The London Guilds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue of the Earl Marshal's Papers at Arundel

CONTENTS CONTENTS v FOREWORD by Sir Anthony Wagner, K.C.V.O., Garter King of Arms vii PREFACE ix LIST OF REFERENCES xi NUMERICAL KEY xiii COURT OF CHIVALRY Dated Cases 1 Undated Cases 26 Extracts from, or copies of, records relating to the Court; miscellaneous records concerning the Court or its officers 40 EARL MARSHAL Office and Jurisdiction 41 Precedence 48 Deputies 50 Dispute between Thomas, 8th Duke of Norfolk and Henry, Earl of Berkshire, 1719-1725/6 52 Secretaries and Clerks 54 COLLEGE OF ARMS General Administration 55 Commissions, appointments, promotions, suspensions, and deaths of Officers of Arms; applications for appointments as Officers of Arms; lists of Officers; miscellanea relating to Officers of Arms 62 Office of Garter King of Arms 69 Officers of Arms Extraordinary 74 Behaviour of Officers of Arms 75 Insignia and dress 81 Fees 83 Irregularities contrary to the rules of honour and arms 88 ACCESSIONS AND CORONATIONS Coronation of King James II 90 Coronation of King George III 90 Coronation of King George IV 90 Coronation of Queen Victoria 90 Coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra 90 Accession and Coronation of King George V and Queen Mary 96 Royal Accession and Coronation Oaths 97 Court of Claims 99 FUNERALS General 102 King George II 102 Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales 102 King George III 102 King William IV 102 William Ewart Gladstone 103 Queen Victoria 103 King Edward VII 104 CEREMONIAL Precedence 106 Court Ceremonial; regulations; appointments; foreign titles and decorations 107 Opening of Parliament -

This Is a Pre-Copyedited, Author-Produced Version of an Article Accepted for Publication in Twentieth Century British History Following Peer Review

1 This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Twentieth Century British History following peer review. The version of record, Brett Holman, ‘The shadow of the airliner: commercial bombers and the rhetorical destruction of Britain, 1917-35’, Twentieth Century British History 24 (2013), 495-517, is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/tcbh/hws042. The shadow of the airliner: commercial bombers and the rhetorical destruction of Britain, 1917-19351 Brett Holman, Independent Scholar Aerial bombardment was widely believed to pose an existential threat to Britain in the 1920s and 1930s. An important but neglected reason for this was the danger from civilian airliners converted into makeshift bombers, the so-called ‘commercial bomber’: an idea which arose in Britain late in the First World War. If true, this meant that even a disarmed Germany 1 The author would like to thank: the referees, for their detailed comments; Chris A. Williams, for his assistance in locating a copy of Cd. 9218; and, for their comments on a draft version of this article, Alan Allport, Christopher Amano- Langtree, Corry Arnold, Katrina Gulliver, Wilko Hardenberg, Lester Hawksby, James Kightly, Beverley Laing, Ross Mahoney, Andre Mayer, Bob Meade, Andrew Reid, and Alun Salt. Figure 1 first appeared in the Journal of the Royal Institute of International Affairs, Vol, 8, No. 4, July 1929, pp, 289-317, and is reproduced with permission. 2 could potentially attack Britain with a large bomber force thanks to its successful civil aviation industry. By the early 1930s the commercial bomber concept appeared widely in British airpower discourse. -

“Powerful Arms and Fertile Soil”

“Powerful Arms and Fertile Soil” English Identity and the Law of Arms in Early Modern England Claire Renée Kennedy A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History and Philosophy of Science University of Sydney 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My greatest thanks and appreciation to Ofer Gal, who supervised my PhD with constant interest, insightfulness and support. This thesis owes so much to his helpful conversation and encouraging supervision and guidance. I have benefitted immensely from the suggestions and criticisms of my examiners, John Sutton, Nick Wilding, and Anthony Grafton, to whom I owe a particular debt. Grafton’s suggestion during the very early stages of my candidature that the quarrel between William Camden and Ralph Brooke might provide a promising avenue for research provided much inspiration for the larger project. I am greatly indebted to the staff in the Unit for History and Philosophy of Science: in particular, Hans Pols for his unwavering support and encouragement; Daniela Helbig, for providing some much-needed motivation during the home-stretch; and Debbie Castle, for her encouraging and reassuring presence. I have benefitted immensely from conversations with friends, in and outside the Unit for HPS. This includes, (but is not limited to): Megan Baumhammer, Sahar Tavakoli, Ian Lawson, Nick Bozic, Gemma Lucy Smart, Georg Repnikov, Anson Fehross, Caitrin Donovan, Stefan Gawronski, Angus Cornwell, Brenda Rosales and Carrie Hardie. My particular thanks to Kathryn Ticehurst and Laura Sumrall, for their willingness to read drafts, to listen, and to help me clarify my thoughts and ideas. My thanks also to the Centre for Editing Lives and Letters, University College London, and the History of Science Program, Princeton University, where I benefitted from spending time as a visiting research student. -

