Textile Mills and Their Landscapes Therefore Depends on Promotion of Active Re-Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study on Improving the Production Rate by Rapier Looms in Textile Industry Aby Chummar, Soni Kuriakose, George Mathew

ISSN: 2277-3754 ISO 9001:2008 Certified International Journal of Engineering and Innovative Technology (IJEIT) Volume 2, Issue 7, January 2013 Study on Improving the Production Rate by Rapier Looms in Textile Industry Aby Chummar, Soni Kuriakose, George Mathew the company. It is mainly manufactured by the shuttle looms. Abstract— In India the textile industry is growing very fast. Conventional shuttle looms are mainly used during the Most of the earlier established textile industries are using weaving process in the industry. All these shuttle looms are conventional shuttle looms for the production of the cloth. But the too old. In these present conventional shuttle looms, it is advancement in the technology made the textile industry more competitive. The effective usage of the new methods of the necessary to pass a shuttle weighing around half a kilogram weaving technology, which is more energy efficient, makes the through the warp shed to insert a length of weft yarn which production more economical. It is found out that the usage of the weighs only few grams. The shuttle has to be accelerated conventional looms badly affects the cloth production. This study rapidly at the starting of picking cycle and also to be focuses on identifying the problems associated with the low decelerated, stopped abruptly at the opposite end. This production by the shuttle loom and suggesting suitable methods process creates heavy noise and shock and consumes by which these problems can be reduced. considerable energy. Beat-up is done by slay motion which again weighs a few hundred kilograms. The wear life of the Index Terms—Greige Fabric Picks, Rapier Loom, Shuttle Loom. -

History of Weaving

A Woven World Teaching Youth Diversity through Weaving Joanne Roueche, CFCS USU Extension, Davis County History of Weaving •Archaeologists believe that basket weaving and weaving were the earliest crafts •Weaving in Mesopotamia in Turkey dates back as far as 7000 to 8000 BC •Sealed tombs in Egypt have evidence of fabrics dating back as far as 5000 BC •Evidence of a weavers workshop found in an Egyptian tomb 19th Century BC •Ancient fabrics from the Hebrew world date back as early as 3000 BC History of Weaving (continued) •China – the discovery of silk in the 27th Century BCE •Swiss Lake Dwellers – woven linen scraps 5000 BCE •Early Peruvian textiles and weaving tools dating back to 5800 BCE •The Zapotecs were weaving in Oaxaca as early as 500 BC Weavers From Around the World Master weaver Jose Cotacachi in his studio in Peguche, Ecuador. Jose’s studio is about two and a half miles from Otavalo. Weavers making and selling their fabrics at the Saturday market in Otavalo, Ecuador. This tiny cottage on the small island of Mederia, Portugal is filled with spinning and weaving. Weavers selling their fabrics at an open market in Egypt. The painting depicts making linen cloth, spinning and warping a loom. (Painting in the Royal Ontario Museum.) Malaysian weavers making traditional Songket – fabric woven with gold or silver weft threads. A local Tarahumara Indian weaving on a small backstrap loom at the train station in Los Mochis. Weavers In Our Neighborhood George Aposhian learned Armenian pile carpets from his father and grandparents who immigrated to Salt Lake City in the early 1900’s. -

Viimeinen Päivitys 8

Versio 20.10.2012 (222 siv.). HÖYRY-, TEOLLISUUS- JA LIIKENNEHISTORIAA MAAILMALLA. INDUSTRIAL AND TRANSPORTATION HERITAGE IN THE WORLD. (http://www.steamengine.fi/) Suomen Höyrykoneyhdistys ry. The Steam Engine Society of Finland. © Erkki Härö [email protected] Sisältöryhmitys: Index: 1.A. Höyry-yhdistykset, verkostot. Societies, Associations, Networks related to the Steam Heritage. 1.B. Höyrymuseot. Steam Museums. 2. Teollisuusperinneyhdistykset ja verkostot. Industrial Heritage Associations and Networks. 3. Laajat teollisuusmuseot, tiedekeskukset. Main Industrial Museums, Science Centres. 4. Energiantuotanto, voimalat. Energy, Power Stations. 5.A. Paperi ja pahvi. Yhdistykset ja verkostot. Paper and Cardboard History. Associations and Networks. 5.B. Paperi ja pahvi. Museot. Paper and Cardboard. Museums. 6. Puusepänteollisuus, sahat ja uitto jne. Sawmills, Timber Floating, Woodworking, Carpentry etc. 7.A. Metalliruukit, metalliteollisuus. Yhdistykset ja verkostot. Ironworks, Metallurgy. Associations and Networks. 7.B. Ruukki- ja metalliteollisuusmuseot. Ironworks, Metallurgy. Museums. 1 8. Konepajateollisuus, koneet. Yhdistykset ja museot. Mechanical Works, Machinery. Associations and Museums. 9.A. Kaivokset ja louhokset (metallit, savi, kivi, kalkki). Yhdistykset ja verkostot. Mining, Quarrying, Peat etc. Associations and Networks. 9.B. Kaivosmuseot. Mining Museums. 10. Tiiliteollisuus. Brick Industry. 11. Lasiteollisuus, keramiikka. Glass, Clayware etc. 12.A. Tekstiiliteollisuus, nahka. Verkostot. Textile Industry, Leather. Networks. -

