A Constructivist Grounded Theory Exploration of Wellbeing in Female

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estate 5 BHK Brochure

4 & 5 BHK LUXURY HOMES Hiranandani Estate, Thane Hiranandani Estate, Off Ghodbunder Road, Thane (W) Call:(+91 22) 2586 6000 / 2545 8001 / 2545 8760 / 2545 8761 Corp. Off.: Olympia, Central Avenue, Hiranandani Business Park, Powai, Mumbai - 400 076. [email protected] • www.hiranandani.com Rodas Enclave-Leona, Royce-4 BHK & Basilius-5 BHK are mortgaged with HDFC Ltd. The No Objection Certificate (NOC)/permission of the mortgagee Bank would be provided for sale of flats/units/property, if required. Welcome to the Premium Hiranandani Living! ABUNDANTLY YOURS Standard apartment of Basilius building for reference purpose only. The furniture & fixtures shown in the above flat are not part of apartment amenities. EXTRAVAGANTLY, oering style with a rich sense of prestige, quality and opulence, heightened by the cascades of natural light and spacious living. Actual image shot at Rodas Enclave, Thane. LUXURIOUSLY, navigating the chasm between classic and contemporary design to complete the elaborated living. • Marble flooring in living, dining and bedrooms • Double glazed windows • French windows in living room • Large deck in living/dining with sliding balcony doors Standard apartment of Basilius building for reference purpose only. The furniture & fixtures shown in the above flat are not part of apartment amenities. CLASSICALLY, veering towards the modern and eclectic. Standard apartment of Basilius building for reference purpose only. The furniture & fixtures shown in the above flat are not part of apartment amenities. EXCLUSIVELY, meant for the discerning few! Here’s an access to gold class living that has been tastefully designed and thoughtfully serviced, oering only and only a ‘royal treatment’. • Air-conditioner in living, dining and bedrooms • Belgian wood laminate flooring in common bedroom • Space for walk–in wardrobe in apartments • Back up for selected light points in each flat Standard apartment of Basilius building for reference purpose only. -

Download 3.94 MB

Environmental Monitoring Report Semiannual Report (March–August 2019) Project Number: 49469-007 Loan Number: 3775 February 2021 India: Mumbai Metro Rail Systems Project Mumbai Metro Rail Line-2B Prepared by Mumbai Metropolitan Development Region, Mumbai for the Government of India and the Asian Development Bank. This environmental monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ABBREVATION ADB - Asian Development Bank ADF - Asian Development Fund CSC - construction supervision consultant AIDS - Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome EA - execution agency EIA - environmental impact assessment EARF - environmental assessment and review framework EMP - environmental management plan EMR - environmental Monitoring Report ESMS - environmental and social management system GPR - Ground Penetrating Radar GRM - Grievance Redressal Mechanism IEE - initial environmental examination MMRDA - Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority MML - Mumbai Metro Line PAM - project administration manual SHE - Safety Health & Environment Management Plan SPS - Safeguard Policy Statement WEIGHTS AND MEASURES km - Kilometer -

Form 990-PF 2017

l efile GRAPHIC print - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN:93491134045128 OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation Department of the Trea^un or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Internal Rev enue Ser ice 2017 ► Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. ► Information about Form 990-PF and its instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990pf. For calendar year 2017, or tax year beginning 01 -01-2017 , and ending 12-31-2017 Name of foundation HORTON FAMILY FOUNDATION 77-0496939 Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 26030 ALTAMONT ROAD City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code LOS ALTOS HILLS, CA 94022 C If exemption application is pending, check here q G Check all that apply q Initial return q Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here ► q Final return q Amended return 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% q test, check here and attach computation ► El Address change El Name change E If private foundation status was terminated H Check typ e of org anization q Section 501(c)(3) exem p t p rivate foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ► q Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust q Other taxable private foundation I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method 9 Cash q Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination of year (from Part II, col (c), under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here q ► line 16)101$ 906,110 Other (specify) (Part I, column (d) must be on cash basis ) Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (The total ( a) Revenue and (d) Disbursements (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net for charitable of amounts n columns (b), (c), and (d) may not necessarily expenses per income income purposes books basis equal the amounts in column (a) (see instructions) ) (cash s only) 1 Contributions, gifts, grants, etc , received (attach 300,000 schedule) 2 Check ► W if the foundation is not required to attach Sch B . -