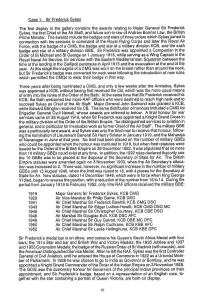

Case 1: Sir Frederick Sykes the First Display in the Gallery Contains

Case 1: Sir Frederick Sykes The first display in the gallery contains the awards relating to Major General Sir Frederick Sykes, the first Chief of the Air Staff, and future son-in-law of Andrew Bonnar Law, the British Prime Minister. The awards include the badges and stars of three orders which Sykes joined in connection with his services in command of the Royal Flying Corps and later the Royal Air Force, with the badge of a CMG, the badge and star of a military division KCB, and the sash badge and star of a military division GBE. Sir Frederick was appointed a Companion in the Order of St Michael and St George on 1 January 1916, while serving as a Wing Captain in the Royal Naval Air Service, for services with the Eastern Mediterranean Squadron between the time of the landing in the Gallipoli peninsula in April 1915 and the evacuation at the end of the year. At this stage the insignia of a CMG was worn on the breast rather than around the neck, but Sir Frederick’s badge was converted for neck wear following the introduction of new rules which permitted the CMGs to wear their badge in that way. Three years after being nominated a CMG, and only a few weeks after the Armistice, Sykes was appointed a KCB, without having first received the CB, which was the more usual means of entry into the ranks of the Order of the Bath. At the same time that Sir Frederick received his KCB, the Bath welcomed two more RAF officers who were destined to reach high rank and to succeed Sykes as Chief of the Air Staff: Major General John Salmond was granted a KCB, while Edward Ellington received his CB. -

Kleyser Charles & Co. Watch & Clockma.4 Broadst. Bloowb

. 1852.] COMMERCIAL DiRECTORY~ 831 Kin loch Wm.cheesemong.to her Majesty ,48Jermyn st.St.Jas's Kirkham Arthur Leech,watchmaker&: jeweller, IM,& pawn• Kinnear George, merchant, see Ellice, Kinnear & Co ~broker & silversmith, 318 Strand Kinnebrook Wm. artist, 9 Wyndham place, Bryanstone sq Kirkham John, civil engineer, 3 Tonbridg'e place, Euston sq Kinnell George, hemp & flax merchant, 6 Vine st. Minories Kirkham John, commission merchant, 1 Lime street square Kinner Thomas, carrier's agent, New inn yard, Old Bailey Kirk land Sir John & Co. army agents, 80 Pall mall Kinseley Thomas, truss maker, 17 Wych street, Strand Kirkman & Engleheart, auctioneers, 58 King Wm. st. City Kinsey James H. leather dresser & dyer, 83 Bermondsey st Kirk man J oseph & Son, pianoforte m a. to her Majesty,3 Sobo I Kinsey William, solicitor, 20 Bloomsbury square sq. & 9Dean st.Soho; factory,Dufour's pi. Br01id st.Gidn.sq Kintrea Archibald & Co. soap makers & bone & other manure Kirkman & T.backray, who. stationers,5 Old Fish st.Doc.com merchants, 22! Great George street, Bermondsey Kirk man Hyde, surveyor, 29 Somerset street, Portman sq Klnzigthal Mining A1sociation (George Copeland Capper, Kirkman John James, solicitor, 27 Laurence Pountney lane secretary), 1 Adelaide place, London bridge Kirkmann,Brown&Co.e.in.col.&metal brok.2St.Dunstan's hl Kipling Brothers, french importers, 28 Silver st. Wood st Kirkmann Abraham, barrister, 89 Chancery lane Kipling Henry & Co. french importers, 28 Silver st. Wood et Kirkness Jas. tinplate worker,38Gt.Prescot st.Goodman's fi KipJing John & Francis, who.carpet wa.ll Addle st. Wood st Kirkpatrick John, barrister, 2 Mitre court buildingli, Temple Kip ling Wm. -