The History of Dunedin Income Growth Investment Trust

The History of Dunedin Income Growth Investment Trust PLC The first investment trust launched in Scotland, 1873 – 2018 Dunedin Income Growth Trust Investment Income Dunedin Foreword 1873 – 2018 This booklet, written for us by John Newlands, It is a particular pleasure for me, as Chairman of DIGIT describes the history of Dunedin Income Growth and as former employee of Robert Fleming & Co to be Investment Trust PLC, from its formation in Dundee able to write a foreword to this history. It was Robert in February 1873 through to the present day. Fleming’s vision that established the trust. The history Launched as The Scottish American Investment Trust, of the trust and its role in making professional “DIGIT”, as the Company is often known, was the first investment accessible is as relevant today as it investment trust formed in Scotland and has been was in the 1870s when the original prospectus was operating continuously for the last 145 years. published. I hope you will find this story of Scottish enterprise, endeavour and vision, and of investment Notwithstanding the Company’s long life, and the way over the past 145 years interesting and informative. in which it has evolved over the decades, the same The Board of DIGIT today are delighted that the ethos of investing in a diversified portfolio of high trust’s history has been told as we approach the quality income-producing securities has prevailed 150th anniversary of the trust’s formation. since the first day. Today, while DIGIT invests predominantly in UK listed companies, we, its board and managers, maintain a keen global perspective, given that a significant proportion of the Company’s revenues are generated from outside of the UK and that many of the companies in which we invest have very little exposure to the domestic economy. -

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

Fulled Wool Scarves Multiple Projects on the Same Threading

Fulled Wool Scarves multiple projects on the same threading MADELYN VAN DER HOOGT Choose from a fabulous array of colors and make lots of scarves for quick and easy holiday gifts. Change weft colors for different looks on the same warp—or change the colors of the warp, too! Simply tie a new warp onto the one you’ve just finished. The setts of both the warp and the weft in this project are very open to allow maximum fulling to take place during wet finishing. The result is a wonderfully soft, thick, cuddly, warm winter scarf. hese two scarves were woven on dif- secure them in front of the reed. ferent warps, both of Harrisville Then, taking the first end of the old T Shetland, one in Garnet, the other warp and the first end of the new warp on in Peacock. Both yarns are somewhat one side (right side if you are right hand- “heathered” (flecks of other colors are spun ed, left side if you are left-handed), tie into the yarn), a quality that makes them them together in an overhand knot. Re- work well with a variety of weft colors. peat with the next end from each warp and You can choose to weave many scarves on continue until all ends are tied. The knots one very long warp or even tie on new do not have to be exactly at the same point warps to change scarf colors completely. for every tie. Especially with wool, small Whatever you choose, you’ll find the tension differences between the threads weaving easy and fun. -

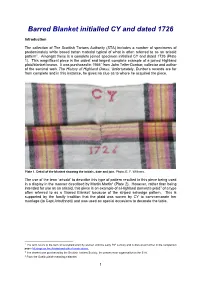

Barred Blanket Initialled CY and Dated 1726

Barred Blanket initialled CY and dated 1726 Introduction The collection of The Scottish Tartans Authority (STA) includes a number of specimens of predominately white based tartan material typical of what is often referred to as an arisaid pattern1. Amongst these is a complete joined specimen initialled CY and dated 1726 (Plate 1). This magnificent piece is the oldest and largest complete example of a joined Highland plaid/blanket known. It was purchased in 19662 from John Telfer Dunbar, collector and author of the seminal work The History of Highland Dressi. Unfortunately, Dunbar’s records are far from complete and in this instance, he gives no clue as to where he acquired the piece. Plate 1. Detail of the blanket showing the initials, date and join. Photo: E. F. Williams. The use of the term ‘arisaid’ to describe this type of pattern resulted in this piece being used in a display in the manner described by Martin Martinii (Plate 2). However, rather than being intended for use as an arisaid, this piece is an example of a Highland domestic plaid3 of a type often referred to as a ‘Barred Blanket’ because of the striped selvedge pattern. This is supported by the family tradition that the plaid was woven by CY to commemorate her marriage (to Capt Arbuthnott) and was used on special occasions to decorate the table. 1 The term refers to the form of over-plaid worn by women until the early 18th century and is discussed further in the companion paper Musings on the Arisaid and other female dress. -