Floor, Cuffe Parade, Mumbai 400 005 Tel

Before the MAHARASHTRA ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION World Trade Centre, Centre No.1, 13th Floor, Cuffe Parade, Mumbai 400 005 Tel. 022 22163964/65/69 Fax 22163976 Email: [email protected] Website: www.merc.gov.in Case No. 202 of 2020 Suo Motu Proceeding in the matter of Grid Failure in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region on 12 October 2020 at 10.02 Hrs. Coram I.M. Bohari, Member Mukesh Khullar, Member Parties to the proceeding 1. Maharashtra State Electricity Transmission Co. Ltd. 2. Maharashtra State Electricity Distribution Co. Ltd. 3. BEST Undertaking 4. Maharashtra State Load Dispatch Centre 5. State Transmission Utility 6. Tata Power Company Ltd.-Generation 7. Tata Power Company Ltd.- Transmission 8. Tata Power Company Ltd.- Distribution 9. Adani Electricity Mumbai Ltd.- Generation 10. Adani Electricity Mumbai Ltd. -Transmission 11. Adani Electricity Mumbai Ltd.-Distribution 12. Indian Railways 13. Mindspace Business Parks Pvt. Ltd. 14. Gigaplex Estate Pvt. Ltd. Appearance (All Representatives) 1. Maharashtra State Electricity Transmission Co. Ltd. …… Shri Sanjay Taksande 2. Maharashtra State Electricity Distribution Co. Ltd. …….Shri Paresh Bhagwat 3. BEST Undertaking …….Shri N.N. Chaugule 4. Maharashtra State Load Dispatch Centre …… Shri S.V. Jaltare 5. State Transmission Utility …….Shri S.V. Jewalikar 6. Tata Power Company Ltd.-Generation 7. Tata Power Company Ltd.- Transmission ……Shri Devanand Pallikuth 8. Tata Power Company Ltd.- Distribution 9. Adani Electricity Mumbai Ltd.- Generation ….. Shri Mahesh Bhadoria MERC Order in Case No. 202 of 2020 Page 1 of 24 10. Adani Electricity Mumbai Ltd. -Transmission ..…. Shri Dilip Devasthale 11. Adani Electricity Mumbai Ltd.-Distribution … . Shri Shrikant Yeole …… Shri Kapil Sharma …… Shri Kishor Patil 12. -

Contract No:- BC-01R1

DMRC/MU/LINE-6/BC/01R1 : “Part design and construction of viaduct and 3 elevated stations viz., IIT-Powai, KanjurMarg(W) and Vikrholi (EEH) (excluding Architectural finishing and Pre-engineered steel roof structure of Stations) from chainage 9586.50m to 14358.00 m including ramp for Depot entry uptochainage 14490.60m of Swami Samarth Nagar –JVLR – SEEPZ - KanjurMarg(W) –Vikhroli(EEH) Metro Corridor (Line 6) of Mumbai Metro Rail Project .” Contract No:- BC-01R1 SUMMARY SHEET (Modification in Tender Documents) (ADDENDUM NO-1) S.No. Tender Clause No./ Page- Addendum / Corrigendum Remarks Document Item No. No. Volume-1 NIT 1 NIT Clause 1 & 2 Key dates extended Page 1 & 2 are 1.1.2 replaced with Page 1R & 2R 2 NIT Clause 3 Clause 1.1.3.1 iv is modified. Page 3 is 1.1.3.1 iv replaced with Page 3R 3 NIT Clause 5 Clause 1.1.3.2 A is modified. Page 5 is 1.1.3.2A replaced with Page 5R Volume-3 EMPLOYER’S REQUIREMENT(GENERAL,FUNCTIONAL,DESIGN,CONSTRUCTION,APPENDICES) 4 Clause 20 Clause 2.1.6(p-i) is modified. Page 20 is 2.1.6(p-i) replaced with Employer’s Page 20R Requirement- 5 Functional Clause 27 Clause 2.9.7 is modified. Page 27 is 2.9.7 replaced with Page 27R 6 Employer’s Appendix 63 Appendix 2A is modified Page 63 is Requirement- 2A replaced with Appendices Page 63R Volume -4 Technical Specifications 7 Technical Clause B.7 159 Clause B.7 is modified Page 159 is Specifications Installatio replaced with n Page 159R Volume-6 Bill of Quantities 8 Preamble - Preamble is Modified Preamble is Modified 9 Summary of Summary of schedules A, B & C is Summary of Schedule ‘Á’ , Modified schedules C is Bill of ‘B’ & ‘Ç’ Modified - Quantities 10 Schedule ‘Ç’ - Schedule C is Modified Schedule C is Modified Contract: DMRC/MU/LINE6/BC/01R1: Part design and construction of viaduct and 3 elevated stations viz. -

