Bulletin Vol 45 No2 2015 V8.Pub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cotton Mills for the Continent

cotton mills_klartext.qxd 30.05.2005 9:11 Uhr Seite 1 Cotton mills for the continent Sidney Stott und der englische Spinnereibau in Münsterland und Twente Sidney Stott en de Engelse spinnerijen in Munsterland en Twente 1 cotton mills_klartext.qxd 30.05.2005 9:11 Uhr Seite 2 Cotton mills for the continent Bildnachweis/Verantwoording Sidney Stott und der englische Spinnereibau in afbeldingen Münsterland und Twente – Sidney Stott en de Engelse spinnerijen in Munsterland en Twente Andreas Oehlke, Rheine: 6, 47, 110, 138 Archiv Manz, Stuttgard: 130, 131, 132l Herausgegeben von/Uitgegeven door Axel Föhl, Rheinisches Amt für Denkmalpflege, Arnold Lassotta, Andreas Oehlke, Siebe Rossel, Brauweiler: 7, 8, 9 Axel Föhl und Manfred Hamm: Industriegeschichte Hermann Josef Stenkamp und Ronald Stenvert des Textils: 119 Westfälisches Industriemuseum, Beltman Architekten en Ingenieurs BV, Enschede: Dortmund 2005 111, 112, 127oben, 128 Fischer: Besteming Semarang: 23u, 25lo Redaktion/Redactie Duncan Gurr and Julian Hunt: The cotton mills of Oldham: 37, 81r Hermann Josef Stenkamp Eduard Westerhoff: 56, 57 Hans-Joachim Isecke, TECCON Ingenieurtechnik, Zugleich Begleitpublikation zur Ausstel- Stuhr: 86 lung/Tevens publicatie bij de tentoonstelling John A. Ledeboer: Spinnerij Oosterveld: 100 des Westfälischen Industriemuseums John Lang: Who was Sir Philip Stott?: 40 Museum Jannink, Enschede: 19, 98 – Textilmuseum Bocholt, Museum voor Industriële Acheologie en Textiel, des Museums Jannink in Enschede Gent: 16oben und des Textilmuseums Rheine Ortschronik (Stadtarchiv) Rüti: 110 Peter Heckhuis, Rheine: 67u, 137 Publikation und Ausstellung ermöglichten/ Privatbesitz: 15, 25u, 26u, 30, 31, 46, 65, 66, 67oben, 83oben, 87oben, 88u, 88r, 90, 92, 125l Publicatie en tentoonstelling werden Rheinisches Industriemuseum, Schauplatz Ratingen: mogelijk gemaakt door 11, 17 Europäische Union Ronald Stenvert: 26r, 39r, 97, 113oben, 113r, 114, 125r, Westfälisches Industriemuseum 126 Kulturforum Rheine Roger N. -

Stockport Archive Service

GB0130 B/NN Stockport Archive Service This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 20423 The National Archives PS/s-R HEW :iILL 1 90? - 1 -1 35 Records deposited v/ith Stoekport—- Public Libraries in Nov.1976. "by Mr, J. Walsh,,General Manager.. 1907-1 959 WAGES 1907-1957* Employment Registration Cards. B/HH/Ij/9 1952. P39 (SREEN Card) - instructions to employers re code cards, B/M/U/9 1953*P8 (Blue Card) instructions to employers re weekly tax deduction cards, B/lTU/k/9 1953. P7 Employers Guide to P.A.Y.E, B/N1./V9 1957- 58. Details of employers and employees national Insurance contributions. B/HiyU/ii 1958- 59* Notices to employer of amended tax code numbers for employees, B/ftfi/2j/9 1956.P15.8, Authority'to refund income tax to new employee. B/iu:/ii/9 nd. (e.1 958) Pij-5* Employer's copies of leaving certificates. 3/m/k/9 nd, (c.1958) P35, List of tax deduction cards AND emergency cards, 3/lTi/k/S 3l*i*l959p Weekly return - wages and production. B/m:/h/9 1958-59. Details of wages deductions * B/WV12 ^ 924.5-1 959. Bet ails of tax deduction. B/tlR/lj/l 0 z/m/k/u (also included is a Pear Mill semi-gusset envelope) B/hu/k/9 1912 EXTRACT CP MINUTES (2 copies) Of Director^ Meetings on 26th April, 2Sth April, 1st May, 6th May, 9th May, 15th May, 16th May and 17th May relating to Mr. -