Managing Change in the Historic Environment: Structures

Managing Change in the Historic Environment Engineering Structures October 2010 Key Issues 1. Historic structures and works of civil engineering are often of significant architectural and historic interest in their own right. Listed building consent is required for any works affecting the character of a listed building and planning permission may be required in a conservation area. Scheduled monument consent is always required for works to scheduled monuments. 2. Works to historic engineering structures must be based on a thorough understanding of their design, construction and use of materials. This is likely to require the involvement of structural engineers and others with relevant experience of dealing with such structures. 3. Where remedial or strengthening works are found necessary, they must: • be in sympathy to the way that structure performs; • restore the structural strength and extend its life. 4. Existing materials should be replaced only where essential to structural stability or other safety- related issues, and where the consequences of that intervention are understood. In general, existing material should be retained and augmented, rather than replaced, by new construction where stability or other safety-related issues are of concern. 5. Some structures may not have an obvious alternative use, but should nonetheless be retained to give a sense of place to a development. 6. Planning authorities give advice on the requirement for listed building consent, planning and other permissions. 2 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 This is one of a series of guidance notes on managing change in the historic environment for use by planning authorities and other interested parties. The series explains how to apply the policies contained in the Scottish Historic Environment Policy (2009) (SHEP, PDF 312K) and The Scottish Planning Policy (2010) (SPP, PDF 299K). -

Judges List 2020 For

Suffolk Horse Society Judge List 2020 Turnout Judges - Suffolk Horse Society 2020 Home Telephone Length of Title First Name Surname Address Address 2 Town County Post Code number Telephone Email Addres Area service Mr David Curtis Hale Fen Farm 16 Hale Fen Littleport Ely CB6 1EL 07752066619 [email protected] Cambridgeshire * Mr Owen Garner Hales Farm Green Street Willingham Cambs CB4 5LB 01954 261475 [email protected] Cambridgeshire 2018 * Mr Jonathan Purse Mill Drove Farm Mill Drove Soham Cambs CB7 5HX 01353 720379 07788101305 [email protected] Cambridgeshire 2009 * Mr Malcolm Scurrell 4 Birdbush Park Ludwell Shaftesbury Dorset SP7 9NH 01747 828037 01747 828037 [email protected] Dorset Over 15 years * Mr John Peacock Ashdene, East Hannigfield Road Howe Green Chelmsford Essex CM2 7 TP 07831 384307 [email protected] Essex Over 15 years Mr Paul Mills Barratts Farm, East Lane Dedham Colchester Essex CO7 6BE 01206 323645 [email protected] Essex 2013 Miss Susan Wager Saltcote Hall, Goldhanger Road Heybridge Maldon Essex CM9 7QX 01621 853252 [email protected] Essex Over 15 years Mr Stephen Smith Leylandii Bell Farm Lane, Minster on Sea Isle of Sheppy Kent ME12 4JB 07947 951705 no email address Kent Mr Matthew Burks Roseisle Farm, West Fen Drainside Frithville Boston Lincolnshire PE22 7EU 07506 402779 [email protected] Lincolnshire 2018 * Mr Peter Crockford 201 North Road Gedney Hill Spalding Linconshire PE12 ONU 07867 977864 [email protected] Lincolnshire Over 15 years * Mr Michael L -

Creativech D4.2 Local-Showcases Report

[Local CreativeCH showcases – mobilization and implementation 2] The CreativeCH project is funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. [ LOCAL CREATIVE-CH SHOWCASES – MOBILIZATION & IMPLEMENTATION 2 ] FP7-SCIENCE-IN-SOCIETY-2011-1 Grant Agreement No. 289076 Page| 2 CreativeCH Creative Cooperation in Cultural Heritage Theme SiS.2011.1.3.4-1: Clusters of cities of scientific culture for innovation. Local CreativeCH showcases – mobilization and implementation 2 Deliverable number: D4.2 Dissemination level: Public Delivery date: 31 August 2013 Status: Final Deliverable Authors: Gisela Gonzalo (mNACTEC) Carme Prats (mNACTEC) Guntram Geser (SRFG) Andreas Strasser (SRFG) Sorin Hermon (UVT) Ion Imbrescu (UVT) Franco Niccolucci (PIN) Stephanie Williams (PIN) Sara Trindade (UoC) www.creative-heritage.eu | MFG | mNACTEC | PIN | SRFG | UoC | UVT [ LOCAL CREATIVE-CH SHOWCASES – MOBILIZATION & IMPLEMENTATION 2 ] DELIVERABLE / DOCUMENT INFORMATION: Deliverable nr. / title: D4.2 Local CreativeCH showcases – mobilization and Page| 3 implementation 2 Document title: CreativeCH_D4.2_Local-Showcases_2_final _30082013.pdf Author(s): Gisela Gonzalo (mNACTEC), Carme Prats (mNACTEC), Guntram Geser (SRFG), Andreas Strasser (SRFG), Sorin Hermon (UVT), Ion Imbrescu (UVT), Franco Niccolucci (PIN), Stephanie Williams (PIN), Sara Trindade (UoC) Dissemination level / Public distribution DOCUMENT REVISION HISTORY: Version / Date: Changes / approval: Author / approved by: v0.1 / 23.07.2013 First draft of structure and content G. Gonzalo (mNACTEC) v0.2 / 03.08.2013 Detailed drafts of different sections G. Geser (SRFG) v0.3 / 09.08.2013 Chapter Training & Working with Students S. Trindade (UoC) Full documentation of the implementation of v0.4 / 22.08.2013 Authors of all partners the four showcases G. -