Detailed Project Report Extension of Mumbai Metro Line-4 from Kasarvadavali to Gaimukh

DETAILED PROJECT REPORT EXTENSION OF MUMBAI METRO LINE-4 FROM KASARVADAVALI TO GAIMUKH MUMBAI METROPOLITAN REGION DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (MMRDA) Prepared By DELHI METRO RAIL CORPORATION LTD. October, 2017 DETAILED PROJECT REPORT EXTENSION OF MUMBAI METRO LINE-4 FROM KASARVADAVALI TO GAIMUKH MUMBAI METROPOLITAN REGION DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (MMRDA) Prepared By DELHI METRO RAIL CORPORATION LTD. October, 2017 Contents Pages Abbreviations i-iii Salient Features 1-3 Executive Summary 4-40 Chapter 1 Introduction 41-49 Chapter 2 Traffic Demand Forecast 50-61 Chapter 3 System Design 62-100 Chapter 4 Civil Engineering 101-137 Chapter 5 Station Planning 138-153 Chapter 6 Train Operation Plan 154-168 Chapter 7 Maintenance Depot 169-187 Chapter 8 Power Supply Arrangements 188-203 Chapter 9 Environment and Social Impact 204-264 Assessment Chapter 10 Multi Model Traffic Integration 265-267 Chapter 11 Friendly Features for Differently Abled 268-287 Chapter 12 Security Measures for a Metro System 288-291 Chapter 13 Disaster Management Measures 292-297 Chapter 14 Cost Estimates 298-304 Chapter 15 Financing Options, Fare Structure and 305-316 Financial Viability Chapter 16 Economical Appraisal 317-326 Chapter 17 Implementation 327-336 Chapter 18 Conclusions and Recommendations 337-338 Appendix 339-340 DPR for Extension of Mumbai Metro Line-4 from Kasarvadavali to Gaimukh October 2017 Salient Features 1 Gauge 2 Route Length 3 Number of Stations 4 Traffic Projection 5 Train Operation 6 Speed 7 Traction Power Supply 8 Rolling Stock 9 Maintenance Facilities -

And the English Imperative: a Study of Language Ideologies and Literacy Practices at an Orphanage and Village School in Suburban New Delhi

“Globalization” and the English Imperative: A Study of Language Ideologies and Literacy Practices at an Orphanage and Village School in Suburban New Delhi by Usree Bhattacharya A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Prof. Laura Sterponi, Chair Prof. Claire Kramsch Prof. Robin Lakoff Fall 2013 “Globalization” and the English Imperative: A Study of Language Ideologies and Literacy Practices at an Orphanage and Village School in Suburban New Delhi Copyright © 2013 By Usree Bhattacharya Abstract “Globalization” and the English Imperative: A Study of Language Ideologies and Literacy Practices at an Orphanage and Village School in Suburban New Delhi by Usree Bhattacharya Doctor of Philosophy in Education University of California, Berkeley Professor Laura Sterponi, Chair This dissertation is a study of English language and literacy in the multilingual Indian context, unfolding along two analytic planes: the first examines institutional discourses about English learning across India and how they are motivated and informed by the dominant theme of “globalization,” and the second investigates how local language ideologies and literacy practices correspond to these discourses. An ethnographic case study, it spans across four years. The setting is a microcosm of India’s own complex multilingualism. The focal children speak Bengali or Bihari as a first language; Hindi as a second language; attend an English-medium village school; and participate daily in Sanskrit prayers. Within this context, I show how the institutional discursive framing of English as a prerequisite for socio- economic mobility, helps produce, reproduce, and exacerbate inequalities within the world’s second largest educational system. -

JICA Experts Study for the Operations and Maintenance Structure Of

Republic of India Mumbai Metro Rail Corporation JICA Experts Study for the Operations and Maintenance Structure of Mumbai Metro Line 3 Project in India Final Report October 2015 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Japan International Consultants for Transportation Co., Ltd. PADECO Co., Ltd. 4R Metro Development Co., Ltd JR 15-046 Table of Contents Chapter 1 General issues for the management of urban railways .............................. 1 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Management of urban railways ........................................................................................ 4 1.3 Construction of urban railways ...................................................................................... 12 1.4 Governing Structure ........................................................................................................ 17 1.5 Business Model ................................................................................................................. 21 Chapter 2 Present situation in metro projects ............................................................ 23 2.1 General .............................................................................................................................. 23 2.2 Metro projects in the world ............................................................................................. 23 2.3 Summary........................................................................................................................ -