AIA Bulletin 19-2 1992

ASSOCIATION FOR INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY Volume 19 Number 2 1992 CONFERRING IN DUDLEY by Ron Moss on the Biack Country chain- trial processes Leisurely discussion conttnued makrng industry by Roger Dodsworth on glass late into the nrght in the Polytechnic bar The AlA s annual conference for 1991 at manufacturing rn the Stourbridge area, and by Some of the more formal events of the Dudley, was the best attended ever and one of Mike Glasson on the Walsall leather trades conference were a reception hosted by Dudley the most successful The nratn conference Informatrve and enjoyable excursions to local lvletropoliian Borough Council followed by an nrnn/2mmc ni 13-1\ SFnlember followed on sites were made on the Saturday afternoon excellent Conference Dinner and the annual from a pre-conference programme of visits and The conference divided into three parties, to AIA award presentations as reported in the last lectures introducing members to the locality ol visit Mushroom Green and the Cradley chain issue of the Bulletin The Annual Generai the conference, as described by Martlyn Palmer marrng distrrct. the Stuarl Crystal Glass Meeting ol the AIA was held on the Sunday and Peter Neaverson on page 2 The con- Museum, Wordsley Locks and Cobbs engine morning, at which the officers and Counctl of f erence was hosted by the Black Country house and the Walsall Leather Centre and the the Association were elected Two addittons to Society and the Black Country Museum and National Lock Museum at Wrllenhall Council were notified in the last Bulletin Iwo organised by John Crompton and Carol Whtt- Members' contnbutions sessions are always new Honorary Vice-Presidents were also elec- taker with assistance from Janet Graham John an enthusiastrcally supported element of con- ted: John Hume and Angus Buchanan In Fletcher and a posse of expert members of ference programmes grvrng members a commenting on Professor Buchanan s eiectton, the Black Country Society Accommodatton chance to learn about work others have been the President, David Alderton. -

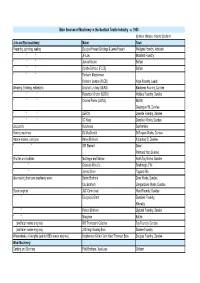

Sources of Machinery in the Scottish Textile Industry - C

Main Sources of Machinery in the Scottish Textile Industry - c. 1950 By Mark Watson, Historic Scotland Jute and Flax machinery Maker Town Preparing, spinning, reeling Douglas Fraser (Giddings & Lewis Fraser) Wellgate Foundry, Arbroath “ “ “ JF Low Monifieth Foundry “ “ “ James Mackie Belfast “ “ “ Combe Barbour (FLCB) Belfast “ “ “ Fairbairn Macpherson Fairbairn Lawson (FLCB) Hope Foundry, Leeds Weaving, finishing, millwrights Urquhart Lindsay (ULRO) Blackness Foundry, Dundee “ “ “ Robertson Orchar (ULRO) Wallace Foundry, Dundee “ “ “ Charles Parker (ULRO) Mid St/ Clepington Rd, Dundee “ “ “ LEFCO Lawside Foundry, Dundee “ “ “ TC Keay Densfield Works, Dundee Jacquards Hutcheson Dunfermline Sewing machines DJ MacDonald St Roques Works, Dundee Hackle-makers; card pins Halley Brothers N Lindsay St, Dundee “ “ WR Stewart Dens/ Panmure Yard Dundee Shuttles and bobbins McGregor and Balfour North Tay Works, Dundee “ “ Gateside Mills Co, Strathmiglo, Fife “ “ James Stiven Tayport, Fife Also making their own machinery were: Baxter Brothers Dens Works, Dundee Cox Brothers Camperdown Works, Dundee Steam engines J&C Carmichael Ward Foundry, Dundee “ “ Douglas & Grant Dunnikier Foundry, Kirkcaldy “ “ Pearce Brothers Lilybank Foundry, Dundee “ “ Musgrave Bolton (and later marine engines) WB Thompson/ Caledon Tay Foundry, Dundee (and later marine engines) J Stirling/ Gourlay Bros Dundee Foundry Waterwheels, millwrights (and in 1890s steam engines) Umpherston & Kerr/ John Kerr/ Thomson Bros Douglas Foundry, Dundee Wool Machinery Carding and Spinning Platt Brothers / Asa Lees Oldham Haigh, various Yorkshire Weaving Hattersley Keighley Dobcross Yorkshire Finishing Whiteley Yorkshire Thomas Aimer/ Galashiels Aimers Mclean Cotton Machinery Spinning fine counts Dobson & Barlow Bolton Brooks & Doxey Manchester Spinning medium counts Platt Brothers Oldham weaving various: eg Hall, Howard & Bullough Lancashire Weaving and millwrights Anderston Foundry Co Glasgow Winding, twisting, croppers JT Boyd Glasgow Lace Leavers Nottingham. -