Archaeological Excavations in the City of London 1907

1 in 1991, and records of excavations in the City of Archaeological excavations London after 1991 are not covered in this Guide . in the City of London 1907– The third archive of excavations before 1991 in the City concerns the excavations of W F Grimes 91 between 1946 and 1962, which are the subject of a separate guide (Shepherd in prep). Edited by John Schofield with Cath Maloney text of 1998 The Guildhall Museum was set up in 1826, as an Cite as on-line version, 2021 adjunct to Guildhall Library which had been page numbers will be different, and there are no established only two years before. At first it illustrations in this version comprised only a small room attached to the original text © Museum of London 1998 Library, which itself was only a narrow corridor. In 1874 the Museum transferred to new premises in Basinghall Street, which it was to occupy until Contents 1939. After the Second World War the main gallery was subdivided with a mezzanine floor and Introduction .................................................. 1 furnished with metal racking for the Library, and An outline of the archaeology of the City from this and adjacent rooms coincidentally became the the evidence in the archive ............................. 6 home of the DUA from 1976 to 1981. The character of the archive and the principles behind its formation ..................................... 14 The history of the Guildhall Museum, and of the Editorial method and conventions ................ 18 London Museum with which it was joined in 1975 Acknowledgements ..................................... 20 to form the Museum of London, has been written References .................................................. 20 by Francis Sheppard (1991); an outline of archaeological work in the City of London up to the Guildhall Museum sites before 1973 ........... -

The National Archives Prob 11/99/135 1 ______

THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES PROB 11/99/135 1 ________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY: The document below is the Prerogative Court of Canterbury copy of the will, dated 20 February 1597 and 13 July 1601, and proved 19 February 1602, of Mary (nee Matthew) Wolley Langton Judde Altham (d. 15 January 1602), whose granddaughter, Cecilia Baynham, married Sir William Throckmorton, a first cousin of Mary (nee Tracy) Hoby Vere, wife of Oxford’s first cousin, Horatio Vere. The testatrix’ first husband appears to have been Thomas Wolley, who had a business partnership with Thomas Bacon, brother of Lord Burghley’s brother-in-law, Sir Nicholas Bacon. FAMILY BACKGROUND The testatrix was the daughter and heir of Thomas Matthew, esquire, of St James, Colchester, Essex. See the will of Thomas Matthew, ERO D/ABW 25/35, and the WikiTree profile for the testatrix at: https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Mathew-325 See also the entry for the testatrix at: http://www.tudorwomen.com/?page_id=695 In 1558 the testatrix was granted a coat of arms. See Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles, A Complete Guide to Heraldry, (New York: Gramercy Books, 1993), pp. 574-5 at: http://www7b.biglobe.ne.jp/~bprince/hr/foxdavies/fdguide35.htm MARRIAGES AND ISSUE Testatrix’ first marriage The testatrix married firstly a husband surnamed Wolley, likely the London grocer, Thomas Wolley. In his will, the testatrix’ second husband, Thomas Langton (d.1551), mentions ‘Thomas Bacon, citizen and salter of London’, and appoints him overseer. The History of Parliament entry for Thomas Bacon (c.1505 – 1573 or later), states that he had a business partnership with Thomas Wolley. -

The Scrivener

The Scrivener THE NEWSLETTER OF THE WORSHIPFUL COMPANY OF SCRIVENERS OF THE CITY OF LONDON ISSUE 23 : SPRING 2015 A Freedom at the Mansion House It was a little early for Christmas perhaps, as the annual Quill and is completing his ab initio pilot Pen Lunch took place in the last week of November, but the training. He is clearly not one to sit at a Lord Mayor certainly seemed pleased with his gifts from the desk with a quill in his hand for too long. Scriveners. There no surprises, of course—he’d even seen the We also welcomed Sheriff Fiona Adler main gift before, when he signed himself into office—but he and her consort Mr David Moss. An now has a souvenir of the Silent Ceremony that will serve to extract from the Lord Mayor’s address to remind him of the start of his mayoral year. the Company can be read on page 7. The Master also presented him with the customary cheque towards the Lord Mayor’s Appeal and the Lady Mayoress received one of the new Scriveners’ fountain pens. As always, it was a very convivial occasion, affording us another opportunity to sample Mansion House hospitality in the Old Ballroom on the second floor, and it was unique in that Mr Allan Kill was sworn in as a Freeman immediately following the lunch and is, to this Clerk’s knowledge, the first Scrivener to be accorded the distinction of being admitted to the Company in the Lord Mayor’s residence. That he looked a little bemused was perhaps to be expected, especially as the Lord Mayor gave him a personal mention in his address. -