M. A.II Public Economics Title English.P65

HI SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY, KOLHAPUR CENTRE FOR DISTANCE EDUCATION Public Economics (Group C - Compulsory Paper-V) For M. A. Part-II KJ Copyright © Registrar, Shivaji University, Kolhapur. (Maharashtra) First Edition 2013 Prescribed for M. A. Part-II All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form by mimeography or any other means without permission in writing from the Shivaji University, Kolhapur (MS) Copies : 200 Published by: Dr. D. V. Muley Registrar, Shivaji University, Kolhapur-416 004. Printed by : Superintendent, Shivaji University Press, Kolhapur-416 004 ISBN-978-81-8486-474-8 # Further information about the Centre for Distance Education & Shivaji University may be obtained from the University Office at Vidyanagar, Kolhapur-416 004, India. # This material has been produced with the developmental grant from DEC-IGNOU, New Delhi. (ii) Centre for Distance Education Shivaji University, Kolhapur I ADVISORY COMMITTEE I Prof. (Dr.) N. J. Pawar Prof. (Dr.) K. S. Rangappa Vice-Chancellor, Hon. Vice-Chancellor, Karnataka State Open Shivaji University, Kolhapur University, Mansagangotri, Mysore Prof. (Dr.) R. Krishna Kumar Prof. V. Venkaih Hon. Vice-Chancellor, Yashwantrao Chavan Director, Academic Dr. B. R. Ambedkar Maharashtra Open University, Dnyangangotri, Open University Rd. No. 46, Jubilee Hill, Near Gangapur Dam, Nasik Hyderabad-33 Andhrapradesh Dr. A. P. Gavali Dr. J. S. Patil Dean, Faculty of Arts, Dean, Faculty of Social Sciences, Shivaji University, Kolhapur Shivaji University, Kolhapur Dr. C. J. Khilare Dr. R. G. Phadatare Dean, Faculty of Science, Dean, Faculty of Commerce, Shivaji University, Kolhapur Shivaji University, Kolhapur Prof. (Dr.) A. B. Rajge Prof. (Dr.) D. V. Muley Director, B.C.U.D., Registrar, Shivaji University, Kolhapur Shivaji University, Kolhapur Dr. -

Details of Shareholders' Dividend Outstanding for 7

NELCO LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS WHOSE DIVIDEND IS OUTSTANDING FOR 7 CONSECUTIVE YEARS ( 2013 & 2019 ) Total Outstanding SrNo Folio No/DPID ClientID 1st Holder Name 1st Joint Holder 2nd Joint Holder Add Line 1 Add Line 2 Add Line 3 Add Line 4 Add City Add Pincode Current Holding Amount_24JAN13 Amount_26JUL19 Amount Rs. 1 NED0000022 DENIS J MATHIAS C/O MR E J MATHIAS NO 1 WALTON ROAD BANGALORE 0 100 200.00 50.00 150.00 2 NEH0000053 HEMANT PREMJI THACKER Mr Premji Valji Thacker 7/34 SHYAM NIVAS B DESAI ROAD 0 150 300.00 75.00 225.00 3 NEJ0000046 JAYENDRAKUMAR KUNJBIHARILAL VYAS MAHATMA GANDHI ROAD DOHAD 0 50 100.00 25.00 75.00 4 NEK0000107 K T NITHYANANDAN PEOPLE S RADIO SERVICE TELLICHERRY 0 40 80.00 20.00 60.00 5 NEP0000016 PHIROZE DARASHAW ELAVIA STATION ROAD RAJPIPLA 0 10 20.00 5.00 15.00 6 NES0000132 S M S INVESTMENT CORPN PVT LTD BRANCH OFFICE RAJMAHAL PALACE JAIPUR 0 100 200.00 50.00 150.00 7 NEI0000004 TATA INVESTMENT CORPORATION LIMITED EWART HOUSE BRUCE STREET FORT BOMBAY 1 350 700.00 175.00 525.00 8 NEA0010207 AADITYA GARG C/O ANIL KUMAR GUPTA 164-D KAMLA NAGAR DELHI 110007 50 100.00 25.00 75.00 9 NES0010358 SANCHIT GUPTA C/O ANIL KUMAR GUPTA 164-D KAMLA NAGAR DELHI 110007 50 100.00 25.00 75.00 10 IN30177416703637 SHWETA KAPOOR 12/2 SHAKTI NAGAR DELHI 110007 100 200.00 50.00 150.00 11 IN30046810025744 ANUPMA SUNEJA Sameer Suneja C-5/20 II ND FLOOR SAFDURJUNG DEVELOPMENT AREA NEW DELHI 110016 200 400.00 100.00 300.00 12 NEA0000117 ATARKALI JAIN S 322 PANCHSHILA PARK NEW DELHI 110017 110017 50 100.00 25.00 75.00 13 NER0011096 -