The North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts Owes Its Existence to the Combined Liberality of the United States Govern- Ment and of R

THE NORTH CAROLINA COLLEGE OF Agriculture and Mechanic Arts WEST RALEIGH 1909-1910 RALEIGH EDWARDS & BROUGHTON PRINTING 00.,STATE PRINTERSAND BINDERB 1910 CALENDAR JANUARY, 1910. FEBRUARY, 1910. MARCH, 1910. 1 2 - s M T w T F s s M T 1 W T 11 F s s M T W T 1 F 1—~ .- ._ .2 -2 .- .. 1 .- -_ 1 2 3 4 5 _- .. 1 2 31 41 5 92 103 114 125 186 147 1 158 136 147 158 169 1 1710 1811 1912 136 147 158 169 1710 1 1811 1 1912 2316 2417 2518 2619 2720 2821 1 2922 2720 2821 22.. 23.. 1 24_. 25_. 26.. 2027 2821 2922 3023 3124 11 25.. 1...1 26 _30 31 .-1-- 1 -- .. -. .2 ._ .. .. 1.. 7 .. __ _- .. .- _. ..,-_1__' 1 APRIL, 1910 MAY, 1910 JUNE, 1910. -. .. .. .2 ..1 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 ._ -. _- 1 2 3 4 103 114 125 136 147 1 158 169 1 158 169 1710 1811 1912 1 2013 2114 125 1 136 147 158 169 1710 1811 2417 18 19 20 21 1 22 23 : 22 23 24 25 26 1 27 28 19 1 20 21 22 23 24 25 25 26 27 28 1,1 29 307 1 29 30 31 -- 2- 1. -- 22 26 1; 27 28 29 30 1 .. -- JULY, 1910 AUGUST, 1910. SEPTEMBER, 1910. .. .. .. _- -. 1 2 .. 1 211 3 1 4 5 6 ..1--1 .2 _- 1 2 3 103 114 125 136 147 158 169 147 158 169110111213t 17 18 19 20 114151 12 136 147 158 1691017 2417 2518 2619 2720 1 2821 1 2922 1 3023 2128 2922 30231241 31 25._ 26. -

