR) Fireman Recruit (FR) Airman Recruit (AR) Construction Recruit (CR) Hospital Recruit (HR) E-2 Private (PV2) Skill level 10 Private First Class Seaman Apprentice (SA) Seaman Apprentice Airman (Amn) (PFC) Seaman Apprentice (SA) (SA) Hospital Apprentice (HA) Fireman Apprentice (FA) Airman Apprentice (AA) Construction Apprentice (CA) E-3 Private First Class Skill level 10 Lance Corporal (LCpl) Seaman (SN) Seaman (SN) Airman First Class (PFC) Seaman (SN) (A1C) Hospitalman (HN) Fireman (FN) Airman (AN) Constructionman (CN) E-4 Corporal (CPL) Skill level 10 Corporal (Cpl) Petty Officer Third Class Petty Officer Third Senior Airman or (PO3) Class (PO3) (SRA) Specialist (SPC) E-5 Sergeant (SGT) Skill level 20 Sergeant (Sgt) Petty Office Second Class Petty Office Second Staff Sergeant (PO2) Class (PO2) (SSgt) E-6 Staff Sergeant Skill level 30 Staff Sergeant (SSgt) Petty Officer First Class (PO1) Petty Officer First Technical Sergeant (SSG) Class (PO1) (TSgt) E-7 Sergeant First Class Skill level 40 Gunnery Sergeant Chief Petty Officer (CPO) Chief Petty Officer Master Sergeant (SFC) (GySgt) (CPO) (MSgt) E-8 Master Sergeant Skill level 50 Master Sergeant Senior Chief Petty Officer Senior Chief Petty Senior Master (MSG) (MSgt) (SCPO) Officer (SCPO) Sergeant (SMSgt) or or First Sergeant (1SG) First Sergeant (1stSgt) E-9 Sergeant Major Skill level 50 Master Gunnery Master Chief Petty Officer Master Chief Petty Chief Master (SGM) Sergeant (MGySgt) (MCPO) Officer (MCPO) Sergeant (CMSgt) or Skill level 60* or Command Sergeant (*For some fields, Sergeant Major Major (CSM) not all.) (SgtMaj) . -

Freeman's Folly

Chapter 9 Freeman’s Folly: The Debate over the Development of the “Unarmed Bomber” and the Genesis of the de Havilland Mosquito, 1935–1940 Sebastian Cox The de Havilland Mosquito is, justifiably, considered one of the most famous and effective military aircraft of the Second World War. The Mosquito’s devel- opment is usually portrayed as being a story of a determined and independent aircraft company producing a revolutionary design with very little input com- ing from the official Royal Air Force design and development process, which normally involved extensive consultation between the Air Ministry’s technical staff and the aircraft’s manufacturer, culminating in an official specification being issued and a prototype built. Instead, so the story goes, de Havilland’s design team thought up the concept of the “unarmed speed bomber” all by themselves and, despite facing determined opposition from the Air Ministry and the raf, got it adopted by persuading one important and influential senior officer, Wilfrid Freeman, to put it into production (Illustration 9.1).1 Thus, before it proved itself in actuality a world-beating design, it was known in the Ministry as “Freeman’s Folly”. Significantly, even the UK Official History on the “Design and Development of Weapons”, published in 1964, perpetuated this explanation, stating that: When … [de Havilland] found itself at the beginning of the war short of orders and anxious to contribute to the war effort they proceeded to design an aeroplane without any official prompting from the Air Minis- try. They had to think out for themselves the whole tactical and strategic purpose of the aircraft, and thus made a number of strategic and tactical assumptions which were not those of the Air Staff. -

The Felixstowe Society Newsletter

THE FELIXSTOWE SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Issue No. 115 May 2017 Registered Charity No. 27744 To accompany this issue: A special booklet to follow up on the Bala Cottage issue. Can You Help? Please read Page 6 to find out. 1 The Felixstowe Society is established for the public benefit of people who either live or work in Felixstowe and Walton. Members are also welcome from The Trimleys and the surrounding villages. The Society endeavours to: stimulate public interest in these areas promote high standards of planning and architecture and secure the improvement, protection, development and preservation of the local environment. Cover photo: On the left - Gulpher Pond. Lower right - The Grove Contents 3 Notes from the Chairman 4 Calendar - May to December 5 Society News 7 Speaker Evening - Richard Harvey 8 Speaker Evening - Sister Marian 9 Visit to the Port of Felixstowe 10 Speaker Evening - Nigel Pickover 11 Beach Clean 12 The Felixstowe Walkers 13 The Society Members’ Feature - Michael and Penny Thomas 16 The Beach Hut and Chalet Owners 18 News from Felixstowe Museum 19 Research Corner 27 Part 3 - Bowls in Felixstowe 21 Felixstowe Community Hospital League of Friends 23 Thomas Cotman and Charles Emeny 25 Planning Applications - January to March 2017 26 Listed Buildings in Felixstowe and Walton 28 Photo Quiz Contacts: Roger Baker - Chairman until the AGM - 01394 282526 Hilary Eaton - Treasurer - 01394 549321 2 Notes from the Chairman These are my final “Notes” as Chairman of The Society. You might remember that I resigned on a previous occasion at the end of 2015 when Phil Hadwen was due to take over from me. -