Dosti Greater Thane Brochure

THE CITY OF HAPPINESS CITY OF HAPPINESS Site Address: Dosti Greater Thane, Near SS Hospital, Kalher Junction 421 302. T: +91 86577 03367 Corp. Address: Adrika Developers Pvt. Ltd., Lawrence & Mayo House, 1st Floor, 276, Dr. D. N. Road, Fort, Mumbai - 400 001 • www.dostirealty.com Dosti Greater Thane - Phase 1 project is registered under MahaRERA No. P51700024923 and is available on website - https://maharerait.mahaonline.gov.in under registered projects Disclosures: (1) The artist’s impressions and stock image are used for representation purpose only. (2) Furniture, fittings and fixtures as shown/displayed in the show flat are for the purpose of showcasing only and do not form part of actual standard amenities to be provided in the flat. The flats offered for sale are unfurnished and all the amenities proposed to be provided in the flat shall be incorporated in the Agreement for Sale. (3) The plans are tentative in nature and proposed but not yet sanctioned. The plans, when sanctioned, may vary from the plans shown herein. (4) Dosti Club Novo is a Private Club House. It may not be ready and available for use and enjoyment along with the completion of Dosti Greater Thane - Phase 1 as its construction may get completed at a later date. The right to admission, use and enjoyment of all or any of the facilities/amenities in the Dosti Club Novo is reserved by the Promoters and shall be subject to payment of such admission fees, annual charges and compliance of terms and conditions as may be specified from time to time by the Promoters. -

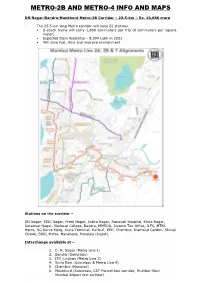

Metro-2B and Metro-4 Info and Maps

METRO-2B AND METRO-4 INFO AND MAPS DN Nagar-Bandra-Mankhurd Metro-2B Corridor – 23.5-km – Rs. 10,986 crore · The 23.5-km long Metro corridor will have 22 stations • 6-coach trains will carry 1,800 commuters per trip (8 commuters per square meter) • Expected Daily Ridership – 8.099 Lakh in 2021 • Will save fuel, time and improve environment Stations on the corridor – DN Nagar, ESIC Nagar, Prem Nagar, Indira Nagar, Nanavati Hospital, Khira Nagar, Saraswat Nagar, National College, Bandra, MMRDA, Income Tax Office, ILFS, MTNL Metro, SG Barve Marg, Kurla Terminal, Kurla-E, EEH, Chembur, Diamond Garden, Shivaji Chowk, BSNL Metro, Mankhurd, Mandala (Depot). Interchange available at – 1. D. N. Nagar (Metro Line 1) 2. Bandra (Suburban) 3. ITO junction (Metro Line 3) 4. Kurla East (Suburban & Metro Line 4) 5. Chembur (Monorail) 6. Mankhurd (Suburban, CST-Panvel fast corridor, Mumbai–Navi Mumbai Airport fast corridor) Wadala-Ghatkopar-Thane -Kasarvadavli Metro-4 corridor – 32-km – Rs. 14,549 crore • The 32.32-km long Metro corridor will have 32 stations • 6-coach trains will carry 1,800 commuters per trip (8 commuters per square meter) • Expected Daily Ridership – 8.7 Lakh in 2021-22 • Will save fuel, time and improve environment Stations on the Corridor – Wadala Depot, Bhakti Park Metro, Anik Nagar Bus Depot, Suman Nagar, Siddharth Colony, Amar Mahal Junction, Garodia Nagar, Pant Nagar, Laxmi Nagar, Shreyas Cinema, Godrej Company, Vikhroli Metro, Surya Nagar, Gandhi Nagar, Naval Housing, Bhandup Mahapalika, Bhandup Metro, Shangrila, Sonapur, Mulund Fire Sta tion, Mulund Naka, Teen Haath Naka (Thane), RTO Thane, Mahapalika Marg, Cadbury Junction, Majiwada, Kapurbawdi, Manpada, Tikuji -ni-wadi, Dongri Pada, Vijay Garden, Kasarvadavali with car depot at Owale .