Recent Cotton Mill Construction and Engineering

'^f'UCT Recent Cotton Mill Construction AND Engineering Joseph Nasmf LIBRARY ^NSSACHOs^^ 1895 ADVERTISEMENTS. OH every uea«. .n.ion up *° "^^^°'"'f^ MILL GEARING IN At-U ITS BRANCHES, ^^BELTft RORE DRUMS, to any si5e. TURBINES HYDRAULIC MACHINERY Market BARRING ENGINES, the best i n tne UP TO ANY PRESSURE JRIPLE EXPANSION MILl .h irnn WorKs & Pncenix ADVERTISEMENTS. The HIGHEST AWARD fop FEED-WATER HEATER at CHICAGO EXHIBITION has been granted to GREEN'S IlVIF>Rl01tf'EI> I^JLTENT FUEL ECONOMISEH SPECIALLY CONSTRUCTED ON THE FROM Improved Strengthened Patterns J-HT TJSE3 .A.T ALL THE PRINCIPAL STEAM USERS THROUGHOUT THE WORLD. SPECIALITY FOR ELECTRIC LIGHT INSTALLATIONS ORIGINAL INVENTORS, PATENTEES, AND SOLE MAKERS: 2, Exchange Street, MANCHESTER. " " Works : WAKEFIELD. Telegrams : ECONOMISER RECENT COTTON MILL CONSTRUCTION AND ENGINEERING. JOSEPH NASMITH, EDITOR OF THE "TEXTILE RECORDER"; AUTHOR OF "MODERN COTTON SPINNING machinery"' AND "THE STUDENTS' COTTON SPINNING." JOHN HEYWOOD, Deansgate and Ridoefield, Manchesteb. 2, AMEN CORNER, LONDON, E.G. 22, Paradise Street, Liverpool. 33, Bridge Street, Bristol. IX VAN NOSTRAND COMPANY, NEW YORK. ur. n%^ PREFACE. fTlHE following pages are in great part a reproduction of a special article which appeared in the Textile Recorder for May, 1894. It had been represented to the author that there was need of some article from which accurate informa- tion relating to modern methods of mill construction could be obtained. This led to the work being done, and the manner in which a large edition of the Textile Recorder was taken up demonstrated the interest felt in it. No claim is made for originality in the treatment of the subject, the book being avowedly a compilation of facts derived from actual practice. -

SIR CHARLES W. MACARA, BART. Sir Charles W

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Ex Libris C. K. OGDEN SIR CHARLES W. MACARA SIR CHARLES W. MACARA, BART. Sir Charles W. Macara, Bart. A STUDY OF Modern Lancashire BY HASLAM MILLS SECOND EDITION MANCHESTER SHERRATT & HUGHES 1917 CONTENTS. CHAPTER PAGE I. INFLUENCES - i II. VICTORIAN MANCHESTER - - 17 III. THE HOUSE OF BANNERMAN - 35 IV. THE OPERATIVES - - 53 V. MASTERS AND MEN - - 73 VI. THE BROOKLANDS AGREEMENT AND THE INDUSTRIAL COUNCIL - 93 VII. INTERNATIONALISM : INTERNATIONAL COTTON FEDERATION : INTER- NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF AGRICUL- TURE - 125 VIII. WAR : COTTON RESERVE : COTTON AS CONTRABAND: NATIONAL REGISTER 155 "'\ IX. REST IN CHANGE OF WORK : LIFEBOAT SATURDAY, ETC. - - - - 177 APPENDIX PAGE A. The Cotton Industry : A comprehensive Survey from the Earliest Times, A paper prepared, at the request of the Belgian Government, by Sir C. W. Macara, Bart., and delivered at the Ghent Exhibition, 1913 - - 191 ft CONTENTS APPENDIX PAGE B. America : Address on the Opening Day of the International Convention of Cotton Growers, Spinners and Repre- sentatives of the Cotton Exchanges, Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.A., 1907 - 209 President Roosevelt : Correspondence, etc. - 218 C. Egypt : Address on the Opening Day of the International Cotton Confer- ence, Alexandria, 1912 - - 222 The Development of the Sudan : Deputa- tion of the British Cotton Growing Association to the Prime Minister (1913) : British Government re- quested to guarantee a loan of 3,000,000 - - 233 Reception by Viscount Kitchener at Cairo - - 239 Text of Illuminated Address - - 245 D. India : Deputation of the International Cotton Federation to the Most Hon. the Marquess of Crewe, Secretary of State for India - - 249 E. -