Please Click Here to Download a PDF of the Detailed Listing to Part 3

Portfolio Approx. Earliest No: of Type Cylinder Horse RPM Owner of Other Details Number No: of Date on Engines of Diameter x Power Engine Drawings Drawings Engine Stroke REEL TWENTYNINE Scotland: Ayr 208 12 Sep 1800 1 28” 1/8 x 6’0 30 38 David Dale Cotton Mill. Later acquired by James Finlay & Co. Engine erected at Catrine. Lanark 13 1790 1 S 26” x 6’0 10 John & William Purchased from Folliot Scott & Wilson Co. Forge Mill Engine at Wilson Town, Lanark. 193 14 Sep 1799 1 D 29” x 6’0 32 John Pattison Parchment dated October 1, 1799. John Pattison of Glasgow. Cotton Mill, Glasgow. Payment £797. 106,000lbs. 10 feet high. Purchased by Mr Dunn. 199 7 April 1800 1 D 17” 2/3 x 4’0 10 John Cotton Mill. Brigtown near Bartholomew Glasgow. 202 8 April 1800 1 19” 1/4 x 4’0 12 James Cook & Flax Mill, Glasgow. Co 204 8 May 1800 1 16” x 4’0 8 Robert Brewery, Glasgow. Struthers & Co 209 8 Aug 1800 1 D 28” 1/8 x 6’0 30 Corporation of Flour Mill. Patrick Mills, Bakers Glasgow. 216 3 Feb 1801 1 16” x 4’0 8 50 James Monach Cotton Mill, Glasgow. Originally Matthew Boulton’s Mint Engine. Belonged to Indoe and Galbraith by 1813. 228 9 Aug 1801 1 19” 1/4 x 4’0 12 Tennant Knox Chemical Manufactory, & Co Glasgow. Portfolio Approx. Earliest No: of Type Cylinder Horse RPM Owner of Other Details Number No: of Date on Engines of Diameter x Power Engine Drawings Drawings Engine Stroke Renfrewshire 177 14 Dec 1798 1 D 21” 1/4 x 5’0 16 Underwood Parchment dated January 1, Spinning Co 1799. -

Download Case Study

Visit us at graham.co.uk Murrays’ Mills, Manchester Life Framework Reviving a relic of the past £22m January 2016 July 2017 / Project value / The build commenced / The duration Resurrecting the world’s oldest surviving steam-powered cotton mill, while preserving its historic 19th Century features, the Murrays’ Mills project is a £22 million innovative design-led development of a stunning Grade II* listed building. Housing 124 distinctive one, two and three bedroom apartments, the Phase One scheme, completed within 18 months, retains the historic fabric of the building, including the original stone circular staircase, amidst contemporary new build technology. The brief The focus was on sympathetically revitalising this irreplaceable heritage site and transforming it into an emerging residential area of a thriving, modern Manchester. Delivering cutting edge standards of new build development, the vision was for Murrays’ Mills to help meet the growing demand for high quality accommodation in the city. The challenges “The transformation of Murrays’ Mills is a As a Grade II* listed building, preserving the special character of this significant milestone in Ancoats’ emergence historic relic from the industrial revolution required creativity, skill and as a desirable and vibrant neighbourhood, expert care from our team throughout the design and construction it is a brilliant way to address the demand phases. Careful planning, and robust communication, with the client (Manchester Life), and the relevant local authorities, was critical to the for central accommodation in a way that successful completion of this transformative development. Located preserves and carefully evolves our former on a constrained city centre site within a ‘Conservation Area’, traffic industrial areas.” management and the phasing of works had to be carefully managed throughout the entire 18-month programme.