CAMDEN STREET NAMES and Their Origins

CAMDEN STREET NAMES and their origins © David A. Hayes and Camden History Society, 2020 Introduction Listed alphabetically are In 1853, in London as a whole, there were o all present-day street names in, or partly 25 Albert Streets, 25 Victoria, 37 King, 27 Queen, within, the London Borough of Camden 22 Princes, 17 Duke, 34 York and 23 Gloucester (created in 1965); Streets; not to mention the countless similarly named Places, Roads, Squares, Terraces, Lanes, o abolished names of streets, terraces, Walks, Courts, Alleys, Mews, Yards, Rents, Rows, alleyways, courts, yards and mews, which Gardens and Buildings. have existed since c.1800 in the former boroughs of Hampstead, Holborn and St Encouraged by the General Post Office, a street Pancras (formed in 1900) or the civil renaming scheme was started in 1857 by the parishes they replaced; newly-formed Metropolitan Board of Works o some named footpaths. (MBW), and administered by its ‘Street Nomenclature Office’. The project was continued Under each heading, extant street names are after 1889 under its successor body, the London itemised first, in bold face. These are followed, in County Council (LCC), with a final spate of name normal type, by names superseded through changes in 1936-39. renaming, and those of wholly vanished streets. Key to symbols used: The naming of streets → renamed as …, with the new name ← renamed from …, with the old Early street names would be chosen by the name and year of renaming if known developer or builder, or the owner of the land. Since the mid-19th century, names have required Many roads were initially lined by individually local-authority approval, initially from parish named Terraces, Rows or Places, with houses Vestries, and then from the Metropolitan Board of numbered within them. -

Andrew Johnston Phd Thesis

WILLIAM PAGET AND THE LATE-HENRICAN POLITY, 1543- 1547 Andrew Johnston A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St. Andrews 2004 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/2762 This item is protected by original copyright William Paget and the late-Henrican polity, 1543-1547 Andrew Johnston A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of St Andrews December 2003 Paginated blank pages are scanned as found in original thesis No information • • • IS missing Declarations (i) I, Andrew Johnston, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately one hundred thousand words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. Date; signature of candidate; (ii) I was admitted as a research student in October 1998 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in October 1999; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 1999 and 2003. - -- ...... _- --.-.:.. - - ..:... --._---- :-,.:. -.:. Date; signature of candidate; - ...- - ~,~.~~~- ~.~:.:. - . (iii) I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title “Poetick Rage” to Rage of Party: English Political Verse, 1678-1685 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/67k814zg Author McLaughlin, Leanna Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE “Poetick Rage” to Rage of Party: English Political Verse, 1678-1685 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Leanna Hope McLaughlin December 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Thomas Cogswell, Chairperson Dr. Randolph Head Dr. Patricia Fumerton Copyright by Leanna Hope McLaughlin 2018 The Dissertation of Leanna Hope McLaughlin is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS While saving the best for last may seem like a great idea, the acknowledgements are actually some of the harder words I have ever written. How does one put into words the boundless gratitude to the people and organizations that have made this book possible? Still, I must try. This dissertation simply would not have been possible without the patience, encouragement, and guidance of Dr. Thomas Cogswell. In addition to pointing me in the direction of the most delightful and scandalous sources in early modern England, Tom’s help and advice helped me craft the larger argument and his laughter at the content fueled my drive. Thanks to Tom I will eternally move “onward and upward.” I owe Dr. Randolph Head a great deal for his unending support, his uncanny ability to help me see the narrative flow and the bigger picture, and his dogmatic attention to questions of historical practice. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/148274 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-10 and may be subject to change. NATHANIEL THOMPSON TORY PRINTER, BALLAD MONGER AND PROPAGANDIST G.M. Peerbooms NATHANIEL THOMPSON Promotor: Prof. T.A. Birrell NATHANIEL THOMPSON TORY PRINTER, BALLAD MONGER AND PROPAGANDIST Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor in de letteren aan de Katholieke Universiteit te Nijmegen, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus Prof. Dr. J.H.G.I. Giesbers volgens besluit van het College van Dekanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 28 juni 1983 des namiddags te 2 uur precies door GERARD MARIA PEERBOOMS geboren te Bom Sneldruk Boulevard Enschede ISBN 90-9000482-3 С. 19Θ3 G.M.Peerbooms,Instituut Engels-Amerikaans Katholieke Universiteit,Erasmusplein 1«Nijmegen. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the authorities and staffs of the following libraries and record offices for permission to examine books and manuscripts in their possession, for their readiness to answer my queries and to provide microfilms: the British Library, London; the Corporation of London Record Office; Farm Street Church Library, London; the Greater London Record Office; the Guildhall Library, London; Heythrop College Library, London; the House of Lords Record Office, London; Lambeth Palace Library, London; the Public Record Office, London; St. Bride's Printing Library, London; the Stationers' Company, London; Westminster Public Library, London, the Bodleian Library, Oxford; Christ Church College Library, All Souls Collecte Library, Merton College Library, New College Library, Worcester College Library, Oxford; Chetam's Library, Manchester; the National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh; the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University; the Houghton Library, Harvard University; the H.E.