The North Carolina College Agriculture and Mechanic

THE NORTH CAROLINA COLLEGE AGRICULTURE AND MECHANIC ARTS, WEST RALEIGH. 1908-1909. RALEIGH: E. M. UZZELL & 00., STATE PRINTERS AND BINDERS. 1909. CALENDAR. 1909- 19.1.0. JANUARY. JULY. JANUARY. FEBRUARY. AUGUST. FEBRUARY. 234561234567__-_12J3 1e9101112138910111213146789‘1017 18 19 2o 15 1e 17 18 19 2o 21 13 14 15 16 17 23__ 24__ 25__ -_26 27__ 2922 so23 3124 25-_ 26-- 27__ 28__ 2720 2821 22__ 23;242- 27 28 29 30 —_ 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 24 25 26 27 28 _, — 7I" —— -— 31 _— —» '7 —— —— —— __ —— .. —— —— MAY NOVEMBER MAY —— —— _, —_ 1 _— 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 15 16 17 18 19 [2 13 1415 16 1'7 18 12 13 14 15‘ 29 30 —~ —- —— 26 27 28 29 30 31 —— 26 2’7 28 29 TABLE OF CONTENTS. College Calendar 4 Board of Trustees............................................ 5 Faculty ..................................................... 6 North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station............ S Military Organization .................................... 9 General Information ......................................... 12 Requisites for Admission.................................. 20 Entrance Examinations 21 Expense ................................................. 22 Courses of Instruction............................ l 26 School of Agriculture....................I..................... 27 Four-year Course ........................................ 29 One-year Course ......................................... 46 Winter Short Courses: One—week Cotton Course.............................. 48 Seven—weeks Course .................................v. 48 Engineering Courses -

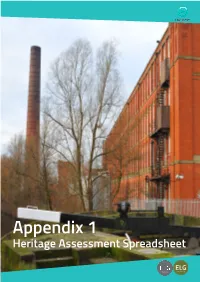

Appendix 1 Heritage Assessment Spreadsheet

Appendix 1 Heritage Assessment Spreadsheet Heritage Town Planning LOCATION Extant Landscape Name in 1992 pub. gaz. Other names Condition Heritage Significance Sense of Place Overall Score Y / N Value S e Architectural / Communal Sig v Sense of Historical Interest Score Score Significance Score Setting Score Experience Score Score n aesthetic Interest Value Place Ranking s e Red brick construction six storey, steel and Built prior to concrete internal 1914. Platts structure. Large Commercial Ace mill Whitegate machinery, rectangular setting, backs contributes to Associations Lane, Urmson & windows with Gorse Mill onto Costco car group value with with former use Ace Mill Y Chadderton, Good High Thompson engine. 3 concrete 2 2.5 3 4 2 2.8 No. 2 park. Group value Gorse Mill. Alone and group value Oldham, OL9 Used for aircraft surrounds. Corner with Gorse and it contributes very with Gorse Mill. 9RJ manufacture 1914- pilasters, Ram Mills. little. 18, first spun restrained cotton 1919. embellishments, tower, engine house and rope drive. red brick Platt Brothers construction. Four macchine storey in height, makers,blowing multi ridge roof, room machinery stone band to each Industrial setting. Limited department. floor. Tower to Hartford Old Group value with Industrial area associations Adelaide Mill GouldY Street, Oldham, OL1 3PW Medium Associative value 4 south-east corner. 3 3.5 2 1 1 2.8 Works Hartford Old with activity. with former with J Stott. Part Engine shed Works. use. of Hartford Old detached to south. Works. Moved to Of two storey Hartford New height with Works in 1844. pitched roof. Two storey Old Works Brick construction Located beside a Within four storey and former canal, now commercial/indus Albert long in formwith infilled. -

Final Thesis.Pdf

Civic and municipal leadership: a study of three northern towns between 1832 and 1867 Michael Joseph Brennan Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds, School of History March 2013 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been submitted on the understanding that it is the copyright material and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2013 The University of Leeds Michael Joseph Brennan iii Acknowledgements This thesis has its origin in an MA in Local Regional History undertaken at the University of Leeds in 1988, but it would never have reached this state without the guidance, support and knowledge of my supervisor, Professor Malcolm Chase of the University of Leeds. I owe him a great debt for helping me to turn my hazy ideas into a coherent piece of work, and reminding me how to study History again, after years spent in education. My thanks are also due to the staff of the School of History and of the University Library for their help and guidance. I have visited the following archive centres: West Yorkshire Archive Services at Halifax and Wakefield, Local Studies Centres at Oldham and Rochdale and The National Archive at Kew. Wherever I have gone, I have been helped with kindness, humour and outstanding professionalism for which I am extremely grateful. I am delighted that my friend and colleague Alastair Linden was able to help with ideas and proof reading. -