Privatization of Public Social Services a Background Paper Demetra Smith Nightingale, Nancy M

Privatization of Public Social Services A Background Paper Demetra Smith Nightingale, Nancy M. Pindus This paper was prepared at the Urban Institute for U.S. Department of Labor, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Document date: October 15, 1997 Policy, under DOL Contract No. J-9-M-5-0048, #15. Released online: October 15, 1997 Opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the positions of DOL, the Urban Institute or its sponsors. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Urban Institute, its board, its sponsors, or other authors in the series 1. Introduction The purposes of the paper are to provide a general overview of the extent of privatization of public services in the areas of social services, welfare, and employment; rationales for privatizing service delivery, and evidence of effectiveness or problems. Examples are included to highlight specific types of privatization and actual operational experience. The paper is not intended to be a comprehensive treatment of the overall subject of privatization, but rather a brief review of issues and experiences specifically related to the delivery of employment and training, welfare, and social services. The key points that are drawn from a review of the literature are: There is no single definition of privatization. Privatization covers a broad range of methods and models, including contracting out for services, voucher programs, and even the sale of public assets to the private sector. But for the purposes of this paper, privatization refers to the provision of publicly-funded services and activities by non-governmental entities. -

Effects-Based Operations and the Law of Aerial Warfare

Washington University Global Studies Law Review Volume 5 Issue 2 January 2006 Effects-based Operations and the Law of Aerial Warfare Michael N. Schmitt George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies Part of the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Michael N. Schmitt, Effects-based Operations and the Law of Aerial Warfare, 5 WASH. U. GLOBAL STUD. L. REV. 265 (2006), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies/vol5/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Global Studies Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Washington University Global Studies Law Review VOLUME 5 NUMBER 2 2006 EFFECTS-BASED OPERATIONS AND THE LAW OF AERIAL WARFARE MICHAEL N. SCHMITT* Law responds almost instinctively to tectonic shifts in warfare.1 For instance, the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949 constituted a dramatic reaction to the suffering of civilian populations during World War II.2 Similarly, the 1977 Protocols Additional3 updated and expanded the law of armed conflict (LOAC) in response both to the growing prevalence of non-international armed conflicts and wars of national liberation and to the recognized need to codify the norms governing the conduct of hostilities.4 In light of this symbiotic relationship, it is essential that LOAC experts carefully monitor developments in military affairs, because such developments may well either strain or strengthen aspects of that body of law.5 As an example, the widespread use in Iraq of civilian contractors and * Professor of International Law and Director, Program in Advanced Security Studies, George C. -

PDF File, 139.89 KB

Armed Forces Equivalent Ranks Order Men Women Royal New Zealand New Zealand Army Royal New Zealand New Zealand Naval New Zealand Royal New Zealand Navy: Women’s Air Force: Forces Army Air Force Royal New Zealand New Zealand Royal Women’s Auxilliary Naval Service Women’s Royal New Zealand Air Force Army Corps Nursing Corps Officers Officers Officers Officers Officers Officers Officers Vice-Admiral Lieutenant-General Air Marshal No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent Rear-Admiral Major-General Air Vice-Marshal No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent Commodore, 1st and Brigadier Air Commodore No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent 2nd Class Captain Colonel Group Captain Superintendent Colonel Matron-in-Chief Group Officer Commander Lieutenant-Colonel Wing Commander Chief Officer Lieutenant-Colonel Principal Matron Wing Officer Lieutentant- Major Squadron Leader First Officer Major Matron Squadron Officer Commander Lieutenant Captain Flight Lieutenant Second Officer Captain Charge Sister Flight Officer Sub-Lieutenant Lieutenant Flying Officer Third Officer Lieutenant Sister Section Officer Senior Commis- sioned Officer Lieutenant Flying Officer Third Officer Lieutenant Sister Section Officer (Branch List) { { Pilot Officer Acting Pilot Officer Probationary Assistant Section Acting Sub-Lieuten- 2nd Lieutenant but junior to Third Officer 2nd Lieutenant No equivalent Officer ant Navy and Army { ranks) Commissioned Officer No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No