10Th Anniversary Edition

10th Anniversary Edition Stamford Park Early 1900s Issue 5 Free Printed by GB Winstonmead Print, Loughborough, Leicestershire LE11 1LE CONTENTS Tameside Local History Forum – 10 Years On 1 Heritage Open Days in Mossley 2009 3 Thomas Averill Dukinfield III 5 Spirit of Ashton-under-Lyne 6 As We Say Goodbye to another Landmark in Tameside 7 The Public Catalogue Foundation 8 Friends of Ashton Parish Church 9 Unveiling Ceremony of the Red Hall Datestone AD 1876 11 Broadbottom History: Stories upon Stories 12 The Fletcher Family 13 Some Account of the Family of the Armitages 17 New Beginnings: The new Centre for Applied Archaeology 20 Spotlight on the Church of St Thomas the Apostle, Hyde 23 Murder at the Strangler’s Arms 24 The HV Morton Appreciation Society 25 Tameside’s Forgotten Canal 27 Hyde Chapel Organ Case Restoration 2008 29 Dukinfield Built: Huge order off to Ireland fifty-five years a go 31 Polish Camp at Audenshaw 32 Huddersfield Narrow Canal 33 Directory 34 Huddersfield Narrow Canal 36 James Bevan Hat Manufacturer of Denton and Stockport 37 Chemicals and Plastics, and the Sterling Group 40 Waterworks; Celebrating the Work of John Frederick La Trobe Bateman 41 John Owen, 1815-1902, Old Mortality 43 Schooldays before and during the Second World War 45 “Who is this Ruddy Kipling?” 46 East Cheshire Union of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches 49 Millbrook in the 1920s 53 Extracts from the Old Chapel, Dukinfield Burial Registers 56 Memories of Hyde Theatre Royal 57 Medlock and Tame Valley Conservation Association 58 Thomas Keighley – Albion Church Organist 59 The Bright Shop, Park Bridge 62 Lancashire’s Romantic Radical 64 Casualties of War 66 Memories Inspired by the ‘Flying Dentist’ 68 Jack Patterson 1926-2009 Obituary plus Anniversaries in Tameside 70 The views expressed in articles and reviews are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Tameside Local History Forum. -

Textile Mills and Their Landscapes Therefore Depends on Promotion of Active Re-Use

The International Context for Textile Sites This comparative study was compiled by the Textile Special Interest Section of the International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage (TICCIH). The text was discussed at meetings of the section in London, UK, in 2000, Barcelona, Spain, in 2001, in Euskirchen, Germany, in 2003 and Sedan, France, in 2007.1 The draft list was also displayed on the TICCIH website, was presented to the Association for Industrial Archaeology Conference in 2002 to the Society for Industrial Archeology in 2004 and to TICCIH in Terni in 2006. Contents 1. Preface 2. Universal Significance of Textile History 3. Definition, authenticity and protection of a textile site. 4 Typology of the functional elements of a textile mill 5. List of Known Textile Sites of International Significance 1. Preface This list is one of a series of industry-by-industry lists offered to ICOMOS for use in providing guidance to the World Heritage Committee as to sites that could be considered of international significance. This is not a sum of proposals from individual countries, neither does it make any formal nominations for World Heritage Site inscription: States Parties do that. A thematic study presents examples, and omission here does not rule out future consideration. The study attempts to arrive at a consensus of expert opinion on what might make sites, monuments and landscapes significant. This follows the Global Strategy for a representative, balanced and credible world heritage list. Industrial sites are among the types of international monuments that are at present considered to be under-represented on the World Heritage List.